The Darker Side of Baconianism

Kirsten Walsh writes…

In my last post, I explained how Newton’s theory of the tides relied on empirical data drawn from all over the world. The Royal Society used its influence and wide-ranging networks to coordinate information gathering along trade routes, and thus construct a Baconian natural history. I pointed out that although the theory of the tides is considered a major theoretical achievement for Newtonian physics it was also a major empirical project and as such it is one of the major achievements of Baconian experimental philosophy. This case, however, also highlights how the Royal Society exploited its connections with politics and economics in pursuit of knowledge to benefit an elite monied class. In this post, I’m interested in exploring the connections between the Royal Society’s epistemic achievements and its being embedded within the political structures of the early modern world, particularly the rise of large trading empires.

If Bacon is considered to be the ‘Father of Modern Science’, then it’s worth reflecting on the nature of his legacy, and the role Baconianism played in shaping modern science. It is often tempting to split the objectivity and purity of science from the often complex, difficult, morally ambiguous world. In the same vein, reflections on the Royal Society and the birth of modern science often ignore the essential enabling role played by other of the British Empire’s activities: exploitative trade and slaving. Present-day philosophers of science increasingly reject the ‘value-free ideal’, recognising that scientific practice is best understood within its social, institutional and political context. If what are traditionally conceived of as non-epistemic values play an inextricable role in, say, modern medicine, then they likely do here as well. In this post, I’ll apply these ideas to the case of the tides, suggesting that it highlights a darker side of Baconianism.

The collection of tidal data was carried out by the Royal Society in cooperation with the Royal African Company and the East India Company. (When he discusses the Tonkin tides, for example, Newton appeals to data obtained by Francis Davenport, Commander of the Eagle—an East India Company vessel.) Both the Royal African and East India Companies engaged in extractive behaviours in their respective localities; extractive behaviours we now consider morally abhorrent (most strikingly the slave trade in Africa). While the Royal Society cannot be considered responsible for these acts, we might say that it played a role in legitimising, normalising and even celebrating them.

Indeed, these close ties between science and trade were present from the very inception of the Royal Society. The Royal Society and the Royal African Company received their second royal charters in the same year (1663) and were often thought of as sister companies. Thomas Sprat highlights these ties in his History of the Royal Society:

[I]f Gentlemen ‘condescend to engage in commerce, and to regard the Philosophy of Nature. The First of these since the King’s return has bin carry’d on with great vigour, by the Foundation of the Royal Company: to which as to the Twin-Sister of the Royal Society, we have reason as we go along, to wish all Prosperity. In both these Institutions begun together, our King has imitated the two most famous Works of the wisest of antient Kings: who at the same time sent to Ophir for Gold, and compos’d a Natural History, from the Cedar to the Shrub (Sprat, 1667: 407).

The two companies received their royal charters very soon after Charles II’s coronation. And both were held up as symbols of the Restoration—promises of prosperity to come. Sprat measures the success of the Royal Society largely in terms of its ability to exploit the trade network, praising the “Noble, and Inquisitive Genius” of English merchants (Sprat, 1667: 88). He writes:

But in forein, and remote affairs, their [i.e. the Royal Society Fellows’] Intentions, and their Advantages do farr exceed all others. For these, they have begun to settle a correspondence through all Countreys; and have taken such order, that in short time, there will scarce a Ship come up the Thames, that does not make some return of Experiments, as well as of Merchandize (Sprat, 1667: 86).

Sprat links the success of the Royal Society to its ability to exploit the trade networks; rhetoric which might have lent legitimacy and integrity to other actions carried out in the name of British supremacy.

Further, the direction of research reflected the economic and political interests of these trading companies. A history of tides was one of the projects suggested by Bacon in the appendix to his Novum organum, and as such, it is not surprising that the Royal Society committed resources to this project. However, the Royal Society could not have carried out this project without the support of British trade. A Baconian history of tides was necessarily a large-scale affair: information needed to be gathered from all over the globe. It wasn’t until the 17th century, when British trading companies sent ships all around the world, creating networks of merchants, priests and scholars, that such a project was even possible. But the knowledge that was produced was facilitated by, and in service of, those interests.

