CFP: Creative Experiments

From the Zeta Books website:

The Journal of Early Modern Studies is seeking contributions for its second issue (Spring 2013). It will be a special issue, devoted to the theme:

Creative experiments:

Heuristic and Exploratory Experimentation in Early Modern Science

Editor: Dana Jalobeanu

The past decade has seen a renewed interest in multiple aspects of early modern experimentation: in the cognitive, psychological and social aspects of experiments, in their heuristic and exploratory value and in the complex inter-relations between experience, observation and experiment. Meanwhile, comparatively little has been done towards a more detailed, contextual and specific study of what might be described, a bit anachronistically, as the methodology of early modern experimentation, i.e. the ways in which philosophers, naturalists, promoters of mixed mathematics and artisans put experiments together and reflected on the capacity of experiments to extend, refine and test hypotheses, on the limits of experimental activity and on the heuristic power of experimentation. So far, the sustained interest in the role played by experiments in early modern science has usually centered on ‘evidence’- related problems. This line of investigation favored examination of the experimental results but neglected the “methodology” that brought about the results in the first place. It has also neglected the more creative and exploratory roles that experiments could and did play in the works of sixteenth and seventeenth century explorers of nature.

JEMS is an interdisciplinary, peer-reviewed journal of intellectual history, dedicated to the exploration of the interactions between philosophy, science and religion in Early Modern Europe. It is edited by the Research Centre “Foundations of Modern Thought”, University of Bucharest, and published and distributed by Zeta Books. For further information on JEMS, please visit http://www.zetabooks.com/journal-of-early-modern-studies.html.

We are seeking for articles no longer than 10,000 words, in English or French, with an abstract and key-words in English. Please send your contribution by the 1st of October 2012 to jems@zetabooks.com.

Physics: from experimental philosophy to experimental science

Alberto Vanzo writes…

I have been wondering recently when German thinkers ceased considering physics as a part of philosophy and whether this may be related to the demise of experimental philosophy in late eighteenth-century Germany. I think that this may have well been the case. My hypothesis is that experimental philosophy declined as the result of the influence of Kantian and post-Kantian idealism and that the distinction between physics and philosophy gained foot in the 1830s and the 1840s as a reaction to post-Kantian idealism. In this post, I would like to expand on this suggestion and ask you for comments and pointers for further research.

As is well-known, physics was generally regarded as a part of philosophy in the early modern age. This is true for most early modern German writers, including several German experimental philosophers who, in the 1770s and 1780s, attempted to develop their systems on the basis of experiments and observations and eschewed hypotheses and a priori speculations. They held that the whole of philosophy relied on the same method as physics.

In the last two decades of the eighteenth century, Kantian and post-Kantian philosophies came to dominate the philosophical scene and eclipsed the German tradition of experimental philosophy. Kant vindicated a metaphysics based on a priori reasonings rather than observations and experiments. Kant held that we can discover some features of the natural world a priori. He distinguished this a priori, metaphysical study of nature from empirical, experimental physics, which he regarded as a part of philosophy too. However, at the end of the Critique of Pure Reason he introduced a narrow notion of philosophy that includes only a priori disciplines and excludes empirical physics from the domain of philosophy:

- Thus the metaphysics of nature as well as morals, but above all the preparatory (propaedeutic) critique of reason that dares to fly with its own wings, alone constitute that which we can call philosophy in a genuine sense. (A850/B878)

Early-day Kantians agreed with Kant that experimental physics was part of philosophy in the broad sense, but not of philosophy in the narrow sense. However, many of their pronouncements imply that physics (tacitly identified with experimental physics) is not part of philosophy (tacitly identified with Kant’s narrow notion of philosophy). For instance, the Kantian Johann Gottlieb Buhle wrote that, when seventeenth-century writers used the expression “Cartesian philosophy”, they were often thinking “about his physics and cosmogony rather than about his philosophy in the proper sense”. With statements like this, Kant and his disciplines promoted a division of labour between the a priori inquiries of philosophers and the a posteriori research of physicists.

Did German authors start distinguishing between physics and philosophy once the Neo-Kantians started spreading Kant’s outlook in the 1860s, as Richard Rorty claimed? I believe that several German authors started distinguishing physics from philosophy much earlier, in the 1830s or 1840s. One of the most important events in the German intellectual scene between Kant’s death in 1804 and the 1840s was the rise and decline of post-Kantian idealism. Post-Kantian idealists like Schelling and Hegel pursued an approach to the study of nature that was heavily influenced by their own philosophical speculations (Schelling, for instance, founded a Journal for Speculative Physics). I believe that the tendency to distinguish physics from philosophy spread as a reaction to the attitude of post-Kantian idealists towards physics. The entry “Physik” published in the Brockhaus Conversations-Lexicon in 1833, two years after Hegel’s death, states:

- philosophy, at least in Germany, has again attempted to gain influence on physics. However, after all attempts to found physics from this side [i.e. on philosophy] proved unfruitful, only very few physicists, and actually not the most thorough ones, still believe that they could replace the secure footing that mathematics made possible to give [to physics] with the still very shaky concepts of philosophy. Hence, even if the so-called dynamical conception of physics that is related to this philosophical point of view still survives in some speculations, nevertheless we must admit that now only the mechanical point of view is influential and valid in real-life physics [im Leben der Physik].

