Robert Saint Clair

Peter Anstey writes…

It is not uncommon for very minor contributors to early modern thought to go unnoticed, but every now and then they turn out to be worth investigating. One such person is Robert Saint Clair. A Google search will not turn up much on Saint Clair, and yet he was a servant of Robert Boyle and a signatory to and named in Boyle’s will. He promised twice to supply the philosopher John Locke with some of Boyle’s mysterious ‘red earth’ after his master’s death, and a letter from Saint Clair to Robert Hooke was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (vol. 20, 1698, pp. 378–81).

What makes Saint Clair interesting for our purposes is his book entitled The Abyssinian Philosophy Confuted which appeared in 1697. For in that book, which contains his own translation of Bernardino Ramazzini’s treatise on the waters of Modena, Saint Clair attacks Thomas Burnet’s highly speculative theory of the formation of the earth. I quote from the epistle to the reader:

I shall not care for the displeasure of these men of Ephesus [Burnet and others], whose trade it is to make Shrines to this their Diana of Hypothetical Philosophy, I mean who in their Closets make Systems of the World, prescribe Laws of Nature, without ever consulting her by Observation and Experience, who (to use the Noble Lord Verulams words) like the Spider … spin a curious Cob-web out of their Brains … (sig. a4)

The rhetoric of experimental philosophy could hardly be more obvious. Burnet and the other ‘world-makers’ are criticized for being adherents of ‘Hypothetical Philosophy’, for making ‘Systems of the World’, and for not consulting nature by ‘Observation and Experience’. He also praises Ramazzini’s work for being ‘the most admirable piece of Natural History’ (sig. a2). Saint Clair rounds off this passage with a reference to Bacon’s famous aphorism (about which we have commented before) from the New Organon comparing the spider, the ant and the bee to current day natural philosophers (I. 95).

What can we glean from Saint Clair’s critique here? First, it provides yet another piece evidence of the ubiquity of the ESD in late seventeenth-century England: the terms of reference by which Saint Clair evaluated Burnet were clearly those of experimental versus speculative philosophy.

Second, it is worth noting the term ‘Hypothetical Philosophy’. This expression was clearly ‘in the air’ in the late 1690s in England. For instance, it is found in John Sergeant’s Solid Philosophy Asserted which was also published in 1697. Indeed, it is the very term that Newton used in a draft of his letter of 28 March 1713 to Roger Cotes to describe Leibniz and Descartes years later. Clearly the term was in use as a pejorative before Newton’s attack on Leibniz.

Saint Clair has been almost invisible to early modern scholarship on English natural philosophy and yet his case is a nice example of the value of inquiring into the plethora of minor figures surrounding those canonical thinkers who still capture most of our attention. I would be grateful for suggestions as to names of others whom I might explore.

Incidentally, Saint Clair obviously thought that John Locke might be interested in his book, for we know from Locke’s Journal that he sent him a copy.

Francis Bampfield: an early critic of experimental philosophy

Peter Anstey writes…

In a recent article Peter Harrison has drawn our attention to the phenomenon of experimental Christianity in seventeenth-century England (‘Experimental religion and experimental science in early modern England’, Intellectual History Review, 21 (2011)). In this post I would like to take up where Harrison left off and discuss one proponent of experimental religion whom Harrison does not mention, namely Francis Bampfield (1614–1684). Bampfield provides an interesting case study because while he was a promoter of experimental Christianity, he was also a harsh critic of the new experimental natural philosophy.

In two works from 1677, All in One and SABBATIKH, Bampfield lays out his case against experimental natural philosophy. In his view the source of all useful and certain knowledge is the Scriptures.

