Testimony and evidence from the scriptures

Juan Gomez writes…

For those familiar with the rhetoric and methodology of Early Modern Experimental Philosophy (the faithful readers of this blog among them) it is no surprise that the emphasis on facts, observation, and experiment as the only solid grounds of knowledge was highlighted in almost every published text by the promoters of the experimental method. Within natural philosophy, the relevant facts and experiments were confined to nature and its workings. However, pinpointing the relevant facts and observations for knowledge in areas outside of natural philosophy was a more delicate matter. As we have argued for in this blog, the methodology of Early Modern Experimental Philosophy was adopted by many eighteenth-century figures in areas traditionally contained under moral philosophy, such as ethics, aesthetics, and theology. But which sort of facts and observations entitled them to apply the same methodology that had contributed so much to the progress of mankind and our knowledge of the natural world?

George Turnbull (the philosopher, teacher, and theologian who has many times been the subject of our posts) thought that introspection could give us access to facts about the anatomy of our mind, and that paintings provided in moral philosophy the same role experiments did in natural. But what about facts and observations regarding religious thought? A couple of years ago I commented on Turnbull’s ‘experimental theism.’ We saw how Turnbull argued that the miracles performed by Jesus Christ serve as the samples and experiments that prove that he truly was the son of God and possessed knowledge of a more perfect stage in nature. However, the only evidence we have of those miracles is found in the gospels of the apostles, so why is it that those accounts of miracles count as proper evidence? David Hume’s rejection of miracles was based precisely on the claim that evidence from testimony would never be stronger than evidence from experience, and so belief in miracles from testimony of them is not justified. Turnbull, on the other hand, believed that the testimony given in the gospels was in fact enough evidence, and it is his argument that I want to focus on for the rest of today’s post.

In the conclusion to his Principles of Christian Philosophy (1749) Turnbull claims that he will show that “the christian revelation gives a very proper, full, and truly philosophical evidence for the truth of that doctrine concerning God, providence, virtue, and a future state. As I mentioned earlier, Jesus and his apostles had a first hand access to the evidence, i.e. the works and miracles of Jesus Christ. But what we have access to is testimony of that evidence, and not the evidence itself. This being the case, we must wonder if testimony is reliable enough. In an earlier section of his book, Turnbull argues that testimony, whether of the senses, or of introspection, or of whatever kind, must be examined under the same criteria:

- “[E]xperiences taken upon testimony, must all of them, whether concerning objects of the outward senses, or inward sentiments, operations, and affections of the mind, be tried, examined, and admitted, or repelled by the very same criteria, or rules of moral evidence.”

So the testimony from the gospels should be examined the same way we examine any testimony of experiments in natural philosophy. Turnbull then claims that we have no reason to doubt the testimony whether of Jesus or the apostles, just as we wouldn’t doubt the testimony of a skilled scientist:

- “For surely, one who had admitted the truth of a proposition in geometry, or of an experiment in natural philosophy, upon the testimony of one skill’d in these arts, in whom he had reason to confide, has no ground to doubt such testimony, when having made further advances in geometry or experimental philosophy, he comes to see the truths he had formerly received upon testimony, as it were, with his own eyes. And must not the same hold true with respect to moral truths?”

It seems that Turnbull does not confront the issue of the reliability of testimony as proper evidence. Of course, he could argue that we do not have any reason to doubt the account given by the apostles because they are characterized as having a virtuous moral character, and so is Jesus. But these accounts come from the gospels themselves, so unless we have an external account of the moral character of those giving the testimony, it seems that we might have grounds to doubt them.

Turnbull, however, seems to think that this is not an issue and that in fact “the enemies of Christianity have in no age ever attacked the evidence” for the history of Jesus Christ. In particular, Turnbull argues that the main reason to accept the evidence from testimony is the fact that it is not inconsistent with the knowledge we gain from our observation of the natural world. The main purpose of Turnbull’s text is to show that revealed religion confirms the knowledge accessed from natural religion, and it is in this sense that the former is useful. So as long as testimony agrees with experience, there is no reason to reject it.

- “Surely it cannot be said, that because one kind of evidence for a truth is good, that therefore another kind of evidence is not good. And therefore the evidence in such a case must stand thus. ‘Here is a double evidence for certain truths; an evidence from the nature of things; an intrinsick evidence; and likewise an extrinsick evidence, or an evidence from testimony, upon which there is a sufficient reason to rely independently of all other considerations.'”

It appears then that the testimony of the gospels is just a different kind of evidence for the Christian doctrines, and since it confirms the claims we have deduced from our experience of the world, then such testimony is reliable. Turnbull can only claim that testimony is reliable after proving the doctrines from natural religion, i.e. by examining the world and the workings of our mind. So Turnbull’s strategy is not to argue for the reliability of testimony itself, but rather to claim that since it is not inconsistent with what we have learnt from experience, then there is no reason to reject it.

The demise of Spinozism and the rise of Dutch experimental philosophy

A guest post by Wiep van Bunge.

