Emmett Till: the photograph that made a martyr, started a movement

Written by Amy Hema, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424.

Emmett Till as pictured at his funeral, in an open casket; deformations the results of the violent nature of his race-based murder.

When thinking about images of evil, this photo immediately comes to mind. I was introduced to it eight years ago, and to me it has always been the epitome of evil.

The photo is of a young boy named Emmett Till, who became a martyr for the US Civil Rights movement after his tragic murder.

But how did one tragedy influence a whole country? With a photograph.

The Murder of Emmett Till

Emmett was a 14-year-old African American boy, who in the summer of 1955 travelled from his hometown [1] Chicago to Mississippi. Before boarding the train, he kissed his mother goodbye, unbeknownst to them both, for the last time.

On August 24th Emmett entered Bryant’s market in the small-town of Money.

The interaction that took place in that store has been debated for decades, but what was reported at the time was that Emmett had been inappropriate with and whistled at the white grocery clerk, Carolyn Bryant [1]

Four days after the alleged incident Carolyn’s husband and his half-brother entered the home where Emmett was staying. They kidnapped, tortured and killed Emmett before tying a cotton gin fan to his neck and throwing his body into the Tallahatchie river, where it would be discovered days later. Emmett’s body had been so badly beaten, the only way to identify him was by his father’s signet ring [1]

Photograph shows the jury at the trial of two white men, Roy Bryant and J.W. Milam, charged with murdering Emmett Till. 9/20/1955. Courtesy: Library of Congress

Roy Bryant and J W Milam were arrested and charged with murder.

They were tried in front of an all-white jury, in a scene Harper Lee herself could have written. After only an hour of deliberation, both Bryant and Milam were found ‘not guilty’[2].

A photo that incensed a nation

I argue that the reason why Emmett became a ‘martyr’, in the sense of his death taking on wider moral and political meaning, is because this photo of his body exists.

Emmett Till was not the first boy to be lynched. At the time, lynching was part of lived reality of African-American communities in the USA [3]. The difference for Emmett is the proliferation of this photograph. This photo exists because Emmett’s mother, Mamie Elisabeth Till-Mobley, made an incredibly difficult decision; to have an open casket funeral. Mamie had to fight for her sons remains to be returned to her, and when she received his remains, she was told the casket had to remain closed [1]

Mamie Till looks stoically over her son. David Jackson (1955). Source: Time: 100 photos http://100photos.time.com/photos/emmett-till-david-jackson NB. In other photos Mamie leans over the casket with an expression of absolute pain and grief.

However, after seeing the horrors that were inflicted upon him, Mamie knew the world had to see what she had seen[4]. The existence of this photo is the enactment of her moral obligation, to a child who could not share his story which needed to be told, and to the world that needed to hear it.

Photos of the body were circulated by Jet Magazine, capturing the brutality of the violence that Emmett had suffered. At the time, these images were circulated within African American audiences only. Being too brutal to publish in mainstream magazines, it would be years before the image became a global phenomenon.

I link this to what anthropologists Kleinman and Kleinman have discussed as the role of suppression in visual representations of suffering[5]. Withholding evidence of suffering denied the public the chance to stand as moral witnesses. The circulation of images like this often by nature only convey one ‘slice’ of a complex reality. However by choosing to not circulate his image, mainstream media outlets were denying and erasing the suffering of Emmett, his family, and the African-American community.

Emmett and the Civil Rights Movement

Kleinman and Kleinman have also argued that images have been used to confront viewers with a moral issue, and call for social action[5]. The photo of Emmett Till is a prime example of moral sentiment being used to rally people toward social justice. Sociologist Joyce Ladner coined the phrase the “Emmett Till Generation” of black activists, to describe the individuals living in the United States who after the death of Emmett Till became heavily involved with civil rights. That term offers a perfect summation of how the image impacted the lives of African Americans[6].

