A new Hume find

Peter Anstey writes…

While the ‘Experimental Philosophy: Old and New’ exhibition was under construction, the Special Collections Librarian at Otago, Dr Donald Kerr, happened to notice that the copy of George Berkeley’s An Essay Towards a New Theory of Vision (2nd edn, 1709) that we were about to display, had the bookplate of David Hume Esquire. It has long been known that this book was in the library of the philosopher David Hume’s nephew Baron David Hume, but until now its whereabouts have been unknown. We are very pleased to announce, therefore, that it is in the Hewitson Library of Knox College at the University of Otago, New Zealand (for full bibliographic details see the online exhibition).

The question naturally arises: did the book belong to the philosopher or the Baron? What complicates matters is that David Hume the philosopher left his library to his nephew of the same name and that the latter also used a David Hume bookplate.

Now the David Hume bookplate exists in two states, A and B. They are easily distinguished because State A has a more elongated calligraphic hood on the second stem of the letter ‘H’ than that of State B. Brian Hillyard and David Fate Norton have pointed out (The Book Collector, 40 [1991], 539–45) that all of the thirteen items that they have examined with State A are on laid paper and are in books that predate the death of David Hume the philosopher. This is not the case for books bearing the State B bookplate. They propose the plausible hypothesis that all books bearing the bookplate in State A belonged to Hume the philosopher. Happily, we can report that the bookplate that here at Otago is State A on laid paper. It is almost certain, therefore, that this copy of George Berkeley’s New Theory of Vision belonged to the philosopher David Hume.

The provenance of the book provides important additional evidence that Hume was familiar with Berkeley’s writings, something that was famously denied by the historian of philosophy Richard Popkin in 1959. Popkin claimed that ‘there is no actual evidence that Hume was seriously concerned about Berkeley’s views’. He was subsequently proven wrong and retracted his claim. However, until now there has been no concrete evidence that Hume owned a copy of a work by Berkeley, let alone one as important as the New Theory of Vision.

This volume came into the possession of the Hewitson Library in 1948. Its title page bears a stamp from the ‘Presbyterian Church of Otago & Southland Theological Library, Dunedin’. So far attempts to ascertain which other books were in this theological library and when and how it arrived in New Zealand have proven fruitless. (Though the copy of William Whiston’s A New Theory of the Earth, 1722 on display bears the same stamp.) If any reader can supply further leads on these matters we would be most grateful. Meanwhile please take time to examine the images of the bookplate and title page, which are included in our online exhibition available here.

Experimental Philosophy: Old and New

Over the last few months, we have been working with Dr Donald Kerr, the Special Collections Librarian at the University of Otago, to prepare a rare book exhibition on the history of experimental philosophy. We have brought together classic works of the past and cutting-edge books of the present, to illustrate the theme of experimental philosophy as it was understood and practised 350 years ago and as it is understood today.

- Our exhibition, ‘Experimental Philosophy: Old and New’, was launched a few weeks ago, to coincide with the annual conference of the Australasian Association of Philosophy (AAP). It will run until 23 September 2011, so if you are coming to Dunedin, be sure to stop by and see it.

For those who cannot come to Dunedin, we are thrilled to announce the launch of the online version of our exhibition. Notable items on display include a second edition of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1713), Francis Bacon’s Of the Advancement Learning (1640), poet Abraham Cowley’s ‘A Proposition for the Advancement of Experimental Philosophy’ (1668), and an exciting new discovery* concerning the philosopher David Hume!

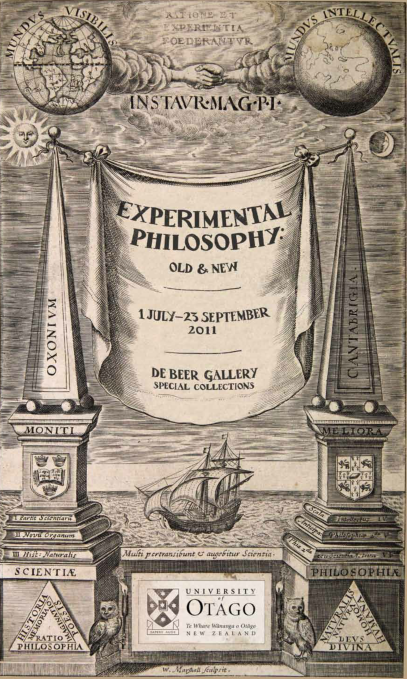

A couple of months ago, I requested your help: we needed an image for our exhibition poster. We received some excellent feedback – so thank you everyone! We eventually settled on a modified version of the frontispiece to 1640 translation of Bacon’s ‘De Augmentis Scientiarum’.

We hope you enjoy our exhibition!

* On Monday Peter Anstey will tell us all about this new discovery regarding Hume.

Experiment, Culture, and the History of Philosophy

One tremendous change over the past 27 years, which makes this redux not simply a repetition, has been the appearance, and reappearance, of experimental philosophy: that is, the emergence of experimental philosophy as a defining feature of the non-historical wing of the discipline, as well as a crucial focus of study (thanks in no small part to the work of the Otago group) for scholars studying the history of early modern philosophy.