Practical Christianity, and experimental Religion is the highest Science, and the noblest Art, and the most honourable Profession, which gives light to all inferiour knowledges, and would admit into the Royalest Society, and draw nearest in resemblance and conformity, to the glorified Fellowship in the Heavenly College above, where their knowledge is perfected in visional intuitive light. Here is the prime Truth, the original Verity, as to the manifestativeness of it in legible visible ingravings, which would carry progressively into other Learning contained therein: all here is reducible to practice and use, to life and conversation; here existences and realilties are contemplated and proved, not mere Ideas and conceits speculated as elsewhere. (All in One, p. 12)

It is the mere ideas and conceits of the new experimental philosophy of the Royal Society, or the Fellows of Gresham College, that Bampfield is concerned to expose:

How many thousands have by their wandring after such misguiders left and lost their way in the dark, where their Souls have been filled with troublesome doubts, and with tormenting fears, exposing them to violent temptations of Atheism and Unbelief? and what wonder, that it is thus with the Scholar, when some of the learnedest of the Masters themselves have resolved upon this, as the conclusion of all their knowledge, that, All things are matter of doubtful questionings, and are intricated with knotty difficulties, and do pass into amazing uncertainties, and resolve into cosmical suspicions? And this, not only is the deliberate Judgement of particular Virtuoso’s in our day, but has been the publick determination of an whole University. (All in one, p. 3)

What are these ‘knotty difficulties’ that pass into ‘amazing uncertainties’ resolving into ‘cosmical suspicions’? The alert reader will no doubt see here a direct allusion to Robert Boyle’s Tracts of 1670 in which he discusses cosmical qualities that seem to have ‘such a degree of probability, as is want to be thought sufficient to Physicall Discourses’ (Works of Robert Boyle, eds Hunter and Davis, London, 1999–2000, 6, p. 303). Boyle appended to his essay on cosmical qualities another on cosmical suspicions which contains just the sort of speculative reflections that Bampfield is alluding to here. (As far as I can determine, Boyle’s is the first work in English that uses the term ‘cosmical suspicions’.) That Bampfield was a close reader of Boyle’s writings comes out in a later passage which I quote in extenso:

There is an honourable Virtuosus, who has travelled far in Natures way, and has made some of the deepest inquiries into Experimental, Corpuscular, or Mechanical Philosophy, that in the requisites of a good Hypothesis amongst others of them, doth make this to be one of its conditions, that it fairly comport not only with all other truths, but with all other Phaenomena of Nature, as well as those ’tis fram’d to explicate, and that, not only none of the Phaenomena of Nature, which are already taken notice of do contradict it at the present, but that, no Phaenomena that may be hereafter discovered, shall do it for the future. Let it therefore from hence be considered, whether seeing, that History of Nature, which is but of human indagation and compiling, is so incomplete and uncertain, and many things may be discovered in after-times by industry, or in some other way by providential dispensing, which are not now so much as dreamed of, and which may yet overthrow Doctrines speciously enough accommodated to the Observations, that have been hitherto made (as is by himself fore-seen and acknowledged) whether now, the only prevention and remedy in this case (which is otherwise so full of just fears, of real doubts, of endless dissatisfaction, and of perplexing difficulties) be not, to bring all sorts of necessary knowledges to the Pan-sophie, the Alness of Wisdom, in the Scriptures of Truth, where none of the forementioned Scriptures have any ground to set their foot on, in regard that Word-Revelations about Natures Secrets, are the unerring products of infinite Wisdom, and of universal fore seeingness, which are always uniform and the same, in their well-established order, and stated ordinary course without any variation, by an unchangeable Law of the All-knowing Truthful Creator, and Governour, and Redeemer. (All in One, pp. 56-7)

Bampfield is, of course, referring to Boyle’s Excellency of Theology (Works, 8, p. 89) and while he is cautious not to be overtly critical of Boyle here, the thrust of his comments is to undermine the epistemic status of the experimental philosophy, calling it ‘incomplete and uncertain’. For, as he says in his sequel SABBATIKH:

the unscriptural way they take in their researches into natural Histories and experimental Philosophy, will never so attain its useful end for the true advance of profitable Learning, till more studied in the Book of Scriptures, and suiting all experiments unto this word-knowledge. (SABBATIKH, p. 53)

It is ‘word knowledge’ and not knowledge of the world that Bampfield is defending. What Boyle himself made of all of this, if it even came to his attention, we will never know. He never mentions Bampfield in any of his works or correspondence.