Many consider Emmett’s death and the circulation of the photos to be a catalyst for the civil rights movement, influential activists stated that the death of Emmett had a significant impact on their lives and consequentially their involvement with the civil rights movement. In her memoir, Anne Moody details how the death of Emmett Till made her aware of her own position within society, how after his murder she became afraid of being killed because she was black. Moody went on to describe the rage she felt, at the people who had killed Emmett and the African Americans who, out of fear, stood by and allowed these things to keep happening[7]. Moody’s personal history with the photo demonstrates how moral witnessing, in visual form, not only rallied a generation but created new understandings of how people fit into the world.

Only a few months after the circulation of Emmett’s photo, Rosa parks famously refused to give her bus seat to a white woman, leading to the Montgomery Bus Boycott. When asked why she made that decision she said, ‘I thought of Emmett Till and when the bus driver ordered me to move to the back, I just couldn’t.[4]’

Although Emmett may have not been directly responsible for the civil rights movement, his image was a confrontation of the truth; people could no longer deny that these things were happening and that they could happen to any Black American.

Why does Emmett Till still matter?

Racism still exists within the United States, albeit not in the same way it did 60 years ago. There are no signs separating water fountains or bathrooms. But racism persists in the form of stereotypes, inequality in housing, education and employment opportunities.

Racism in the USA today is the over-representation of unarmed African American teens being killed. Each time there is a killing of a black male in the US, Emmett’s name re-enters the spotlight[8], through his image he has become forever linked with racial violence. Emmett Till was the face of the Black Lives Matter Movement before it existed.

One of the most notorious killings in recent history was that of Trayvon Martin, following the murder of Martin, Emmett Till was once again thrusted into the spotlight. Trayvon and Emmett’s deaths shared a striking resemblance, as the Washington Monthly put it “Separated by a thousand miles, two state borders, and nearly six decades, two young African American boys met tragic fates that seem remarkably similar today: both walked into a small market to buy some candy; both ended up dead.[8]”

The fact that Emmett is still brought up to this day, as a representation of racism and hatred is testament to the power not only of his photo but of images in general, they are lasting, they freeze a moment in time and hold it there. Emmett will never stop being a martyr, because he has been frozen in time as one.

Despite the immense influence of this image, there is still a few glaring questions; sixty years after the circulation of the photo of Emmett, how is it that we are still in the same place? How is it that we are still being bombarded with images of African- American suffering? Have we become, as Frosh put it, desensitised [9]?

We are in a unique period where we can constantly access news and images, in every facet of our lives we are exposed to the suffering of others, but from a position that is so far removed, after a while it becomes harder to empathise. Have we become numb to these killings?

And finally, how many more Emmett Tills will we have to look upon before people change?

References:

[1] See the Documentary: ‘The Murder of Emmett Till’ (2003, PBS).

[2] PBS (n.d.) ‘The Murder of Emmett Till: The Trial of J.W. Milan and Roy Bryant’. PBS: The American Experience. Available at: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/emmett-trial-jw-milam-and-roy-bryant/

[3] In the 75 years leading up to Emmett’s death, it is estimated the over 500 African American’s were lynched within Mississippi, most of them were men accused of associating with white women. https://youtu.be/7uTtNnCw69w?t=426

[4] The Washington Post. ‘Emmett Till’s mother opened his casket and sparked the civil rights movement’. The Washington Post. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/07/12/emmett-tills-mother-opened-his-casket-and-sparked-the-civil-rights-movement/

[5] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. 1996. ‘The Appeal of Experience; the dismay of images: Cultural Appropriations of sufferings in our times.’ Daedalus, 125(1).

[6] Kolin, P.C. The Legacy of Emmett Till

[7] Moody, A. (1968) Coming of Age in Mississippi. Penguin Randomhouse reprint.

[8] Gorn, E.J. (2018). ‘Why Emmett Till still matters’ Chicago Tribune. July 20th. Available: https://www.chicagotribune.com/opinion/commentary/ct-perspec-emmett-till-mississippi-murder-reinvestigation-whistle-white-woman-carolyn-bryant-20180722-story.html

[9] Frosh, P. (2018). ‘The Mouse, the screen and the holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response’, New Media & Society, 20(1), pp351-368.