English, Dutch and Danish factories at Mocha (1680)

As global trade increased, knowledge of world-wide tidal patterns became increasingly important. European trading companies vied with one another for footholds in Africa and Asia and engaged in sea battles to gain political control in these regions (most notably the Anglo-Dutch Wars). Knowledge of tidal patterns was important both at sea, where failure to account for tidal flow could lead to navigation errors, and in narrower rivers and harbours—approaching a harbour with a shallow bar at low tide could mean a costly delay or worse. And so, the increasing importance of the tide problem and its increasing tractability stemmed from the same cause. Or, to put it another way, the direction of research was both enabled by, and carried out in the service of, the economic and political aspirations of British trade. In short, the trading empires did not merely enable the success of Newton’s work on the tides and other Royal Society projects; rather, they often directed and shaped them.

What conclusions should we draw from this? It comes as no surprise to historians, philosophers and sociologists of science that knowledge-production and the rest of society—including its exploitative, oppressive activities—are interwoven. However, the connection between natural philosophy and exploitative trade is only rarely made in presentations of the Royal Society’s work or Baconianism generally. Instead, science is often viewed as floating serenely and objectively above the darker aspects of early modern society. (This is surprising, given such rhetoric as Sprat’s.) But this case suggests that the Baconian requirement of information-gathering on a massive scale was enabled by—and perhaps itself worked to legitimate—the systems of trade which, often, represented the darkest parts of Western Europe. This is not to say that the Royal Society explicitly endorsed these features of the early modern world. Rather, the success of such large-scale Baconian projects may have tacitly whitewashed the social and political context.

What value is there in this sort of project? You might worry that, by casting a morally critical eye on the period, I lose my historian’s objectivity, believing myself to be coming from a position of superiority and moral maturity: a dangerous way to do historiography. Regardless of what objectivity might amount to in this context, I think it would be a mistake to couch the project in these terms. Rather, I am interested in what such cases can teach us about the nature of science, the value-free ideal and the role of value in science more generally. As such, this initial analysis leaves me with a few questions: Firstly, was the tidal data sullied, morally and/or epistemically, by the context of its collection? Secondly, if this data was morally sullied, were Newton and the others morally wrong to use it? Finally, what effect should this case have on our lauding of the early Royal Society as an exemplar of good science? How we eventually answer these questions at least partly depends on whether we think that the context of inquiry undermines the epistemic value of the project. In my next post, I’ll explore the idea that the epistemic injustice committed by the Royal Society in the name of Baconianism should undermine its status as exemplary.

Natural Histories and Newton’s Theory of the Tides

Kirsten Walsh writes…

Lately, I’ve been thinking about Newton’s work on the tides. In the Principia Book 3, Newton identified the physical cause of the tides as a combination of forces: the Moon and Sun exert gravitational pulls on the waters of the ocean which, together, cause the sea levels to rise and fall in regular patterns. This theory of the tides has been described as one of the major achievements of Newtonian natural philosophy. Most commentators have focussed on the fact that Newton extended his theory of universal gravitation to offer a physical cause for the tides—effectively reducing the problem of tides to a mathematical problem, the solution of which, in turn, provided ways to establish various physical features of the Moon, and set the study of tides on a new path. But in this post, I want to focus on the considerable amount of empirical evidence concerning tidal phenomena that underwrites this work.

Let’s begin with the fact that, while Newton’s empirical evidence of tidal patterns came from areas such as the eastern section of the Atlantic Ocean, the South Atlantic Sea, and the Chilean and Peruvian shores of the Pacific Ocean, Newton never left England. So where did these observational records come from?

