Juan Gomez writes…

You will probably recognize the following phrase: ‘An attempt to introduce the experimental Method of Reasoning into moral Subjects.’ It is the subtitle of David Hume’s Treatise of Human Nature of 1739-40, and the first explicit mention of the application of the experimental method in moral topics. Many scholars have pointed to it, and claimed that Hume was the first one to go forward with this attempt. However, others (Tom Beauchamp, Alexander Broadie) have also noticed that this idea did not originate with Hume. I will show here that the ‘spirit’ of the experimental method was very much alive at least 20 years before the publication of Hume’s Treatise. In fact, contrary to the most commonly held view, Hume should not be the reference point when studying the emergence of the “science of man”. Rather, we should look at the Aberdeen philosophers, in particular at George Turnbull and his lectures at Marischal College in the 1720’s.

I will make a prima facie case for this claim with only a few quotes (available in this document), but please do contact me if you are interested in the topic, since there is more than enough evidence that I would be happy to discuss with you.

To begin with, Hume was not the first to allude to the application of the experimental method in moral philosophy. Francis Hutcheson had already done this in his 1725 Inquiry. The subtitle of this work explains that it contains the following:

- the Principles of the late Earl of Shaftesbury are explained and defended against the Fable of the Bees; and the Ideas of Moral Good and Evil are established, according to the Sentiments of the Ancient Moralists, with an attempt to introduce a Mathematical Calculation on subjects of Morality. (emphasis added)

Hutcheson doesn’t use the words ‘experimental method’, but saying that he will give a ‘mathematical calculation on subjects of morality’ is perfectly in line with the spirit of the experimental method (specifically with the Newtonian method). To be fair to Hume, he does recognize Hutcheson as one of the philosophers who has “begun to put the science of man on a new footing.” (Treatise (1739), Introduction, p. 6-7) So Hume might have recognized that he was not the first, but a number of modern scholars have not.

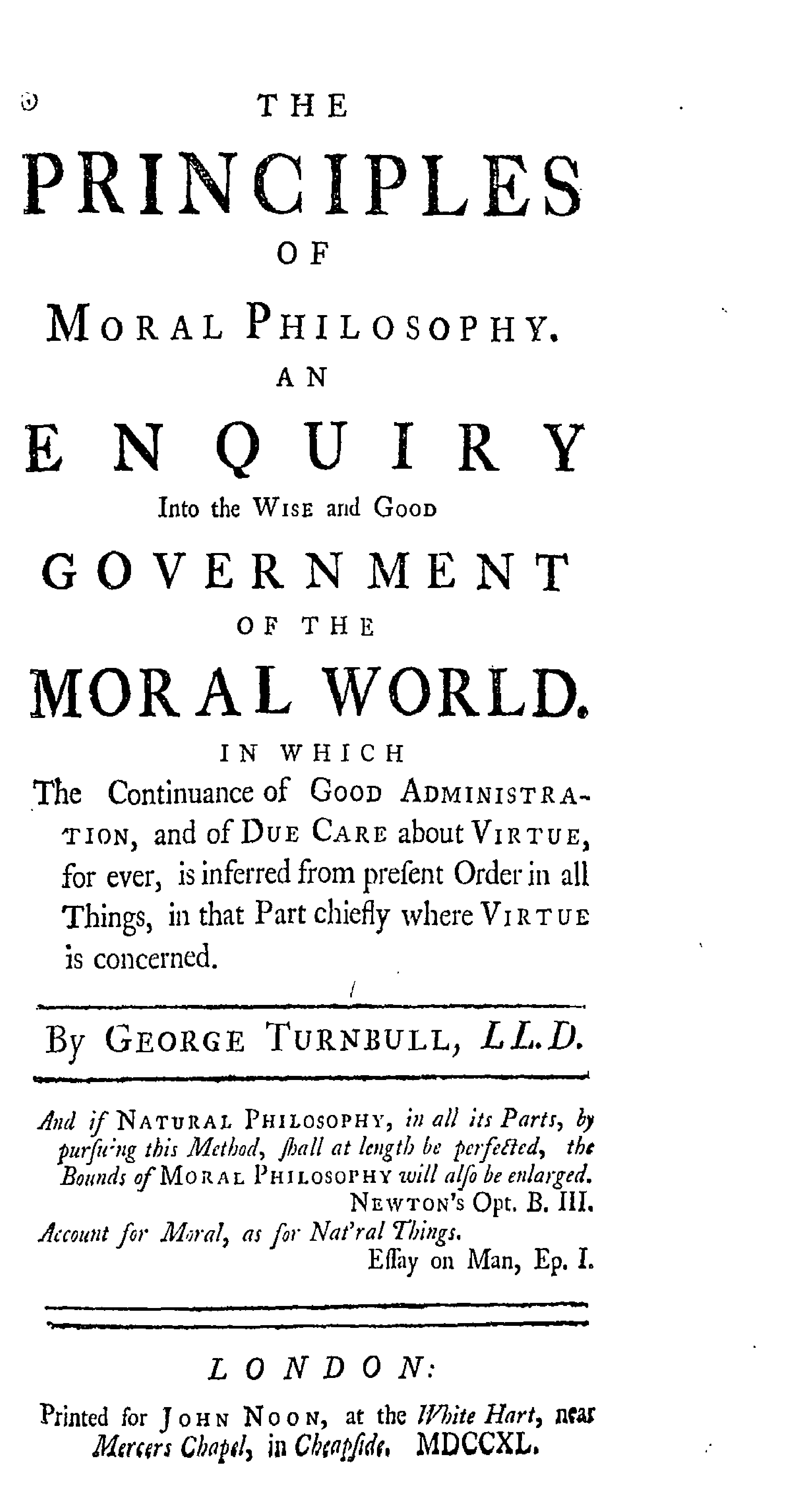

Moving on to George Turnbull, whom I believe is mistakenly underrated as a figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, published his Principles of Moral Philosophy in 1740, the same year Hume published the third volume of his Treatise, which is on Morals. This would at least lead us to think that both Hume and Turnbull were working on the application of the experimental method in morality at the same time. But as Turnbull mentions in the introduction to his Principles, his book is based on the lectures he gave at Marischal College between 1721 and 1726, around the time when Hume was a student at the University of Edinburgh. Besides the numerous remarks in the Principles that show Turnbull’s devotion to the experimental method, there is a key document that shows that he was teaching the young Aberdeen students the moral philosophy he explains in the book he published 17 years later. The document is the 1723 graduation thesis, which the graduating students (Thomas Reid among them) had to defend, titled De scientiae naturalis cum philosophia morali conjunctione (On the unity of natural science and moral philosophy).

I am currently working on the 1723 thesis, and at this moment I can let you know that it is strengthening my belief in the importance of Turnbull in the development of the ‘science of man.’ For now I’ll leave you with enough quotes from the Principles that show that if we want to study the development of the science of morals, we should start focusing more on Turnbull and Aberdeen, and less on Hume and Edinburgh.