Hip-hop Dunedin: An ethnographic soundscape

A soundscape produced by Biruk Mengstu, for ANTH210 (Translating Culture)

About the soundscape:

My research question was around the influence of Hip-hop on some students in Dunedin. All these sounds were retrieved from the fieldwork (studio apartment and live underground hip hop showcase) and reconstructed to tell a story of the extent of influence hip-hop has on these students.

My research question was around the influence of Hip-hop on some students in Dunedin. All these sounds were retrieved from the fieldwork (studio apartment and live underground hip hop showcase) and reconstructed to tell a story of the extent of influence hip-hop has on these students.

About the ANTH210 process:

Throughout my high school and university life, I have always been interested in the natural science field. However, I have always wanted to learn more about my surroundings and the social science aspect. When I found out about the ANTH210 paper, I thought it would be an excellent opportunity to challenge myself and to get out of my comfort zone as I have never taken an anthropology paper before.

This paper has opened my mind to a different way of thinking and has shown me that there are so many different cultures that are all around which we sometimes don’t realise. This paper has allowed me to get in touch with my creative side, which I never really had the chance to express before. Overall I enjoyed and learned a lot by being a part of the Anthropology 210 (Translating Culture) class.

The Smell of Suffering: Portrait of a Street Boy

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Street photographers visualise social suffering through their artwork. They engage (themselves and us) with unfamiliar experiences: shrinking cities, strange portraits. Photographers can function as both moralists and anthropologists. They are often spectators, often self-exiles – presenting a version of evil for others to interpret, but often also fulfilling their own sense of moral obligation.

My argument is that both the positionality of the street photographer, and the medium of the photograph, means that photos sometimes break free from the time and space, conveying a universalism of personal adversity. I use an example of street photography of homeless in Moscow to discuss this.

Down and Out

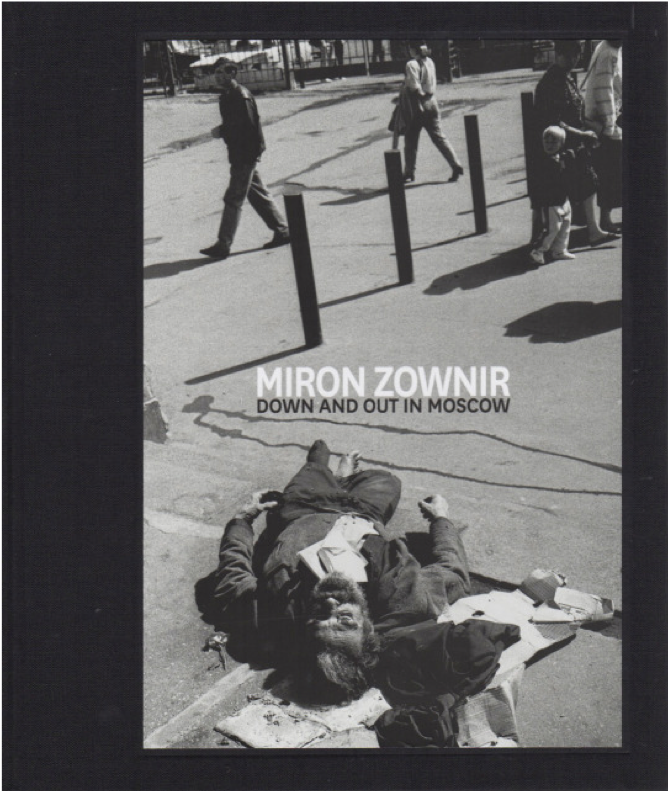

German photographer Miron Zownir is one of the most radical contemporary examples. His focus on marginal characters and the dark side of cities is rooted in his childhood. A Ukrainian-German who grew up in post-war Germany, Zownir as a teenager immersed himself in Eastern European literature without trusting any existing political systems or social stereotypes. His inherent interest in individualists inspired him to live in slum-like places, capturing streets with an anti-establishment attitude.

