Selling Che: the commodification of a communist icon

Written by Jayden Glen, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Images are powerful. They can inspire fear, love and even sadness. As the common saying goes, ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’. But images can be manipulated out of their original context, and be used to enforce values against their original intention, as shown by the commercial circulation of images of Che Guevara.

Giving Context to the Iconic Image

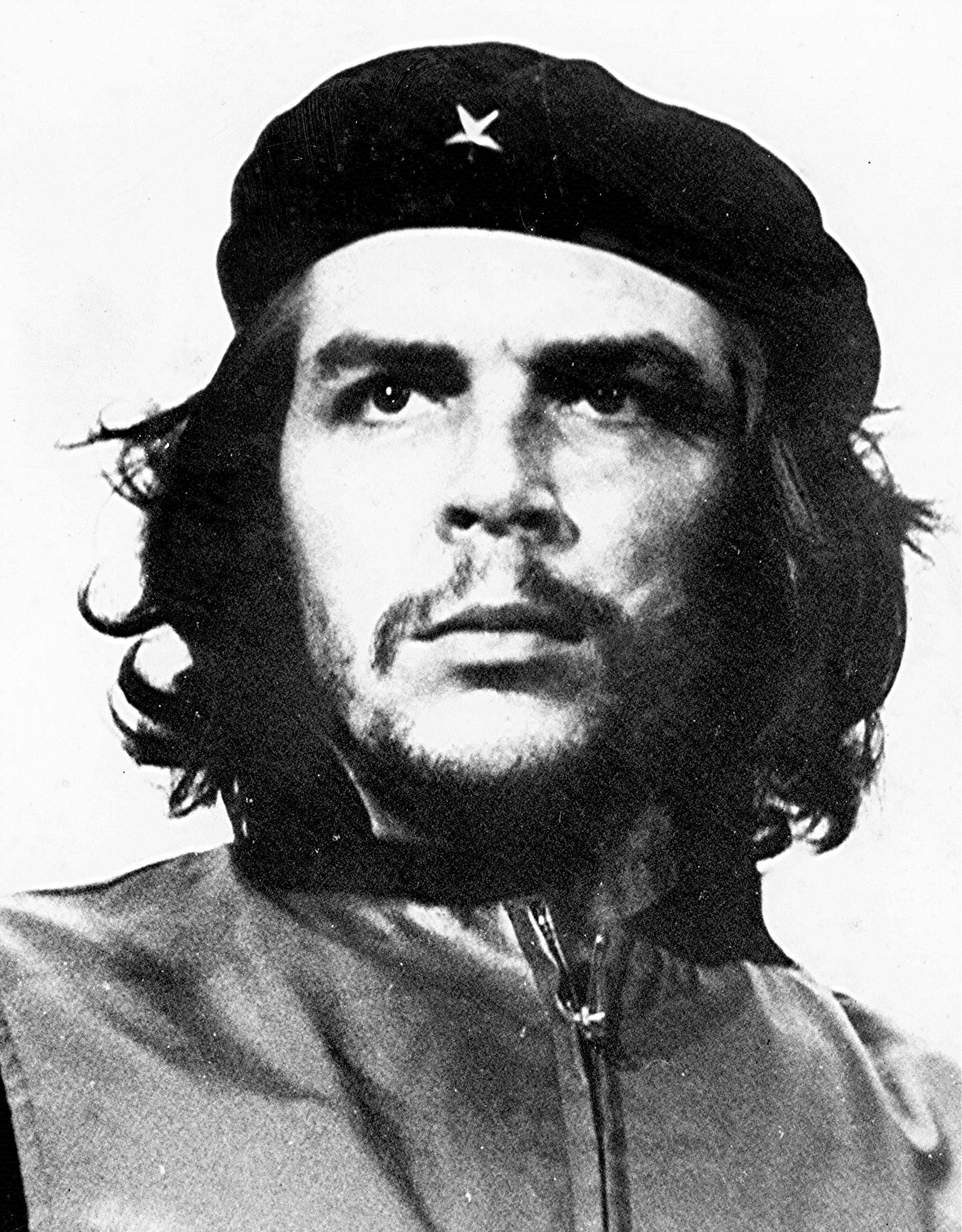

The Guerrillero Heroico or the “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter”, is an iconic photo of Che Guevara, an Argentine Marxist revolutionary from mid 1900’s Cuba.

