Harry Potter and the TERFS: fans and feminists take on the British-colonial hate economy

A post written by Gini Jory, based on an ANTH424 assignment.

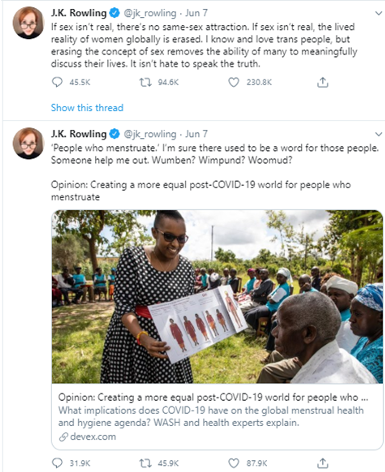

In June this year, at the beginning of pride month and during global BLM protests, JK Rowling disappointed her fans yet again by outing herself as a TERF- a trans exclusionary radical feminist. She posted a tweet mocking an article about ‘people who menstruate’ saying: “I’m sure there used to be a word for those people. Someone help me out. Wumben? Wimpund? Woomud?”[1] Online audiences pointed out this was anti-trans, as not all women menstruate and some men do. Others noted this as the latest in a line of anti-trans tweets Rowling had recently published.

The beginning of JK Rowling’s anti-trans tweet tirade, mocking the term “people who menstruate” and talking about the importance of biological sex. From https://twitter.com/jk_rowling

In response, as well as follow-up tweets, she published a defensive 3600 word essay to her website saying she “knows and loves trans people” but doesn’t want them to invalidate her lived experience as a woman, and doesn’t want them in women-only spaces where women should feel safe.[2] Unfortunately for transgender people, this hate is nothing new, and is increasingly common, particularly in the UK. This transphobia has very real consequences, with high numbers of attempted suicide and hate crimes that can and do lead to death. In 2019, 331 trans people were killed globally.[3] This is due to systemic hate – as this blog explores, using Sarah Ahmed’s idea of hate ‘economies’ to explore the links between seemingly innocuous online comments, and a longer history of violence of both literal and representational forms.

A quick background to TERF Ideology

The phrase TERF -trans exclusionary radical

feminist- has come to designate all feminists who oppose trans rights and inclusion in the feminist community. While originally intended as a descriptor, it has been seen as a slur by some it is applied to.[4]

Anti-trans sentiments in feminist communities have been around since second wave feminism in the 1970s. The stance now referred to as TERF has been attributed (not singularly, but perhaps as the best known example) to the 1979 book The Transsexual Empire by Janice Raymond, who stated that gender is an expression of biological sex, which is chromosomally dependant. She stressed the impossibility of changing chromosomal sex, and therefore gender and sex are decided at birth and cannot change. Because of this, Raymond views male-to-female transition as an act of the male patriarchy, meaning that in her view, trans women are not and can not ever be ‘real’ women.[5]

This position has been reinforced by trans exclusionary feminist academics, while trans activists and scholars note the impact of this publication in feminist circles. And this perspective has certainly created a divide, with many feminists, particularly in the UK, now framing trans rights as being in direct conflict with women’s rights. To trans exclusionary feminists, trans men are women and trans women are still men, and are therefore invaders in women’s spaces.

Transphobia in British feminist communities: a legacy of colonialism

TERF ideology is extremely prolific in the UK. This appears to be for several reasons; While other countries such as America have experienced mass movements over the last 30 years surrounding globalisation, police brutality, race, gender and class, the UK has experienced far less of these protests. This means middle and upper-class white feminists have not had their privilege questioned by black and indigenous feminists as their American counterparts have, and so have retained their credibility and influence.

Feminists hold an anti-TERF sign, outside a Labour Party event in which TERFS were participating, in London, March 2020. Attribution: Charles Hutchins. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Feminism_is_intersectional_No_Terfs_No_Swerfs_(49643458203).jpg

There is also a long history of British feminism intertwining with Colonialism. The British Empire enforced heterosexuality and the gender binary on indigenous communities at a policy level, constructing the racial ‘other’ as not only fundamentally inferior, but also as a sexual menace because of their gender variance from perceived ‘biological realities’. It is this enforcement of the binary that Trans exclusionary feminists continue to impose. It should be noted that Irish feminists have rejected British TERF ideologies specifically because of their experiences under British Colonialism.[6]

This transphobia, a hatred and fear of trans bodies and their variations to the gender norm have been expressed in many ways. Notably there have been debates and protests over the use of single-sex spaces – women’s bathrooms and the Ponds in London.[7] (Trans people’s use of single-sex spaces is legally protected under the 2010 Equality Act.) These incidents come back to the perspective that trans women are still men, and are therefore forcing themselves on women in these spaces, an act which some TERFs have likened to rape. This violent language creates fear and paranoia, making trans people something “other” to be afraid of. This has led to sensationalised cases of ‘gender fraud’ in the media, where people have been convicted of hiding their gender from partners.

The power of paper and screen

I would argue that mainstream media in general is responsible in part for this narrative. As discussed in the 2020 documentary Disclosure, which is about trans people in media, films about trans people have historically shown the partner discovering their lover has the ‘wrong’ genitals and breaking down, even vomiting in reaction.[8] This validates TERF perspectives of trans women having something to hide, of lying and being predatory villains, in the acceptable mainstream.

In 2018 TERFs got more airtime than ever as the Gender Recognition Act of 2004 was reviewed. At the time, the GRA required a years long medicalised process to ‘prove’ a person was trans. Recommended reforms encompassed inclusion of trans youth, no medical diagnosis and the ability to self -identify through a more streamlined process.[9] High-ranking TERF Journalists such as Suzanne More and Julie Burchill wrote anti-trans pieces which spread throughout the UK media. These focused on the ‘taking away’ of women’s rights and the fear that violent men would be able to simply say they were a woman and be legally allowed in woman-only spaces.

While this seems convoluted and is a misrepresentation of the process of obtaining a gender recognition certificate, the idea took off with progressive papers such as the Guardian publishing anti-trans pieces. Because of this backlash, the GRA was never updated. The relationship between these different institutions – media, legal system, and medicine, worked together to enact powerful restrictions over the bodies, and bureaucratic self-representations, of trans people.

Hated Bodies

British-Australian feminist scholar Sara Ahmed discusses how hate works through bodies in The Organisation of Hate.[10] She argues for emotions as a sort of economy, meaning they carry transferable value. In this way, when an act of hate occurs, such as a transphobic hate crime, the value of the emotion is passed from the aggressor to the victim. The hate is transferred, and so the victim becomes the hated, and the hatred is amplified the more people project it.

This is certainly something that happens to trans women in feminist communities, and even in LGBT+ feminist spaces. At the Dyke March London in 2014, a trans woman speaker was protested, with TERFs proclaiming her a man taking over an event for women and forcing Lesbians to accept the penis, essentially stripping them of their female lesbian identity. Through this act of hate, by refusing to see her as a woman they disallow her to sexually identify as a Lesbian. This takes away huge aspects of this woman’s personhood, due to the perceived male aspects of her body.

Statistics show that 48% of trans people in the UK have attempted suicide and 84% have thought about it. This follows 65% experiencing discrimination or harassment for being trans, and 41% being attacked or threatened in the last five years.[11] These figures are a staggering reflection not only of the hate trans people receive, but how they hate themselves… with Ahmed’s idea of the economy of hate providing a framework for seeing this as transferred, rather than inherent. Not a specific quality of trans bodies, but projected onto or attached to them over time, through historically contingent, and repeated social processes (that include media representations and social media conversations).

Ahmed specifically discusses how the circulation of hate works on the collective bodies of a specific group, by creating a crisis narrative. What TERFs seem to fear most is that a trans woman may be among them without them realising. By framing cis women as victims of trans rights, TERFs make trans women- and their literal bodies- the enemy, and to progress this they have adopted a narrative of violent bathroom attacks in these ‘safe’ single-sex spaces.