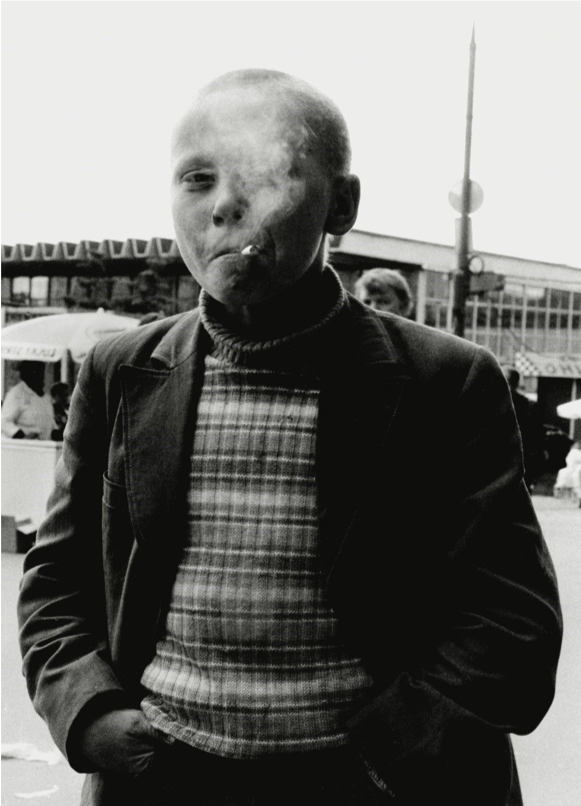

The street portrait is from Miron Zownir’s publication Down and Out in Moscow, a series of images that captured the homeless crisis in the Russian capital in 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I noticed the smoking boy with an adult expression to his cynical appearance when I first came across it in 2018. It is somehow different from the other challenging photos in his book. Momentarily, the encounter between Miron Zownir and the boy constructed a story about how individuals were abandoned by society. The diffusing cigarette smoke in front of the boy seems to allow me to smell the evil that permeated the city.

Kleinman & Kleinman (1996)[i] discuss the moral implications of photographs, through contextualising engagements within creators, audiences and images.

Zownir’s photographic experience runs through the technical transition: turning from black-and-white film to digital photography in the post-modern era. This photo was captured in a classic form, of black and white portraiture displayed in gallery spaces, and print journalism (books, and magazines). But it is worth noting that the extended agency of photographs can shift, depending on medium, from a momentary, regional realm to a worldwide standing discussion, through different forms of reprinting and representing.

How different would the viewers experience of this boy’s suffering be, scrolling past a small version in a social media feed? Touching his face on a tablet?

Moral Obligation in Street Photography: Unperceived Suffering as Social Experience

Anthropologists may ask: what is the basis of a photographer’s sense of moral obligation to take photos on streets?

Street photography concentrates on people and their behaviour in public, thereby also recording personal history: though without formal consent, and with the combination of spontaneity, outsider perspective, and private exploration. These subjects of circumstances are generally unaware – either stared at or ignored until they were documented. Street photography uses these collected narratives to define cultures or places, with no duty to serve a larger whole, and no limitation on how they reconstruct these places[ii].

Kleinman & Kleinman considered that photographers represent individual suffering as part of social experience, for others to access – whether these are extreme or ordinary forms of suffering. But as anthropologists, they caution that “there is no timeless or spaceless universal shape to suffering,” (1996, p:2).

In Down and Out in Moscow, Miron Zownir photographed death, sin, and a harsh lived reality. Underlying the powerless state, the rampantly violent proliferation pushed Moscow to become a hotbed of criminal forces in the 1990s; “the most aggressive and dangerous city, … people were dying right there on the street”.[iii] Such tension immediately changed Zownir’s original mission: to document Moscow’s nightlife with three-month project funding from a photographic committee.