Guevara fought for communism in Cuba, becoming a strong symbol of the revolution. He remains controversial because of the many extreme measures he took in this fight, despite being widely revered. This iconic picture of him was taken by Alberto Korda on March 5th 1960, during a funeral service for lives lost as a result of the explosion of a munitions freight boat.[1]

The photographer was, at the time, working for the Cuban newspaper Revolución. Koda explained that he was struck by Che Guevara’s powerful expression, a stare over the crowd that showed “absolute implacability”, anger and pain.[1] The newspaper never printed this photo in its coverage of the service, but Koda held on to the portrait in his own studio.[1]

It become “viral” in 1967 when Koda gave two prints to an Italian, who published it for the Cuban government. The photo then began to show up all over the world – particularly in magazines and newspaper, and then in popular culture, such as the colour poster done by Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick.[1]

Che’s later execution in October 1967 cemented his place in history, and this photo in particular would immortalize Che in popular culture too.[1] But I argue that the commercialisation of his image is itself evil, as it goes against the morals that he embodied.

The evil nature of commodifying Che

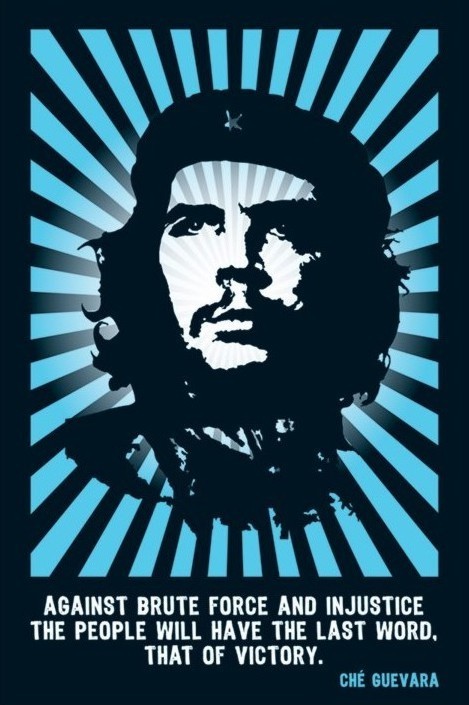

In popular culture Che Guevara’s face has become a symbol for “the power of individual expression”, reinforcing ideas of resistance to conformity and oppression.[2] These ideas resonated with many people and groups at the time, and continue to do so today. In fact, stylised as it often is into a stencil/pop-art look, as a cultural artefact the “Heroic Guerrilla Fighter” has become one of the most popular and marketable images of all time.