Although suggestive, this single quote is hardly sufficient to prove my hypothesis that German authors started distinguishing physics from philosophy as a reaction to the post-Kantian idealistic tendencies that had in turn eclipsed experimental philosophy. Do you think that this view is persuasive? Also, when did physics stop being regarded as a part of philosophy in Great Britain and France? I would be grateful for any comments and suggestions.

Workshop: Letters by Early Modern Philosophers

The workshop is part of the 13th International Conference of the International Society for the Study of European Ideas which will take place in Cyprus on 2-6 July 2012.

The workshop focuses on letters written in the seventeenth century on themes at the border between art, science, and philosophy. A presentation of the workshop topic can be found here.

Abstracts of up to 500 words should be sent to the workshop organiser, Filip Buyse, at filip.buyse1@telenet.be.

Experimental vs Speculative Philosophy in Early Modern Italy

Alberto Vanzo writes…

So far, we have argued in many posts that British philosophers from the 1660s onwards worked in the tradition of experimental philosophy and criticized speculative philosophy. However, the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy was also widely employed outside the British isles. In this post, I will document the presence of the experimental-speculative distinction in Italian natural philosophy between 1667 and 1716.

The Accademia del Cimento, founded by 1657 by Prince Leopoldo de Medici in Florence, was one of the first scientific societies in Europe. In 1667 the Accademia published a collection of experimental reports with the title Saggi di naturali esperienze. The preface to this work ends with a caveat:

- We would not like anyone to believe that we presume to give to the light a complete work, or even only a perfect scheme of a great experimental history, because we know well that more time and strengths are required for such an enterprise […] if, sometimes, an even minimal allusion to anything speculative has been made, […] always take it to be a specific idea or intuition of [some] academics, but never one of the Accademia, whose only aim is to experiment and to narrate.

Note the emphasis on experiments, the references to natural histories, and the refrain from endorsing any speculation. These are all indications that the Academy was presenting its work in terms of the then nascent distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy.

Not everyone was endorsing experimental philosophy in late seventeenth-century Italy. However, some of the authors who expressed reservations towards it did so in terms of the experimental-speculative distinction. For instance, Daniello Bartoli distinguished in 1677

- the two manners of natural philosophy which nowadays are very rumored, because they fight over the glory of primacy […]: the Theoretical and the Experimental […]

On the one hand, theoretical or “purely speculative” philosophy “needs experimental [philosophy] to “see [things] by means of the senses”. On the other hand, “purely experimental” philosophy must seek the help of speculative philosophy to proceed from particular experiences to their causes.

- [E]ither [philosophy], by itself, can be defeated if the other does not help and rescue it when it may fall down. But if both are united and if they fight side by side, although they may not always win, surely they will never be defeated.

Among the Aristotelians, Giovanni Battista de Benedictis (writing under the pseudonym of Benedetto Aletino) criticized experimental philosophy for its inability to proceed from facts to causes. He claimed that experimenters were not philosophers, but mere empirics, because they failed to establish any evident, undisputed premises as the basis for a deductive scientia of nature.

- Indeed, if our Peripatetics, who only paid attention to speculative subtleties, had followed Aristotle’s teachings by directing their efforts towards experience, I have no doubt that they would have unfailingly attained the glory that the Atomists [i.e., experimental philosophers] are now seizing, not because of their knowledge, but because of the neglicence of others [the Peripetetics].

While Aletino defends the Aristotelians, he categorizes them as speculative philosophers and he rejects experimental philosophy.

Antonio Conti was a Venetian abbot who acted as intermediary in the epistolary exchange between Leibniz and Newton. He published a discussion of the relation between experimental and speculative philosophy in 1716. For Conti, experimental philosophy alone “is truly science” because it rely on experience to prove the truth of its claims. By contrast, speculative or conjectural philosophy can only establish the probability or truth-likeliness of hypotheses. Due to the endless variety of nature and the limitations of our senses, Conti did not think that experimental philosophy could eventually supplant all speculations. His fallibilism concerning hypotheses sounds rather modern:

- One makes hypotheses to establish [new] ideas and experiences; but hypotheses last only until phenomena modify or destroy them, or until a more perfect art of comparing truth-likely [statements] proves their uselessness or their imprudence.

