Who invented the Experimental Philosophy?

Peter Anstey writes…

Sometimes the question ‘Who invented X?’ has no determinate answer, in spite of claims of particular individuals. One thinks of questions like ‘Who invented the internet?’ and the various dubious claims to this honour. Christoph Lüthy has argued quite convincingly that ‘the microscope was never invented’ (Early Science and Medicine, 1, 1996, p. 2). I suggest that the same probably goes for the experimental philosophy: there is no single person or group of people who created it, rather it somehow ‘emerged’ in Europe sometime between the death of Francis Bacon in 1626 and the founding of the Royal Society in 1660. One place to look for answers is to trace the early uses of the term ‘experimental philosophy’.

Here is the evidence that I am aware of for the emergence of the term ‘experimental philosophy’ in early modern England. The first English work to use the term ‘experimental philosophy’ according to EEBO was Robert Boyle’s Spring of the Air in 1660. Interestingly, the term philosophia experimentalis had already appeared in the title of Nicola Cabeo’s Latin commentary on Aristotle’s Meteorology of 1646 and Boyle cites Cabeo’s book twice in Spring of the Air. The first English book to use the term in its title was Abraham Cowley’s A Proposition for the Advancement of Experimental Philosophy of 1661. From then on, however, books about experimental philosophy start to roll off the presses of England. Boyle’s Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy and Henry Power’s Experimental Philosophy, both published in 1663, got the ball rolling. (Incidentally, Cabeo’s book was reprinted in Rome in 1686 under the title Philosophia experimentalis.) As for manuscript sources, the earliest use of the term ‘experimental philosophy’ that I have found is in Samuel Hartlib’s Ephemerides in 1635.

Another place to look for evidence for the inventor of the experimental philosophy is in discussions of natural philosophy and of experiment. It appears that Francis Bacon never used the term ‘experimental philosophy’, but he did develop a conception of experientia literata (learned experience), which might be thought to be a precursor of the experimental philosophy. This appears in Book 5 of his De augmentis scientiarum of 1623, where it is distinguished from interpretatio naturae (interpretation of nature). The experientia literata is a method of discovery proceeding from one experiment to another, whereas interpretatio naturae involves the transition from experiments to theory. But this doesn’t resemble the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy very closely. For example, the experimental philosophy was, on the whole, opposed to speculation and hypotheses and there is no sense of opposition or tension in Bacon’s distinction.

Furthermore, a distinction between operative (or practical) and speculative philosophy was commonplace in scholastic divisions of knowledge in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, and this, no doubt provided the basic dichotomy on which the experimental/speculative distinction was based. But the operative/speculative distinction doesn’t map very well onto the experimental/speculative distinction, not least because by ‘operative sciences’ the scholastics meant ethics, politics and oeconomy (that is, management of society) and not observation and experiment.

Who invented the experimental philosophy? I don’t think that there is a determinate answer to this question, but I’m happy to be corrected and am keen for suggestions as to where to look for more evidence.

Locke’s Master-Builders were Experimental Philosophers

Peter Anstey says…

In one of the great statements of philosophical humility the English philosopher John Locke characterised his aims for the Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690) in the following terms:

- The Commonwealth of Learning, is not at this time without Master-Builders, whose mighty Designs, in advancing the Sciences, will leave lasting Monuments to the Admiration of Posterity; But every one must not hope to be a Boyle, or a Sydenham; and in an age that produces such Masters, as the Great – Huygenius, and the incomparable Mr. Newton, with some other of that Strain; ’tis Ambition enough to be employed as an Under-Labourer in clearing Ground a little, and removing some of the Rubbish, that lies in the way to Knowledge (Essay, ‘Epistle to the Reader’).

Locke regarded his project as the work of an under-labourer, sweeping away rubbish so that the ‘big guns’ could continue their work. But what is it that unites Boyle, Sydenham, Huygens and Newton as Master-Builders? It can’t be the fact that they are all British, because Huygens was Dutch. It can’t be the fact that they were all friends of Locke, for when Locke penned these words he almost certainly had not even met Isaac Newton. Nor can it be the fact that they were all eminent natural philosophers, after all, Thomas Sydenham was a physician.

In my book John Locke and Natural Philosophy, I contend that what they had in common was that they all were proponents or practitioners of the new experimental philosophy and that it was this that led Locke to group them together. In the case of Boyle, the situation is straightforward: he was the experimental philosopher par excellence. In the case of Newton, Locke had recently reviewed his Principia and mentions this ‘incomparable book’, endorsing its method in later editions of the Essay itself. Interestingly, in his review Locke focuses on Newton’s arguments against Descartes’ vortex theory of planetary motions, which had come to be regarded as an archetypal form of speculative philosophy.