Wiep van Bunge writes…

Rienk Vermij has demonstrated quite convincingly that the first Dutch Newtonians were actively engaged in countering the threat Spinoza posed (Vermij 2003). A crucial moment in the simultaneous demise of Spinozism and the rise of experimental philosophy was Bernard Nieuwentijt’s publication, in 1715, of his famous Het regt gebruik der wereldbeschouwingen – translated into English, French and German. Nieuwentijt specifically marked out Spinoza’s atheism as his main target, inspiring many dozens of countrymen and many others abroad to discern the providential reign of a supernatural Creator, who was not to be identified with Nature in the way the Spinozists had been doing for several decades.

More interesting, however, is his posthumous Gronden van zekerheid, in which he further developed a number of comments on mathematics made by one of Spinoza’s earliest critics, the linguist and philosopher Adriaen Verwer in his 1683 refutation of Spinoza’s Ethics. Verwer had warned his readers against Spinoza’s confusion of entia realia, things that really exist, and entia rationis, things we can talk about coherently but which are only supposed to exist even though we are able to conceive of them clearly and distinctly. Spinoza’s fundamental error, according to Verwer, consisted in supposing that once a clear and distinct idea has been formed, the ideatum conceived of in the idea really exists (Verwer 1683; 1–5).

In Gronden van zekerheid Nieuwentijt first elaborates on the distinction between ‘imaginary’ (denkbeeldige) and ‘realistic’ (zakelijke) mathematics, that is between a mathematics concerned with abstract notions without any corresponding objects in reality, and a mathematics concerned with objects the reality of which has been established by experience. Thus Nieuwentijt attempts to ensure that the use of mathematical reasoning is reserved for the behaviour of natural, observable objects. After having demonstrated the benefits of a ‘realistic’ use of mathematics, Nieuwentijt in the fourth part of Gronden van zekerheid accuses Spinoza of being merely an ‘imaginary’ mathematician, who just made it look as if his abstract metaphysics had anything to do with the real world. In reality, or so Nieuwentijt felt, Spinoza was only talking about his own, private ideas. What is worse, Spinoza consciously refused to acknowledge the need to ascertain the correspondence of these ideas to any external reality, as is evident, Nieuwentijt continued, from Spinoza’s conception of truth. Neither was he prepared to check the truth of his ‘deductions’ against any empirical evidence, which led him to preposterous conclusions, such as regarding the human intellect as being a part of God’s infinite intellect as well as an idea of an existing body (Nieuwentijt 1720: 244ff).

Throughout Gronden van zekerheid Nieuwentijt points to the obvious alternative to Spinoza’s ‘figments of the imagination’: the experiential ‘realistic mathematics’ adopted by the Royal academies of Britain, France and Prussia as well as by countless serious scientists across Europe. Philosophy, Nieuwentijt contended in the fifth and final part of his book, should become a ‘realistic metaphysics’ (sakelyke overnatuurkunde), which rests on the same foundations that realistic mathematicians build on: faith in the revealed Word of God and experience, to which he adds that philosophers are often best advised to suspend judgment because we simply lack the data necessary for answering many of the question traditionally raised by metaphysicians (Nieuwentijt 1720: 388ff). Newton, ‘the mathematical Knight’, had shown the way by setting up experiments in order to confirm the truth of conclusions arrived at by means of deduction and by making sure that the general principles from which these conclusions derived were the result of ‘empirical’ induction (Nieuwentijt 1720: 83–84; 188 ff). In addition, Nieuwentijt was happy to confirm that Newton’s work clearly established the providential reign of the Creator over His creation, making it an ideal weapon in the fight against atheism (Nieuwentijt 1720: 228).

It would seem, then, that in Nieuwentijt’s eyes, and Verwer appears to have been of the same opinion, Spinozism was actually a philosophical instance of ‘enthusiasm’ – not unlike the German theologian Buddeus’ earlier suggestion (Buddeus 1701: 15–16). Both were appalled to read that according to Spinoza ideas were true to the extent that he himself felt them to be true, instead of checking their correspondence to the world as we know it. Thus Nieuwentijt continued an Aristotelian and humanist tradition according to which ‘contemplative philosophy’ represented a type of ‘philosophical enthusiasm’ (Heyd 1995: Ch. 4).

Buddaeus, I.F., Dissertatio philosophica de Spinozismo ante Spinozam (Halle, 1701).

Heyd, Michael, ‘Be Sober and Reasonable’. The Critique of Enthusiasm in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries (Leiden, 1995).

Nieuwentijt, Bernard, Het regt gebruik der wereldtbeschouwingen, ter overtuiginge van ongodisten en en ongelovigen aangetoont (Amsterdam,1715).

–, Gronden van zekerheid, of de regte betoogwyse der wiskundigen, So in het denkbeeldige als in het het zakelyke (Amsterdam, 1720).

Vermij, Rienk, ‘The Formation of the Newtonian Natural Philosophy. The Case of the Amsterdam Mathematical Amateurs’, The British Journal for the History of Science 36 (2003), 183–200.

Verwer, Adriaen,’t Mom-Aensicht der atheisterij afgerukt door een verhandeling van den aengeboren stand der menschen (Amsterdam, 1683).