Like Bartoli, Conti endorsed experimental philosophy without wholly rejecting the speculative approach. Bartoli and Conti, like Aletino and the compiler of the Saggi di naturali esperienze, thought of natural philosophy in terms of the experimental-speculative distinction. As in the British isles, so also in Italy the experimental-speculative distinction provided important terms of reference for thinking about nature in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.

In this post, I have not discussed to what extent the experimental-speculative distinction shaped the contents, besides the rhetoric and methodology, of Italian natural philosophy. I must do more work to answer that question. In the meanwhile, let me know what you think in the comments.

Hooke’s Knowledge of Optics

This is a guest post by Ian Lawson.

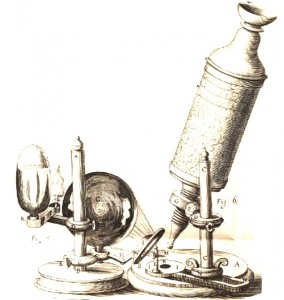

Robert Hooke knew how light worked. He worked with the stuff day in day out during the early 1660s and in Observation IX of his Micrographia (1665) he presents quite a systematic theory of optics.

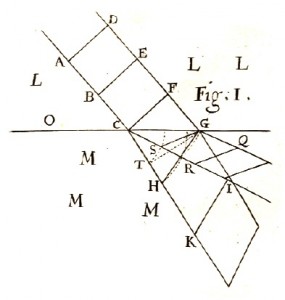

He presents his theory as the result of a startling observation about the colours of the rainbow observable in thin sheets of muscovy glass (mica). This observation he takes to be an ‘experimentum crucis’ against Descartes’ optical theory, ‘serving as a Guide or Land-mark, by which to direct our course in the search after the true cause of Colours’ (Micrographia, p. 54). His positive thesis starts by outlining a hypothesis about light based on some widely accepted principles (though I won’t go into the details here). This hypothesis he checks against more evidence, this time a glass globe filled with water. He finds his idea consistent with the phenomenon, while Descartes is again lacking. An ‘instantia crucis‘ this time – a sure sign he’s on the right track (ibid., p. 59).

To refine his theory, Hooke continues experimenting. Now he uses water in a long glass tube and sheets of muscovy glass split to varying thicknesses. He adds detail until he feels he can account for all kinds of colour phenomena. ‘By this Hypothesis there is no one experiment of colour that I have yet met with, but may be, I conceive, very rationally solv’d, and perhaps, had I time to examine several particulars requisite to the demonstration of it, I might prove it more than probable…’ (ibid., p. 69).

Hooke presents his theory in an ordered and structured way. First he disproves the leading existing theory, then puts forward his own hypothesis. He returns to experiment to check factual adequacy, and uses further trials to refine the general idea. Focusing on his theory as it is presented, though, makes several features of his account mysterious. Why is it tacked on to the end of an observation about colours in a mineral? Why should colour even be the main part of an optical theory? And given that it is, why does he never mention prisms?

What is worth noting is the experiments and observations Hooke makes. There are four primary apparatus he uses:

1. Muscovy glass

2. Glass lenses with water between them

3. Water globes

4. Glass vials filled with water.

Prisms, that paradigmatic optical experimentation device used by Descartes, Boyle, Power, and Newton in their experimenting about colour, are conspicuous by their absence. Rather, all of the experiments mentioned by Hooke are, in fact, part of his everyday set up for making microscopical observations. Numbers 2) and 4) are simply water microscopes, which he mentions using in the Preface to Micrographia. Number 3) is a scotoscope, used for concentrating light rays onto a small area to provide illumination, and also described in the Preface. And number 1) was Hooke’s preferred choice of microscope slide, as he explains when recounting his replication of Antoni van Leeuwenhoek’s observations in the late 1670s. It is unlikely that someone in possession of mica, ornate microscopes, and with connections among the fellows of the Royal Society as well as the instrument makers of London, was unable to obtain prisms with which to make experiments.

What is more likely is that, having spent four years making microscopical observations, Hooke stumbled again and again upon the incidental production of colours by his instruments. Chromatic aberration was a well known problem in microscopes and telescopes, which would not be solved until Dollond’s innovations in the eighteenth century. But using muscovy glass for specimen slides, and a water globe for illuminating his subjects, exposed Hooke two forms of colour production others may not have noticed. What’s more, in his Preface Hooke provides not only a detailed drawing of his primary instrument, but instructions on how it is made, and other versions suitable for other situations. Hooke doesn’t seem to have thought of his microscope as a static, finished product. Rather, he used one instrumental set up to make observations of distant objects such as the moon, and another to view things nearby and in his control. Even this could vary depending on whether the subject was translucent or opaque, and on the amount of light required to illuminate it. He notes trialling lenses made not just of glass, but resin, gum, oil, salt, and arsenic. All of this points to a man very aware of the behaviour of light and the process of refraction by which objects are magnified, and who was able to alter his instruments for the best results.