A question of central methodological importance for the historian of philosophy concerns the appropriate relationship between the aspects of philosophy’s past that a scholar takes on, on the one hand, and on the other the current agenda of non-historical philosophy. Recently, in the results of a query launched by Mark Lance at the NewAPPS blog, my own deep worry about the state of the discipline was confirmed: a good many non-historian philosophers believe that, at the end of the day, history-of-philosophy scholarship should make itself relevant to the cluster of questions currently being investigated in philosophy. I could not disagree more strongly. To riff on John F. Kennedy’s famous line, I believe that we should not be asking what the history of philosophy can do for us, but rather what we can do for the history of philosophy. That is, we should be attempting to do justice to past thinkers by carefully reconstructing their own world of concerns. In doing so, we shall often have to move beyond the boundaries of what we consider philosophy (and even of what they considered philosophy).

I have argued in many fora that we should respect the historical usage of the term ‘philosophy’. Some have objected that it is a semantic issue –as in, a mere semantic issue– what might have been called by a certain name in another era. What is important, they say, is whether the activity so-called in fact has any continuity with what we are doing when we do philosophy. To some today, the discontinuity seems most evident when we consider early modern experimental philosophy. There simply is no meaningful sense, they maintain, in which we can think of meteorology as a proper part of philosophy, even if this is how it was conceived in the history of natural philosophy from Aristotle through (at least) Boyle.

We might suppose that this discontinuity is bridged to some extent by the recent appearance of an activity going by the name of ‘experimental philosophy’, but of course the scope of ‘experimental’ was very different for, e.g., Margaret Cavendish than for Joshua Knobe. Nonetheless, it is certainly worthwhile to reflect on what the 17th- and 21st-century versions of experimental philosophy share, and also on what they might someday share. For now, the new experimental philosophy sees itself as having common cause principally with experimental psychology. As some philosophers sympathetic to x-phi have argued, however, the concept of ‘experiment’ could be extended much further than has been done so far. Jesse Prinz, in particular, has suggested that ‘experiment’ could be understood broadly to include what we think of as ‘experience’: thereby reuniting it with its lexical ancestor, and also reconciling with the intuitions that x-phi initially came out against.

If experiment is (re-)broadened to include experience, then willy-nilly we arrive in a situation for philosophy in which, in effect, any source of information may be deemed of interest. Such a situation, I think, is one in which history-of-philosophy scholarship could thrive. It is one in which, moreover, this branch of scholarship would find common cause with historical anthropology. It might even open itself up to non-textual sources of information (e.g., instrument design, seed collections). The text would be dethroned as the exclusive source of information about what was motivating thinkers to come up with the ideas they had.

For a long time it has seemed unnecessary to historians of philosophy to move beyond texts, since philosophy is about ideas, and where else but in texts are ideas encoded? Certainly, texts are a useful source of ideas from the past, but seed collections and instrument design are also, so to speak, fossils of past intentions, and there is no reason why they should not complement texts of philosophy, just as the layout of graves complements hieroglyphic texts in an Egyptologist’s effort to reconstruct ancient Egyptian ideas about the afterlife.

But we tend to think of an Egyptologist’s work as having to do with culture, while we do not, today, think of historians of philosophy as specialists in culture at all. Historians of philosophy are supposed to be engaging with more-or-less timeless ideas, which are not supposed to be bound by the parameters of the culture inhabited by the thinker who had them. But let’s be serious. Is, say, Leibniz’s account of the fate of the soul of a dog after death (that is, shrinking down into a microscopic organic body and floating around in the air and in the scum of ponds for all eternity) really any more viable a candidate for the true theory of life after death than the account offered in The Egyptian Book of the Dead? I don’t believe so, and when I read Leibniz’s account it is not because I am considering adopting this account myself. It is because I am interested in the range of ways people in different times and places have conceptualized the irresolvable problem of the fate of the soul. I specialize in 17th-century Christian European approaches to this mystery, but I could just as easily have been an Egyptologist.

To acknowledge that we are studying culture –not all culture, but a particular manifestation of a certain culture: the European educated elite, which leaves its traces in texts, but not only in texts– is to make a move that is exactly parallel to the one practitioners of non-historical experimental philosophy are currently making relative to the discipline that houses them. Current x-phi is putting philosophy back into culture by empirically studying the culture-bound nature of intuitions, rather than resting content with the intuitions of self-appointed experts in intuition-having. This is a welcome development, but I believe it must be seen as just one small part of a broader project of re-embedding philosophy in culture, and I believe historians of philosophy have a particularly important role to play in this project. Philosophy in history is philosophy in culture.

Even if Boyle and Cavendish meant something different by ‘experimental philosophy’ than Knobe and Nichols do, to take an interest in Boyle and Cavendish’s conception of philosophy as extending to experimental science is to contribute in a specialized way, I believe, to the overall aim of current x-phi, which is to study how people in different times and places actually think. In pursuing this aim, current x-phi practitioners have found common cause with experimental psychologists. The parallel interdisciplinary move for the historian of philosophy should be one that brings us closer to the work of historical anthropologists.

Newton’s 4th Rule for Natural Philosophy

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In book three of the 3rd edition of Principia, Newton added a fourth rule for the study of natural philosophy:

- In experimental philosophy, propositions gathered from phenomena by induction should be considered either exactly or very nearly true notwithstanding any contrary hypotheses, until yet other phenomena make such propositions either more exact or liable to exceptions.

- This rule should be followed so that arguments based on induction be not be nullified by hypotheses.

