Observation and Experiment in the Opticks: A Baconian Interpretation

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In a recent post, I considered Newton’s use of observation and experiment in the Opticks. I suggested that there is a functional (rather than semantic) difference between Newton’s ‘experiments’ and ‘observations’. Although both observations and experiments were reports of observations involving intervention on target systems and manipulation of independent variables, experiments offered individual, and crucial, support for particular propositions, whereas observations only supported propositions collectively.

At the end of the post, I suggested that, if we view them as complex, open ended series’ of experiments, the observations of books 2 and 3 look a lot like what Bacon called ‘experientia literata’, the method by which natural histories were supposed to be generated. In this post, I’ll discuss this suggestion in more detail, following Dana Jalobeanu’s recent work on Bacon’s Latin natural histories and the art of ‘experientia literata’.

The ‘Latin natural histories’ were Bacon’s works of natural history, as opposed to his works about natural history. A notable feature of Bacon’s Latin natural histories is that they were produced from relatively few ‘core experiments’. By varying these core experiments, Bacon generated new cases, observations and facts. The method by which this generation occurs is called the art of ‘experientia literata’. Experientia literata (often referred to as ‘learned experience’) was a late addition to Bacon’s program, developed in De Augmentis scientiarum (1623). It is a tool or technique for guiding the intellect. By following this method, discoveries will be made, not by chance, but by moving from one experiment to the next in a guided, systematic way.

The following features were typical of the experientia literata:

- The series of observations was built around a few core experiments;

- New observations were generated by the systematic variation of experimental parameters;

- The variation could continue indefinitely, so the observation sequence was open-ended;

- The experimental process itself could reveal things about the phenomena, beyond what was revealed by a collection of facts;

- The trajectory of the experimental series was towards increasingly general facts about the phenomena; and

- The results of the observations were collated and presented as tables. These constituted the ‘experimental facts’ to be explained.

Now let’s turn to Newton’s observations. For the sake of brevity, my discussion will focus on the observations in book 2 part I of the Opticks, but most of these features are also found in the observations of book 2 part IV, and in book 3 part I.

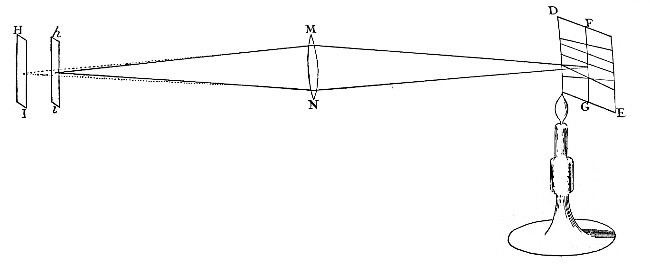

Figure 1 (Opticks, book 2 part I)

The Opticks book 2 concerned the phenomenon now known as ‘Newton’s Rings’: the coloured rings produced by a thin film of air or water compressed between two glasses. Part I consisted of twenty-four observations. Observation 1 was relatively simple: Newton pressed together two prisms, and noticed that, at the point where the two prisms touched, there was a transparent spot. The next couple of observations were variations on that first one: Newton rotated the prisms and noticed that coloured rings became visible when the incident rays hit the prisms at a particular angle. Newton progressed, step-by-step, from prisms to convex lenses, and then to bubbles and thin plates of glass. He varied the amount, colour and angle of the incident light, and the angle of observation. The result was a detailed, but open ended, survey of the phenomena. Part II consisted of tables that contained the results of part I. These constituted the experimental facts to be explained in propositions in part III. In part IV, Newton described a new set of observations, which built on the discussions of propositions from part III.

When we consider Newton’s observations alongside Bacon’s experientia literata, we notice some common features.

Firstly, the series of observations was built around the core experiment involving pressing together two prisms to observe the rings that appeared.

Secondly, new observations were generated by the variation of experimental parameters: i.e. new observations were generated, first by varying the obliquity of the incident rays, then by varying the glass instruments, then by varying the colour of the incident light, and so on.

Thirdly, the sequence of observations was open-ended. Newton could have extended the sequence by varying the medium, or some other experimental parameter. Moreover, at the end of the sequence, Newton noted further variations to be carried out by others, which might yield new or more precise observations.

Fourthly, the experimental process itself revealed things about the phenomenon, beyond what was revealed by a collection of facts. For example, in observation 1, Newton noticed that increasing the pressure on the two prisms produced a transparent spot. The process of varying the pressure, and hence the thickness of the film of air between the two prisms, suggested to Newton a way of learning more about the phenomenon of thin plates. He realised he could quantify the phenomenon by introducing regularly curved object glasses, which would make the variation in thickness regular, and hence, calculable.

Fifthly, the trajectory of the experimental series was towards increasingly general facts about the phenomenon. Newton began by simply counting the number of rings and describing the sequence of colours under specific experimental parameters. But eventually he showed that the number of rings and their colours was a function of the thickness and density of the film. Thus, he was able to give a much broader account of the phenomenon.

Finally, these general results were collated and presented as tables in part II. Thus, the tables in part II constituted the facts to be explained by propositions in part III.

Many commentators have emphasised the ways that Newton deviated from Baconian method. However, when viewed in this light, book 2 of the Opticks provides a striking example of conformity to the Baconian method of natural history: Newton led the reader from observations in part I, to tables of facts in part II, to propositions in part III. Moreover, it ended with a further series of observations in part IV, emphasising the open-endedness of the art of experientia literata.