Understanding Newton’s Experiments as Instances of Special Power

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In my last few posts, I have been discussing the nature of observations and experiments in Newton’s Opticks. In my first post on this topic, I argued that Newton’s distinction between observation and experiment turns on their function. That is, the experiments introduced in book 1 offered individual, and crucial, support for particular propositions, whereas the observations introduced in books 2 and 3 only supported propositions collectively. In my next post, I discussed the observations in more detail, arguing that they resemble Bacon’s ‘experientia literata’, the method by which natural histories were supposed to be generated. At the end of that post, I suggested that, in contrast to the observations, Newton’s experiments look like Bacon’s ‘instances of special power’, which are particularly illuminating cases introduced to provide support for specific propositions. Today I’ll develop this idea.

Note, before we continue, that there are two issues here that can be treated independently of one another. One is establishing the extent of Bacon’s historical influence on Newton; the other is establishing the extent to which Bacon’s methodology can illuminate Newton’s. In this post I am doing the latter – using Bacon’s view only as an interpretive tool.

Identifying ‘instances of special power’ (ISPs) was an important step in the construction of a Baconian natural history. ISPs were experiments, procedures, and instruments that were held to be particularly informative or illuminative. These served a variety of purposes. Some functioned as ‘core experiments’, introduced at the very beginning of a natural history, and serving as the basis for further experiments. Others played a role later in the process. They included experiments that were supposed to be especially representative of a certain class of experiments, tools and experimental procedures that provided interesting shortcuts in the investigation, and model examples that came very close to providing theoretical generalisations. In some cases, a collection of ISPs constituted a natural history.

The following features were typical of ISPs. Firstly, they were considered to be particularly illuminating experiments, procedures or tools. For example, a crucial instance, or a particularly clear or informative experiment, or experimental procedure. Secondly, they were supposed to be replicated. On Bacon’s view, replication was not merely an exercise for verifying evidence; it was an exercise for the mind, ensuring that one had truly grasped the phenomenon. Thirdly, they were versatile, in that they could be used in several different ways. As we shall see, the experiments of book 1 display these essential features.

In book 1 of the Opticks, Newton employed a method of ‘proof by experiments’ to support his propositions. Each experiment was introduced to reveal a specific property of light, which in turn proved a particular proposition. We know that Newton conducted many experiments in his optical investigations, so why did he present the experiments as he did, when he did? When we consider Newton’s experiments alongside Bacon’s instances of special power, common features start to emerge.

Firstly, for each proposition he asserted, Newton introduced a small selection of experiments in support – those that he considered to be particularly illuminating or, in his own words, “necessary to the Argument”. Unlike in his first paper, in the Opticks, Newton did not label any experiments ‘experimentum crucis’. But his use of terms such as ‘necessary’ and ‘proof’ make it clear that these experiments were supposed to provide strong support: just like ISPs.

Secondly, Newton usually provided more than one experiment to support each proposition. These were listed in order of increasing complexity and were carefully described and illustrated. That Newton took this approach, as opposed to just reporting on their results, suggests that these experiments were supposed to be an exercise for the reader: they were about more than just proof or confirmation of the proposition. The reader was supposed either to be able to replicate the experiment, or at least to understand its replicability. Starting with the simplest experiment, Newton led his reader by the hand through the relevant properties of light, to ensure that they were properly grasped. Like Bacon’s ISPs, then, Newton’s experiments were intended to be replicated.

Thirdly, Newton’s experiments were recycled in a variety of roles in the Opticks. For example, the experiments he used to support proposition 2 part II were experiments 12 and 14 from part I. Newton introduced and developed these experiments in several different contexts to illuminate and support different propositions. Again, this is typical of Bacon’s ISPs.

And so, Newton’s experiments in the Opticks play a role analogous to Bacon’s instances of special power, and thinking of them as such explains why they are presented as they are. They are particularly illuminating cases that are introduced to provide support for specific propositions. Newton selected the experiments which best functioned as ISPs for inclusion in the Opticks. Moreover, seen in this light, the seemingly disparate set of experiments start to look like a far more cohesive collection, or a natural history.

Many commentators have emphasised the ways that Newton deviated from Baconian method. Through this sequence of posts, I have argued that the Opticks provides a striking example of conformity to the Baconian method of natural history.

Margaret Cavendish: speculative philosopher

Peter Anstey writes …

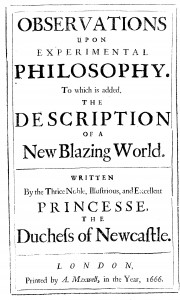

Two years ago on this blog I addressed the ‘Straw Man Problem‘ for the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy. The apparent problem, according to some critics of the ESD, is that there were no speculative philosophers in the early modern period. In my response to that problem I listed The Duchess of Newcastle, Margaret Cavendish, as one of the few advocates of speculative philosophy in seventeenth-century England and in this post I want to explore her views in a little more depth.

Cavendish wrote the most sustained critique of experimental philosophy in the seventeenth century. Her Observations upon Experimental Philosophy, comprising 318 pages, was first published in 1666 and went into a second edition in 1668. In this work Cavendish gives a critical reading of many works of the new experimental philosophy in order to justify her own speculative natural philosophy. Within her sights are Robert Boyle’s Sceptical Chymist (1661), Henry Power’s Experimental Philosophy (1664) and Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665).