Arguably this is the most important of Newton’s four rules, and it certainly sparked a lot of discussion at our departmental seminar last week. Let us see what insights we can glean from it.

Rule 4 breaks down neatly into three parts. I shall address each part in turn.

1. Propositions (acquired from the phenomena by induction) should be regarded as true or very nearly true.

While the term ‘phenomenon’ usually refers to a single occurrence or fact, Newton uses the term to refer to a generalisation from observed physical properties. For example, Phenomenon 1, Book 3:

- The circumjovial planets [or satellites of Jupiter], by radii drawn to the centre of Jupiter; describe areas proportional to the times, and their periodic times – the fixed stars being at rest – are as the 3/2 powers of their distances from that centre.

- This is established from astronomical observations…

Newton uses the term ‘proposition’ in a mathematical sense to mean a formal statement of a theorem or an operation to be completed. Thus, he further identifies propositions as either theorems or problems. Propositions are distinguished from axioms in that propositions are not self-evident. Rather, they are deduced from phenomena (with the help of definitions and axioms) and are demonstrated by experiment. For example, Proposition 1, Theorem 1, Book 3:

- The forces by which the circumjovial planets [or satellites of Jupiter] are continually drawn away from rectilinear motions and are maintained in their respective orbits are directed to the centre of Jupiter and are inversely as the squares of the distances of their places from that centre.

- The first part of the proposition is evident from phen. 1 and from prop. 2 or prop. 3 of book 1, and the second part from phen. 1 and from corol. 6 to prop. 4 of book 1.

Newton appears to be using ‘induction’ in a very loose sense to mean any kind of argument that goes beyond what is stated in the premises. As I noted above, his phenomena are generalisations from a limited number of observed cases, so his natural philosophical reasoning is inductive from the bottom up. Newton recognises that this necessary inductive step introduces the same uncertainty that accompanies any inductive generalisation: the possibility that there is a refuting instance that hasn’t been observed yet.

Despite this necessary uncertainty, in the absence of refuting instances, Newton tells us to regard these propositions as true or very nearly true. It is important to note that he is not telling us that these propositions are true, simply that we should act as though they are. Newton is simply saying that if our best theory fits the available data, then we should regard it as true until proven otherwise.

2. Hypotheses cannot refute or alter those propositions.

In a previous post I argued that, in his early optical papers, Newton was working with a clear distinction between theory and hypothesis. In Principia Newton is working with a similar distinction between propositions and hypotheses. Propositions make claims about observable, measurable physical properties, whereas hypotheses make claims about unobservable, unmeasurable causes or natures of things. Thus, propositions are on epistemically surer footing than hypotheses, because they are grounded on what we can directly experience. When faced with a disagreement between a hypothesis and a proposition, we should modify the hypothesis to fit the proposition, and not vice versa. Newton explains this idea in a letter to Cotes:

- But to admitt of such Hypotheses in opposition to rational Propositions founded upon Phaenomena by Induction is to destroy all arguments taken from Phaenomena by Induction & all Principles founded upon such arguments.

3. New phenomena may refute those propositions by contradicting them, or alter those propositions by making them more precise.

This final point highlights the a posteriori justification of Newton’s theories. In Principia, two methods of testing can be seen. The first involves straightforward prediction-testing. The second is a more sophisticated method, which involves accounting for discrepancies between ideal and actual motions by a series of steps that increase the complexity of the model.

In short, Rule 4 tells us to prioritise propositions over hypotheses, and experiment over speculation. These are familiar and enduring themes in Newton’s work, which reflect his commitment to experimental philosophy. Rule 4 echoes the remarks made by Newton in a letter to Oldenburg almost 54 years earlier, when he wrote:

- …I could wish all objections were suspended, taken from Hypotheses or any other Heads then these two; Of showing the insufficiency of experiments to determin these Queries or prove any other parts of my Theory, by assigning the flaws & defects in my Conclusions drawn from them; Or of producing other Experiments wch directly contradict me…

Leibniz: An Experimental Philosopher?

Alberto Vanzo writes…

In an essay that he published anonymously, Newton used the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy to attack Leibniz. Newton wrote: “The Philosophy which Mr. Newton in his Principles and Optiques has pursued is Experimental.” Newton went on claiming that Leibniz, instead, “is taken up with Hypotheses, and propounds them, not to be examined by experiments, but to be believed without Examination.”

Leibniz did not accept being classed as a speculative armchair philosopher. He retorted: “I am strongly in favour of the experimental philosophy, but M. Newton is departing very far from it”.

In this post, I will discuss what Leibniz’s professed sympathy for experimental philosophy amounts to. Was Newton right in depicting him as a foe of experimental philosophy?

To answer this question, let us consider four typical features of early modern experimental philosophers:

- self-descriptions: experimental philosophers typically called themselves such. At the very least, they professed their sympathy towards experimental philosophy.

- friends and foes: experimental philosophers saw themselves as part of a tradition whose “patriarch” was Bacon and whose sworn enemy was Cartesian natural philosophy.

- method:experimental philosophers put forward a two-stage model of natural philosophical inquiry: first, collect data by means of experiments and observations; second, build theories on the basis of them. In general, experimental philosophers emphasized the a posteriori origins of our knowledge of nature and they were wary of a priori reasonings.

- rhetoric: in the jargon of experimental philosophers, the terms “experiments” and “observations” are good, “hypotheses” and “speculations” are bad. They were often described as fictions, romances, or castles in the air.