A recent study has shown this fear is untrue, and there is no correlation between trans inclusiveness and bathroom safety.[12] Yet this narrative persists, because it projects hate onto trans women. Their bodies have become literal political battle grounds where they fight for the right to simply exist, and to access basic public facilities.

Trans activism in the wake of JK Rowling’s comments

There are, of course, counter-forces to this hatred. Activism by trans people and their allies has continued in response to J K Rowling’s online comments, and after the even more recent announcement that her new crime fiction book, published under the pseudonym Robert Galbraith, features a male killer who dresses up as a woman to kill his victims. It should be noted that Robert Galbraith Heath was the name of one of the earliest psychiatrists to experiment with gay conversion therapy. Although many have seen this as a coincidence, and JK Rowling has denied any connection.

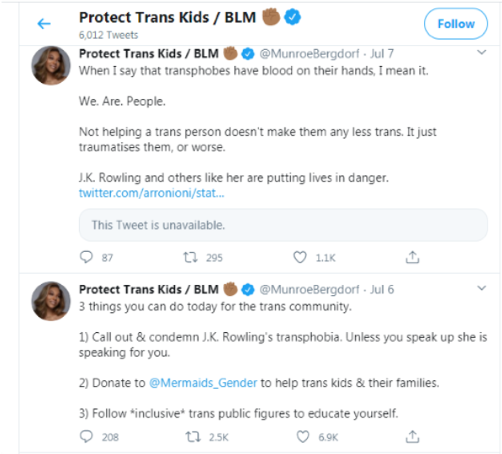

Trans activist and model Munroe Bergdorf, who was in 2014 described as “a cornerstone of London’s trans scene” by the London Evening Standard and was the first trans model for L’Oreal in 2017[13] has been extremely active in her responses on Twitter, offering support for her trans followers, and giving suggestions of what people can do to support the trans community.

Thread from Munroe Bergdorf’s twitter account after JK Rowling’s tweets and essay in July. From https://twitter.com/MunroeBergdorf

“If transphobia is the future of @jk_rowling’s legacy, it’s not going to age well. In writing transphobic FICTION under the pseudonym of a gay conversion therapist, where the overarching moral seems to be ‘never trust a man in a dress’ she is revealing exactly who she is… The REALITY is that trans people are more likely to be murdered, than commit murder. The REALITY is that trans people are already navigating a hostile environment worldwide and this only adds to that hostility. @jk_rowling is dangerous.”[14]

Mermaids, a LGBTQ+ charity that supports trans and gender diverse youth has also called for JK Rowling to think about the impact her statements are having on trans youth. “Trans people are far from being accepted by society and suffer real life discrimination, including physical violence, employment discrimination and everyday harassment on the street. Trans young people should not be used to amplify separate issues such as male violence, bodily autonomy or patriarchy.”[15]

Trans actress and artist Ela Xora who had a filmed role for the Wizarding World of Harry Potter theme park has ripped up her contract and demanded that her scenes are removed from the park in retaliation to JK Rowling’s stance,[16] and many of the crew of the films including Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, Bonnie Wright, Evanna Lynch, Eddie Redmayne, as well as Noma Dumezweni, who played Hermione in the stage play Harry Potter and the Cursed Child have released statements in support of trans people on their social media platforms.[17]

Being (and buying) better

In 2015, the Smithsonian published an article called “Reading Harry Potter may make you a better person,” which stated that people who read the books grew up to be more tolerant and accepting as adults, based on an Italian study.[20] It seems to me now, that perhaps that is still true, as fans have been vocal in calling JK Rowling out for her transphobia.

Many are now feeling disillusioned with the franchise, which, for many of us, was a large part of our childhood and formative years, and helped mould us into the people we are today. It is extremely difficult to separate the author from her works (if that should even be done at all) and has for many tainted something that had a large impact on our lives. I know that myself and many friends will no longer be buying merchandise, or supporting any of JK Rowlings new books or projects, Harry Potter related or not, and some friends are getting rid of all their Potter memorabilia. Fan sites have announced they will no longer discuss JK Rowling or her career.[18]

Fans online are calling for people to email the publishers of her Galbraith novel to let them know that they will not be supporting a company publishing transphobic material, and noting the dissonance between the company publishing such works and also having a Pride feature on their front page showing all the queer and trans novels they publish.[19]

Trans women are women, despite what TERFs will tell you. People like JK Rowling will continue to spout their sex-based hate. But as activists and fans alike are showing, if hate is economic, we can refuse to buy it.

References

[1] Jamieson, Amber. 2020. “JK Rowling Followed up her Anti-trans tweets with a full Anti-trans Essay.” Accessed 25 July 2020 at: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/amberjamieson/jk-rowling-antitrans-statement

[2] Rowling, Jk. 2020. “JK Rowling Writes about her Reasons for Speaking out on Sex and Gender Issues.” Accessed 25 July 2020 at: https://www.jkrowling.com/opinions/j-k-rowling-writes-about-her-reasons-for-speaking-out-on-sex-and-gender-issues/

[3]Wareham, Jamie. 2019. “ Murdered, Hanged and Lynched: 331 Trans People Killed this Year.” Accessed 25 July 2020 at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamiewareham/2019/11/18/murdered-hanged-and-lynched-331-trans-people-killed-this-year/#675d66c22d48

[4] Hines, Sally. 2019. “The Feminist Frontier: on trans and Feminism” Journal of Gender Studies. 28:2. p.145-157.

[5] Raymond, Janice. 1979. The Transexual Empire: The Making of the She-male. United States: Beacon Press.

[6] Lewis, Sophie. 2019. “How British feminism Became Anti-Trans.” Accessed 27 July 2020 at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/opinion/terf-trans-women-britain.html

[7] Ewens, Hannah. 2020. “Inside the Great British TERF War” Accessed 27 July 2020 at: https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/889qe5/trans-rights-uk-debate-terfs

[8] Feder, Sam. dir. 2020. Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen. Los Angeles: Bow and Arrow Entertainment. Netflix.

[9] Miles, Laura. 2018. “Updating the Gender Recognition Act: trans oppression, moral panics and implications for social work. Critical and Radical Social Work. 6:1. p. 93-106.

[10] Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “The Organisation of Hate.” In The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

[11] Stonewall. date unknown. “Trans Key Stats”. Accessed 29 July 2020 at: https://www.stonewall.org.uk/sites/default/files/trans_stats.pdf

[12] Moreau, Julie. 2018. “No Link between trans-inclusive policies and bathroom safety, study finds.” Accessed 30 July 2020 at: https://www.nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/no-link-between-trans-inclusive-policies-bathroom-safety-study-finds-n911106

[13] Wikipedia. Last updated 7 September 2020. “Munroe Bergdorf.” Accessed 20 September 2020 at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munroe_Bergdorf

[14] Bergdorf, Munroe. 2020. “Twitter thread.” Accessed 20 September 2020 at: https://twitter.com/MunroeBergdorf/status/1306275552957997058

[15] Mermaids. 2020. “A call to JK Rowling.” Accessed 17 September 2020 at: https://mermaidsuk.org.uk/news/a-call-to-j-k-rowling/

[16] Maurice, Emma. 2020. “Trans Harry Potter actor rips up her contract and demands JK Rowling pays attention to thousands of years of transgender history.” Accessed 30 July at: https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2020/06/13/jk-rowling-trans-transgender-harry-potter-actor-ela-xora/

[17] Lenker, Maureen. 2020. “Every Harry Potter actor who’s spoken out against JK Rowling’s Controversial Trans Comments.” Accessed 20 September at: https://ew.com/movies/every-harry-potter-actor-whos-spoken-out-against-j-k-rowlings-controversial-transgender-comments/

[18] Murphy, J. Kim. 2020. “’Harry Potter’ Fan Sites will Minimise Future J.K. Rowling Coverage after Condeming Anti- Trans Views. Accessed 20 September 2020 at: https://variety.com/2020/film/news/harry-potter-jk-rowling-mugglenet-leaky-cauldron-anti-trans-1234697127/

[19] untitled Tumblr post. 2020. Accessed 20 September 2020 at: https://thesweetpianowritingdownmylife.tumblr.com/post/629503862222553089

[20] Lewis, Danny. 2015. “Reading Harry Potter Might Make you a Better Person.” Accessed 20 September 2020 at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/reading-harry-potter-might-make-you-better-person-180955196/

Incels ‘cash out’: gendered violence and the economies of hate

A post written by Jazzlin Carr, based on an ANTH424 assignment.