In the case of Huygens, little is known of his relations with Locke, but he was a promoter of the method of natural history and he remained the leading experimental natural philosopher in the Parisian Académie. In the case of Sydenham, it was his methodology that Locke admired and, especially those features of his method that were characteristic of the experimental philosophy. Here is what Locke says of Sydenham’s method to Thomas Molyneux:

- I hope the age has many who will follow [Sydenham’s] example, and by the way of accurate practical observation, as he has so happily begun, enlarge the history of diseases, and improve the art of physick, and not by speculative hypotheses fill the world with useless, tho’ pleasing visions (1 Nov. 1692, Correspondence, 4, p. 563).

Note the references to ‘accurate practical observation’, the decrying of ‘speculative hypotheses’ and the endorsement of the natural ‘history of diseases’ – all leading doctrines of the experimental philosophy in the late seventeenth century. So, even though Sydenham was a physician, he could still practise medicine according to the new method of the experimental philosophy. In fact, many in Locke’s day regarded natural philosophy and medicine as forming a seamless whole in so far as they shared a common method. It should be hardly surprising to find that Locke held this view, for he too was a physician.

If it is this common methodology that unites Locke’s four heroes then we are entitled to say ‘Locke’s Master-Builders were experimental philosophers’. I challenge readers to come up with a better explanation of Locke’s choice of these four Master-Builders.

Two Forms of Natural History

Peter Anstey writes…

There were two forms of natural history in the early modern period: traditional natural history and Baconian natural history. The distinction between them becomes clear in the light of the development of the experimental philosophy in the mid-17th century. Unfortunately, however, this distinction is almost always elided in the secondary literature on natural history.

Traditional natural history, deriving from Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides, had flourished in the late Renaissance. It involved the mapping of nature through the classification of plants and animals and the assembling of information about their uses and habits. This traditional natural history continued throughout the 17th century and reached its zenith in the 18th century in the work of the likes of Carl Linnaeus. But this was neither the only form of natural history, nor, for that matter, was it the most important form for the experimental philosophers. Let me explain.

The experimental philosophy of the seventeenth century developed as a method of knowledge acquisition in natural philosophy. However, unlike the division between science and philosophy today, in the early modern period natural philosophy and philosophy were not regarded as discrete disciplinary domains. Natural philosophy was thought to be the philosophy of nature, rather than, say, the philosophy of morality or metaphysics. Thus Descartes’ Principles of Philosophy are principles of natural philosophy and this work presents his mature natural philosophical system.

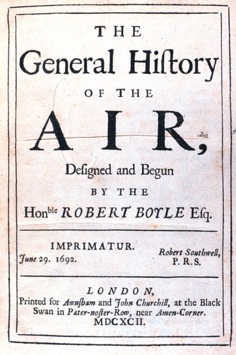

Robert Boyle's General History of the Air

The experimental philosophy was initially developed and applied in the study of nature and only later was it applied more broadly to the other parts of philosophy. The first ‘version’ of the experimental philosophy was the Baconian method of natural history. This was inspired by Francis Bacon’s grand scheme for the renovation of knowledge of nature and in particular his novel approach to natural history.

The Baconian method involved the assembling of vast amounts of data about particular substances, qualities or states of bodies. In this way it was far broader in its scope than traditional natural history. To be sure, it included facts about generations––that is animal, plant and insect species-–but it included much more, such as histories of cold, of the air, of electrostatic phenomena and of fluidity and solidity, etc. According to the Baconian method, once all of the facts were collected they were to be ordered and structured in such a way as to facilitate theoretical, or speculative, reflection upon the phenomenon at hand. Thus, once all the facts about, say, human blood or the air, were gathered, then the natural philosopher would be in a position to develop a true and accurate philosophy of the blood or air.

It was this method that was developed in a detailed and sophisticated way by the early Royal Society and which became popular across Europe in the second half of the 17th century. This Baconian natural history encompassed traditional natural history and as a result traditional natural history flourished under its aegis. But, the Baconian form of natural history was short-lived: it was in serious decline in the 1690s and all but disappeared in the first decades of the 18th century. All the while traditional natural history was going from strength to strength and was soon to become one of the most important branches of 18th century science.

The reasons for the decline of Baconian natural history need not detain us here, but the reason for the eliding of the distinction between it and traditional natural history is of great importance. I contend that scholars have failed to distinguish between the two because of their failure to appreciate the nature and significance of the experimental philosophy in general. When we view early modern natural history through the lens of the experimental philosophy the distinction between the two forms of natural history becomes clear. This is another reason why, as I claimed in an earlier post, ESP is best!