Newton’s data was the result of a collective effort on a massive scale, largely coordinated by the Royal Society. For example, one of the earliest issues of the Philosophical Transactions published ‘Directions for sea-men bound for far voyages, drawn up by Master Rook, late geometry professour of Gresham Colledge’ (1665: 140-143). Mariners were instructed “to keep an exact Diary [of their observations], delivering at their return a fair Copy thereof to the Lord High Admiral of England, his Royal Highness the Duke of York, and another to Trinity-house to be perused by the R. Society”. With respect to the tides, they were asked:

“To remark carefully the Ebbings and Flowings of the Sea, in as many places as they can, together with all the Accidents, Ordinary and Extraordinary, of the Tides; as, their precise time of Ebbing and Flowing in Rivers, at Promontories or Capes; which way their Current runs, what Perpendicular distance there is between the highest Tide and lowest Ebb, during the Spring-Tides and Neap-Tides; what day of the Moons age, and what times of the year, the highest and lowest Tides fall out: And all other considerable Accidents, they can observe in the Tides, cheifly neer Ports, and about Ilands, as in St. Helena’s Iland, and the three Rivers there, at the Bermodas &c.”

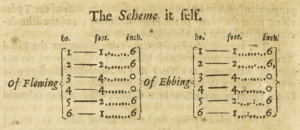

This is just one of many such articles published in the early Philosophical Transactions that articulated lists of queries concerning sea travel, on which mariners, sailors and merchants were asked to report. In its first 20 years, the journal published scores of lists of queries relating to the tides, and many more reports responding to such queries. This was Baconian experimental philosophy at its best. The Royal Society used its influence and wide-ranging networks to construct a Baconian natural history of tides: using the method of queries, they gathered observational data on tides from all corners of the globe which was then collated and ordered into tables.

Newton’s engagement with these observational records is revelatory of his attitudes and practices relating to Baconian experimental philosophy. Firstly, especially in his later years, Newton was regarded as openly hostile towards natural histories. However, here we see Newton explicitly and approvingly engaging with natural histories. For example, in his discussion of proposition 24, he drew on observations by Samuel Colepresse and Samuel Sturmy, published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1668, explicitly offered in response to queries put forward to John Wallis and Robert Boyle in 1665:

“Thus it has been found by experience that in winter, morning tides exceed evening tides and that in summer, evening tides exceed morning tides, at Plymouth by a height of about one foot, and at Bristol by a height of fifteen inches, according to the observations of Colepress and Sturmy” (Newton, 1999: 838).

I have argued previously that Newton was more receptive to natural histories than is usually thought. The case of the tides offers additional support for my argument. Newton’s notes and correspondence show that, from as early as 1665, he was heavily engaged in the project of generating a natural history of the tides, although he never contributed data. And eventually, he was able to use these empirical records to theorise about the cause of the tides. This suggests that Newton didn’t object to using natural histories as the basis for theorising. Rather, he objected to treating natural histories as the end goal of the investigation.

Secondly, I have previously discussed the fact that Newton seldomly reported ‘raw data’. The evidence he provided for Phenomenon 1, for example, included calculated average distances, checked against the distances predicted by the theory. Newton’s empirical evidence on the tides, as reported in the Principia, was similarly manipulated and adjusted with reference to his theory. Commentators have largely either condemned or ignored this ‘fudge factor’, but such adjustments are ubiquitous in Newton’s work, suggesting that they were a key aspect of his practice. Newton recognised that ‘raw data’ had limited use: to be useful, data needed to be analysed and interpreted. In short, it needed to be turned into evidence. The Baconians appear to have recognised this: queries guide the collection of data, which is then ordered into tables in order to reveal patterns in the data. As this case makes clear, however, Newton’s theory-mediated manipulation of the data went beyond basic ordering, drawing on causal assumptions to reveal phenomena from the data.

Thirdly, this case emphasises Newton’s science as embedded in rich social, cultural and economic networks. The construction of this natural history of tides was an organised group effort. That Newton had access to data collected from all over the world was the result of hard work from natural philosophers, merchants, mariners and priests who participated in the accumulation, ordering and dissemination of this data. Further, the capacities of that data to be collected itself followed the increasingly global trade networks reaching to and from Europe. Newton’s work on the tides was the very opposite of a solitary effort.

On this blog, we have noted in passing, but not explored in depth, the crucial roles played by travellers’ reports and information networks in Baconian experimental philosophy. Newton’s study of the tides is revelatory of the attitudes and practices of early modern experimental philosophers with respect to such networks. I shall discuss these in my next post.