“He doesn’t seem like that bad of a guy. He just seems hurt, like he just wants a friend or support. I always thought incels were really bad people, but he seems like a good version of them.”

I looked over at my very liberal, ultra-feminist, Jacinda Ardern-loving partner in disbelief. We had just finished watching a YouTube video from the channel Jubilee entitled “I’m An Incel. Ask Me Anything.”.[1] The short clip features a self-proclaimed incel responding to questions from the public. While his identity is hidden from those asking the questions, he is shown to the camera.

A screenshot of the Youtube video “I’m an Incel, Ask Me Anything” posted by Jubilee. In this particular frame, a woman appears to be pointedly interrogating an incel named Derrick, whose demeanour and open palms facing up depict a certain passivity and openness. Source: https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=incel

An incel, otherwise known as an “involuntary celibate”, is a self-imposed label used by mostly young males who define themselves by their inability to secure romantic or sexual partners despite having the desire for them, often attributing this to their anxious or shy behaviours, women’s high standards, or their unattractiveness or below-average characteristics. [2] They are most often found in online forums, where discussions are often characterized by self-loathing, resentment of more attractive males (known as “Chads”), and misogyny.

This definition, however, is fluid depending on who you ask. As one incel claims in his blog, anyone can be an incel “as long as they show signs of […] struggling with attaining romantic relationships”. [3] Others, myself included, would characterize the self-radicalizing nature of incel communities as a key part of the definition. Take a scroll through one of the few incel chatrooms that have not been blacklisted from internet servers and you’ll be hard-pressed to find a single discussion that does not dehumanize women, promote racist ideologies, encourage violence, or celebrate incels who have murdered women out of spite. [4]

You may not have assumed such a thing if your only portrayal of incels is from the Jubilee video I noted above. The incel featured, named Derrick, coolly responds to a variety of questions. He reacts to leading questions with calmness and ensures the interviewers that he is there “to give more of a positive light on [the incel] community”. He discusses his mindset, believing that “promiscuity leads to increased standards in more primitive aspects such as looks and that typically makes it harder for some people to find relationships” and generalizes this to cities such as “[Los Angeles] or London, or in Auckland, New Zealand”. He notes that it was “constant years of rejection” that led him to more “radical beliefs” which he equates to “old beliefs”. It is also noteworthy that he was very quick to say that he condemns the actions of mass murders identifying as incels. Instead, he thinks “the reason why they committed those actions was […] desperation, or […] mental problems.”. When watching the video again, I can understand where my partner’s empathy to Derrick comes from. His demure presence, calm responses, and position as a “traditionalist” who has been hurt time after time again presents a convincing case towards justifying the incel perspective as a matter of difference of opinions, or a wounded community seeking internal support.

But what is the actual impact of this point of view, on the lives and bodies of women? I turn to the writing of British-Australian scholar, Sara Ahmed, to explore this:

“It is the failure of hate to be located in a given object or figure, which allows it to generate the effects that it does” (2004, p49).

In her book The Cultural Politics of Emotion, author Sara Ahmed discusses the organization of hate, and considers its circulation as both a defence mechanism for those who see another body as a threat to something they love, as well as its impacts on the figures who have been aligned by the narrative of hate as the “common enemy”. [5]

Her analysis seemed fitting for this topic and applying it to the performance of incels has me wonder if it may clarify why Derrick’s narrative could almost seem, dare I say, justified.

In a chapter on hate, Ahmed’s overarching theme is that hate operates as a sort of economy. Essentially, hate is fluid and moves between bodies and signs, and is not fixed on one subject. If an incel posts a rant on a chatroom about his displeasure with a woman who rejected him that day, the specific woman involved is simply a “nodal point in the economy”. The hate has another origin and destination, one which is more broadly connected to the perceived threat towards something the incel desires. In this instance, it may be their desire for a relationship and feeling loved. From this perspective, the hate’s origin was not in the encounter with the individual woman, but rather in years of rejection. The destination of that hate is not towards her, but rather, to a common body of women which the incel deems as a threat to ‘traditional’ relationships that they wish to participate in, but feel they are blocked from. In this example, we see how an incels hate is economic.

It is this inability of hate to be fixated that allows it to grow and fester in these groups. The vagueness of the enemy allows for particular narratives to be applied to any individual who may appear to be a part of that group. In the case of the incels, any woman could therefore fit the narrative as being a threat to traditional relationships.

But how does this economy of hate affect the bodies of the group considered a “threat”?

“There can, in fact, be no hatred until there has been long-continued frustration and disappointment” (Glenn Allport, in The Nature of Prejudice, quoted by Ahmed 2004, p50).

Derricks relatively innocuous comments contribute to the investment of hate towards women by furthering a narrative that their desire for more liberal roles and modern lifestyles is raising their expectations of men to the extreme, so that more traditional or less attractive men can no longer find relationships or love. For one, it is rhetoric that seals female bodies as objects of hate. This kickstarts a chain of effects that promote and support violence. It contributes to real physiological symptoms for those who must live in these bodies in a number of broader ways too. This is evident in the below photo, selected by Stuff for its news article on the event in 2015, which depicts the consequences of incel behavior on women who are not direct victims of its violence, who instead may suffer from fear, post-traumatic stress disorder, nightmares and anxiety

Two women comfort each other following the Umpqua Community College in Roseburg, Oregon. This attack killed 10 and injured eight others. The attacker was an incel, who expressed sexual frustration and blamed women’s standards for his virginity at age 26. Credit: Steve Dipaola/Reuters. Source: https://www.stuff.co.nz/world/americas/72625797/10-dead-in-shooting-at-umpqua-community-college-in-roseburg-oregon

If hate is an economy, it also performs as a form of capital. The effect of an incel’s hate does not reside solely in the individual object of their displeasure, but rather accumulates over time. I would take Ahmed’s imagery of hate as an economy a step further, and argue that is when these investments pile up and a member of the threatened community tries to “cash out” on this accumulated capital of hate that violence is used as a defence against the hated bodies. The collection of testimonies of rejection, frustration, and disappointment found on these incel chat rooms becomes so overwhelming that an incel feels justified in reacting with violence, in the same way as a person who has accumulated savings may feel enticed to splurge with the surplus.

The investment of hate on these chatrooms is made evident in the justification of violence on women when researching any of the major incel-led terror attacks of the past couple decades. After a one self-described incel posted a 137-page manifesto to a chatroom in 2014, he would thereafter kill six people and wound fourteen more in Isla Vista, California. The reaction from the online incel community was one of praise; his face quickly photoshopped onto Christian icons, and his name being associated as the “primary incel ‘saint’”, a reflection of how they believed he was the saviour of incel values. [6] In 2015, an incel in Oregon shot and killed nine classmates and a professor, and injured eight others, in what he described in his manifesto as the reaction of his frustrations to being a virgin at 26. The reaction from the incel community was one of support and empathy, with one user commenting a poem, reading “society failed him/it’s not his fault/don’t blame him/he was the hero we deserved.”. [7]

A screenshot taken from an incel forum in August 2020. The commentator notes how the van attack in Toronto was “lifefuel” for them. They go on to note preferred methods of killing in “ER” attacks, a popular incel abbreviation for violent attacks. “ER” is a reference to the initials of the “Saint” of the incel community, the Isla Vista killer. Source: http://wehuntedthemammoth.com/2018/04/24/incels-hail-toronto-van-driver-who-killed-10-as-a-new-elliot-rodger-talk-of-future-acid-attacks-and-mass-rapes/

In 2018, an incel in Toronto, Ontario used a rented van to kill ten victims and injure an additional sixteen, as a form of revenge for perceived sexual rejection from women. Most clearly evidencing the use of hate as capital for the incel community, one commentator on a chatroom posted “This shit right here is lifefuel for me”. [1]

A photo (taken 24 April 2018) of the impromptu memorial created by local residents after the Toronto Van Attack, where a man drove along the sidewalk for 2 kilometers, purposefully hitting as many pedestrians as it could. The perpetrator posted on his Facebook account shortly before the attack, with a statement referencing a man considered to be the “Saint” of incels. Credit: Quentin9906. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The original quote from my partner, that opened this blog, shows how important it is to grasp the economy of hate. Even though my partner did not agree with Derrick’s views, the empathy he felt for him could be a slippery slope into justifying the mindset of an incel, thus giving their alignment of female bodies as a threat imagined ground.