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience, and Kleinman & Kleinman suggest that moral witnessing also must involve a sensitivity to others, albeit with unspoken moral and political assumptions. Still functioning as a photographer, Zownir did not tend to query the government, or alter Moscow residents’ condition – but instead chose to live briefly in this shadowed twilight zone, to experience the nightmare.

Individual into the Universal: Reflexive Appreciation against the Silent Oblivion

How can we perceive a stranger’s suffering as universal? Here, a street boy’s sophisticated body language is beyond verbal expressions: dressing in a suit over a horizontal striped turtleneck sweater, his hands are hidden in his pants pockets like a social youth. He looks indifferent to the surroundings and unmoved by the photographer. He is clothed, unlike many beggars, and yet he was banished to a community where no-one had a home.

This portrait reminded me of the 1994 film In the Heat of the Sun. The film is based on Chinese writer Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, which is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, and tells how a teenage boy and his friends are free to roam the streets day and night in a period in which all the social and educational systems are extremely non-functional. Both protagonists are undergoing suffering – the film an example of the way their individual experiences can be abstracted and universalised, for the consumption of a wide variety of audiences. Yet this this also shows us how images and films can provide an insight into personal suffering that is usually invisible – although the harsh realities behind the lives they represent often go on unchanged.

The unwitting suffering of Zownir’s street boy is entangled with the political unrest in Moscow. But as a photograph, it also exists apart from the historical context: “a professional transformation of social life […] a constructed form that ironically naturalised experience.”[iv]

The frame itself cannot communicate this context. Yet it can communicate something else – the universality of human feeling event amidst diverse and ethically incommensurable [v] societies. Perhaps this is the power of portraiture – indeed the seminal psychological research of Ekman, and others, has asserted that emotional expression on faces is universal [vi] – meaning that moods and feelings may at times transcend cultural limitations, an idea often grappled with in the anthropology of emotion.

Conclusion: photography as a container of truth and imagination

Miron Zownir wrote in his poetry: When the earth returns with a thousand sunsets, the truth of the universal is darkness.[vii]

Photography blurs social facts, but seals emotions. Whether the boy would recognise the chaos, ignorance and madness that Zownir’s book communicates, in his free childhood in post-collapse Moscow, cannot be known. Yet seeing this photo as a cultural artefact, we can recognise that both the photographer and the audience as complicit in reproducing and politicising fragmented histories in photography. The photograph becomes a container for these forms of imagination.

Several years later after this photo was taken, when Miron Zownir was back in Moscow for his upcoming exhibition, the city’s exterior had been cleaned up. The silent responses of audiences standing in front of an enlarged version of this photograph, seemed at a vast remove from its original context. What meaning, what comfort, did it hold then? Yet the world still calls for images, as ‘the mixture of moral failures and global commerce is here to stay’ (Kleinman & Kleinman 1996: p. 7).

References:

[i] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[ii] Levy, S. (2019) ‘Street photography as a process’ in Lens Culture Guide to Street Photography, pp. 8-12

[iii] Zownir, M. (2014) ‘I was always an individualist’, Berlin Interviews, by Katerina, http://berlininterviews.com/?p=1375.

[iv] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[v] Fassin, D. (2009) ‘Beyond good and evil?: Questioning the anthropological discomfort with morals.’, Anthropological Theory. Sage, 8(4), pp. 333–344.

[vi] Ekman P, Friesen W (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press : Palo Alto.

[vii] Zownir, M. (2018) ‘Black’, Vision

Women ‘blue’ and bleeding: Witches in contemporary East Indonesia

**Originally published on the ANTH424: Anthropology of evil blog, 22nd June 2018**

Written and visual accounts of witches have changed dramatically across cultures and time. Witches were once described by Europeans in the sixteenth century as old and evil, with wrinkled and deformed features, and are now being depicted in contemporary popular culture as feminist figures who have a pale complexion, and are glamorous and beautiful [1][2]. The visual traits of contemporary witches of East Indonesia are quite distinct from what we encounter in these European historical accounts and in popular culture.

