This is the second post in Dr Gerhard Wiesenfeldt‘s series on speculative and experimental philosophy in early modern universities.

Gerhard Wiesenfeldt writes…

In my last post, I wrote about Johann Christoph Sturm’s experimental philosophy and his eclectic approach to speculative philosophy. A very different route to natural philosophy was taken by his colleague and friend, Burchard de Volder. De Volder was professor of philosophy at Leiden University and in 1675 became the first university lecturer to be officially charged with teaching ‘physica experimentalis’. While hardly known today, he was considered an important natural philosopher during his lifetime, he also was a correspondent of Newton, Leibniz and Huygens (who considered him to be the only other Dutchman to have understood Newton’s Principia). When he started teaching at Leiden, he was a clear-cut Cartesian with little inclination for experimental philosophy. He took up experimental philosophy only after the controversies on Cartesian philosophy at Leiden had reached such a level that the university (and in particular the faculty of philosophy) was seriously disrupted in its working. His decision to introduce experimental philosophy was probably motivated both by political considerations (the Cartesians at the university were under serious pressure and de Volder had reasons to fear being expelled) and by the urge to find ways of teaching philosophy that would not lead to conflict and even physical violence. In this he was supported by his conservative anti-Cartesian colleague Wolferd Senguerd, who started teaching experimental philosophy shortly after de Volder had began his lectures.

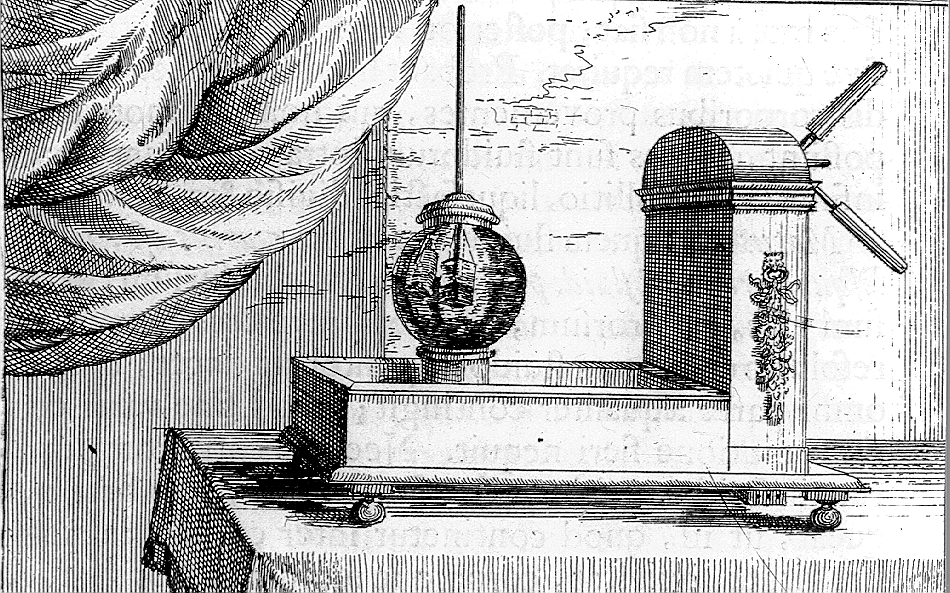

De Volder's airpump as illustrated by his colleague Wolferd Senguerd

While de Volder’s experimental lectures were largely based on Boyle’s New Experiments Physico-Mechanicall with some mathematical splashes from Stevin, he continued to teach speculative philosophy based solely on Descartes’ Principles of Philosophy. De Volder explicitly rejected Sturm’s eclectic approach and argued that speculative philosophy needed to be based on certain, universal principles, such as the Cartesian principle of clear and distinct ideas, in order to create a comprehensive philosophical system. Experimental and speculative philosophy had thus different foundations and remained largely unrelated. Occasionally, there were even contradictions between the two, when De Volder pointed out errors in Cartesian philosophy in his experimental lectures. Still, he maintained that natural philosophy needed to be developed in a systematic way, and that the Cartesian system was the best available.

Yet, over time, his judgment on this matter changed. In the 1690s he argued that Cartesian methodology worked only in the res cogitans, i.e. in mathematics and metaphysics, but not in natural philosophy, as there was no way to establish clear and distinct ideas on the physical world with certainty. While de Volder rejected Cartesian natural philosophy, he did not take up any of the other systems. He remained reluctant about Newton’s Principia and was not persuaded by Leibniz’s attempts to win him over. Instead, he ended up with a methodology not too far from Sturm’s, in stating that one needed to divide the physical world into parts on which certain hypotheses could be developed. He did not elaborate whether this still left room for speculative natural philosophy, but it is hard to see how such a science could have been maintained under these principles.

One of the contentions of these entries on university philosophy relates to the debate in this blog on the experimental/speculative versus rationalist/empiricist distinction. In terms of early 18th century university philosophy these distinctions are on an essentially different level. The distinction between rationalism and empiricism pertains to understanding philosophy as being divided into different schools (or sects). While one might describe rationalism and empiricism as the two biggest philosophical schools (or groups of schools), they were by no means the only ones – one philosopher at Helmstedt University counted no less than 26 different philosophical schools in 1735. The distinction between experimental and speculative philosophy, however, referred to different manners to practise philosophy independent of a particular school. Sturm and de Volder practised both experimental and speculative philosophy, but maintained that they were different enterprises, as did their students Wolff, ’s Gravesande and van Musschenbroek later on. At the same time experimental philosophy transcended philosophical schools, practised by Cartesians, Newtonians, Aristotelians, and Wolffians alike.

2 thoughts on “Speculative and Experimental Philosophy in Universities: (Post-)Cartesianism”

Just for the record: Huygens also thought that Johannes Hudde (then mayor of Amsterdam and Director of Dutch East India Company) was fully capable of understanding the Principia. Hudde was, of course, one of the leading mathematicians of Huygens’ generation of students of Van Schooten.

Fair enough. If I recall correctedly, Huygens’ made this remark around the time when he got involved in various affairs regarding different methods to measure longitude (his own and others), in which he probably wanted de Volder as a strong ally. So, he might have been a bit strong on his praise. In the 1690s there might actually have been a few more Dutchmen who had read and (more or less) understood the Principia.