The accumulation and investment of this hate is what contributes to not only the everyday pain and victimization of women but leads to the in-group justification of violent expressions of hate, performed in terror attacks such as those mentioned above. In recognizing the performance of hate as an economy, one can work to actively question its impacts and limit the influence one perspective may have on the incel community.

References

[1] I’m An Incel. Ask Me Anything. (2019). YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DdHqzr4DyIs.

[2] Opinion | Men are in trouble. ‘Incels’ are proof. [online] Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/men-are-in-trouble-incels-are-proof/2019/06/07/8d6ad596-8936-11e9-a870-b9c411dc4312_story.html.

[3] SeventhQueen (2020). The Incel Among Us. [online] Incel Blog. Available at: https://incel.blog/the-incel-among-us/

[4] Inceldom Discussion [Online] Incels.co Source: https://incels.co/forums/inceldom-discussion.2/

[5] Ahmed, S. (2015). The cultural politics of emotion. New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

[6] Beauchamp, Z. (2019). Incels: a definition and investigation into a dark internet corner. [online] Vox. Available at: https://www.vox.com/the-highlight/2019/4/16/18287446/incel-definition-reddit.

[7] bust.com. (n.d.). ‘Beta Males’ Want To Kill Women Because They Can’t Get Laid. [online] Available at: https://bust.com/feminism/15551-mo-beta-blues.html

[8] We Hunted The Mammoth. (2018). Incels hail Toronto van driver who killed 10 as a new Elliot Rodger, talk of future acid attacks and mass rapes [UPDATED]. [online] Available at: http://wehuntedthemammoth.com/2018/04/24/incels-hail-toronto-van-driver-who-killed-10-as-a-new-elliot-rodger-talk-of-future-acid-attacks-and-mass-rapes/

The suffering of war, the eye of the beholder

A post written by Samuel McComb, for an ANTH424 assignment on ‘visual images and the communication of suffering and evil’.

“What has been seen cannot be unseen, what is has been learned cannot be unknown.”

– C.A Woolf

I love art. Creation in different forms has provided me with an outlet where nothing else can, and exposed me to works that have not left me to this day. Some I have carried lightly, while others remain as haunting as the first time I laid eyes on them.

One particular image has remained with me in a way others have not. It sits clearly in my mind’s eye. Without demanding focus or derailing the bustle of other thoughts, it simply reminds me of its presence with a whisper – “I’m still here”. For years I have held space for it, maintaining an uneasy truce. Decontextualized, it could do no harm nor be put to rest. But upon its most recent resurgence I felt compelled to understand more. I could not have predicted how thoroughly this discovery would challenge my perception.

Witnessing

My familiarity with this image harks back to my high school years. I was around 16, or perhaps 17, and in the midst of what one might describe as a period of healthy teenage angst, channelled and encouraged by an art department with an affinity for the grunge aesthetic. A plastic skeleton lived in the corner of the art room. The gift of a perfectly mummified cat (found when a neighbour’s house was relocated) received promises of “Excellence” grades for the year’s NCEA assessments. One lunchtime, two friends and I made the plastic skeleton a cardboard house, in the middle of the classroom. It was in this environment that our subject matter would be deconstructed, remade and distorted as we explored our theme; War.

Paul Frosh (2016), a media and communications researcher with the Department of Communication and Journalism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, made a strong argument that our ability to respond morally when witnessing suffering is shaped by how we view it – the medium used in its portrayal changes how we engage our senses. His conclusions are drawn from an analysis of user experience with Graphical User Interfaces (GUI’s) of smartphones and computers when viewing Holocaust survivor testimonies . These provided clear examples of how the experiences and actions we take when witnessing suffering shape our response.

Frosh then considered the moral obligations of the viewer when witnessing and responding to suffering. He divided these responses into three types: attention, engagement, and action. This was a useful framework within which view my own interactions with, and responses to, suffering, and specifically to explore how this raw image (fig.1) became the work I presented in my high school art folio (fig.3).

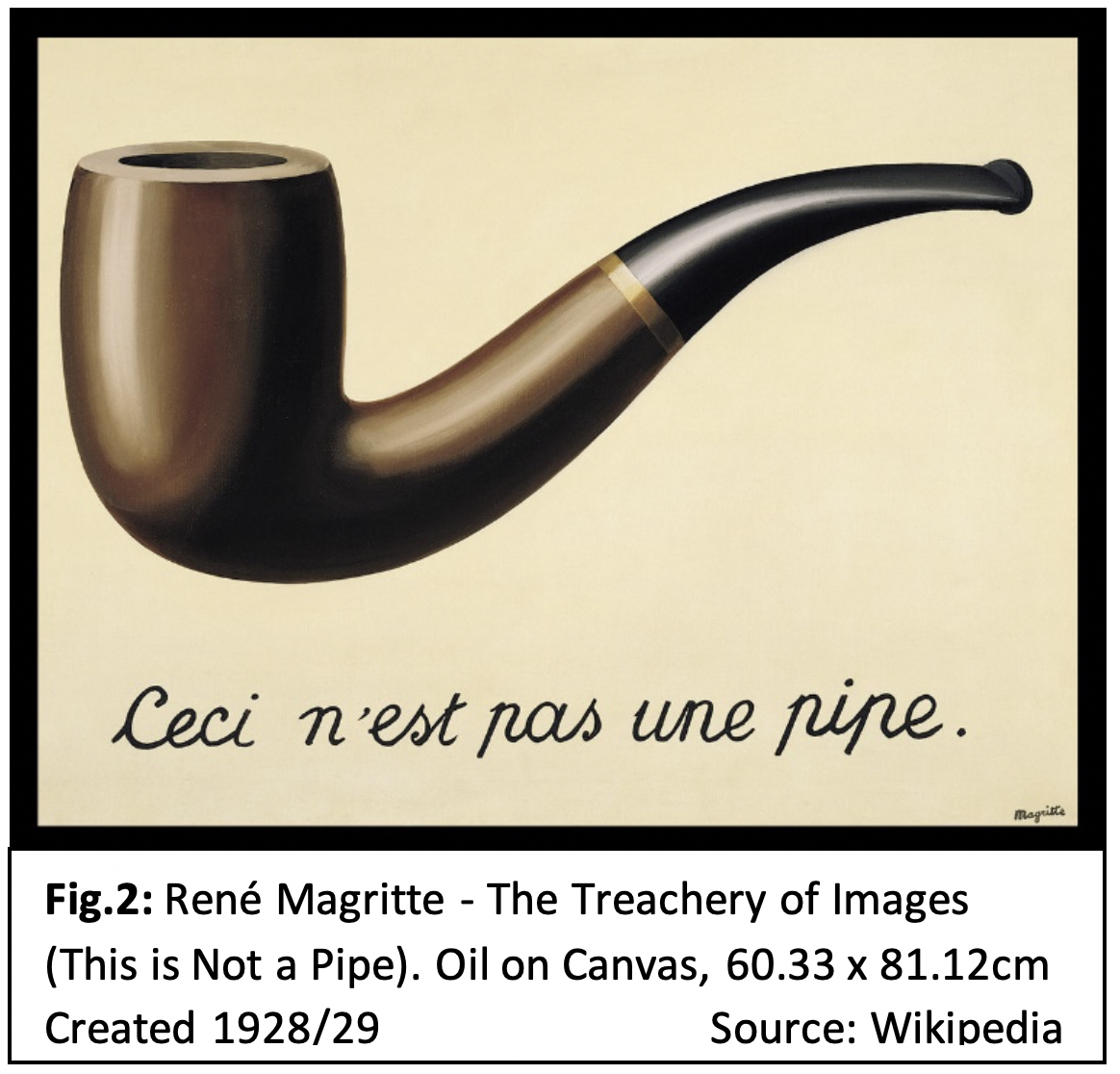

Attention

René Magritte famously captioned his pipe painting ’This is Not a Pipe’ (Fig.2); in other words, an image is not the object it represents. This is an influential idea in semiotics and fundamental to art.

