Locke’s proofs

Peter Anstey writes…

Many experimental philosophers were committed to the view that a science of nature would ultimately be a demonstrative science. In other words, natural philosophy should be a form of scientia based upon propositional axioms or first principles and derived via demonstrative reasoning using syllogistic logic.

This feature of much early modern experimental philosophy provides a problem for those who interpret it through the rationalism/empiricism distinction. For, it seems to be a characteristic of rationalist philosophers that they aim for the demonstrative ideal whereas the so-called empiricists, it is claimed, opted for a form of probablism. And yet many so-called empiricists were committed to the demonstrative ideal.

One such philosopher was John Locke. Interestingly, however, Locke developed his own theory of demonstration that was based upon his theory of ideas and not upon the Aristotelian conception of scientia. Locke claimed that demonstrative knowledge is not knowledge derived from true propositions but rather the perception of the agreement or disagreement of two ideas with the assistance of a third, intermediate, idea (Essay II. xvii). As such Locke’s theory of demonstration was pre-linguistic (that is, it doesn’t have to do with statements that are capable of truth or falsity), even though he freely admitted that the transition to verbal expression of these thoughts is irresistible (Essay IV. v. 3–4).

Now, Locke called his intermediate ideas proofs (Essay IV. xvii. 2). This seems to be a rather odd use of the term ‘proof’ in early modern English. It does not appear in the OED and it may be thought to typify a theory that was unusual or even idiosyncratic. It seems, however, that there might have been a precedent for this in English logic.

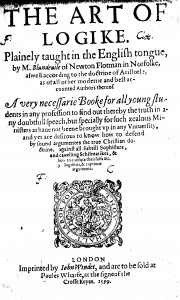

When we turn to Thomas Blundeville’s The Art of Logick (London, 1599, 2nd edition 1617), we find that the middle or mean term in a syllogism is called a proof. Blundeville claims that the major term and the minor term in a syllogism

are made to agree by helpe of a third Terme, called the Meane terme or proofe. (p. 137)

It is interesting to note here not only the use of the term ‘proofe’ for the mean term, but also the claim that the major and minor terms of the premises are made to ‘agree’ by the mean term. Locke’s terminology parallels this very closely, only he applies it to individual ideas like black and white rather than to propositions. For Locke it is the ideas that agree rather than the terms and the proof is the intermediate idea rather than the middle term.

Now, there is, to my knowledge, no evidence that Locke read Blundeville’s Logick and yet Blundeville’s is the only English logic text in which I have found this meaning of the term ‘proof’. So what is the origin of Locke’s terminology? If any readers can shed some light on this I’d be most grateful.

Defending the Scholastics

One of the features of Early Modern Experimental Philosophy was the rejection of the ‘old ways,’ the Scholastic system of philosophy in particular. We have shown in this blog ample evidence of the attack on the Scholastics by those who promoted Experimental Philosophy. We have been showing how the ESD plays an important role in the early modern period, but we have focused mainly on the work of experimental philosophers. In this post I want to present a text that defends the usefulness of the logic of the Scholastics (the use of syllogistic logic in particular). The text is by Edward Bentham (1707-1776), a teacher of divinity in Oxford for twenty years. In 1740 he published Reflections upon the nature and usefulnes of logick as it has been commonly taught in the schools.

In this text, Bentham does not explicitly attack the “new philosophy.” In fact, at some points he recognizes some of the flaws that the promoters of experimental philosophy found in the Scholastics. But his general claim is that those who reject Scholastic logic are making a huge mistake. In the first couple of pages Bentham tells us that most of the treatises in Logic were “wrote in abstruse Scholastic Language,” and these lead the “moderns” to reject “the dry Systematical method of delivering rules.” But these thinkers end up doing more damage by their rejection of Scholastic logic:

- They launch out into various disquisitions upon abstruse subjects; and often draw the illustration of their rules from the depth of other sciences. And by this means, while they seem to enrich the mind with new discoveries, and therefore entertain the Fancy, they perplex the Judgment; While they promise to give the understanding more activity and freedom, they really rob it of that balast, by which in prudence it should be kept steady, and be prevented from being hasty and precipitant in its determinations. Thus enquiries into the nature of our Souls, our Sensations, our Passions and Prejudices, with other springs of wring judgment, make a part of the natural History of Man, rather than a part of Logick, and are of too mixed a nature to fall under general rules.

Bentham seems to be arguing that Scholastic logic should be learnt before exploring any of the other sciences, but this is not to say that the former is all that is needed and the rest of the sciences are useless. On the contrary, they are at the same level: “At the same time that we admire the ingenuity and great learning of later Philosophers, let the exact method and accuracy of the Scholastick Systematical Logicians be entitled to our praise and imitation.” Bentham does admit that there are some flaws in the Scholastic system, but they have nothing to do with the logic. He goes over the different parts of Scholastic logic, and when discussing syllogisms he tells us:

- Now it must be own’d, that in discourse upon ordinary matters, we have no occasion, either to put ourselves to the trouble of continually applying a common standard, or to tie ourselves up to the strictness of Scholastick form, in order to perceive the agreement or disagreement above mentioned [Syllogisms]: Nor can it be any great edification to an inquisitive Student to be told in such variety of form, as sometimes he is in treatises of Scholastick Logick, that Man is Animal. But yet he may find his account in learning those general rules, which are applicable, as a test, to all reasoning, however varied or disguised by the advantage of witty turns and good Language.

Bentham considers Syllogisms to be of great use, and in the final pages of his text he confirms the importance of Scholastic Logic and attacks the moderns who reject it:

- Since the decline of Scholastick learning, though Science of every kind has received prodigious improvements by the labour and sagacity of exalted Genius’s, yet we find the common run of reasoners as bad as ever; –not more knowing, but much more conceited; –not so ambitious as to improve their knowledge, as to conceal their ignorance; –determining magisterially upon points, without knowing or considering the first principles, of what they are discoursing of; –taking themselves to be masters of every subject, upon which they can raise an objection…

In a previous post, Peter Anstey commented on the Straw Man problem for the ESD. But this text by Bentham shows that there was still some appreciation for Scholastic Logic, especially the use of syllogism. Despite all the criticisms of the Scholastic system made by the promoters of experimental philosophy Bentham defended their logic. As Kenneth Winkler points out in his chapter (Lockean logic) in The Philosophy of John Locke: New Perspectives, Bentham was one of the thinkers who attempted to adopt a kind of Lockean logic but without giving up syllogistic. Determining if Bentham was after all (beyond logic) a speculative philosopher requires a lot more than a blog post, but I will keep working on it and follow up on this issue in the near future.