Teaching Experimental Philosophy: Desaguliers and Boyle

Peter Anstey writes…

According to ECCO there were one hundred books published in the eighteenth century with the term ‘experimental philosophy’ in their title. What is surprising about these books is that the majority of them are courses in or lectures on experimental philosophy: they are pedagogical works rather than works in natural philosophy per se.

According to ECCO there were one hundred books published in the eighteenth century with the term ‘experimental philosophy’ in their title. What is surprising about these books is that the majority of them are courses in or lectures on experimental philosophy: they are pedagogical works rather than works in natural philosophy per se.

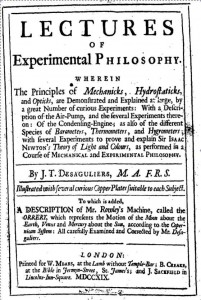

One of the earliest of these works was Lectures of Experimental Philosophy by John Theophilus Desaguliers published in 1719. This work gives the principles of mechanics, hydrostatics and optics, explaining them with descriptions of experiments that had recently been used in these disciplines.

The work is written in the spirit of the experimental philosophy and before Desaguliers launches into his exposition of mechanics, the first discipline that he discusses, he provides the reader with a sketch of the ‘principles’ of natural philosophy. What is interesting is that much of this derives without acknowledgment from Robert Boyle’s Origin of Forms and Qualities (1666/7). Thus, Desaguliers tells us that:

- 1. That the Matter of Natural Bodies is the same; namely, a Substance extended, divisible, and impenetrable. (p. 7)

In Forms and Qualities Boyle says,

- The Matter of all Natural Bodies is the Same, namely a Substance extended and impenetrable. (Works of Robert Boyle, eds Hunter & Davis, 5: 333)

If one were to quibble that Desaguliers has left out the word ‘divisible’, we need only to turn to an earlier passage in Forms and Qualities where Boyle says:

- there is one catholic or universal matter common to all bodies, by which I mean a substance extended, divisible, and impenetrable. (Works, 5: 305)

That Desaguliers read this passage is evident from his third claim:

- 3. That Local Motion is the chief Principle amongst second Causes, and the chief Agent of all that happens in Nature. (p. 8)

Boyle says in the very next paragraph,

- that Local Motion seems to be indeed the Principl amongst Second Causes, and the Grand Agent of all that happens in Nature. (Works, 5: 306)

There are other borrowings from Forms and Qualities, but space prevents me from listing them here. Two points are worth noting, however. First, it is very interesting to see concrete evidence of the influence of Boyle’s Forms and Qualities in the latter years of the second decade of the eighteenth century. Until now there has been little recognition of the impact of this specific work by Boyle, though few would doubt his enormous impact on British experimental philosophy in general.

Second, the text that Desaguliers lifts from Boyle appears in the speculative part of Forms and Qualities: it is speculative natural philosophy and is supported in the ‘historical part’ of that work by experimental observations. There is no sense of this division in Desaguliers’ treatment of these ‘principles’, though he does bring some experimental evidence to bear against the Cartesian materia subtilis. After dismissing various other speculative theories, such as Aristotelianism, Desaguliers simply introduces Boyle’s speculative theory with the following words:

- That Philosophy therefore is the most reasonable, which teaches …

Early modern x-phi: a genre free zone

Peter Anstey writes…

One feature of early modern experimental philosophy that has been brought home to us as we have prepared the exhibition entitled ‘Experimental Philosophy: Old and New’ (soon to appear online) is the broad range of disciplinary domains in which the experimental philosophy was applied in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some of the works on display are books from what we now call the history of science, some are works in the history of medicine, some are works of literature, others are works in moral philosophy, and yet they all have the unifying thread of being related in some way to the experimental philosophy.