On the Proliferation of Empiricisms

Peter Anstey writes…

One sign that a historiographical category no longer earns its keep is that it needs to be redefined in each new context of use. Another is that it leads to a proliferation of taxonomies of meaning. Such is the case with the term ’empiricism’. I have commented in a previous post that this term is becoming increasingly difficult to pin down: that Don Garrett gives us 5 empiricisms; Michael Ayers gives us 2; Jonathan Lowe gives us 3 and so on. In his recent post on the New APPS Blog Eric Schliesser gives us 4 and refers us to a recent article by Charles Wolfe which provides 3. If we throw into the mix Feyerabend’s 3 and Ernan McMullin’s 2 forms of ‘classical empiricism’ and allow for overlap, we have around 15 different forms of empiricism! And this is only a sampling of the field. It’s a field that is too crowded for anyone’s liking and provides one of the main arguments for letting go of the whole Kantian/post-Kantian historiographical category and for exploring the experimental/speculative distinction as a positive alternative.

The claim here is not that each of these 15 or so empiricisms is without value in so far as they might give us some insight into a particular thinker or trend within early modern thought. It is rather that the term ’empiricism’ is being called upon to do too much work to the point that its semantic domain is too fluid for it to have a determinate meaning. It is simply bad history to flog a term this hard.

This is where the experimental/speculative distinction can help. The fact that it is a historical distinction, that is easy to locate in early modern natural philosophers and philosophers alike, makes it easy to track. Restricting ourselves to Anglophone works, searches in EEBO and ECCO for ’empiricism’ (in any of the 15 senses) and ‘Rationalism’ yield very meagre results, but similar searches using ‘experimental’, ‘experimental philosophy’, ‘speculative’, ‘speculative philosophy’ and their cognates (e.g. ‘speculation’) are enormously fruitful.

What we claim is that it is now time to work through early modern thought using these terms and this distinction and to determine what the results are. We do not claim that ‘experimental philosophy’ has one determinate meaning (see my last post on Baconian vs Newtonian Experimental Philosophy). So it’s not as if we ourselves might never face a proliferation problem (though so far it seems to us that the usage of the terms is relatively consistent). It’s rather that the heuristic value of such a research program is enormous, whereas the rationalism/empiricism distinction is nearing its ‘use-by date’. We are not in competition with those who hang on to rationalism and empiricism. Rather we have a complementary and, in our view, far more promising research program.

Baconian versus Newtonian experimental philosophy

Peter Anstey writes…

Eric Schliesser’s comments about the utility of the experimental/speculative distinction, provide an opportunity for me to lay out a distinction that is absolutely central to our project. But let’s hear from Eric first: I quote from his blog post on It’s Only a Theory:

- It ignores at least one other group of philosophers, namely those that believed in (mathematical) theory mediated measurement. I am thinking of Galileo, Huygens, and Newton, among the best known. These are not best described as experimental, although all were accomplished experimentalists (and Newton’s Optics is often assimilated to experimental traditions), but their work has very different character from say, Bacon or Boyle. (They are also not best described as speculative, because all three practiced a self-restraint on published speculation.) Certainly after the Principia this approach created standing challenge to all other forms of philosophizing. So the Otago framework will run into big trouble in 18th century.

We’ve already shown that, in fact, the terminology of the experimental philosophy is very prevalent in the 18th century and, moreover, that the experimental philosophy was extended beyond natural philosophy into moral philosophy and even aesthetics. See, for example, the works of George Turnbull which are a good example of experimental moral philosophy.

But the important issue Eric raises has to do with those who practised ‘theory mediated measurement’ such as Galileo, Huygens and Newton. What our research has shown is that the experimental philosophy was practised in two quite different ways. Up until the 1690s, Boyle, Hooke and the early Royal Society practised experimental philosophy according to the method of Baconian natural history. However, from the last decade of the seventeenth century Newton’s new mathematical natural philosophical method came to be seen as the preferred method of experimental philosophy. The Baconian natural history program started to run out of steam in the 1690s and it soon came to be replaced by the Newtonian method. This is, in fact, the explanation of Newton’s common refrain ‘Natural philosophy is not natural history’. And Newton himself had a large hand in the demise of the Baconian approach to experimental philosophy both through criticism and through his own positive alternative. Far from providing an exception to our framework, Newton, the self-confessed experimental philosopher, is one of the central players!

ESP is best

Peter Anstey writes…

There are two ways to carve up 17th and 18th century philosophy: the traditional way is to divide it into rationalist versus empiricist philosophy (REP); a new way is to divide it into experimental versus speculative philosophy (ESP). We argue that the ESP way is far better than the traditional terms of reference.