René Magritte famously captioned his pipe painting ’This is Not a Pipe’ (Fig.2); in other words, an image is not the object it represents. This is an influential idea in semiotics and fundamental to art.

As I began my project, I was searching for images and shapes that represented an idea or a feeling. I first saw the soldier while shuffling through a stack of photocopies collected from old books and internet searches. These photos of medals, memorials, soldiers and statues had been carefully selected by the teacher to help us explore our theme. I recall that several images had been ripped by other students fighting for the ‘cool’ pictures – the ones with the biggest guns – by the time I began my search.

On one level these were just raw materials, no different to any other aesthetic resource provided by the teacher. Yet just as Frosh (2016) argued that how we access depictions of suffering plays a major role in our responses, the way I was searching for images shaped my response. I was holding history between my fingers, taking just enough time to gain some perspective of the content as I shuffled through the photocopies, before passing the stack of unsuitable pictures to the boy beside me. I could almost forget the reality behind the paper as I traced shapes overtop of figures, the smooth monotony of the paper interrupted by creases and rips as I thought of textures and colours to represent what I felt each copy contained. After the preliminary search, every raw image was subject to a deeper focus – I wanted to know what aspect of each photo captured my attention.

Action

Once we have seen suffering we are faced with a moral decision in how we respond. I could choose to ignore what I saw and felt in the image of this young soldier. I could choose another image, another topic to explore – my resulting artwork would have been displayed in the same way, to the same audience, regardless of the content. I could have found more images of big guns, but I didn’t. I needed to share what I had seen and felt.

Frosh (2016) describes the primary response to suffering in the digital age as communicative action – sharing a video or photograph widely, to raise awareness and prevent further actions, or simply to acknowledge that the suffering occurred. Sitting in my classroom, I needed to share what I had felt when I saw my soldier – the destruction of innocence that does not choose a side, the shared suffering inflicted on humanity through war. In this case though, sharing was not the quick click of a digital button, but a belaboured process of interpretation and creation with paint.

Sometimes we can choose to filter or curate our media feed, hide from the suffering before it overwhelms us. As in social media, so too in art we can choose to cover what we don’t want to see and focus on brighter times. Indeed Frosh (2016) makes clear there is the potential, when communicating enormously tragic events, for individual stories to be lost and the narrative of suffering to become overwhelming; the viewer becoming helpless and unable to respond morally to all they are exposed to. Reflecting on my folio (fig.3) certainly could elicit this response, I have to now reflect, as the young soldier becomes one small feature within the whole composition, one piece of a larger picture.

For a moment the viewer too feels the overwhelming weight of suffering that exists behind the barrier of our screens, and we become like my soldier, or perhaps the photographer – left with nothing but the ability to witness and remember.

Revelation

I never tried to find out more about the photographs I used at the time, nor in the ten years since I made this board. I knew the wars they came from, perhaps who they fought for, but not the stories of the men. In hindsight I was hiding from the full truth, keeping the distance of ignorance to keep from being overwhelmed. The folio received an Excellence, and placed second in my school that year, yet I have been almost ashamed to share it knowing so little about the history of my source materials. The most recent time my soldier whispered, I listened, intending at last to let him rest.

To my surprise it turns out the soldier who inspired my art, who has stayed with me for so long, was a work of fiction – filmmaker Berhnhard Wicki’s own moral response to suffering. My soldier’s photo was in fact a still from his film “Die Brücke”. Released in 1959, this West German film follows a group of seven 16 year old school students enlisting late in 1945. The film shows their experiences as they are sent to defend a bridge in their home town with almost no training, and all but one of the boys die as they experience the horrible reality of war. The film ends noting that it was based on a true story (IMDB, 2020).

Several things suddenly made sense when I found this out. Firstly, the affinity I had felt was real because the soldier was my age. Secondly, everything had been designed to elicit an emotional response from the viewer – camera angle, posture, positioning. I wondered if it was a sense of difference that made my soldier’s photo stand out among the stack – subconscious awareness that it was somehow wrong, or staged. But I soon realised that did not matter.

The intent of Die Brücke was to share an emotional response to the horror of war. More than fifty years on it continues to do so with just one frame. In doing so it continues to offer me a choice of moral action – turn away from the suffering, or witness it, and share a moral response of my own. The eye of the artist may say “This is Not a Soldier”, but through the eye of the beholder we can still say “This is Suffering”.

Sources:

Frosh, P. (2016). The mouse, the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response. New Media & Society, 20(1), 351–368.

The Bridge. (1959, October 22). Retrieved April 10, 2020, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0052654/

Fig.1 Source: Teeuwisse, J. H. (2017, March 3). NOT a photo of German child soldiers at the end of WW2. Retrieved April 2020, from https://www.flickr.com/photos/hab3045/33231024585/in/photostream/

Fig.2 Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Treachery_of_Images Retrieved April 2020

Fig.3 & Fig.4: My own work, photographed April 2020

Women Walking Alone: An ethnographic soundscape

A soundscape produced by Laura Gunther, for ANTH210 (Translating Culture)

About the soundscape:

The soundscape I produced for ANTH210 responded to my research question: ‘What are some of the challenging experiences of being (cisgender) female in Dunedin?’

The soundscape I produced for ANTH210 responded to my research question: ‘What are some of the challenging experiences of being (cisgender) female in Dunedin?’

This is a topic that felt most relevant to me and what was/is applicable to Dunedin culture. In order to encompass this in an audio format, I explored both my personal experiences as a woman, along with those experienced by others through a collection of audio recordings, woven together to produce the sound of a woman walking alone at night.

About the ANTH210 process:

The process of recording the soundscape audio came with its challenges; sound interruption was one of them. Many of my audio clips had to be re-recorded in order to achieve what I wanted out of my ethnographic research. Furthermore, finding relevant audio recordings came as a struggle. It came as quite a challenge to decide upon sounds produced within Dunedin that would provide me with the environment I had pictured within my mind. While this was eventually resolved, I also feared that my lack of technological experience would interfere with the quality of my soundscape, and I continued to believe this up until its submission. But thankfully, I recall that technological experience is not what defines the quality of a soundscape – rather it is its content and how it all comes together that matters.

My chosen format for the soundscape was intended to immerse the listener into the mind of a fearful woman – as many feel – when travelling alone at night. While this is not felt by all women, I wanted to produce a soundscape that was a harsh reality. Through these chosen sounds, a woman’s experiences, along with fears, is captured – producing an insight as to what a woman may experience – even in a student environment such as Dunedin.

Emmett Till: the photograph that made a martyr, started a movement

Written by Amy Hema, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424.

Emmett Till as pictured at his funeral, in an open casket; deformations the results of the violent nature of his race-based murder.

When thinking about images of evil, this photo immediately comes to mind. I was introduced to it eight years ago, and to me it has always been the epitome of evil.

The photo is of a young boy named Emmett Till, who became a martyr for the US Civil Rights movement after his tragic murder.