Did Leibniz have the four typical features of experimental philosophers?

First, he declared his sympathy for experimental philosophy in passage quoted at the beginning of this post.

Second, Leibniz had the same friends and foes of experimental philosophers. He praised Bacon for ably introducing “the art of experimenting”. Speaking of Robert Boyle’s air pump experiments, he called him “the highest of men”. He also criticized Descartes in the same terms as British philosophers:

- if Descartes had relied less on his imaginary hypotheses and had been more attached to experience, I believe that his physics would have been worth following […] (Letter to C. Philipp, 1679)

Third, the natural-philosophical method of the mature Leibniz displays many affinities with the method of experimental philosophers. To know nature, a “catalogue of experiments is to be compiled” [source]. We must write Baconian natural histories. Then we should “infer a maximum from experience before giving ourselves a freer way to hypotheses” (letter to P.A. Michelotti, 1715). This sounds like the two-stage method that experimental philosophers advocated: first, collect data; second, theorize on the basis of the data.

Fourth, Leibniz embraces the rhetoric of experimental philosophers, but only in part. He places great importance on experiments and observations. However, he does not criticize hypotheses, speculations, or demonstrative reasonings from first principles as such. This is because demonstrative, a priori reasonings play an important role in Leibniz’s natural philosophy.

Leibniz thinks that we can prove some general truths about the natural world a priori: for instance, the non-existence of atoms and the law of equality of cause and effect. More importantly, a priori reasonings are necessary to justify our inductive practices.

When experimental natural philosophers make inductions, they presuppose the truth of certain principles, like the principle of the uniformity of nature: “if the cause is the same or similar in all cases, the effect will be the same or similar in all”. Why should we take this and similar principles to be true? Leibniz notes:

- [I]f these helping propositions, too, were derived from induction, they would need new helping propositions, and so on to infinity, and moral certainty would never be attained. [source]

There is the danger of an infinite regress. Leibniz avoided it by claiming that the assumption of the uniformity of nature is warranted by a priori arguments. These prove that the world God created obeys to simple and uniform natural laws.

In conclusion, Leibniz really was, as he wrote, “strongly in favour of the experimental philosophy”. However, he aimed to combine it with a set of a priori, speculative reasonings. These enable us to prove some truths on the constitution of the natural world and justify our inductive practices. Leibniz’s reflections are best seen not as examples of experimental or speculative natural philosophy, but as eclectic attempts to combine the best features of both approaches. In his own words, Leibniz intended “to unite in a happy wedding theoreticians and observers so as to improve on incomplete and particular elements of knowledge” (Grundriss eines Bedenckens […], 1669-1670).

Experimenting with taste and the rules of art

Juan Gomez writes…

In 1958 Ralph Cohen published a paper titled David Hume’s Experimental Method and the Theory of Taste, where he argues that the main contribution of Hume’s essay Of the Standard of Taste (OST) was his “insistence on method, on the introduction of fact and experience to the problem of taste.” I agree with Cohen, but I think his overall interpretation of the essay on taste still falls short of giving a proper account of Hume’s theory of taste. I’d like to build on Cohen’s statement and support it with the help of the framework we are proposing in this project, where Early Modern Experimental Philosophy plays a prominent role.

Hume’s essay on taste begins with a description of the paradox of taste: It is obvious that taste varies among individuals, but it is also obvious that some judgments of taste are universally agreed upon (Hume’s example is that everyone admits that John Milton is a better writer than John Ogilby). Hume relies on the experimental method to solve the paradox. From the initial paragraphs of the essay we can see that Hume is calling for an approach to the appreciation of art works that resembles the experimental method of natural philosophy. If we are to solve the problem of taste, we need to focus on particular instances, and from them we can deduce the ‘rules of composition’ or ‘rules of art.’ This is achieved the same way natural philosophy observes the phenomena to deduce the laws of nature. The main reason for this focus on particular over the general is that Hume thinks that in matters of taste, as well as in morality founded on sentiment, “The difference among men is really greater than at first sight appear.” Although everyone approves of justice and prudence in general, when it comes to particular instances we find that “this seeming unanimity vanishes.”

The objects we appreciate as works of art, according to Hume, possess qualities that “are calculated to please, and others to displease.” The essay on taste applies the experimental method to particular experiences with artworks, and after a number of these experiences we can identify those qualities which comprise the rules of art:

- “It is evident, that none of the rules of composition are fixed by reasonings a priori, or can be esteemed abstract conclusions of the understanding, from comparing those habitudes and relations of ideas, which are eternal and immutable. Their foundation is the same with that of all the practical sciences, experience; nor are they anything but general observations, concerning what has been universally found to please in all countries and in all ages.” (OST, 210)

We need to approach matters of taste the same way we approach matters of natural philosophy: by focusing on the particular phenomena, which in this case are our interactions with works of art. Hume’s essay on taste works as a guide for the appreciation of art. It is not, as most of the scholars who comment on Hume’s essay believe, a method just for critics to apply, but rather a guide for any individual to engage in an aesthetic experience. Hume tells us that one of the aims of the essay is “to mingle some light of the understanding with the feelings of sentiment,” so the faulty of delicacy of taste takes a central role in Hume’s theory. Such faculty can and should be improved and developed, which leads us to think that the process Hume describes is not only for the critics but open to anyone.