Let’s start the comparison by pointing out the fact that the ESP distinction provided the actual historical terms of reference that many philosophers and natural philosophers used from the 1660s until late into the 18th century. There are literally scores of books from the period that use these terms and deploy this distinction (They are used by Boyle, Hooke, Sprat, Glanvill, Cavendish, Locke and Newton). By contrast, the terms ‘Rationalism’ and ‘Empiricism’ (and their non-English cognates) were introduced by Kant and his followers in the late 18th century. One can find very occasional uses of the terms in the earlier period, but they have completely different meanings. For example, ‘empiricism’ in Johnson’s Dictionary (1768) means ‘Dependence on experience without knowledge or art; quackery’.

Second, on the standard view, REP is largely about epistemology, that is the origins of ideas and sources of knowledge. The REP view has it that rationalists claimed that there are innate ideas and that these are the foundations of knowledge: the empiricists claimed that all ideas originate in the senses and that knowledge is built upon experience and not innate ideas or principles. By contrast, ESP is largely about methodology, about how to proceed in acquiring knowledge, especially knowledge of nature. It includes questions about the sources of knowledge and ideas, but it also includes views on the nature of hypotheses, principles, theory, mathematics, experiment and natural history.

So ESP has more explanatory range than REP and allows a more nuanced understanding of individual philosophical positions and debates. One important example is Newton’s rejection of hypotheses. This is very nicely explained by ESP, but is largely irrelevant to REP and has therefore posed a problem for scholars who approach Newton from the REP framework.

Third, you’ll notice that I highlighted ‘standard view’ above. This is because nowadays it is pretty difficult to settle on exactly what ‘Empiricism’ and ‘Rationalism’ mean. The Hume scholar Don Garrett reckons that there are 5 types of Empiricism. The Locke scholars Jonathan Lowe and Michael Ayers give us 3 and 2 types respectively. Paul Feyerabend reckoned that there were 3 types and Ernan McMullin has a few more. This proliferation of empiricisms is an indicator that the term no longer earns its keep.

By contrast, the term ‘experimental philosophy’, while it admits of some latitude of application, its widespread use by the philosophers themselves means that it’s pretty easy to work out whether someone is an experimental philosopher or not and whether they are sympathetic to it.

Fourth and finally, there’s the issue of demarcation. According to REP the leading empiricists are normally thought to be Locke, Berkeley and Hume and the leading rationalists are Descartes, Leibniz and Spinoza. But even this is often contested: Des Clarke has Descartes as an empiricist; Richard Aaron had Locke as a rationalist; Nicholas Rescher has Leibniz as an empiricist! And where does Robert Boyle, the archetypal experimental philosopher sit? He promoted observation by the senses, but he was partial to innate ideas. ESP provides a far more natural line of demarcation and one that explains this vacillation on the part of modern scholars.

All in all ESP is better. So what should we do with the Rationalism and Empiricism distinction? Are there any good reasons to retain it?

Is x-phi old hat?

Peter Anstey writes…

The term ‘experimental philosophy’ has been around for a very long time. It began to appear in the titles of books in English in the early 1660s!

Early modern x-phi is not the same as contemporary x-phi, but we think that there are important and interesting connections between the two.

Steve Stich, a contemporary experimental philosopher

Early modern x-phi began as an approach to the study of nature that emphasised observation and experiment as the primary source of knowledge about the world and opposed the use of speculation from first principles and the use of hypotheses. It was a broad movement in natural philosophy (the science of nature) that soon spread to medicine, the study of the understanding, and, in the eighteenth century, to moral philosophy and aesthetics. (It is to be differentiated from the post-Kantian category of Empiricism. We’ll publish a post on this soon.)

Contemporary x-phi is a philosophical methodology that applies both scientific experiments and the tools of analytic philosophy to philosophical problems. Its main domains of application are the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of perception, and moral philosophy.

Early modern x-phi and contemporary x-phi have at least one very important thing in common. The early modern experimental philosophers were fed up with speculations and theories about the world that were based on untested or untreatable principles: contemporary experimental philosophers are also tired of philosophical arguments about, say perception, that are based on premises on people’s intuitions that are either untested or in some cases have been shown to be false by scientific experiments.

One of the first experimental philosophers, Robert Boyle

But there are also important differences between the two. For instance, early modern x-phi was an all-encompassing approach to the study of nature, a scientific method if you will, whereas contemporary x-phi is more modest in its aspirations (though some see it as supplanting traditional philosophy).

Furthermore, early modern x-phi went through various incarnations because key methodological notions such as hypothesis, experiment and confirmation were stilly being clarified. For example, for its first four decades the early moderns thought that experimental philosophy should be done using the method of Baconian natural history. The success of Newton’s Principia changed all that. By contrast, contemporary x-phi has a sophisticated and robust set of methodological practices and principles on which to proceed.

We are no experts in the new experimental philosophy, but as we explore aspects of its old incarnation in the next posts, we’d be delighted to hear your views on how it relates to its new homonym.