But how did one tragedy influence a whole country? With a photograph.

The Murder of Emmett Till

Emmett was a 14-year-old African American boy, who in the summer of 1955 travelled from his hometown [1] Chicago to Mississippi. Before boarding the train, he kissed his mother goodbye, unbeknownst to them both, for the last time.

On August 24th Emmett entered Bryant’s market in the small-town of Money.

The interaction that took place in that store has been debated for decades, but what was reported at the time was that Emmett had been inappropriate with and whistled at the white grocery clerk, Carolyn Bryant [1]

Four days after the alleged incident Carolyn’s husband and his half-brother entered the home where Emmett was staying. They kidnapped, tortured and killed Emmett before tying a cotton gin fan to his neck and throwing his body into the Tallahatchie river, where it would be discovered days later. Emmett’s body had been so badly beaten, the only way to identify him was by his father’s signet ring [1]

Photograph shows the jury at the trial of two white men, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, charged with murdering Emmett Till. 9/20/1955. Courtesy: Library of Congress

Roy Bryant and J W Milam were arrested and charged with murder.

They were tried in front of an all-white jury, in a scene Harper Lee herself could have written. After only an hour of deliberation, both Bryant and Milam were found ‘not guilty’[2].

A photo that incensed a nation

I argue that the reason why Emmett became a ‘martyr’, in the sense of his death taking on wider moral and political meaning, is because this photo of his body exists.

Emmett Till was not the first boy to be lynched. At the time, lynching was part of lived reality of African-American communities in the USA [3]. The difference for Emmett is the proliferation of this photograph. This photo exists because Emmett’s mother, Mamie Elisabeth Till-Mobley, made an incredibly difficult decision; to have an open casket funeral. Mamie had to fight for her sons remains to be returned to her, and when she received his remains, she was told the casket had to remain closed [1]

Mamie Till looks stoically over her son. David Jackson (1955). Source: Time: 100 photos http://100photos.time.com/photos/emmett-till-david-jackson NB. In other photos Mamie leans over the casket with an expression of absolute pain and grief.

However, after seeing the horrors that were inflicted upon him, Mamie knew the world had to see what she had seen[4]. The existence of this photo is the enactment of her moral obligation, to a child who could not share his story which needed to be told, and to the world that needed to hear it.

Photos of the body were circulated by Jet Magazine, capturing the brutality of the violence that Emmett had suffered. At the time, these images were circulated within African American audiences only. Being too brutal to publish in mainstream magazines, it would be years before the image became a global phenomenon.

I link this to what anthropologists Kleinman and Kleinman have discussed as the role of suppression in visual representations of suffering[5]. Withholding evidence of suffering denied the public the chance to stand as moral witnesses. The circulation of images like this often by nature only convey one ‘slice’ of a complex reality. However by choosing to not circulate his image, mainstream media outlets were denying and erasing the suffering of Emmett, his family, and the African-American community.

Emmett and the Civil Rights Movement

Kleinman and Kleinman have also argued that images have been used to confront viewers with a moral issue, and call for social action[5]. The photo of Emmett Till is a prime example of moral sentiment being used to rally people toward social justice. Sociologist Joyce Ladner coined the phrase the “Emmett Till Generation” of black activists, to describe the individuals living in the United States who after the death of Emmett Till became heavily involved with civil rights. That term offers a perfect summation of how the image impacted the lives of African Americans[6].

Many consider Emmett’s death and the circulation of the photos to be a catalyst for the civil rights movement, influential activists stated that the death of Emmett had a significant impact on their lives and consequentially their involvement with the civil rights movement. In her memoir, Anne Moody details how the death of Emmett Till made her aware of her own position within society, how after his murder she became afraid of being killed because she was black. Moody went on to describe the rage she felt, at the people who had killed Emmett and the African Americans who, out of fear, stood by and allowed these things to keep happening[7]. Moody’s personal history with the photo demonstrates how moral witnessing, in visual form, not only rallied a generation but created new understandings of how people fit into the world.

Only a few months after the circulation of Emmett’s photo, Rosa parks famously refused to give her bus seat to a white woman, leading to the Montgomery Bus Boycott. When asked why she made that decision she said, ‘I thought of Emmett Till and when the bus driver ordered me to move to the back, I just couldn’t.[4]’

Although Emmett may have not been directly responsible for the civil rights movement, his image was a confrontation of the truth; people could no longer deny that these things were happening and that they could happen to any Black American.

Why does Emmett Till still matter?

Racism still exists within the United States, albeit not in the same way it did 60 years ago. There are no signs separating water fountains or bathrooms. But racism persists in the form of stereotypes, inequality in housing, education and employment opportunities.

Racism in the USA today is the over-representation of unarmed African American teens being killed. Each time there is a killing of a black male in the US, Emmett’s name re-enters the spotlight[8], through his image he has become forever linked with racial violence. Emmett Till was the face of the Black Lives Matter Movement before it existed.

One of the most notorious killings in recent history was that of Trayvon Martin, following the murder of Martin, Emmett Till was once again thrusted into the spotlight. Trayvon and Emmett’s deaths shared a striking resemblance, as the Washington Monthly put it “Separated by a thousand miles, two state borders, and nearly six decades, two young African American boys met tragic fates that seem remarkably similar today: both walked into a small market to buy some candy; both ended up dead.[8]”

The fact that Emmett is still brought up to this day, as a representation of racism and hatred is testament to the power not only of his photo but of images in general, they are lasting, they freeze a moment in time and hold it there. Emmett will never stop being a martyr, because he has been frozen in time as one.

Despite the immense influence of this image, there is still a few glaring questions; sixty years after the circulation of the photo of Emmett, how is it that we are still in the same place? How is it that we are still being bombarded with images of African- American suffering? Have we become, as Frosh put it, desensitised [9]?

We are in a unique period where we can constantly access news and images, in every facet of our lives we are exposed to the suffering of others, but from a position that is so far removed, after a while it becomes harder to empathise. Have we become numb to these killings?

And finally, how many more Emmett Tills will we have to look upon before people change?

References:

[1] See the Documentary: ‘The Murder of Emmett Till’ (2003, PBS).

[2] PBS (n.d.) ‘The Murder of Emmett Till: The Trial of J.W. Milan and Roy Bryant’. PBS: The American Experience. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/emmett-trial-jw-milam-and-roy-bryant/

[3] In the 75 years leading up to Emmett’s death, it is estimated the over 500 African American’s were lynched within Mississippi, most of them were men accused of associating with white women. https://youtu.be/7uTtNnCw69w?t=426

[4] The Washington Post. ‘Emmett Till’s mother opened his casket and sparked the civil rights movement’. The Washington Post. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/07/12/emmett-tills-mother-opened-his-casket-and-sparked-the-civil-rights-movement/

[5] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. 1996. ‘The Appeal of Experience; the dismay of images: Cultural Appropriations of sufferings in our times.’ Daedalus, 125(1).

[6] Kolin, P.C. The Legacy of Emmett Till

[7] Moody, A. (1968) Coming of Age in Mississippi. Penguin Randomhouse reprint.

[8] Gorn, E.J. (2018). ‘Why Emmett Till still matters’ Chicago Tribune. July 20th. Available: https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-emmett-till-mississippi-murder-reinvestigation-whistle-white-woman-carolyn-bryant-20180722-story.html

[9] Frosh, P. (2018). ‘The Mouse, the screen and the holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response’, New Media & Society, 20(1), pp351-368.