Some features of his theory are better explained by noting this likely route to Hooke’s knowledge of light, but a perhaps more difficult historical question is raised. Why did he present his observations as a constructed, systematic theory of colours rather than simply part of a history, as Boyle had done the previous year? It is likely the answer has something to do with ambition and rhetoric, and the role both Hooke and the other Fellows thought Micrographia would play in the early days of the Society.

Kant on experiments, hypotheses, and principles in natural philosophy

Alberto Vanzo writes…

As we have often noted on this blog, early modern experimental philosophers typically praised observations and experiments, while rejecting natural-philosophical hypotheses and assumptions not derived from experience. Along similar lines, Larry Laudan claimed that aversion to the method of hypothesis characterized “most scientists and epistemologists” from the 1720s to the end of the eighteenth century. Laudan mentioned Kant as one of the authors for whom “the method of hypothesis is fraught with difficulties”.

In this post, I will sketch a different reading of Kant. I will suggest that Kant, alongisde other German thinkers like von Haller, is an exception to the anti-hypothetical trend of the eighteenth century. Kant held that natural philosophers should embrace experiments and observations, but they are also allowed to formulate hypotheses and to rely on certain non-empirical assumptions. They should develop fruitful relationships between experiments and observations on the one hand, (some) hypotheses and speculations on the other.

I will illustrate Kant’s position by commenting on a sentence from the Pragmatic Anthropology: when we perform experiments,

- we must always first presuppose something here (begin with a hypothesis) from which to begin our course of investigation, and this must come about as a result of principles. (Ak. 7:223)

1. “[W]e must always first presuppose something here (begin with a hypothesis)…”

“For to venture forth blindly, trusting good luck until one stumbles over a stone and finds a piece of ore and subsequently a lode as well, is indeed bad advice for inquiry”. Even if we tried to perform experiments in a theoretical void, our activity would still be influenced by hypotheses and expectations. “Every man who makes experiments first makes hypotheses, in that he believes that this or that experiment will have these consequences” (24:889).

Like British experimental philosophers, Kant acknowledges that hypotheses and preliminary judgements may be “mere chimeras” (24:888), “romances” (24:220), castles in the air, or “empty fictions” (24:746). Hypotheses, like castles in the air, are fictions, but not all fictions must be rejected. The power of imagination, kept “under the strict oversight of reason” (A770/B798), can give rise to useful “heuristic fictions” (24:262). What is important is to be ready to reject or modify our hypotheses in the light of experimental results, so as to get closer and closer to the truth.

2. “…and this must come about as a result of principles.”

What principles are involved in our natural-philosophical investigations? As is well known, Kant holds that nature is constrained by a set of principles that we can establish a priori, like the causal law. In what follows, I will focus on three other principles that guide our experimental activity. They are the principles of homogeneity, specification, and affinity.

- The principle of homogeneity states that “one should not multiply beginnings (principles) without necessity” (A652/B680). Kant takes it to mean that one must always search for higher genera for all the species that one knows. An example is the attempt to regard the distinction between acids and alkali “as merely a variety or varied expression of one and the same fundamental material” (A652-53/B680-81).

- The principle of specification prohibits one from assuming that there are lowest species, that is, species which cannot in turn have sub-species. This led, for instance, to the discovery “[t]hat there are absorbent earths of different species (chalky earths and muriatic earths)” (A657/B685).

- The principle of affinity derives from the combination of the principles of homogeneity and specification. It prompt us to look for intermediate specices between the species that we already know.

For Kant, the principles of homogeneity, specification, and affinity are not derived a posteriori from our experimental inquiries. They are a priori assumptions that guide them. We would not find higher genera, lower species, and intermediate species in the first place, unless we assumed that they exist and we tested that assumption with experiments and observations. For Kant, this is a non-empirical assumption that precedes and guides natural-philosophical inquiries. These do not unfold entirely a posteriori. They presuppose hypotheses and principles that are prior to experience and enable us to extend our knowledge of the world. Thus, rather than rejecting hypotheses and non-empirical assumptions as many experimental philosophers did, Kant holds that a guarded use of them is useful for our study of nature.

The Giant’s Shoulders Blog Carnival #41

Welcome to the 41st edition of The Giant’s Shoulders blog carnival, a monthly roundup of the best blog posts on the history of science. We had a lot of great submissions this month – organized below in a few handy categories below for your reading pleasure.