It is interesting to compare Cavendish’s views in this work with those of the young Robert Boyle a decade earlier. As I pointed out in my last post, in his ‘Of Naturall Philosophie’ of c. 1654, Boyle claims that there are two principles of natural philosophy, the senses and reason. He plumps for the senses. Cavendish in her Observations acquiesces in the very same principles, but takes the opposing line: for her, reason trumps the senses.

It is interesting to compare Cavendish’s views in this work with those of the young Robert Boyle a decade earlier. As I pointed out in my last post, in his ‘Of Naturall Philosophie’ of c. 1654, Boyle claims that there are two principles of natural philosophy, the senses and reason. He plumps for the senses. Cavendish in her Observations acquiesces in the very same principles, but takes the opposing line: for her, reason trumps the senses.

What is important for our interests here is not only the direct contrast with Boyle’s embryonic experimental philosophy, but the manner in which, for Cavendish, the terms of reference for the choice are between experimental and speculative philosophy. The following extracts give a feel for her position:

I say, that sense, which is more apt to be deluded than reason, cannot be the ground of reason, no more than art can be the ground of nature: … For how can a fool order his understanding by art, if nature has made it defective? or, how can a wise man trust his senses, if either the objects be not truly presented according to their natural figure and shape, or if the senses be defective, either through age, sickness, or other accidents … And hence I conclude, that experimental and mechanic philosophy cannot be above the speculative part, by reason most experiments have their rise from the speculative, so that the artist or mechanic is but a servant to the student. (Cavendish, Observations, ed. O’Neill (Cambridge), p. 49, emphasis added)

experimental philosophy has but a brittle, inconstant, and uncertain ground. And these artificial instruments, as microscopes, telescopes, and the like, which are now so highly applauded, who knows but they may within a short time have the same fate; and upon a better and more rational enquiry, be found deluders, rather than true informers (ibid., p. 99)

And toward the end of a long discussion of chemistry and chemical principles she reiterates her conclusion:

if reason be above sense, then speculative philosophy ought to be preferred before the experimental, because there can no reason be given for anything without it (ibid., p. 241)

Cavendish’s Observations first appeared at a very sensitive time for the Royal Society, for it had been the subject of much criticism from without and was in the process of securing an apologetical History of the Royal-Society by Thomas Sprat.

Now, there is no doubt that some of the more prominent Fellows of the Society are in view in her critique. Yet, it is important that we do not over-extend the target of the Observations, for, it is very much aimed at experimental philosophy and hardly makes reference to the Royal Society at all. Within a year of its publication the Duchess was to make a famous visit to the Society and the correspondence that ensued does not suggest that Henry Oldenburg and others regarded her as a hostile critic of the Society. This reinforces the view that her focus was more specific, namely, experimental philosophy.

Interestingly, after Cavendish’s death the following lines appeared in A Collection of Letters and Poems (London, 1678) written in her honour:

Philosophers must wander in the dark;

Now they of Truth can find no certain mark;

Since She their surest Guide is gone away,

They cannot chuse but miserably stray.

All did depend on Her, but She on none,

For her Philosophy was all her own.

She never did to the poor Refuge fly

Of Occult Quality or Sympathy.

She could a Reason for each Cause present,

Not trusting wholly to Experiment,

No Principles from others she purloyn’d,

But wisely Practice she with Speculation joyn’d. (A Collection, p. 166, emphasis added)

This poem in which these lines appear was penned by the poet Thomas Shadwell, author of The Virtuoso. Shadwell presents the Duchess as holding to a more balanced view of the relative value of practice and speculation than is warranted from her writings. But the fact that he has singled this out is indicative of just how central was this issue to thinkers of the day.

History: “a school of morality to mankind”

Juan Gomez writes…

Throughout the last few years we have presented a number of posts on education and experimental philosophy in the Early Modern period. Peter Anstey and Alberto Vanzo have commented on teaching experimental philosophy (Desaguliers, Adams, and Meiners), Gerard Wiesenfelt delighted us with two posts on universities in seventeenth-century Europe (Sturm and de Volder), and I have discussed education in Aberdeen (Fordyce and Gerard) and England (Bentham). Today I want to contribute to our research on education by discussing Turnbull’s ideas on learning and virtue.

Even though scholars have recognized that there were significant developments in educational theory in the Early Modern Period, almost all of their accounts are French-centred and the only British author they refer to is Locke, due to his influential Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693). Of course, the bulk of the educational treatises of the eighteenth century were produced by French authors (Voltaire, Rollins, Diderot, Condorcet, etc.), but this does not mean that important works on education were not being produced outside of France. Turnbull’s Observations upon Liberal Education (1742) is a salient example here. Turnbull (with the exception of a recent article by Tal Gilead) is hardly even mentioned in scholarly accounts of education in the eighteenth-century, despite the fact that his book on education had a considerable impact at the time. Besides having a clear influence on Alexander Gerard and the educational reforms in the Aberdeen universities after 1750, Turnbull also appears as a major influence in Benjamin Franklin’s Proposals Relating to the Education of the Youth in Pennsylvania (1749). Further, even though many of the ideas in Turnbull’s Education also appear in Locke and Rollins’ work, Turnbull’s commitment to the experimental methodology gives his text a unique feature among the educational works of the time.