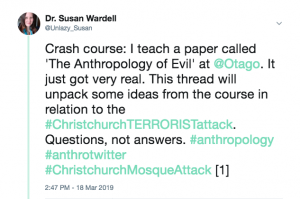

A crash course on the anthropology of evil

Dr Susan Wardell teaches a course called ‘The Anthropology of Evil’ (ANTH424). Last week she responded to the Christchurch mosque shootings with a twitter thread, drawing on course content to ask pointed questions about social patterns of sense-making in New Zealand, and in the media, in the wake of the attack. The full (19-point) thread is available in the link below, and also pasted as text below

https://twitter.com/Unlazy_Susan/status/1107760378694385664

Crash course: I teach a paper called ‘The Anthropology of Evil’ at @Otago. It just got very real. This thread will unpack some ideas from the course in relation to the #ChristchurchTERRORISTattack. Questions, not answers. #anthropology #anthrotwitter #ChristchurchMosqueAttack [1]

When the world is shattered, human meaning-making kicks in fast. We try to ‘locate’ evil within existing worldviews, including theological, secular, and academic. We collectively ask what/who/where, & WHY?! This gives us the social resources to assign blame, prescribe action. [2]

What is ‘evil’? An inherent quality of a person? Their intention/motivation? The action itself? The consequences of the action? Watch how the media and legal system frames this for #ChristchurchTerrorAttack. And what about a white supremacist who has never committed violence? [3]

What role can social scientists play in responding to the #christchurchtmosque attack? Should we be thoroughly analysing moral topics, whilst bracketing our own views (Fassin 2009), or formally taking sides, being politically engaged (Scheper-Hughes 1995) #anthrotwitter [4]

Does social science have a language appropriate to representing suffering? Is this thread itself unethical, in its stilted, theoretical removal from very real pain, grief, loss of the #ChristchurchMosqueShootings? How should we analyse atrocity without being reductive, cold? [5]

I’ve seen many posts arguing against learning the terrorists name and background because they don’t want to ‘humanize him’. It’s easy to create a ‘monstrous’ other. Monster = not human. But he is a human. That’s scarier to acknowledge. HE is us, as well as ‘they’ are [6]

The terrorist is described as ‘evil’.”‘Evil’ is part of the vocabulary of hatred, dismissal, or incomprehension” (Morton 2004). SHOULD we seek to understand the lives, worlds, & thinking of white supremacists? Are condemnation & understanding incompatible? [7] #anthropology

How are we fitting the story of the #christchurchmosqueattack into existing, familiar narratives? What is the risk? Yesterday a student & I bet that we would soon see references to mental illness – a common narrative for white male violent offenders. Came true within hours. [8]

What elements of news about the #christchurchmosqueattack have affected you most? I’m going to guess it’s the images. Images are sometimes seen as a more authentic language for pain than words, but also function to ‘frame’ complex realities. Reflect on the ones you’ve shared [9]

Kleinman (1996) warns that mass media circulation of images means suffering can be “remade, thinned out, distorted”. Susan Sontag saw photography as ‘predatory’. Let’s think about: who took the images and why? Who is sharing them, and why? Who is in them, and who isn’t? [10]

Frosh (2016) discusses digital morality: the cursor as a proxy moral compass. What do we click on, or watch, & why? A sense of obligation to ‘witness’ tragedy? Empathetic hedonism? (Recuber 2016, also see: https://blogs.otago.ac.nz/inplural/wp-admin/post.php?post=122&action=edit … ) What would it mean to NOT watch/view/click? [11]

Lots of discussion about what NOT to view (the manifesto, the livestream). Calls to give attention to victims, not perpetrator. We are exercising agency, within the ‘attention economy’ of social and mass #media. Capital-driven systems, but with room for resistance. [12]

What makes something or someone LOOK evil? How are particular features of particular bodies, coded as evil? Places and objects can also take on strong (through fluid) meanings, and emotions. What have mosques symbolised in NZ in the past? Now? What about the hijab? Guns? [13]

A typical terrorist tale involves a villain who has infiltrated a community, but is an outsider (Loseke 2016). Does the fact that the #christchurchmosqueattack terrorist was an Australian, change how NZ will address its own racism? Do we still get to be the ‘goodies’? [14]

How does hate come to circulate around specific people, bodies, or identity markers? Sara Ahmed (2004) writes is not not just part of ‘extremism’ and crime, but is a “product of the ordinary” Hate crimes do not just involve visceral power, but broader structures of power [15]

‘Banal’ evil refers to everyday, complicit, thoughtless evil (not sadistic malice). Is racism in NZ like this? Is racism part of ‘structural evil’: the longstanding formal (legal/bureaucratic/political) systems that discriminate and harm through their normal functionality. [16]

It’s through the cultivation of collective emotions that people come to FEEL, to BELIEVE in the imaginary social unit called the ‘nation’. In NZ’s past, who has been ‘othered’ to build a stronger sense of ‘us’? What does it mean to now say ‘they are us’, & is it enough? [17]

There has been talk about lack of Muslim voices even in the mainstream media coverage of the #ChristchurchTerrorAttack. Testimony has a power not despite, but BECAUSE of subjective experience. When Muslims say they are shocked, broken, but not SURPRISED, are we listening? [18]

Silence can help diagnose power. We must pay attention to silences, gaps in narratives, forgetting, vagueness, or selective remembering, about our own history, including the many instances where white supremacists acted publicly in NZ before this, as pointed out in a blog post by Catherine Trundle (an anthropologist from Victoria University, Wellington): https://bit.ly/2TIJ4Ti [19]

Easy Words: An Open Letter to Critic

Dear Critic – Te Arohi – Student Magazine,

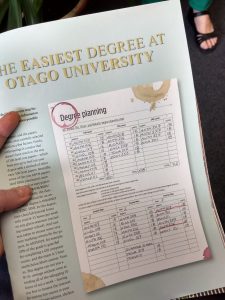

Title image from the Critic article [25th Feb 2019]

To be honest, I think we were more perturbed about the handful of our papers that you decided were too ‘difficult’ to include.

Critic’s dabbles in degree planning… featuring ANTH325 (Death, Grief, and Ritual) and ANTH327 (Anthropology of Money)

But it makes me think a little more about why we study what we do, at Uni. Why would we want a degree that was ‘easy’? Critic’s analysis of a dream degree holds some internal contradictions about achievement, it seems to me…

The article is a ‘how to’ guide for the minimum effort possible to achieve a qualification. This is erroneously calculated of course: all 18 points at the University of Otago are designed to be around 10 – 15 hours of both contact and non-contact time per week. Papers pass through a rigorous review to ensure this – ask the OUSA education officer, who sits on these Divisional Academic Committee Meetings!

Social anthropology papers include large amounts of background reading, ethically approved fieldwork and independent study and analysis, alongside contact hours – skipping over these elements of learning are not the pathway to an A+ but perhaps a C.

But let me return to what it is that we value in our degrees. Is it the piece of paper and a string of Cs? Or is it the experience, the self awareness and critical insights that a capacity for life long learning instills in us? Critic has one answer, but a lot of my own students have another:

“Your course [in social anthropology] has profoundly influenced my path over the last 7 years: I’m currently a student midwife at Ryerson University, Canada, and think back often to the critical and curious lens that your teaching afforded me… In my work, political life, and student life, I work to ground myself in the engaged critical practices I was lucky enough to learn from professors like yourself…I really credit your course as an important part of why I do the work that I do!

– Unsolicited email, Alumna, 2009

In fact, dear Critic, it is thanks in fact to these very (critical thinking) skills, that our students have been so quick to place your article into its wider socio-political context – an ideological shift towards devaluing the humanities.

In Facebook comments and hallway conversations, many made a clear and disgruntled connection between this article and a bigger trend of “arts bashing”, and jumped to defend their degrees accordingly. One recent BA (social anth) graduate shared:

“I studied damn hard to get my Anth major […] they’re so much harder cause it’s not just straight up facts but looking into things and understanding lots of different ways to see something.”

Another BA(Hons) social anth graduate says:

“clearly no one at critic has actually taken any Anth papers! Easy is not the word I’d use… Diverse and broad based perhaps… I mean where else do you get to cover papers in one subject on medicine, death, reproduction, economics, religion, evil and supernatural forces, globalism and philosophical movements.”

Yet another affirms that the experience hinges on if you “take the time to really make an effort”. Perhaps ‘easy’ is an approach, rather than a characteristic of any one paper or degree.