Tales from the (science) crypt

Quite a few submissions for this edition of the carnival dealt with topics from the weird/occult with a scientific take on it. Eric Michael Johnson in The Primate Diaries tells us about the first anecdotes of vampires and how “they tell an important story about how people understood natural events.” Eric also gives us a post (first published at archy) about Stalin and his alleged plan to create an army of ape-warriors. The post focuses on the ethics of such type of scientific experiments.

We also received two submissions on curious topics found in the Royal Society’s Philosophical Transactions. Emma Davidson writes in the blog of the Royal Society’s History of Science Centre about “spooky subjects” in the Philosophical Transactions. In the traditional way of the members of the Royal Society, Davidson gives us samples of their approaches to witchcraft and ghostly themes. The other post in this area comes from the BBC News Magazine and it shows curious entries in the Royal Society’s archive, among them canine blood transfusion and a 1665 article about “the view from the moon.” Fascinating!

Finally, over at the blog of the Philadelphia Area Center for History of Science Darin Hayton looks at a controversy regarding the number of witches that were executed.

Historical figures

We received a number of great posts about interesting historical figures. At Providentia, Romeo Vitelli puzzles over the suicide of Ludwig Boltzmann in 1906: a man who had so much to live for! Tim Jones at Zoonomia tells us a few things he gleaned from Sir David Attenborough’s Darwin Lecture 2011 about Alfred Russel Wallace (co-discoverer of natural selection). He describes how Darwin and Wallace “reached a gentlemanly solution with no ill feelings all round”. Stephen Curry at Reciprocal Space tells us about Benjamin Thomson (a.k.a. Count von Rumford), who led the revolution against Lavoisier’s caloric theory of heat. He describes Rumford as “not a man wracked by self-doubt”, who had the audacity to draw a very flattering analogy between himself and Newton! Michael Ryan at Paleoblog tells us about Giovanni Arduino, the father of Italian geology, who gave a clear paleontological interpretation of the age sequence of the fossil record. Over at the Royal Society Blog, Emily Roberts tells us about the 16th-Century forebears of Boyle, Wren and Newton: John Rastell, Thomas Digges, John Dee, and William Gilbert. Finally, at Art History Today, David Packwood offers us an interesting portrait of Leonardo da Vinci as artist and natural philosopher.

Astronomy and space travel, past and present

Over at the Provientia blog, Romeo Vitelli gives us a fascinating account of John Wilkins’ early plans (as early as in 1638!) for a spaceship designed to take us to the Moon: “a flying machine, designed like a sailing ship but with clockwork gears and a set of wings. The wings would be covered with swan or goose feathers and would be powered by an internal combustion engine using gunpowder.”

At Vintage Space, Asteitel tells us the story of the rise and fall of Pluto: how it was discovered, how its anomalies were identified, until the International Astronomical Union established that it is not a planet in 2006 – unless you are in Illinois, where Pluto is a planet by law.

Medicine

Syphilis was known as the morbus gallicus, but at Powered by Osteons, Kristina Killgrove tells us about newly discovered evidence for its presence in Roman Spain as early as the second or third century AD. “So did the Romans have syphilis? The jury’s still out, but I’m guessing there will be enough evidence soon for someone to add ‘insanity resulting from neurosyphilis’ to the list of crazy theories for why the Roman Empire fell.”

Moving to modern times, Jai Virdi explains how the aurist John Harrison Curtis used an instrument – the cephaloscope, on which he wrote a treatise in 1842 – to affirm his authority, as a symbol of skills and judgement. Speaking of authority, the Quack Doctor features an entertaining excerpt from a satire of itinerary eighteenth-century medical salesmen:

- Gentlemen, Because I present myself among you, I would not have you to think, I am any Upstart Glister-pipe Bum-peeping Apothecary; no, Gentlemen, I am no such person: I am a regular Physician, and have travelled most Kingdoms in the World, purely to do my Country good.

Geology

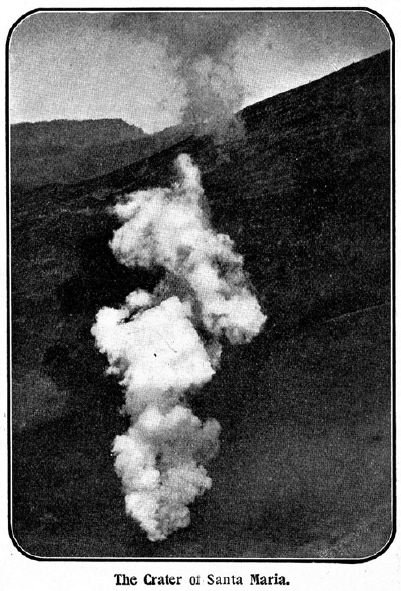

On the topic of geology, as well as the post on Giovanni Arduino, we received one from Jessica Ball at Magma cum Laude, where she discusses the 1902 eruption of Santa Maria. She looks at a particularly descriptive account of the eruption, explaining it in modern scientific terms. And David Bressan, over at History of Geology, tells us about the development of Ichnology (‘the examination of traces’), and the early forebears of this field – Leonardo da Vinci and Ulisse Aldrovandi – who drew some dangerous conclusions!

