Two Forms of Natural History

Peter Anstey writes…

There were two forms of natural history in the early modern period: traditional natural history and Baconian natural history. The distinction between them becomes clear in the light of the development of the experimental philosophy in the mid-17th century. Unfortunately, however, this distinction is almost always elided in the secondary literature on natural history.

Traditional natural history, deriving from Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides, had flourished in the late Renaissance. It involved the mapping of nature through the classification of plants and animals and the assembling of information about their uses and habits. This traditional natural history continued throughout the 17th century and reached its zenith in the 18th century in the work of the likes of Carl Linnaeus. But this was neither the only form of natural history, nor, for that matter, was it the most important form for the experimental philosophers. Let me explain.

The experimental philosophy of the seventeenth century developed as a method of knowledge acquisition in natural philosophy. However, unlike the division between science and philosophy today, in the early modern period natural philosophy and philosophy were not regarded as discrete disciplinary domains. Natural philosophy was thought to be the philosophy of nature, rather than, say, the philosophy of morality or metaphysics. Thus Descartes’ Principles of Philosophy are principles of natural philosophy and this work presents his mature natural philosophical system.

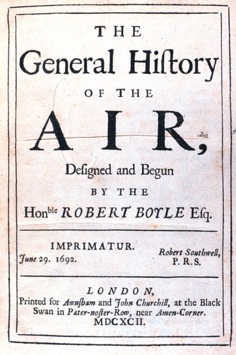

Robert Boyle's General History of the Air

The experimental philosophy was initially developed and applied in the study of nature and only later was it applied more broadly to the other parts of philosophy. The first ‘version’ of the experimental philosophy was the Baconian method of natural history. This was inspired by Francis Bacon’s grand scheme for the renovation of knowledge of nature and in particular his novel approach to natural history.

The Baconian method involved the assembling of vast amounts of data about particular substances, qualities or states of bodies. In this way it was far broader in its scope than traditional natural history. To be sure, it included facts about generations––that is animal, plant and insect species-–but it included much more, such as histories of cold, of the air, of electrostatic phenomena and of fluidity and solidity, etc. According to the Baconian method, once all of the facts were collected they were to be ordered and structured in such a way as to facilitate theoretical, or speculative, reflection upon the phenomenon at hand. Thus, once all the facts about, say, human blood or the air, were gathered, then the natural philosopher would be in a position to develop a true and accurate philosophy of the blood or air.

It was this method that was developed in a detailed and sophisticated way by the early Royal Society and which became popular across Europe in the second half of the 17th century. This Baconian natural history encompassed traditional natural history and as a result traditional natural history flourished under its aegis. But, the Baconian form of natural history was short-lived: it was in serious decline in the 1690s and all but disappeared in the first decades of the 18th century. All the while traditional natural history was going from strength to strength and was soon to become one of the most important branches of 18th century science.

The reasons for the decline of Baconian natural history need not detain us here, but the reason for the eliding of the distinction between it and traditional natural history is of great importance. I contend that scholars have failed to distinguish between the two because of their failure to appreciate the nature and significance of the experimental philosophy in general. When we view early modern natural history through the lens of the experimental philosophy the distinction between the two forms of natural history becomes clear. This is another reason why, as I claimed in an earlier post, ESP is best!

Baconian versus Newtonian experimental philosophy

Peter Anstey writes…

Eric Schliesser’s comments about the utility of the experimental/speculative distinction, provide an opportunity for me to lay out a distinction that is absolutely central to our project. But let’s hear from Eric first: I quote from his blog post on It’s Only a Theory:

- It ignores at least one other group of philosophers, namely those that believed in (mathematical) theory mediated measurement. I am thinking of Galileo, Huygens, and Newton, among the best known. These are not best described as experimental, although all were accomplished experimentalists (and Newton’s Optics is often assimilated to experimental traditions), but their work has very different character from say, Bacon or Boyle. (They are also not best described as speculative, because all three practiced a self-restraint on published speculation.) Certainly after the Principia this approach created standing challenge to all other forms of philosophizing. So the Otago framework will run into big trouble in 18th century.

We’ve already shown that, in fact, the terminology of the experimental philosophy is very prevalent in the 18th century and, moreover, that the experimental philosophy was extended beyond natural philosophy into moral philosophy and even aesthetics. See, for example, the works of George Turnbull which are a good example of experimental moral philosophy.

But the important issue Eric raises has to do with those who practised ‘theory mediated measurement’ such as Galileo, Huygens and Newton. What our research has shown is that the experimental philosophy was practised in two quite different ways. Up until the 1690s, Boyle, Hooke and the early Royal Society practised experimental philosophy according to the method of Baconian natural history. However, from the last decade of the seventeenth century Newton’s new mathematical natural philosophical method came to be seen as the preferred method of experimental philosophy. The Baconian natural history program started to run out of steam in the 1690s and it soon came to be replaced by the Newtonian method. This is, in fact, the explanation of Newton’s common refrain ‘Natural philosophy is not natural history’. And Newton himself had a large hand in the demise of the Baconian approach to experimental philosophy both through criticism and through his own positive alternative. Far from providing an exception to our framework, Newton, the self-confessed experimental philosopher, is one of the central players!