Two lessons can be drawn from this. First – and this is a simple point that may not be immediately obvious – there is no distinct genre of experimental philosophical writing. Senac’s Treatise on the Structure of the Heart is just as much a work of experimental philosophy as Newton’s Principia or Hume’s Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals. To be sure, if one turns to the works from the 1660s to the 1690s written after the method of Baconian natural history, one can find a fairly well-defined genre. But, as we have already argued on this blog, this approach to the experimental philosophy was short-lived and by no means exhausts the works from those decades that employed the new experimental method.

Second, disciplinary boundaries in the 17th and 18th centuries were quite different from those of today. The experimental philosophy emerged in natural philosophy in the 1650s and early 1660s and was quickly applied to medicine, which was widely regarded as continuous with natural philosophy. By the 1670s it was being applied to the study of the understanding in France by Jean-Baptiste du Hamel and later by John Locke. Then from the 1720s and ’30s it began to be applied in moral philosophy and aesthetics. But the salient point here is that in the early modern period there was no clear demarcation between natural philosophy and philosophy as there is today between science and philosophy. Thus Robert Boyle was called ‘the English Philosopher’ and yet today he is remembered as a great scientist. This is one of the most important differences between early modern x-phi and the contemporary phenomenon: early modern x-phi was endorsed and applied across a broad range of disciplines, whereas contemporary x-phi is a methodological stance within philosophy itself.

What is it then that makes an early modern book a work of experimental philosophy? There are at least three qualities each of which is sufficient to qualify a book as a work of experimental philosophy:

- an explicit endorsement of the experimental philosophy and its salient doctrines (such as an emphasis on the acquisition of knowledge by observation and experiment, opposition to speculative philosophy);

- an explicit application of the general method of the experimental philosophy;

- acknowledgment by others that a book is a work of experimental philosophy.

Now, some of the books in the exhibition are precursors to the emergence of the experimental philosophy (such as Bacon’s Sylva sylvarum). Some of them are comments on the experimental philosophy by sympathetic observers (Sprat’s History of the Royal Society), and others poke fun at the new experimental approach (Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels). But this still leaves a large number of very diverse works, which qualify as works of experimental philosophy. Early modern x-phi is a genre free zone.

Who invented the Experimental Philosophy?

Peter Anstey writes…

Sometimes the question ‘Who invented X?’ has no determinate answer, in spite of claims of particular individuals. One thinks of questions like ‘Who invented the internet?’ and the various dubious claims to this honour. Christoph Lüthy has argued quite convincingly that ‘the microscope was never invented’ (Early Science and Medicine, 1, 1996, p. 2). I suggest that the same probably goes for the experimental philosophy: there is no single person or group of people who created it, rather it somehow ‘emerged’ in Europe sometime between the death of Francis Bacon in 1626 and the founding of the Royal Society in 1660. One place to look for answers is to trace the early uses of the term ‘experimental philosophy’.

Here is the evidence that I am aware of for the emergence of the term ‘experimental philosophy’ in early modern England. The first English work to use the term ‘experimental philosophy’ according to EEBO was Robert Boyle’s Spring of the Air in 1660. Interestingly, the term philosophia experimentalis had already appeared in the title of Nicola Cabeo’s Latin commentary on Aristotle’s Meteorology of 1646 and Boyle cites Cabeo’s book twice in Spring of the Air. The first English book to use the term in its title was Abraham Cowley’s A Proposition for the Advancement of Experimental Philosophy of 1661. From then on, however, books about experimental philosophy start to roll off the presses of England. Boyle’s Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy and Henry Power’s Experimental Philosophy, both published in 1663, got the ball rolling. (Incidentally, Cabeo’s book was reprinted in Rome in 1686 under the title Philosophia experimentalis.) As for manuscript sources, the earliest use of the term ‘experimental philosophy’ that I have found is in Samuel Hartlib’s Ephemerides in 1635.

Another place to look for evidence for the inventor of the experimental philosophy is in discussions of natural philosophy and of experiment. It appears that Francis Bacon never used the term ‘experimental philosophy’, but he did develop a conception of experientia literata (learned experience), which might be thought to be a precursor of the experimental philosophy. This appears in Book 5 of his De augmentis scientiarum of 1623, where it is distinguished from interpretatio naturae (interpretation of nature). The experientia literata is a method of discovery proceeding from one experiment to another, whereas interpretatio naturae involves the transition from experiments to theory. But this doesn’t resemble the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy very closely. For example, the experimental philosophy was, on the whole, opposed to speculation and hypotheses and there is no sense of opposition or tension in Bacon’s distinction.