Witches, known as dukun in Indonesia have played a fundamental role in the lives of many East Indonesians, and have impacted how they structure their communities[3]. In this post I analyse how their visual traits and characteristics relate to Mary Douglas’s[4] ideas about the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution. Douglas argues that the body is a symbol of society that requires order and classification, and by referring to East Indonesian witches, one can distinguish this.

In some areas of East Indonesia, there are no distinct visual traits that set apart witches within their communities. Konstantinos Retsikas ethnography [3] concerning sorcery in East Java, Indonesia, noted that both the instigator and the sorcerer remain hidden in fear of being killed. People can only rely on rumours and whispered accusations to identify witches within East Java. As a witch, blending in is the safest approach. At the same time, they share the same motives of envy, greed and jealousy that is common in everyone, challenging people’s ability to accurately recognise the witches within their community.

In some areas of East Indonesia, there are no distinct visual traits that set apart witches within their communities. Konstantinos Retsikas ethnography [3] concerning sorcery in East Java, Indonesia, noted that both the instigator and the sorcerer remain hidden in fear of being killed. People can only rely on rumours and whispered accusations to identify witches within East Java. As a witch, blending in is the safest approach. At the same time, they share the same motives of envy, greed and jealousy that is common in everyone, challenging people’s ability to accurately recognise the witches within their community.

Although due to this lack of distinct visual traits, Retsikas found that in East Java sorcery accusations always tend to focus on one’s relatives, neighbours, friends and work colleagues. Convivial intimacy is risky and choosing one’s friends wisely is critical. Hence, their unidentifiable traits protect some witches, but also leads to uncertainty and moral panic amongst the people of East Java. The unmarked body of witches impacts the communities ability to keep things pure and in order, affecting how members of East Java respond to one another in times of conflict. Thus, this reflects on Douglas’s idea concerning how the body, whether marked or unmarked, is a key symbol in identifying how a community functions.

A key trait prominent in Kodi female hereditary witches from the coastal villages of Sumba is their association with “blue arts” [5].

In Janet Hoskins ethnography, she recognised the transformation of Kodi women into witches led to the appearance of the shade blue in and around their body. As she mentioned, “Hereditary witches have “blueness in them”, they are “bluish people” (tou morongo) whose very blood is believed to be in some way poisonous to others… Blueness is said to be deep inside the liver (ela ate dalo) of a witch, a kind of poison that can affect others even without her willing it” [5]: 322. This poisonous trait is a reflection of pollution and signifies the darkness within hereditary witches. When they are exposed to this powerful trait that can harm the community and their formal structure, it pushes witches into the margins. “Blue arts” or “blueness” found internally and externally in hereditary witches sets them apart from other Kodi women, making them vulnerable to discrimination by their community, and powerful at the same time. Thus, their polluting body has the potential to disrupt the communities social structure and create fear amongst people.

Menstrual blood is a powerful characteristic associated with witchcraft.

Both Konstantinos Retsikas and Janet Hoskins ethnographic study explore the significance of menstrual blood and how the substance has impacted how some villages in East Indonesia function today. In the Huaulu community, Hoskins found that they have strict menstrual taboos to protect their people. Menstruating women are required to stay in menstruating huts away from the men until their cycle has finished. Menstrual blood is believed to be a dangerous and contaminating substance of witches, and can lead to men becoming extremely ill if they come in contact with it. Hence, Huaulu women accept this menstrual taboo as it is seen as a way of protecting the men within their community, and keeps their village pure and clean.

Huaulu strict taboo and the significance of menstrual blood for many other East Indonesian villages relates to Mary Douglas’s idea about the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution. According to Douglas, “The body is a model which can stand for any bounded system”[4]: 115. The bounded system in Huaulu expresses anxiety about the body and its fluids, while at the same time it administers care and protection for the group. Some argue that specific parts of the body, particularly menstrual blood symbolises “dirt [that] offends against order”[4]: 2. Although in Huaulu, their community members are effectively engaging with this polluted and “dirty” substance by creating strict taboos around it, leading to the development of relationships and the strengthening of social order. Therefore, the significance of menstrual blood and its association with witches impacts how Indonesians culturally construct their communities.