- “But though there be naturally a very wide difference in point of delicacy between one person and another, nothing tends further to encrease and improve this talent,than practice in a particular art, and the frequent survey or contemplation of a particular species of beauty.” (OST, 220)

If we want to derive the most pleasure out of our aesthetic experiences we need to experiment with works of art in order to develop our delicacy of taste.

If we accept this reading of Hume’s essay we can shed light on its purpose. It was not the attempt to establish a standard of taste, but rather a guide for engaging with works of art and to have discussions regarding matters of taste.

Early modern x-phi: a genre free zone

Peter Anstey writes…

One feature of early modern experimental philosophy that has been brought home to us as we have prepared the exhibition entitled ‘Experimental Philosophy: Old and New’ (soon to appear online) is the broad range of disciplinary domains in which the experimental philosophy was applied in the 17th and 18th centuries. Some of the works on display are books from what we now call the history of science, some are works in the history of medicine, some are works of literature, others are works in moral philosophy, and yet they all have the unifying thread of being related in some way to the experimental philosophy.

Two lessons can be drawn from this. First – and this is a simple point that may not be immediately obvious – there is no distinct genre of experimental philosophical writing. Senac’s Treatise on the Structure of the Heart is just as much a work of experimental philosophy as Newton’s Principia or Hume’s Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals. To be sure, if one turns to the works from the 1660s to the 1690s written after the method of Baconian natural history, one can find a fairly well-defined genre. But, as we have already argued on this blog, this approach to the experimental philosophy was short-lived and by no means exhausts the works from those decades that employed the new experimental method.

Second, disciplinary boundaries in the 17th and 18th centuries were quite different from those of today. The experimental philosophy emerged in natural philosophy in the 1650s and early 1660s and was quickly applied to medicine, which was widely regarded as continuous with natural philosophy. By the 1670s it was being applied to the study of the understanding in France by Jean-Baptiste du Hamel and later by John Locke. Then from the 1720s and ’30s it began to be applied in moral philosophy and aesthetics. But the salient point here is that in the early modern period there was no clear demarcation between natural philosophy and philosophy as there is today between science and philosophy. Thus Robert Boyle was called ‘the English Philosopher’ and yet today he is remembered as a great scientist. This is one of the most important differences between early modern x-phi and the contemporary phenomenon: early modern x-phi was endorsed and applied across a broad range of disciplines, whereas contemporary x-phi is a methodological stance within philosophy itself.

What is it then that makes an early modern book a work of experimental philosophy? There are at least three qualities each of which is sufficient to qualify a book as a work of experimental philosophy:

- an explicit endorsement of the experimental philosophy and its salient doctrines (such as an emphasis on the acquisition of knowledge by observation and experiment, opposition to speculative philosophy);

- an explicit application of the general method of the experimental philosophy;

- acknowledgment by others that a book is a work of experimental philosophy.

Now, some of the books in the exhibition are precursors to the emergence of the experimental philosophy (such as Bacon’s Sylva sylvarum). Some of them are comments on the experimental philosophy by sympathetic observers (Sprat’s History of the Royal Society), and others poke fun at the new experimental approach (Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels). But this still leaves a large number of very diverse works, which qualify as works of experimental philosophy. Early modern x-phi is a genre free zone.

Early Modern Philosophy at the AAP

The Annual Conference of the Australasian Association of Philosophy will start in 10 days and the abstracts have just been published. We were very pleased to see that there are plenty of papers on early modern philosophy. We are re-posting the abstracts below.

As you will see, Juan, Kirsten, Peter, and I are presenting papers on early modern x-phi and the origins of empiricism. Come and say hi if you’re attending the conference. If you aren’t, but would like to read our papers, let us know and we’ll be happy to send you a draft. Our email addresses are listed here. We’d love to hear your feedback.

Peter Anstey, The Origins of Early Modern Experimental Philosophy

This paper investigates the origins of the distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy (ESP) in the mid-seventeenth century. It argues that there is a significant prehistory to the distinction in the analogous division between operative and speculative philosophy, which is commonly found in late scholastic philosophy and can be traced back via Aquinas to Aristotle. It is argued, however, the ESP is discontinuous with this operative/speculative distinction in a number of important respects. For example, the latter pertains to philosophy in general and not to natural philosophy in particular. Moreover, in the late Renaissance operative philosophy included ethics, politics and oeconomy and not observation and experiment – the things which came to be considered constitutive of the experimental philosophy. It is also argued that Francis Bacon’s mature division of the sciences, which includes a distinction in natural philosophy between the operative and the speculative, is too dissimilar from the ESP to have been an adumbration of this later distinction. No conclusion is drawn as to when exactly the ESP emerged, but a series of important developments that led to its distinctive character are surveyed.

Russell Blackford, Back to Locke: Freedom of Religion and the Secular State

For Locke, religious persecution was the problem – and a secular state apparatus was the solution. Locke argued that there were independent reasons for the state to confine its attention to “”civil interests”” or interests in “”the things of this world””. If it did so, it would not to motivated to impose a favoured religion or to persecute disfavoured ones. Taken to its logical conclusion, this approach has implications that Locke would have found unpalatable. We, however, need not hesitate to accept them.