Turnbull, like Locke and Rollins before him, firmly believes that the main goal of education is the teaching of virtue. This popular idea of the time takes on a unique development in Education, where Turnbull applies the experimental method to his pedagogical theory:

- …as with regard to the culture of plants or flowers, sure rules can only be drawn from experiment; so for the same reason, there can be no sure rules concerning education but those which are founded on the experimental knowledge of human nature.

So where are we to find the experiments Turnbull hints at? If the aim of education is the achievement of virtue, then those experiments must contribute to this same purpose. We have already discussed that paintings can take on this role. However, in Education the role of experiments is taken up by the example of teachers and of historical characters. Turnbull refers to Horace to illustrate this method of educating:

- For ’tis by examples that good and bad conduct, with their various effects and consequences, the strength and grace to which men, by proper diligence, may arrive, and the baseness and misery into which vice plunges, most strongly appear…This, indeed, is the moral lesson every more exalted example in the records of human affairs presents to us in the most striking light, and to which cannot be too early or too forcibly inculcated from fact and experience… The characters of the more considerable personages of moral history, will afford, to a judicious instructor, excellent opportunities of enforcing, of deeply riveting this important lesson upon young minds.

History takes a primary role in Turnbull’s theory of education, given that it furnishes us with the experiments that allow us to direct the mind towards virtue. In another of his texts, a preliminary discourse to a translation of Justin’s History of the world (1742), Turnbull paraphrases Rollin to illustrate the priority of teaching history:

- History therefore, when it is well taught, becomes a school of morality to mankind, of all conditions and ranks. It discovers the deformity and fatal consequences of vices, and unmasks false virtues; it disabuses men of their popular errors and prejudices; and despoiling riches of all its enchanting and dazzling pomp and magnificence, demonstrates by a thousand examples, which are more persuasive than reasonings, that there is nothing truly great or praise-worthy, but untainted honour and probity.

Rollin and Turnbull share this belief in the supreme importance of history for teaching virtue, but unlike the former’s, Turnbull’s theory stands on his belief that the experimental method is the proper way of gaining any kind of knowledge. One of Turnbull’s original and interesting contributions to eighteenth-century educational theory is his interpretation of historical accounts as proper examples that provides us with adequate facts and observations for the instruction of virtue, in the same way experiments allow us to construct our conclusions in natural philosophy. Of course, the question of the accuracy of historical reports springs up; can inaccurate or false historical reports still contribute to the instruction of virtue? For example, an historical account that somehow illustrates that greed leads to happiness and the progress of society would not, presumably, be of service to the goal of education that Turnbull wishes. However, by insisting on the importance of the experimental method Turnbull has a way out: only those historical accounts that are founded on facts and observations are to be considered in the education of our youth. Turnbull did not deal with this issue in enough detail in Education, but he did discuss the issue of the reliability of historical reports in another context (religious testimony) which we will explore in my next post.

The formation of Boyle’s experimental philosophy

Peter Anstey writes …

It is not entirely clear when Robert Boyle (1627–1691) first used the term ‘experimental philosophy’, but what is clear is that his views on this new approach to natural philosophy began to form in the early 1650s, some years before the term came into common use.

Boyle’s earliest datable use of the term is from his Spring of the Air published in 1660. The reason for the lack of clarity about Boyle’s first use of the term arises from the fact that what appears to be a very early usage survives only in a fragment published by Thomas Birch in his ‘Life of Boyle’ in 1744: no manuscript version is extant. The context of Boyle’s reference to experimental philosophy in this text suggests that this fragment is associated with his ‘Essay of the Holy Scriptures’ composed in the mid-1650s. Boyle speaks of:

those excellent sciences, the mathematics, having been the first I addicted myself to, and was fond of, and experimental philosophy with its key, chemistry, succeeding them in my esteem and applications …

(Works of Robert Boyle, eds Hunter and Davis, London, vol. 12, p. 356)

However, the question of the precise dating of Boyle’s use of the term is hardly as significant as the formation of his views on his distinctive form of natural philosophy. And on this point we have some fascinating and chronologically unambiguous evidence, namely, Boyle’s outline of a work ‘Of Naturall Philosophie’ which dates from around 1654. This short manuscript in Boyle’s early hand survives among the Royal Society Boyle Papers in volume 36, folios 65–6. (It is transcribed in full in Michael Hunter, Robert Boyle 1627–1691: Scrupulosity and Science (Woodbridge, 2000), 30–1.)

In it Boyle outlines the two ‘Principles of naturall Philosophie’. They are Sense and Reason. As for Sense, in addition to its fallibility, Boyle stresses that:

it is requisite to be furnished with observations and Experiments.

Boyle then proceeds to give a set of seven ‘Directions concerning Experiments’. These directions provide an early adumbration of his later experimental methodology. They include the following:

1. Make all your Experiments if you can your selfe [even] though you be satisfyed beforehand of the Truth of them.

3. Be not discouraged from Experimentinge by haveing now & then your Expectation frustrated

5. Get acquainted with Experimentall Books & Men particularly Tradesmen.

7. After you have made any Experiment, not before, reflect upon the uses & Consequences of it either to establish truths, detect Errors, or improve some knowne or give hints of some new Experiment

As for the principle of Reason, Boyle gives five considerations concerning it. What is striking here is that each of them concerns the relation between Reason and experiments:

- That we consult nature to make her Instruct us what to beleeve not to confirme what we have beleeved

- That a perfect account of noe Experiment is to be looked for from the Experiment it selfe

- That it is more difficult then most men are aware of to find out the Causes of knowne effects

- That it is more difficult then men thinke to build principles upon or draw Consequences from Experiments

- That therefore Reason is not to be much trusted when she wanders far from Experiments & Systematical Bodyes of naturall Philosophie are not for a while to be attempted

Note here the caution about the difficulty of building natural philosophical principles from experiments and the warning about wandering from experiments and premature system building, points that were to become key motifs of the experimental philosophy that blossomed in the 1660s.