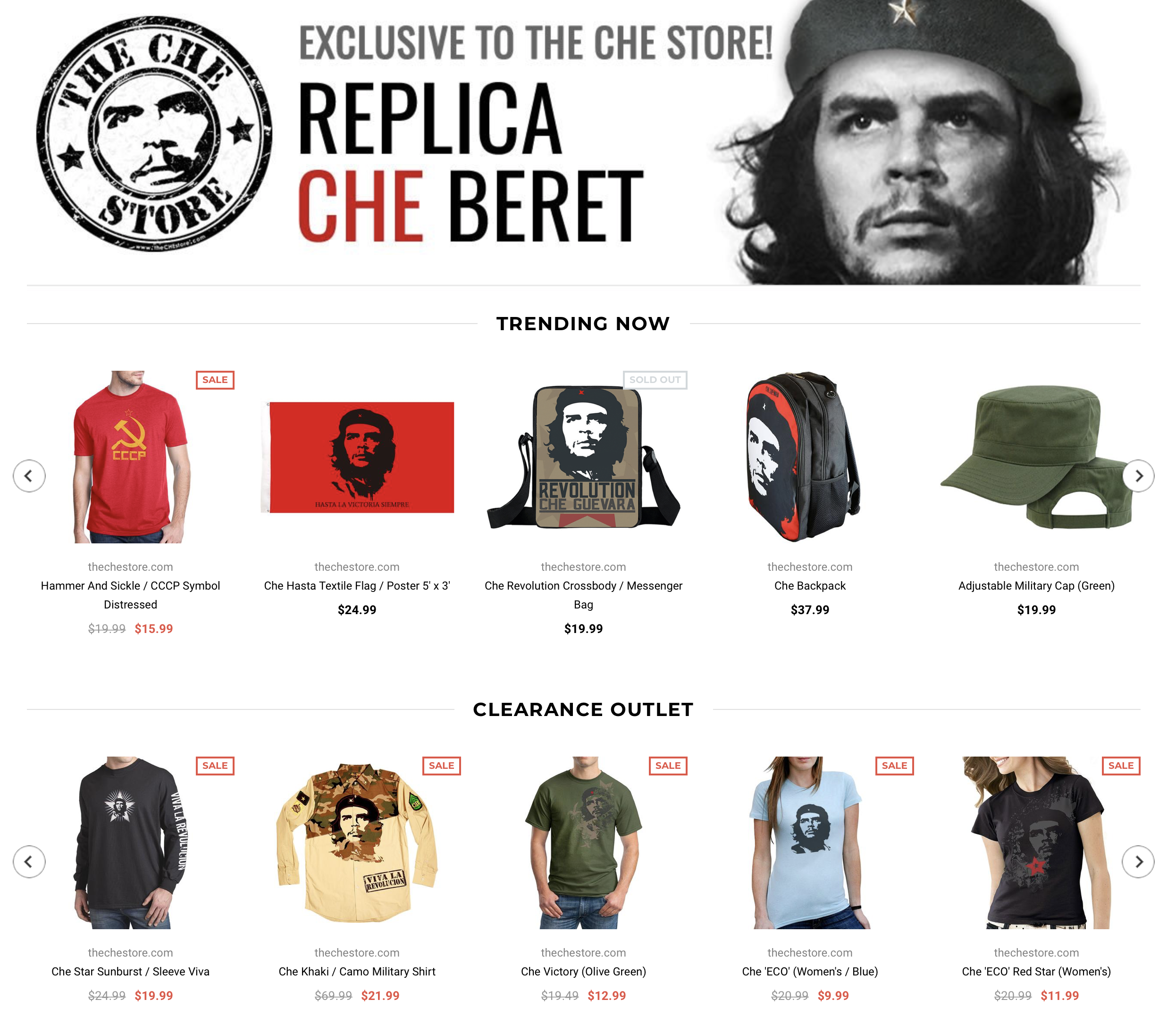

Screenshot of some of the merchandise available from www.thechestore.com, where as we can see Che Guevara’s image and other images of communism being used for profit.

Many (though not all) people may purchase these items because they share a degree of resonance with Che’s political philosophies. But the irony is that “Che would have used the royalties from any such commercial ventures to destroy the social and economic system that produced them”.[2]

The mass consumption of Che’s imagery, I believe, is reflective of what is termed “disordered capitalism”, a term used to describe how aspects of morality and politics are now intertwined with the commercial.[3] This is most observable is in the commodification of suffering, where “experiences of atrocity and abuse” have become highly profitable. This applies to the marketization of Guevara’s image primarily because his global profile occurred after his death – via execution. The significance and viral popularity, implicitly references this.

Che devoted his life to fighting against a capitalist system that in his view was significantly destroying the way of life of poorer people. As well as making money off his martyrdom to this cause, commodification of his image ignores the pain and suffering he endured through his revolutionary campaign while alive, and ignores the suffering of the people he fought for.

From an anthropological lens, this is also a case of global and local systems interacting. The image is consumed by global ‘fans’ and profited on by companies in many other countries. But the sale of his image undermines the political and ideological value that he has as a symbol to Cuban citizens in particular. The commodification of his image shows an attempt to disempower his communistic ideals.