Exhibitions

We were pleased to find some blog posts about or inspired by current exhibitions. Jacy Young has an entry on a very interesting film archive on the History of the Human Sciences. Kris Coronado gives us an account of an impressive collection of books (and a meteorite!) displayed at Johns Hopkins, first editions of both of Newton’s most famous works among the books exhibited. Katy Barrett reminds us in her post how those of us involved in research projects tend to take our particular questions wherever we go, when she tells us how an exhibition at the British Museum got her thinking about longitude. Last but not least, Laura Massey gives us a very interesting post on the advances of cryptography brought about by the Shakespeare authorship issue, theme of an upcoming movie called Anonymous.

That’s all for this edition of the Carnival. Thanks to all the bloggers for providing so much interesting reading material and to you, reader, for stopping by. The next edition of the Carnival is still looking for a home. If you would like to volunteer as a host, get in touch with Thony C or with the Dr SkySkull. Nominations as usual by the 15th December either directly to the host or on the Carnival website.

Von Haller on hypotheses in natural philosophy

Alberto Vanzo writes…

Typically, the experimental philosophers on whom we focus in this blog promoted experiments and observations, while decrying hypotheses and system-building. This is the case for several experimental physicians, to some of whom we have devoted the last two posts. Their Swiss colleague Albrecht von Haller thought otherwise. He published an apology of hypotheses and systems in 1751.

Von Haller was a novelist, a poet, and an exceptionaly prolific writer on nearly all aspects of human knowledge. He is said to have contributed twelve thousand articles to the Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen. However, von Haller was mainly employed as an anatomist, physiologist, and naturalist. Like his Scottish colleague Monro I, he had studied in Leyden under Boerhaave. Having achieved Europe-wide fame for his physiological and botanical discoveries, von Haller was called by George II of England, prince-elector of Hanover, to occupy the inaugural chair of medicine, anatomy, botany and surgery at the newly founded University of Göttingen. Göttingen was under the strong influence of British culture throughout the eighteenth century and would later be the main centre of German experimental philosophers. While in Göttingen, von Haller was mainly engaged in his physiological and botanical studies, besides organizing an anatomical theatre, a botanical garden, and other similar institutions.

Haller’s essay, entitled “On the Usefulness of Hypotheses”, was first published as a premise to the German edition of Buffon’s Natural History. It was reprinted posthumously in 1787. Throughout these years, several authors in the German speaking-world endorsed Newton’s radically negative attitude towards hypotheses. For instance, few years after von Haller’s essay the physician Gerard van Swieten — also a pupil of Boerhaave — published a discourse on medicine in which he cried “may hypotheses be banned!”. And in the 1780s, when von Haller’s essay was being reprinted, the anthropologist Johann Karl Wezel proclaimed in broadly Newtonian spirit: “I only relate facts”.

Von Haller was aware of this anti-hypothetical fashion. He starts his essay by describing how naturalists had come to despise hypotheses. With the success of mathematical natural philosophy (the Newtonian form of experimental philosophy that had replaced Baconian natural histories), researchers started to rely (or at least, to claim that they were only relying) on what had been mathematically proven. This happened first in England with Newton, then in Holland with Boerhaave, then in Germany and France with Maupertuis and others.

For Haller, this was not a positive development. Peopled shifted from one excess, namely abusing of hypotheses, to an other, namely rejecting them altogether, while ignoring the virtuous middle way. Yet, while researchers were despising hypotheses, they were relying heavily on them:

- The great advantage of today’s higher mathematics, this dazzling art of measuring the unmeasurable, rests on a mere hypothesis. Newton, the destroyer of arbitrary opinions, was unable to avoid them completely. […] His universal matter, the medium of light, of sound, of the senses, of elasticity — was it not a hypothesis?

Von Haller makes other examples of natural-philosophical hypotheses, in order to highlight

- the true use of hypotheses. They are certainly not the truth, but they lead to it, and I say even more: humans have not found any way that is more successful in leading them to the truth [than hypotheses], and I cannot think of any inventor who did not make use of hypotheses.