It may well be that the movement of experimental philosophy did not emerge until the early 1660s, but the conceptual foundations of its most able exponent were laid nearly a decade before.

Are there any parallel cases of natural philosophers who worked out an experimental philosophy in the early 1650s or was Boyle the first?

Observation and Experiment in the Opticks: A Baconian Interpretation

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In a recent post, I considered Newton’s use of observation and experiment in the Opticks. I suggested that there is a functional (rather than semantic) difference between Newton’s ‘experiments’ and ‘observations’. Although both observations and experiments were reports of observations involving intervention on target systems and manipulation of independent variables, experiments offered individual, and crucial, support for particular propositions, whereas observations only supported propositions collectively.

At the end of the post, I suggested that, if we view them as complex, open ended series’ of experiments, the observations of books 2 and 3 look a lot like what Bacon called ‘experientia literata’, the method by which natural histories were supposed to be generated. In this post, I’ll discuss this suggestion in more detail, following Dana Jalobeanu’s recent work on Bacon’s Latin natural histories and the art of ‘experientia literata’.

The ‘Latin natural histories’ were Bacon’s works of natural history, as opposed to his works about natural history. A notable feature of Bacon’s Latin natural histories is that they were produced from relatively few ‘core experiments’. By varying these core experiments, Bacon generated new cases, observations and facts. The method by which this generation occurs is called the art of ‘experientia literata’. Experientia literata (often referred to as ‘learned experience’) was a late addition to Bacon’s program, developed in De Augmentis scientiarum (1623). It is a tool or technique for guiding the intellect. By following this method, discoveries will be made, not by chance, but by moving from one experiment to the next in a guided, systematic way.

The following features were typical of the experientia literata:

- The series of observations was built around a few core experiments;

- New observations were generated by the systematic variation of experimental parameters;

- The variation could continue indefinitely, so the observation sequence was open-ended;

- The experimental process itself could reveal things about the phenomena, beyond what was revealed by a collection of facts;

- The trajectory of the experimental series was towards increasingly general facts about the phenomena; and

- The results of the observations were collated and presented as tables. These constituted the ‘experimental facts’ to be explained.

Now let’s turn to Newton’s observations. For the sake of brevity, my discussion will focus on the observations in book 2 part I of the Opticks, but most of these features are also found in the observations of book 2 part IV, and in book 3 part I.

Figure 1 (Opticks, book 2 part I)

The Opticks book 2 concerned the phenomenon now known as ‘Newton’s Rings’: the coloured rings produced by a thin film of air or water compressed between two glasses. Part I consisted of twenty-four observations. Observation 1 was relatively simple: Newton pressed together two prisms, and noticed that, at the point where the two prisms touched, there was a transparent spot. The next couple of observations were variations on that first one: Newton rotated the prisms and noticed that coloured rings became visible when the incident rays hit the prisms at a particular angle. Newton progressed, step-by-step, from prisms to convex lenses, and then to bubbles and thin plates of glass. He varied the amount, colour and angle of the incident light, and the angle of observation. The result was a detailed, but open ended, survey of the phenomena. Part II consisted of tables that contained the results of part I. These constituted the experimental facts to be explained in propositions in part III. In part IV, Newton described a new set of observations, which built on the discussions of propositions from part III.

When we consider Newton’s observations alongside Bacon’s experientia literata, we notice some common features.

Firstly, the series of observations was built around the core experiment involving pressing together two prisms to observe the rings that appeared.

Secondly, new observations were generated by the variation of experimental parameters: i.e. new observations were generated, first by varying the obliquity of the incident rays, then by varying the glass instruments, then by varying the colour of the incident light, and so on.

Thirdly, the sequence of observations was open-ended. Newton could have extended the sequence by varying the medium, or some other experimental parameter. Moreover, at the end of the sequence, Newton noted further variations to be carried out by others, which might yield new or more precise observations.

Fourthly, the experimental process itself revealed things about the phenomenon, beyond what was revealed by a collection of facts. For example, in observation 1, Newton noticed that increasing the pressure on the two prisms produced a transparent spot. The process of varying the pressure, and hence the thickness of the film of air between the two prisms, suggested to Newton a way of learning more about the phenomenon of thin plates. He realised he could quantify the phenomenon by introducing regularly curved object glasses, which would make the variation in thickness regular, and hence, calculable.

Fifthly, the trajectory of the experimental series was towards increasingly general facts about the phenomenon. Newton began by simply counting the number of rings and describing the sequence of colours under specific experimental parameters. But eventually he showed that the number of rings and their colours was a function of the thickness and density of the film. Thus, he was able to give a much broader account of the phenomenon.