In their analysis of suffering and its representation in media, Kleinman and Kleinman discuss suffering as “one of the existential grounds of human experience”.[3] But in a saturated media age, they argue that North American society has become de-sensitized to images of trauma.[3] Moreover many engagements with the suffering of others, via the media, are as part of a commodified system where cultural capital is gained through the presentation and circulation of trauma stories. So much so that complicated stories are reduced “to a core cultural image of victimization”.[3] Stories like Che Guevara’s become lost in an over saturation of his image, and other images of suffering – removed from context and significance, now bearing cultural and economic capital but losing moral and political potency.

A moral use of images

Frosh’s (2018) work on the way a sense of moral obligations can shape public interactions with stories and images of suffering, can help further unpack the complexities of commodifying and consuming Che Guevara’s image. In his study of Holocaust survivor testimonies, Frosh [4] reinforces that through the production and consumption of these testimonies through digital sites, individuals express and experience a “moral obligation to the past and to the dead”.

Can the same be said of Che Guevara? Should there not be a moral obligation to preserve the mindset and values of this deceased man? If so, should it be via consuming his image as a product, or by refusing to?

There are other reasons of course why this image may be rejected. Che is controversial because while he was viewed by a freedom fighter and hero by Cubans oppressed by the capitalist system of the time, he was also seen as a violent extremist and dictator: in the pursuit of revolution and freedom.

While there are many valid arguments against the man himself as, it is important to stress that even men perceived as evil can generate genuine love and admiration from people. Che is treated with and regarded as a Saint in some parts of the world due to his fight against oppressive and demeaning forces of capitalism – for example in Bolivia, where many worship him as “Saint Ernesto”, or in Cuba, where residents of Havana worship and pray to “Saint Che” by lighting a candle.[5]

As well as obligations to the dead, Frosh talks about obligations to the witness-survivor. In relation to Che Guevara, this could be examined in relation focused toward those that continue to praise and revere Che as a central part of their political ideology, and their real and personal history – in Cuba in particular, but also further afield.[4] This includes those who fought with him and for his cause, and continue to today. It includes intellectuals, workers and students.

We can apply Frosh’s idea to highlight a moral obligation to those living people connected to Che Guevara – those that remember and revere him. Including those Cubans that Che attempted to save as they were belittled and demeaned by an oppressive capitalist system. How would this additional layer of obligation be enacted, in our engagement with this image?

Concluding (and condemning)

Image retrieved from: https: //www.allposters.com/-sp/Che-Guevara-Posters_i1181_.htm accessed 8/4/19

Che Guevara was (and is) a controversial and influential figure. In examining the use of his image I have demonstrated the complexity of moral engagements with iconic political images such as this.

As a man he fought against capitalistic ideals, and has become a cultural icon. As a cultural artefact, his image on merchandise becomes a site of contention considering the moral obligations we not only have to the dead but also the living.

While debate about the evilness of Che the man remains prevalent, I conclude with the assertion that the capitalistic capture of his image for monetary gain is truly evil regardless.

References

[1] Meltzer, S. (2013). The extraordinary story behind the iconic image of Che Guevara and the photographer who took it. [online] Imaging-resource.com. Available at: https://www.imaging-resource.com/news/2013/06/06/the-extraordinary-story-behind-the-iconic-image-of-che-guevara [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].

[2] McCormick, G. (1997). Che Guevara: The Legacy of a Revolutionary Man. World Policy Journal, [online] 14(4), pp.63-79. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40209557 [Accessed 26 Mar. 2019]. [64]

[3] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996). ‘The appeal of experience; the dismay of images: Cultural appropriations of suffering in our times.’ Daedalus, 125 (1): 1–24. [8; 1; 9; 10]

[4] Frosh, P. (2016) ‘The mouse, the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response’, New media and society. Sage Publications, 20(1): 351–368 [ pg.353]

[5] Lazo, O. (2016). The Story Behind Che’s Iconic Photo. [online] Smithsonian. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/iconic-photography-che-guevara-alberto-korda-cultural-travel-180960615/ [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].