Michael Couch, Hume’s Philosophy of Education

Hume has rarely been considered a contributor to the philosophy of education, which is unsurprising as he did not write a dedicated treastise nor make large specific comment, and so educators and philosophers have focused their attention elsewhere. However, I argue that a more careful reading of his works reveals that education is a significant concern, specificially of enriching the minds of particular people. I argue that his educational ideas occupy an important, although not major, place in his writings, and also an important place in the history of ideas as Hume fills a gap after Locke, and provides the framework for the much more educationally influential Bentham and Mill.

Gillian Crozier, Feyerabend on Newton: A defense of Newton’s empiricist method

In “Classical Empiricism,” Paul Feyerabend draws an analogy between Isaac Newton’s empiricist methodology and the Protestant faith’s primary tenet sola scriptura. He argues that the former – which dictates that ‘experience’ or the ‘book of nature’ is the sole justified basis for all knowledge of the external world – and the latter – which dictates that the sole justified basis for all religious understanding is Scripture – are equally vacuous. Feyerabend contends that Newton’s empiricism, which postures that experience is the sole legitimate foundation of scientific beliefs, serves to disguise supplementary background assumptions that are not observer-neutral but are steeped in tradition, dogma, and socio-cultural factors. He focuses on Newton’s treatment of perturbations in the Moon’s orbit, arguing that this typifies how Newton supports his theory by cherry-picking illustrations and pruning them of anomalies through the incorporation of ad hoc assumptions. We defend Newton’s notion of empirical success, arguing that Newton’s treatment of the variational inequality in the lunar orbit significantly adds to the empirical success a rival hypothesis would have to overcome.

Simon Duffy, The ‘Vindication’ of Leibniz’s Account of the Differential. A Response to Somers-Hall

In a recent article in Continental Philosophy Review, entitled ‘Hegel and Deleuze on the metaphysical interpretation of the calculus,’ Henry Somers-Hall claims that ‘the Leibnizian interpretation of the calculus, which relies on infinitely small quantities is rejected by Deleuze’(Somers-Hall 2010, 567). It is important to clarify that this claim does not entail the rejection of Leibniz’s infinitesimal, which Leibniz considered to be a useful fiction, and which continues to play a part in Deleuze’s account of the metaphysics of the calculus. In order to further clarify the terms of this debate, I will take up two further issues with Somers-Hall’s presentation of Deleuze’s account of the calculus. The first is with the way that recent work on Deleuze’s account of the calculus is reduced to what Somers-Hall refers to as ‘modern interpretations of the calculus,’ by which he means set-theoretical accounts. The second is that this reduction by Somers-Hall of ‘modern interpretations of the calculus’ to set-theoretical accounts means that his presentation of Deleuze’s account of the calculus is only partial, and the partial character of his presentation leads him to make a number of unnecessary presumptions about the presentation of Deleuze’s account of the ‘metaphysics of the calculus’.

Sandra Field, Spinoza and Radical Democracy

Antonio Negri’s radical democratic interpretation of Benedictus de Spinoza’s political philosophy has received much attention in recent years. Its central contention is that Spinoza considers the democratic multitude to have an inherent ethical power capable of grounding a just politics. In this paper, I argue to the contrary that such an interpretation gets Spinoza back to front: the ethical power of the multitude is the result of a just and fair political institutional order, not its cause. The consequences of my argument extend beyond Spinoza studies. For Spinoza gives a compelling argument for his rejection of a politics relying on the virtue of a mass subject; for him, such a politics substitutes moral posturing for understanding, and fails to grasp the determinate causes of the pathologies of human social order. Radical democrats hoping to achieve effective change would do well to lay aside a romanticised notion of the multitude and pay attention to the more mundane question of institutional design.

Juan Gomez, Hume’s Four Dissertations: Revisiting the Essay on Taste

Sixteen years ago a number of papers and discussions considering Hume’s essay on taste emerged in various journals. They deal with a number of issues that have been commonly thought to arise from the argument of the essay: some authors take Hume to be proposing two different standards of taste, other think that his argument is circular, and other focus on the role the standard and the critics play in Hume’s theory. I believe that all the issues that have been identified arise from a reading of the essay that takes it out of its context of publication, and mistakes Hume’s purpose in the essay. In this paper I want to propose an interpretation of the essay on taste that takes into account two key aspects: the unity of the dissertations that were published along with the essay on taste in 1757, under the title of Four Dissertations, and Hume’s commitment to the Experimental Philosophy of the early modern period. I believe that these two contextual aspects of the essay provide a reading of the essay on taste that besides solving the identified issues, gives us a good idea of its aim and purposes.

Jack MacIntosh, Models and Methods in the Early Modern Period: 4 case studies

In this paper I consider the various roles of models in early modern natural philosophy by looking at four central cases: Marten on the germ theory of disease. Descartes, Boyle and Hobbes on the spring of the air; The calorific atomists, Digby, Galileo, et al. versus the kinetic theorists such as Boyle on heat and cold; and Descartes, Boyle and Hooke on perception. Did models in the early modern period have explanatory power? Were they taken literally? Did they have a heuristic function? Unsurprisingly, perhaps, consideration of these four cases (along with a brief look at some others) leads to the conclusion that the answer to each of these questions is yes, no, or sometimes, depending on the model, and the modeller, in question. I consider briefly the relations among these different uses of models, and the role that such models played in the methodology of the ‘new philosophy.’ Alan Gabbey has suggested an interesting threefold distinction among explanatory types in the early modern period, and I consider, briefly, the way in which his classification scheme interacts with the one these cases suggest.