Finally, these general results were collated and presented as tables in part II. Thus, the tables in part II constituted the facts to be explained by propositions in part III.

Many commentators have emphasised the ways that Newton deviated from Baconian method. However, when viewed in this light, book 2 of the Opticks provides a striking example of conformity to the Baconian method of natural history: Newton led the reader from observations in part I, to tables of facts in part II, to propositions in part III. Moreover, it ended with a further series of observations in part IV, emphasising the open-endedness of the art of experientia literata.

In contrast to the observations in book 2, Newton’s experiments in book 1 look like Bacon’s ‘instances of special power’, which are particularly illuminating cases introduced to provide support for specific propositions. I’ll discuss this next time. For now, I’d like to hear what our readers think of my Baconian interpretation of Newton’s observations.

Experimental philosophy and religion

Peter Anstey writes …

From the first decade of its existence early modern experimental philosophy enjoyed an intimate relation with Christianity. This manifested itself in at least two ways. First, experimental philosophy, it was argued, was a great help in the development of the mind and character of the Christian. Second, and later, it came to play a central role in Christian apologetics. As for experimental philosophy and Christian living, some of the Fellows of the early Royal Society like Joseph Glanvill wrote extensively on the theme of the positive benefits of the practice of experimental philosophy for Christians. See, for example, Glanvill’s Philosopia Pia: or a Discourse of the Religious Temper, and Tendencies of the Experimental Philosophy (1671).

Once experimental philosophy had consolidated its position as a prominent new approach to natural philosophy it began to be used for the purposes of Christian apologetics. In Robert Boyle experimental philosophers had the archetypal Christian virtuoso who not only manifested the benefits of practising Christianity in his character but also did much to promote the link between the new experimental natural philosophy and the defense of the faith. In The Christian Virtuoso he claimed that:

the Experimental Philosophy giving us a more clear discovery, …, of the divine Excellencies display’d in the Fabrick and Conduct of the Universe, and of the Creatures it consists of, … leads it [the mind] directly to the acknowledgment and adoration of a most Intelligent, Powerful and Benign Author of things. (Works of Robert Boyle, 14 vols, eds Hunter and Davis, London, 1999–2000, 11, 293)

Boyle’s ultimate legacy in this regard was the provision in his will for the Boyle Lectures. And it was the inaugural Boyle Lecturer, Richard Bentley, who first mobilized Newton’s new natural philosophy in Christian apologetics in his seventh lecture, published after extensive correspondence with Newton himself (The Folly and Unreasonableness of Atheism, 1693). Once the precedent was established it was continued and augmented in works such as George Cheyne’s Philosophical Principles of Natural Religion (1705), William Derham’s Astro-Theology: or a Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God, from a Survey of the Heavens (1715) and William Whiston’s Astronomical Principles of Religion, Natural and Revealed (1717).

Interestingly, it was actually the connection with religion that first raised the reading public’s consciousness of experimental philosophy in the Netherlands. For, it is now thought that the publication of Bernard Nieuwentijt’s Het regt gebruik in 1715 marks an important moment in the awakening to experimental philosophy in Holland. This work was translated into English in 1718 by Peter Chamberlayne as The Religious Philosopher with a prefatory letter to the translator by the leading pedagogue of experimental philosophy in England, John Theophilus Desaguliers. Desaguliers commends the work because:

it contains several fine Observations and Experiments, which are altogether new, as is also his manner of treating the most common Phaenomena; from which he deduces admirable Consequences in favour of a Religious Life.

Likewise, Ten Kate’s Dutch adaptation of George Cheyne’s Philosophical Principles of Natural Religion published in Amsterdam in 1716 turned experimental philosophy to apologetical use. Kate claims ‘some distinguished men in England, who disliked the uncertainties of hypotheses [of Cartesianism], have based themselves only on a Philosophia Experimentalis, by means of mathematics’ (Jorink and Zuidervaart, Newton and the Netherlands: how Isaac Newton was Fashioned in the Dutch Republic, 2012, 31). He drew a strong connection between Newton’s natural philosophy and evidence for God’s hand in creation.

Here then, we have an obvious difference between early modern experimental philosophy and its contemporary namesake. I would value references to other works, particularly works in languages other than English, that discuss the practical and apologetical benefits of experimental philosophy to the Christian religion. Let me know if you can help.

Halley’s Comet and Christmas Day

Kirsten Walsh writes…

Hello Readers!

Since this is our last post for the year, and the holidays are almost upon us, I thought I’d tell you a Christmas story:

On Christmas day in 1758, Johann Georg Palitzsch, a German farmer and amateur astronomer, became the first person to witness the return of, what would become known as, Halley’s comet.

Halley’s comet is the only short-period comet (i.e. comet that completes an orbit in under 200 years) that is visible with the naked eye. It has featured in astronomical reports since at least 240 BC. However, it wasn’t until 1705 that it was recognised as the same object. That year, the English astronomer Edmund Halley determined the periodicity of the comet, writing about it in his Synopsis Astronomia Cometicae. With the help of Newton’s theories of elliptical orbit, Halley had studied the data of the comets that had appeared in 1531, 1607 and 1682, and recognised that they all followed similar paths. He made a rough estimate that the comet would return in 1758.