Graduation 2018: Prof Ruth Fitzgerald standing with BA (Hons) Social Anthropology graduate Jennifer Bell. Jennifer was offered a job at the Ministry of Justice, before she had even finished the year.

So let me encourage and admire all of our past and present students who have worked hard to engage meaningfully with their studies, and who have achieved distinctions like local and international scholarships, and awards for their dissertations and conference presentations. Not to mention all of those marvellous transcripts full of B’s and A’s, achieved through hard work, integrity of purpose, and dedication to the ideals of good scholarship.

I think it’s easy to see the difference.

Yours Sincerely

Prof. Ruth Fitzgerald

Social Anthropology Programme, School of Social Sciences

Red flag waving: Medical crowdfunding trends show the precarity of kiwis in Australia is not just a Covid-19 issue

Posted on by smisu13p

Covid-19 has put an enormous strain on New Zealanders living in Australia, with the Australian government being slow to extend any sort of benefit when lockdowns began in March this year. But the precarity of this group is far from new.

New research on health crowdfunding highlights how wrong things can go, with dozens of families findings themselves reliant on the whims of ‘the crowd’ to support them through dire medical situations, when the state refuses to take responsibility.

Life, death, and the crowd

Donation-based online crowdfunding is an increasingly common way for individuals and families to seek help for various types of need. Health-related crowdfunding is the largest sector of the international platform GoFundMe (which has 80% of the global market share, and takes a tidy percent of all donations) as well as having a major presence on New Zealand’s own non-profit platform Givealittle.

New Marsden-funded research led by Dr Susan Wardell, at the University of Otago, has analysed 574 active campaigns by kiwis both within NZ and overseas, across both platforms, in order to understand who is turning to this means of support, and why. The study found a subset of 44 campaigns were created by Kiwis living in Australia.

Internationally, higher rates of crowdfunding appear in places with weaker formal safety nets; including healthcare coverage, insurance, or social security. Because of this, research into crowdfunding can reveal wider structural inequalities, and in this case the life-or-death implications of questions around benefit eligibility, and citizenship rights, for those who look for a ‘better life’ in Australia.

A better life

The stories and outcomes of the health crowdfunding campaigns in this study, were documented in June 2020 – at the end of New Zealand’s lockdown, but amidst Australia’s ongoing regional restrictions. However, most campaigns pre-dated the pandemic; which is telling in itself

72% of the donation recipients were adults and 28% were children. These are people who experiencing brain tumours, various cancers, heart disease, spinal injuries, spinal injuries, among other issues. The overwhelming majority (77%) were fundraising due to illness, with a handful fundraising due to injuries (9%) or disabilities (7%), and the remaining few campaigns categorised as elective, fertility-related, or mental illness-related. Most campaigns are organised by family members, partners, or friends, rather than the ill person themselves.

Most asked for money to cover direct medical costs, such as hospital care, outpatient medical and diagnostic services, pharmaceuticals, medical or mobility equipment, rehabilitative care and so on.

However, 34% of them also specified the need for help in meeting general living costs, such as household bills, childcare, and transport during times of illness; factors that all have flow on affects for physical health as well. This was much higher than the number of New Zealanders based in New Zealand, who were also crowdfunding, with less than 24% of these requesting help with general living costs.

The lack of access to healthcare and social support, was explicitly stated in two thirds of the campaigns, as the reason for their need:

Multiple cases mentioned working and paying taxes in Australia long term and still not being able to access meaningful supports. For example, while one family had “lived and worked” in Australia for eight years, they were unable to access any social welfare when the father was diagnosed with a brain tumour. Another campaign tells the story of a terminally ill man residing in Australia for 18 years but still has no access to support. In the campaign his family states he is not “allowed” to become a citizen now because of his diagnosis, but also that is unable to return to New Zealand for treatment because supports are no longer available to him after living in Australia for such a long time.

Citizenship struggles

In 2001 policy changes implemented in Australia saw that New Zealanders living there would stay on an indefinite visa, rather than gaining citizenship. While New Zealanders have access to emergency care under this system, any long term and ongoing treatments are not covered. This includes doctors visit and pharmaceuticals. It also limits access to welfare and social support.

Furthermore, marriage to an Australian citizen does not grant citizenship and the subsequent benefits of affordable healthcare and social support. Those married to Australian citizens still were unable to access welfare and health care assistance, while living in Australia with their partner (even if they were working themselves). This means that individuals are faced with potentially uplifting their lives back to New Zealand to receive the treatment needed, even though their lives are embedded in Australia.

Children and families

Though crowdfunding presents individual stories, designed for public attention, very few are about individuals alone. Family members are more than not implicated in the difficult sets of laws around citizenship and welfare access.

Children born in Australia to New Zealand citizens must reside in Australia for 10 years before they are citizens. This means they are ineligible for supports. For kiwi families living and working in Australia, whose young children have medical needs, this rule can have severe impacts. For example, one campaign was for an 18month old child with a serious neuromuscular disorder, who was born in Australia, to parents who are New Zealand citizens. Though he is eligible for “life-saving treatment” through the government, they explain he needs further help for costs he is not eligible for help with, including the therapies, and equipment, that might enable him to one day crawl or walk.

Crowdfunding campaigns typically involve narratives crafted to present ‘deserving’ individuals as worthy recipients of donations. Overseas studies have shown this typically takes the attention away from systemic issues. The campaigns we studied were atypical in that, to explain their situation and justify asking for help, they often went into detail about the systems they were caught within:

Both these examples reflect the fact that if parents of a child are New Zealand citizens, even if the child was born in Australia, they still do not have access to supports and affordable healthcare for that child. This is in stark contrast to what Australians living in New Zealand receive. It shows the high degree of awareness of the campaigners to the systems they are caught within, but have no opportunity to change or contest.

Unequal exchange

The benefits extended to New Zealanders living in Australia are vastly less than those that apply to Australians living in New Zealand. This has been the focus of an ongoing campaign by Oz Kiwi, a small team of volunteers governed by a committee, whose purpose is “campaigning for the fair treatment of New Zealanders living in Australia”. They provide the following, striking graph about the disparities…

Figure 1: ‘Rights comparison’, from the OzKiwi fact sheet, October 2016. http://www.ozkiwi2001.org/2016/05/oz-kiwi-factsheet/

In 2017, in response to census data researchers also pointed to inequality and discrimination against New Zealanders living in Australia. They also suggested that these measures appear to be specifically targeting Māori and Pasifika immigrants, with less than 3% of immigrants from New Zealand who take up citizenship being Māori. OzKiwi also suggestion that single mothers are disproportionately affected by this process.

Covid19 has brought the inequalities to media attention in new ways. In March New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern had to publicly and repeatedly request that the Australian Government provide supports for the Kiwis stuck in Australia during the pandemic – and struggling with job losses, and subsequent loss of incomes – in the same way that New Zealand was providing care for Australian citizens stuck in New Zealand. The eligibility of Kiwis for the Australian ‘Jobkeeper’ benefit scheme was eventually agreed. But with the scheme expiring several weeks ago, it is a better time than ever to recognise that the problem is bigger and deeper than this.

Red flag waving

Data on crowdfunding from both before and during Covid19 confirms that kiwis who seek financial assistance from online publics, while living in Australia, are overwhelmingly doing so because they have limited access to formal social supports.

Is it right that they should have to do so?

Crowdfunding is ultimately an unreliable form of meeting what are sometimes life-or-death needs – shown in much existing data to fail to reach its financial goals more often than not. It is a gap-stop at best, and at worst, a red flag waving from the ditch people have fallen into, between Australia and New Zealand, and the safety nets designed not to catch them.

Posted in Case study, Media/political commentary | Tagged australia, benefits, citizenship, Covid-19, Covid19, crowdfunding, health, health crowdfunding, medical anthropology, medical care, medical crowdfunding, migration, New Zealand, precarity, Social anthropology, social security, welfare | Leave a reply