Kari Refsdal, Kant on Rational Agency as Free Agency

Kant argued for a close relationship between rational, moral, and free agency. Moral agency is explained in terms of rational and free agency. Many critics have objected that Kant’s view makes it inconceivable how we could freely act against the moral law – i.e., how we could freely act immorally. But of course we can! Henry Allison interprets Kant so as to make his view compatible with our freedom to violate the moral law. In this talk, I shall argue that Allison’s interpretation is anachronistic. Allison’s distinction between freedom as spontaneity and freedom as autonomy superimposes on Kant a contemporary conception of the person. Thus, Allison does not succeed in explaining how an agent can freely act against the moral law within a Kantian framework.

Alberto Vanzo, Rationalism and Empiricism in the Historiography of Early Modern Philosophy

According to standard histories of philosophy, the early modern period was dominated by the struggle between Descartes’, Spinoza’s, and Leibniz’s Continental Rationalism and Locke’s, Berkeley’s, and Hume’s British Empiricism. The paper traces the origins of this account of early modern philosophy and questions the assumptions underlying it.

Kirsten Walsh, Structural Realism, the Law-Constitutive Approach and Newton’s Epistemic Asymmetry

In his famous pronouncement, Hypotheses non fingo, Newton reveals a distinctive feature of his methodology: namely, he has asymmetrical epistemic commitments. He prioritises theories over hypotheses, physical properties over the nature of phenomena, and laws over matter. What do Newton’s epistemic commitments tell us about his ontological commitments? I examine two possible interpretations of Newton’s epistemic asymmetry: Worrall’s Structural Realism and Brading’s Law-Constitutive Approach. I argue that, while both interpretations provide useful insights into Newton’s ontological commitment to theories, physical properties and laws, only Brading’s interpretation sheds light on Newton’s ontological commitment to hypotheses, nature and matter.

Eric Watkins on Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth-Century Germany

Eric Watkins writes…

Having commented on two of Alberto Vanzo’s papers at the symposium recently held in Otago, I am happy to post an abbreviated version of my comments. The basic topic of Alberto’s papers is the extent to which one can see evidence of the experimental – speculative philosophy distinction (ESD) in two different periods in Germany, one from the 1720s through the 1740s, when Wolff was a dominant figure, and then another from the mid 1770s through the 1790s, when Tetens, Lossius, Feder, Kant, and Reinhold were all active. Alberto argues that though Wolff was aware of the works of many of the proponents of experimental philosophy and emphasized the importance of basing at least some principles on experience and experiments, he is not a pure advocate of either experimental or speculative philosophy. He then argues that some of the later figures, specifically Tetens, Lossius, Feder and various popular philosophers, undertook projects that could potentially be aligned with ESD, while others, such as Reinhold and later German Idealists, consciously rejected it, opting for the rationalism-empiricism distinction (RED) instead, which was better suited to their own agenda as well as to that of their German Idealist successors. As a result, Alberto concludes that ESD was an option available to many German thinkers, but that experimental philosophy was not a dominant intellectual movement, as it was in England and elsewhere.

I am in basic agreement with Alberto’s main claims, but I’d like to supplement the account he offers just a bit with a broader historical perspective. Two points about Wolff. First, when Wolff tries to address how the historical knowledge relates to the philosophical knowledge, which can be fully a priori, it is unclear how his account is supposed to go. As Alberto points out, Wolff thinks that data collection and theory building are interdependent, but he also thinks that we can have a priori knowledge. It’s simply not clear how these two positions are really consistent and Wolff does not, to my mind, ever address the issue clearly enough. So I am inclined to think that Wolff is actually ambiguous on a point that lies at the very heart of ESD.

Second, though Wolff was certainly a dominant figure in Germany, he is of course also not the only person of note. For one, throughout the course of the 18th century, experimental disciplines became much more widespread in Germany. So, in charting the shape and scope of ESD at the time, it would be useful to see what conceptions of knowledge and scientific methodology university professors in physics, physiology, botany, and chemistry had, if any. For another, after the resurrection of the Prussian Academy of Sciences by Frederick the Great in 1740, a number of very accomplished figures with reputations of European-wide stature, such as Leonhard Euler, Maupertuis, and Voltaire, came to ply their trade in Berlin. Virtually all of them were quite interested in experimental disciplines and several were extremely hostile towards Wolff. It would therefore be worth considering the full range of their activities to get a sense of their views on ESD.

Let me now turn to the later time period. As Alberto argued, Kant isn’t exactly the right figure to look to for the origin of the RED. Kant does not typically contrast empiricism with rationalism. Instead, when it comes to question of method and the proper use of reason, Kant’s clearest statements in the Doctrine of Method are that the fundamental views are that of dogmatism (Leibniz), skepticism (Hume), indifferentism (popular philosophers), and finally the critique of pure reason, positions that do not line up neatly with either RED or ESD.

However, it would be hasty to infer that there is no significant element of ESD in Kant. Kant dedicates the Critique of Pure Reason to Bacon, an inspiration to many of the British experimentalists. More importantly, one should keep in mind whom Kant is attacking in the first Critique, namely proponents of pure reason who use reason independently of the deliverances of the senses in their speculative endeavors. In many of these instances, the term “speculative” is synonymous with “theoretical” and is contrasted with “practical”. However, in many others Kant is indicating a use of reason that is independent of what is given through our senses, and on that issue, it is a major thrust of Kant’s entire Critical project to show that the purely speculative use of reason (pure reason) cannot deliver knowledge. In this sense, his basic project reveals fundamental similarities with experimental philosophers.