Furthermore, a distinction between operative (or practical) and speculative philosophy was commonplace in scholastic divisions of knowledge in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, and this, no doubt provided the basic dichotomy on which the experimental/speculative distinction was based. But the operative/speculative distinction doesn’t map very well onto the experimental/speculative distinction, not least because by ‘operative sciences’ the scholastics meant ethics, politics and oeconomy (that is, management of society) and not observation and experiment.

Who invented the experimental philosophy? I don’t think that there is a determinate answer to this question, but I’m happy to be corrected and am keen for suggestions as to where to look for more evidence.

Locke’s Master-Builders were Experimental Philosophers

Peter Anstey says…

In one of the great statements of philosophical humility the English philosopher John Locke characterised his aims for the Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690) in the following terms:

- The Commonwealth of Learning, is not at this time without Master-Builders, whose mighty Designs, in advancing the Sciences, will leave lasting Monuments to the Admiration of Posterity; But every one must not hope to be a Boyle, or a Sydenham; and in an age that produces such Masters, as the Great – Huygenius, and the incomparable Mr. Newton, with some other of that Strain; ’tis Ambition enough to be employed as an Under-Labourer in clearing Ground a little, and removing some of the Rubbish, that lies in the way to Knowledge (Essay, ‘Epistle to the Reader’).

Locke regarded his project as the work of an under-labourer, sweeping away rubbish so that the ‘big guns’ could continue their work. But what is it that unites Boyle, Sydenham, Huygens and Newton as Master-Builders? It can’t be the fact that they are all British, because Huygens was Dutch. It can’t be the fact that they were all friends of Locke, for when Locke penned these words he almost certainly had not even met Isaac Newton. Nor can it be the fact that they were all eminent natural philosophers, after all, Thomas Sydenham was a physician.

In my book John Locke and Natural Philosophy, I contend that what they had in common was that they all were proponents or practitioners of the new experimental philosophy and that it was this that led Locke to group them together. In the case of Boyle, the situation is straightforward: he was the experimental philosopher par excellence. In the case of Newton, Locke had recently reviewed his Principia and mentions this ‘incomparable book’, endorsing its method in later editions of the Essay itself. Interestingly, in his review Locke focuses on Newton’s arguments against Descartes’ vortex theory of planetary motions, which had come to be regarded as an archetypal form of speculative philosophy.

In the case of Huygens, little is known of his relations with Locke, but he was a promoter of the method of natural history and he remained the leading experimental natural philosopher in the Parisian Académie. In the case of Sydenham, it was his methodology that Locke admired and, especially those features of his method that were characteristic of the experimental philosophy. Here is what Locke says of Sydenham’s method to Thomas Molyneux:

- I hope the age has many who will follow [Sydenham’s] example, and by the way of accurate practical observation, as he has so happily begun, enlarge the history of diseases, and improve the art of physick, and not by speculative hypotheses fill the world with useless, tho’ pleasing visions (1 Nov. 1692, Correspondence, 4, p. 563).

Note the references to ‘accurate practical observation’, the decrying of ‘speculative hypotheses’ and the endorsement of the natural ‘history of diseases’ – all leading doctrines of the experimental philosophy in the late seventeenth century. So, even though Sydenham was a physician, he could still practise medicine according to the new method of the experimental philosophy. In fact, many in Locke’s day regarded natural philosophy and medicine as forming a seamless whole in so far as they shared a common method. It should be hardly surprising to find that Locke held this view, for he too was a physician.

If it is this common methodology that unites Locke’s four heroes then we are entitled to say ‘Locke’s Master-Builders were experimental philosophers’. I challenge readers to come up with a better explanation of Locke’s choice of these four Master-Builders.