In contrast to the observations in book 2, Newton’s experiments in book 1 look like Bacon’s ‘instances of special power’, which are particularly illuminating cases introduced to provide support for specific propositions. I’ll discuss this next time. For now, I’d like to hear what our readers think of my Baconian interpretation of Newton’s observations.

Observation, experiment and intervention in Newton’s Opticks

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In my last post, my analysis of the phenomena in Principia revealed a continuity in Newton’s methodology. I said:

- In the Opticks, Newton isolated his explanatory targets by making observations under controlled, experimental conditions. In Principia, Newton isolated his explanatory targets mathematically: from astronomical data, he calculated the motions of bodies with respect to a central focus. Viewed in this way, Newton’s phenomena and experiments are different ways of achieving the same thing: isolating explananda.

In this post, I’ll have a closer look at Newton’s method of isolating explananda in the Opticks. It looks like Newton made a distinction between experiment and observation: book 1, contained ‘experiments’, but books 2 and 3, contained ‘observations’. I’ll argue that the distinction in operation here was not the standard one, which turns on level of intervention.

In current philosophy of science, the distinction between experiment and observation concerns the level of intervention involved. In scientific investigation, intervention has two related functions: isolating a target system, and creating novel scenarios. On this view, experiment involves intervention on a target system, and manipulation of independent variables. In contrast, the term ‘observation’ is usually applied to any empirical investigation that does not involve intervention or manipulation. This distinction is fuzzy at best: usually level of intervention is seen as a continuum, with observation nearer to one end and experiment nearer to the other.

If Newton was working with this sort of distinction, then we should find that the experiments in book 1 involve a higher level of intervention than the observations in books 2 and 3. That is, in contrast to the experiments in book 1, the observations should involve fewer prisms, lenses, isolated light rays, and artificially created scenarios. However, this is not what we find. Instead we find that, in every book of the Opticks, Newton employed instruments to create novel scenarios that allowed him to isolate and identify certain properties of light. It is difficult to quantify the level of intervention involved, but it seems safe to conclude that Newton’s use of the terms ‘observation’ and ‘experiment’ doesn’t reflect this distinction.

To understand what kind of distinction Newton was making, we need to look at the experiments and observations more closely. In Opticks book 1, Newton employed a method of ‘proof by experiments’ to support his propositions. Each experiment was designed to reveal a specific property of light. Consider for example, proposition 1, part I: Lights which differ in Colour, differ also in Degrees of Refrangibility. Newton provided two experiments to support this proposition. These experiments involved the use of prisms, lenses, candles, and red and blue coloured paper. From these experiments, Newton concluded that blue light refracts to a greater degree than red light, and hence that blue light is more refrangible than red light.

Opticks, part I, figure 12.

In the scholium that followed, Newton pointed out that the red and blue light in these experiments was not strictly homogeneous. Rather, both colours were, to some extent, heterogeneous mixtures of different colours. So it’s not the case, when conducting these experiments, that all the blue light was more refrangible than all the red light. And yet, these experiments demonstrate a general effect. This highlights the fact that, in book 1, Newton was describing ideal experiments in which the target system had been perfectly isolated.

Book 2 concerned the phenomenon now known as ‘Newton’s Rings’: the coloured rings produced by a thin film of air or water compressed between two glasses. It had a different structure to book 1: Newton listed twenty-four observations in part I, then compiled the results in part II, explained them in propositions in part III, and described a new set of observations in part IV. The observations in parts I and IV explored the phenomena of coloured rings in a sequence of increasingly sophisticated experiments.

Consider, for example, the observations in part I. Observation 1 was relatively simple: Newton pressed together two prisms, and noticed that, at the point where the two prisms touched, there was a transparent spot. The next couple of observations were variations on that first one: Newton rotated the prisms and noticed that coloured rings became visible when the incident rays hit the prisms at a particular angle. But Newton steadily progressed, step-by-step, from prisms to convex lenses, and then to bubbles and thin plates of glass. He varied the amount, colour and angle of the incident light, and the angle of observation. The result was a detailed, but open ended, survey of the phenomena.

I have argued that Newton’s experiments and observations cannot be differentiated on the basis of intervention, but there are two other differences worth noting. Firstly, whereas the experiments described in book 1 were ideal experiments, involving perfectly isolated explanatory targets, the observations in books 2 and 3 were not ideal. Rather, through a complex sequence of observations, as the level of sophistication increased, the explanatory target was increasingly well isolated. When viewed in this way, the phenomena of Principia seem to have more in common with the experiments of book 1 than the observations of books 2 and 3.

Secondly, the experiments of book 1 were employed to support particular propositions, and so, individually, they were held to be particularly relevant and informative. In contrast, the observations of books 2 and 3 were only collectively relevant and informative. Moreover, the sequence of observations was open ended: there were always more variations one could try.

What are we to make of these differences between observation and experiment in the Opticks? I have previously argued that, while Newton never constructed Baconian natural histories, his work contained other features of the Baconian experimental philosophy, such as experiments, queries and an anti-hypothetical stance. However, in viewing them as complex, open ended series’ of experiments, I now suggest that the observations of books 2 and 3 look a lot like what Bacon called experientia literata, the method by which natural histories are generated. I’ll discuss this in my next post, but in the mean time, I’d like to hear what our readers think.