Now the British experimental philosophers would presumably object to synthetic a priori knowledge on the grounds that this is precisely the kind of philosophical speculation that one ought to avoid. But Kant would respond that he is attempting to show that experiments in particular, and experience in general, have substantive rational presuppositions, a possibility that cannot be dismissed out of hand, given its intimate connection to what the experimental philosophers hold dear. This is one of the novel and unexpected twists that make Kant’s position so interesting. So one could incorporate Kant into the ESD narrative by arguing that he is trying to save the spirit of the experimentalists against those who are overly enamored with speculation while still allowing for rational elements. On this account, then, Kant would be responding directly to the ESD, namely by trying to save it, albeit in an extremely abstract and fundamental way that original proponents of the view could never have anticipated.

Tim Mehigan on ‘Empiricism vs Rationalism: Kant, Reinhold, and Tennemann’

Tim Mehigan writes…

Alberto Vanzo presented two papers for discussion at the recent Otago symposium on early modern experimental philosophy. There are two conclusions in the first paper (“Experimental Philosophy in Eighteenth Century Germany” [on which we’ll publish Eric Watkins’ comments next Monday]) that are important for the second paper: one, that experimental philosophy, as “observational philosophy”, was replaced in German historiography by the term “empiricism” (this occurred sometime before 1796 as a passage from an essay by Christian Garve indicates); two, as experimental/observational philosophy waned, so the historiographical distinction between rationalism and empiricism (RED) waxed. While the reasons for the waxing are not completely clear, there appear to be two ways of imagining how it occurred. The first view holds that Kant himself was responsible for legislating the RED into existence. The second argues that the distinction was not authorized by Kant but arose as a result of the way his philosophy was interpreted and explained by later Kantians such as Reinhold and Tennemann. Both explanations are considered and evaluated in Vanzo’s second paper “Empiricism vs. Rationalism.”

So this is what’s at stake: Vanzo needs to show how the RED can be read into Kant’s first Critique, even if it is not expressly established as a formal distinction on which other parts of the CPR depend. Given the strategy alluded to above – that Kant introduces a distinction under the guise of different terminology – Vanzo is obliged to consider whether we encounter a “mapping” problem when Kant’s contrasts are seen in the context of the RED. He immediately concedes that there is indeed such a mapping problem (as Gary Banham had noted here). The RED is introduced in two places in the CPR – the Antinomies of Pure Reason and the History of Pure Reason. In the first case, Kant contrasts empiricism with dogmatism (not rationalism), and in the second case, Kant contrasts empiricism with “noologism” (not rationalism). The question is: whether RED can “map onto” either or both of these contrasts and thus indicate compellingly that Kant operated with the RED in mind?

As it turns out, the occurrence of the RED in the History of Pure Reason is more readily answered than in the Antinomies. Vanzo establishes both that the contrast of “empiricism” and “noologism” in the History of Pure Reason can be regarded as a version of the RED and that the contrast established here was to become a standard part of the histories of early modern philosophy. The argument in the Antinomies follows a more circuitous route. Vanzo cannot directly show that “dogmatism” and “rationalism” are interchangeable terms, all the more so since Kant’s purpose in the Antinomies is to show that neither dogmatism nor empiricism on its own is able to offer satisfactory proofs of key statements about the world. So both dogmatism and empiricism come up short, and Kant, as a later self-identifying rationalist, is clearly not about to subscribe to the dogmatic variant of metaphysical rationalism. So a problem of mapping does appear here, and it is the more serious one for the RED distinction.

Was the RED introduced by Kant? Vanzo’s final answer is, “not really”. Kant does not have the “epistemological bias” in regard to the RED, i.e. he does not overestimate the importance of the RED on epistemological grounds. Neither does Kant have the “Kantian bias”, according to which the RED is important for his project in the Critique of Pure Reason. Kant, finally, does not have the “classificatory bias” which classifies all philosophers prior to Kant into either empiricist or rationalist camps. When we consider the later Kantians, the picture is quite different. Both Reinhold and Tennemann are said to have the epistemological, the Kantian and the classificatory biases. Reinhold, I believe, did not initially have the classificatory bias, as it is not clearly in evidence in his first major work, the Essay on a New Theory of the Human Capacity for Representation (1789). By the early 1790s, however, as Vanzo shows, Reinhold appears to have derived a historiographical framework based on the RED. Reinhold’s framework appears to have been important for philosophers such as Tennemann, who by the late 1790s had begun to craft a “methodologically sophisticated history of early modern philosophy” in which the RED is amply applied to individual philosophers and where Kant takes his place as the author who successfully overcame the limits of these two schools.

In sum, Vanzo’s case for the establishment of the RED in Germany appears to ascribe great importance to the manner in which Kantian philosophy was received from the mid 1780s until the mid 1790s and how it was laid out against a background of historiographical assumptions. As happens so often, the background was to become foreground for a few brief years, and when it did so under Reinhold’s pen – this is the likely conclusion – the historiography became more important than the philosophy. Fortunately this situation has reversed itself and Kant’s philosophy has become a far more open proposition than it was taken to be in those years. This openness, in turn, makes room for different conceptualizations of the early modern period.