What is this “true use of hypotheses”? It is their heuristic use. Hypotheses are claims to be tested by means of experiments and observations. Sets of hypotheses form large-scale systematic pictures that provide purpose and direction to our research. Think for instance of the heuristic value of the corpuscular hypothesis for the experimental activity of the early Royal Society (this is not von Haller’s example). Additionally, hypotheses make possible a public discussion of problems that scientists could not even mention if they were only allowed to talk about were facts, as some experimental philosophers hoped.

These experimental philosophers may reply to von Haller that they do not need to employ hypotheses to achieve those aims. All that is needed are queries. Von Haller would reply that queries are nothing else than hypotheses in disguise. “In fact, Hypotheses raise questions, whose answer we demand from experience, questions that we would not have raised if we did not formulate hypotheses”.

Von Haller was not the only author in the German-speaking world to provide a qualified defense of hypotheses. Christian Wolff before him and Immanuel Kant after him made similar points. However, von Haller was much more engaged in empirical research than either of them. His work seems to me to have been very much in the spirit of experimental philosophy. Finding such an explicit and detailed defense of hypotheses by such an author reminds us that the methodological views of early modern experimentalists were not monolithic and that, even in a strongly anti-hypothetical age, some authors were aware of the benefits of a careful use of hypotheses in the study of nature.

The Prehistory of Empiricism

Alberto Vanzo writes…

As some of you will know, I have claimed for a while that the distinction between empiricism and rationalism was first introduced by Kant in the Critique of Pure Reason. However, a quick search on Google Books reveals that there were many occurrences of “empiricism” and “rationalism” before Kant was even born. What is new about Kant’s use of these terms?

In this post I will survey early modern uses of “empiricism” and its cognates, “empiric” and “empirical”. I will argue that Kant’s new use of “empiricism” reflects a shift from the historical tradition of experimental philosophy to a new set of concerns.

Medical empiricism

Early modern authors often used “empiricism” and its cognates in medical contexts. Empirical physicians were said to depend “on experience without knowledge or art”. They did not have a good reputation. Shakespeare was expressing a common view when he wrote in All’s Well that Ends Well: “We must not corrupt our hope, To prostitute our past-cure malladie To empiricks”.

However, some defended empirical physicians. For instance, according to Johann Georg Zimmermann, the ancient physician Serapion of Alexandria was a good empiric. Why? Because he followed the method of experimental philosophy. He relied on experience and rejected idle hypotheses:

- Serapion and his followers rejected the inquiries of hidden causes and stuck to the visible ones […] So one can see that the founder of the sect of empirics had the noble purpose to band the love of hypotheses and useless quarrels from the medical art.

Political empiricism

Tetens wrote in 1777: “It has been asked in politics whether [politicians] should derive their maxims from the way the world goes, or whether they should derive them from rational insight.” Those who chose the first alternative were empirical politicians. Like empirical physicians, they were usually the target of criticism. Several writers throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth century agreed that true politicians could not be “blind empirics”.

Who opposed empirical politicians? It was the dogmatic or — as a review from 1797 called them, speculative politicians. Speculative politicians relied on “philosophical hypotheses and unilateral [i.e., insufficient] observations”, from which they rashly derived general conclusions. Once again, empirical politicians and their adversaries are implicitly identified with experimental and speculative philosophers.

Empirical people

The term “empiric” was also used in a general sense to refer to people who “owe their cognition to the senses” and “steer their actions on the basis of experience“. Leibniz famously said that we are empirics in three quarters of our actions. Bacon called empirics those who perform experiment after experiment without ever reflecting on the causes and principles that govern what they experience.

At least two of Kant’s German predecessors, Baumgarten and Mayer, coined disciplines called “empiric” that deal with the origin of our cognitions from experience or introspection. Additionally, two German historians identified an “empirical philosophy” that they contrasted with “scientific philosophy”.

Kant: what’s new in his usage?

Kant built on these linguistic uses when he introduced a new notion of empiricism:

- Like the authors referred to by some historians, Kant’s empiricists are philosophers.

- Like empirical physicians, empirical politicians, and empirical people, Kant’s empiricists rely entirely on experience.

However, Kant’s empiricism is not a generic reliance on experience, nor is it primarily related to the rejection of hypotheses and speculative reasonings. Kant’s empiricists advocate specific epistemological views (taking “epistemology” in a broad sense), that is, views on the origins and foundations of our knowledge. They deny that we can have any substantive a priori knowledge and they claim that all of our concepts derive from experience.