Halley died in 1742, and so he never saw the return of the comet. But Palitzsch’s Christmas day observation confirmed his claim that, indeed, there was a comet, visible by the naked eye, that had period of approximately 76 years. It was the first time anything other than a planet had been shown to orbit the earth. In 1759, the French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille named the comet after Halley.

This prediction counts, not only as a confirmation of Halley’s theory, but also of Newtonian physics, and of the mathematico-experimental method more generally. It seems fitting that this confirmation happened on the 116th anniversary of Newton’s birth!*

We at Early Modern Experimental Philosophy wish you a happy holiday. We look forward to hearing from you in 2014!

*Actually, Newton was born in England on 25 December 1642, but Palitzsch saw Halley’s comet in Germany on 25 December 1758. Until 1752, England used the Julian (‘Old Style’) calendar, whereas Europe had adopted the Gregorian (‘New Style’) calendar much earlier. There is a 10-day difference between the two calendars, so Newton’s birthdate adjusts to 4 January 1643 on the Gregorian calendar. So while both events happened on Christmas day, they happened on different Christmas days. (Also, I hope you will forgive me for this picture, that I couldn’t resist posting!)

Birth stats and Divine Providence

Juan Gomez writes…

In a number of posts in this blog we have examined how some philosophers in the eighteenth century were carrying out moral enquiries by following the experimental method that had achieved so much for natural philosophers. The subtitle of Hume’s famous Treatise clearly states the “attempt to introduce the experimental method in morals,” and we know that Turnbull, Butler and Hutcheson were also using this method in their arguments regarding morality, the human mind, and the existence of God. Regarding this latter issue, theistic philosophers like Butler and Turnbull argued that the order and perfection of the natural world (deduced from facts and observation) was clear proof of the wisdom and goodness of God. In this post I want to examine one of such arguments given not by a moral philosopher, but by a famous physician and mathematician: Dr. John Aburthnot.

Dr. Arbuthnot was a fellow of the Royal Society and Physician to the Queen, a fellow Scriblerian of Swift and Pope, a mathematician and a very interesting figure in general. Best known for his work in medicine and his satires, this fascinating polymath wrote a short paper that appeared in the Philosophical Transactions for 1710 titled “An Argument for Divine Providence, Taken from the Constant Regularity Observ’d in the Births of Both Sexes.” He explains how probability works in a situation involving a two-sided dice, and then proceeds to argue that the number of males and females born in England from 1629 to 1710 shows that it was not mere chance, but rather Divine Providence that explains the regularity between the sexes. Let’s examine his argument in more detail.

Arbuthnot begins by considering the purely mathematical aspect of an event where we want to find out the chances of throwing a particular number of two-sided dice (or a coin for that matter). The simplest case is that of 2 coins, where we have that there is one chance of both coins landing on heads, one chance of both coins landing on tails, and two chances where each of the coins lands on a different side. The mathematical details need not detain us here; the main conclusion drawn form this exposition is that the chances of getting an equal number of heads and tails grows slimmer as the number of coins augments. For example, the chances of this happening with ten coins is less than 25%. If instead of coins we consider all human beings which, Arbuthnott assumes, are born either male or female, the chances of there being equal number of each of the sexes are very, very low.

However, Arbuthnot acknowledges that the physical world is not equivalent to the mathematical, and this changes his calculations. If it was just mere chance that operated in the world, the balance between the number of males and females would lean to one or the other, and perhaps even reach extremes. But this is not the case. In fact, or so Arbuthnott argues, nature has even taken into account the fact that males have a higher mortality rate than females, given that the former “must seek their Food with danger…and that this loss exceeds far that of the other Sex, occasioned by Diseases incident to it, as Experience convinces us.” The wisdom of the Author of nature is witnessed in this situation, as the tables of births in England show that every year slightly more males than females are born, in order to compensate for the loss mentioned above and keep the balance. For example in 1629, Arbuthnot’s table list 5218 males to 4683 females; in 1659, 3209 males to 2781 females; in 1709, 7840 males to 7380 females; and so on for all the years recorded.

Arbuthnot concludes that from his argument “it follows, that it is Art, not Chance , that governs,” and adds a scholium where he states that polygamy is contrary to the law of nature.

What can we make of Arbuthnot’s paper? Instead of discussing how effective the argument is (I leave that for the readers to discuss with us in the comments!!), I want to focus on the fact that Arbuthnot’s argument illustrates the call for the use of mathematics in natural philosophy. Philosophers like Arbuthnot and John Keill thought that the use of mathematics had been neglected in natural philosophy and believed that it should play a greater role. From the 1690’s onwards the work of experimental philosphers reveals this use of mathematics in natural philosophical reasoning. The structure of Arbuthnot’s argument resembles that of the natural philosophers who, like Newton, were using mathematics to explain natural phenomena. The mathematical calculation is extrapolated to the case of human births (in this case). Arbuthnot recognizes an issue central to the application of maths in natural philosophy: while the former deals with abstract objects, the latter deals with the natural world. However, in this particular case Arbuthnot uses the asymmetry between the mathematical and physical realms to show that Divine Providence is a better explanation than mere chance when it comes to the balance and regularity of human births. I would like to hear what our readers think of arguments like the one constructed by Arbuthnot.