Peter Anstey writes …

There were many critics of experimental philosophy in its early years. On this blog we have discussed the criticisms of Margaret Cavendish and Francis Bampfield, both of whom were English, and G. W. Leibniz, who was German. In this post we examine the views of the French philosopher Nicolas Malebranche who was highly critical of experimental philosophy too.

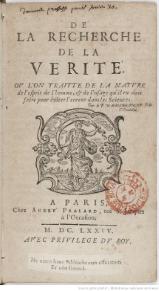

In the first edition of his The Search After Truth of 1674, Malebranche devotes the last section of Book Two to ‘Those who perform experiments’, and this section appears in all six subsequent editions of the book. (See The Search After Truth, eds T. M. Lennon and P. J. Olscamp, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997, pp. 159–60.)

He opens his treatment of the subject with some general comments that apply both to chemists and ‘all those who spend their time performing experiments’. Ostensibly, the criticisms are not directed at experimental philosophy per se, but towards experimental philosophers themselves. ‘Do not blame experimental philosophy [philosophie expérimentale]’, says Malebranche; it is the errors of its practitioners that he castigates.

He then proceeds to list seven faults, though ‘there are still many other defects … we do not pretend to cover them all here’ (p. 160).

First, their experiments are normally directed by chance and not by reason.

Second, they are ‘preoccupied with curious and unusual experiments’ rather than beginning with the simplest and building up from there.

Third, they seek out those experiments that will bring them profit, lucriferous experiments, as Bacon would call them.

Fourth, they don’t take enough care to note down ‘all the particular circumstances’ that pertain to the experiment at hand, the time of day, place, quality of the materials, etc.

Fifth, they draw too many conclusions from a single experiment, whereas it’s normally the case that one conclusion can only be drawn from many experiments.

Sixth, they only consider particular effects without ascending to ‘primary notions of things that compose bodies’ (p. 159).

And seventh, they often ‘lack courage and endurance, and give up because of fatigue or expense’ (p. 160).

None of these criticisms seem very serious, after all, it is easy to find exceptions to each one in the experimental practice of experimental philosophers in the 1660s and 1670s. One could hardly accuse Newton’s of being directed by chance in the construction of his experimentum crucis for establishing the heterogeneity of white light, even if his discovery of the oblong form of the spectrum of colours in his first experiment was unexpected or discovered by chance. Nor could one accuse Boyle of giving up on account of fatigue or expense in his air-pump experiments.

Yet the heart of Malebranche’s critique is found in the final paragraph of the section on the causes of the seven defects. He lists three causes: lack of application, misuse of the imagination, and, most importantly, judging the differences and changes among bodies only by sensation (p. 160).

This third cause is Malebranche’s real reservation about, not experimental philosophers, but experimental philosophy itself: for this cause implies an over-reliance on the senses, and by implication, an under-utilisation of reason, and, in particular, reasoning from clear and distinct ideas. The whole of Book One of The Search After Truth is given over to a discussion of the unreliability of the senses. For example, one rule of thumb that he sets out in Chapter 5 is: ‘Never judge by means of the senses as to what things are in themselves …’ (p. 24).

Of course, Malebranche is not averse to appealing to experiments and observations when they reinforce a point he is making (see Book I, chap. 12, pp. 56–7), however, the prioritising of experiment and observation above reasoning from pre-established principles and hypotheses – a central tenet of experimental philosophy – is not one of his epistemic values. Malebranche was opposed to experimental philosophy in principle, and not merely because of the ‘defects’ of its practitioners.