What is new in Kant’s notion of empiricism is the shift from a generic reference to experience and to the methodological issues that were distinctive of early modern x-phi, to broadly epistemological issues. To be sure, Kant was not concerned with epistemology for its own sake. He aimed to answer ontological and moral questions. Nevertheless, the epistemological issues that Kant’s new notion of empiricism focuses on are the issues that post-Kantian histories of philosophy, based on the dichotomy of empiricism and rationalism, would place at the centre of their narratives.

Do you think this is persuasive? I am collecting early modern uses of “empiricism” and “rationalism”, so if you know some interesting occurrence, please let me know. Also, if you are familiar with methods for performing quantitative analyses of early modern corpora, could you get in touch? I would appreciate your advice.

On the Origins of a Historiographical Paradigm

Alberto Vanzo writes…

- It came to pass that the earth was without form, and void, and darkness covered the face of the earth. And the creator saw that the darkness was evil, and he spoke out in the darkness, saying “Let there be light” and there was light, and he called the light “Renaissance”. But still the creator was not pleased, for there remained darkness, and hence he took from the Renaissance a rib, with which to fashion greater light. But the strain of his power broke the rib, and there did grow up two false lights, one Bacon, whose name meanteh “Father of the British Empiricists”, and one Descartes, whose name meaneth “Father of the Continental Rationalists”. […]

And thus it was that Bacon begat Hobbes, and Hobbes begat Locke, and Locke begat Berkeley, and Berkeley begat Hume. And thus it was that Descartes begat Spinoza, and Spinoza begat Leibniz, and Leibniz begat Wolff. And then it was that there arose the great sage of Königsberg, the great Immanuel, Immanuel Kant, who, though neither empiricist nor rationalist, was like unto both. […]

And this too the creator saw, and he saw that it was good […]

In this parody, David Fate Norton has summarized a familiar account of the history of early modern philosophy — an account based on the antagonism of empiricism and rationalism. It has dominated histories of philosophy for most of the twentieth century, including Russell’s and Copleston’s histories.

In an earlier post, I argued that the distinction between empiricism and rationalism was fleshed out into a fully-fledged history of philosophy by the Kantian historian Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann at the beginning of the nineteenth century. (To be sure, two other historians made use of the distinction roughly at the same time as Tennemann, but his hisory was by far the most influential.)

The question I’d like to discuss in this post is: how do we get from Tennemann to Copleston and Russell? At some point between the 1820s and 1940s, the account of early modern philosophy that can be found in Tennemann must have been exported from Germany to the English-speaking world. When and how did this happen?

Here are three hypotheses.

1. British philosophers around the 1830s?

The first English translation of Tennemann’s Manual was published in 1832. At that time, three British philosophers were interested in the history of philosophy: William Hamilton, Samuel Coleridge, and Dugald Stewart. None of them produced any substantial writing that made use of the rationalism-empiricism distinction. Thomas Morell had published in 1827 a History of Philosophy that would be reprinted many times, but he did not distinguish early modern philosophers into empiricists and rationalists. He split them into four groups:

- sensualists like Bacon, Hobbes, and Locke;

- idealists like Descartes, Spinoza, and Berkeley;

- sceptics like Hume;

- and mystics like Jacobi.

Morell’s notion of “sensualism” is similar to our notion of empiricism, but he does not group Locke, Berkeley, and Hume together as empiricists or sensualists. Nor does he create a rationalist category to contrast with sensualism.

2. English histories of philosophy in the second half of the nineteenth century?

Some of these were based on the distinction between empiricism and rationalism or similar distinctions, but many were not. For instance, the history written by F.D. Maurice followed a strictly chronological order, without grouping philosophers into movements. German Hegelians and British Idealists grouped together Descartes, Malebranche, and Spinoza, but not Leibniz. They claimed that these philosophers were criticized by two groups of thinkers: realists like Locke and Hume, but not Berkeley, and idealists like Leibniz and Berkeley. These distinctions cut across the traditional groupings of empiricists and rationalists.

3. Textbook writers at the turn of the twentieth century?

It was between 1895 and 1915 that the account of early modern thought based on the empiricism-rationalism distinction became standard in the English-speaking world. It can be found in many new introductions to philosophy, histories of philosophy, and lecture syllabi.

It is unclear to me why the standard account become standard between 1895 and 1915. I suspect that the answer has to do with two factors:

The first is the institutionalization of the study of early modern philosophy. The classificatory schema based on the contrast of empiricism and rationalism was simpler than the others and well suited for teaching.

The second factor (highlighted by Alex Klein) is the rise of philosopher-psychologists like William James. By grouping together Locke, Berkeley, and Hume as empiricists, the standard accounts of early modern philosophy provided a distinguished ancestry for the growing number of American philosophers and psychologists who, under the James’ influence, called themselves empiricists.

I’m keen to hear if you think that these explanations are persuasive and if you have any other suggestions.