Although there are no distinct traits that set apart Indonesian witches in some areas, they continue to play a fundamental role for numerous citizens. Their presence within key substances, and power to cause positive change and conflict within one’s life does not go unnoticed. At the same time, their features relate to Mary Douglas’s ideas of the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution in many ways, affecting how people of East Indonesia function in contemporary society.

Written by: Pulegaomalo Muliagatele-Carter

References:

[1] Briggs 2002: p.15 in Mencej, M. (2007) ‘7- Social Witchcraft: Village Witches’. In: Styrian Witches in European Perspective: Ethnographic Fieldwork, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 313-346.

[2] Buckley, C. (2017) ‘Witches in Popular Culture’. [online]. The Open University. Available from: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/literature/witches-popular-culture. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

[3] Retsikas, K. (2010) ‘The Sorcery of Gender: Sex, Death and Difference in East Java, Indonesia’. South East Asia Research, 18(3), pp. 471-502.

[4] Douglas, M. (1966) Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge and K. Paul.

[5] Hoskins, J. (2002) ‘The Menstrual Hut and The Witch’s Lair in Two Eastern Indonesian Societies.’ Ethnology, 41(4), pp. 317-333.

We are ritual creatures

The 3 Minute Thesis competition is a lively annual event. This year Marshall Lewis, a Phd student in Otago’s Social Anthropology programme, competed in the University finals. We thought we’d share the content of his excellent presentation on ‘Ritual Design’ with you! …

“If you have goals that are important to you – and I bet you do – then you may want to design your rituals to support your goals. That’s the main idea behind my project.

So, very quickly: what do I mean by ritual, why use it and how might we design ritual?

Marshall Lewis delivering his presentation

Think of rituals as actions that embody and express your beliefs and values – you live your beliefs and values through ritual – perhaps not consciously. You may have waking rituals, hygiene rituals, eating, commuting, working, shopping, pre-game, post-sex, religious ritual – if you’re religious – even binging on Netflix can be ritual-like.

Why is life so ritualised?

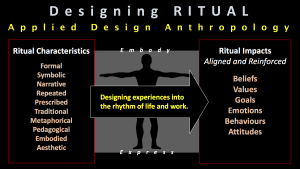

Ritual scholarship is extensive and contentious. I’m focused on two basic propositions: First, there are discernible, family characteristics of ritual – some listed here – and secondly – and here’s why you should care – rituals work. Experimental psychologists have been demonstrating what coaches and drill sergeants have long known: rituals have real impact. For example, they can decrease anxiety, reduce grief, alleviate disappointment. Essentially, they can align and reinforce our beliefs and values.

And knowing that rituals work is real and useful knowledge. What might it look like to take this knowledge seriously: to apply ritual as a strategy or technology to support one’s goals and aspirations? That’s what my project is about. I am applying insights from the interdisciplinary study of ritual — from anthropology, organisational studies and religious studies – to do three things: to defend a conception of ritual as something to be designed; to evolve a practical method for designing ritual, and to apply this method in real-world environments.

Competitors in the 3 Minute Thesis competition are allowed a single powerpoint slide to accompany their 3-minute presentation, and this was Marshall’s image.

Two quick examples: First, I work in a large company that wants a collaborative culture, where people feel empowered to shape the future of the organisation. The question becomes: How might we design organisational rituals such as team meetings and problem-solving sessions if our goal is a collaborative culture?

Secondly, my youngest daughter is starting law school later this month, and she’s designing rituals to help maintain a healthy lifestyle during that period of intensity.

The ritual design method is straight forward, although far from easy. First, clarify your goal and the beliefs and values you want to reinforce (easier said than done!). Then, you design your rhythms and activities using the key characteristics of ritual as design principles. It’s a creative process, though analytically derived.

We are ritual creatures. Ritual is one of the key strategies humans use to bring some order and method to the challenges and chaos of life.

Good luck with your goals! And consider how your rituals can support you!”