Aligning multiple images in photoshop

We want images stacked

Sometimes we capture images of the same area (e.g. a particular part of a thin section) using different conditions (reflected light, PPL, XPL, Cathodoluminescence) . We may then want to stack the images together so that we can see how each different mineral, for instance, appears under the different conditions.

THE PROBLEM

We can align objects manually because we see recognisable features in each image. It can be a little tedious and difficult trying to add, manually align, resize and rotate the images in software like: Adobe Illustrator, photoshop, the gimp, image j or other software.

There is a semi-automated way to speed up this process in photoshop. I’m not sure of the exact conditions under which this will actually work. But it’s fairly easy to try and could save you a load of time.

How to do it

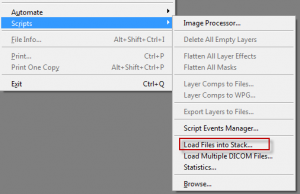

The first thing we need to do is to load all the images as layers in a photoshop document.

- Open photoshop

- Go to file>Scripts>Load files into Stack

- Navigate to the folder with your images in it and load these.

You should now see all your images as layers in photoshop with names corresponding to file names (handy eh?).

- Select all the layers by clicking on the top layer and then shift clicking on the bottom layer. They should all have a blue background in the layers panel indicating they are all selected.

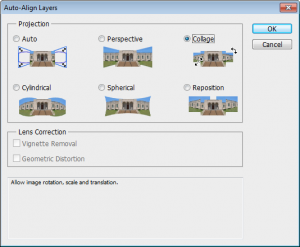

- Now go to edit>auto-align layers

- I recommend trying collage first which will not distort the image.

Thanks to Steve Kidder for working this out with me.

Macro-photography setup

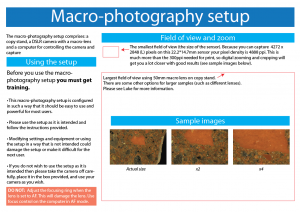

The macro-photography setup in the Geology Department, University of Otago, comprises: a copy stand, a DSLR camera with a macro-lens and a computer for controlling the camera and capture.

What is it for?

Taking photos of samples, specimens etc. close up. The setup has a maximum field of slightly smaller than an A4 sheet of paper. The smallest field of view is the size of the sensor: 22.2*14.7mm. Because you can capture 4272 x 2848 (L) pixels on this 22.2*14.7mm sensor your pixel density is 4888 ppi. This is much more than the 300ppi needed for print, so digital zooming and cropping will get you a lot closer with good results (see sample images in poster below).

Margins for printing

Document types and margins

Typically for text documents such as articles, or reports there will be more than 3mm of white margins all around the documents so there is little need for us to concern ourselves with printer margins. It is only when we create posters, fliers and booklets that we need to consider printing margins.

Margins and professional printing

If we are going to a professional printer then we can create documents that go right up to the edges and they will be able to print these. Sometimes bleed will need to be added (where extra colour is printed around the edges of a document) that is later trimmed off by the printer. The use of bleed ensures that the colour goes right to the edges of printed documents.

Margins for consumer printers that use sheets

Most consumer printers will not print right up to the edges of paper and commonly require around 3mm of margins all around the document. This doesn’t mean that it is necessary to leave 3mm of edges white, if the document has colour right up to the edges then the last 3mm of colour will simply not be printed.

It should be noted that we do not want text to be right up against the margin even if it is not cut-off. We usually want at least a cm between the text and the edge of a page.

Ideally we could have considered the margins before we started making the document. If we have not there are a couple of options available to us.

- We could modify the document so that there is at least 3mm of margin (or content that will not be printed)

- We can simply scale the document when we print it

If we are using option 1 above then the exact approach will depend on the software used to edit the document. If we are using option 2 then the approach will depend on the software used to print the images.

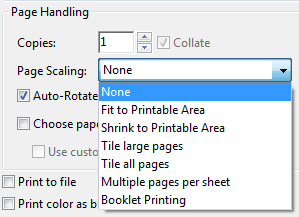

Printing and scaling

Printing can be kind of confusing because of the variation and duplication of options between the software used to print, the printer drivers and potentially the printer itself.

There is usually an option in the software used to print that allows you to scale the page to fit the printable area (paper – printer margins). If you are printing to A4 and your printer needs 3mm of margin then the printable area will be 297mm-3mm= 294mm by 210-3mm=207mm, which equates to scaling by 97%.

Margins for large format printing on the geology plotter

For a breakdown on printing on the geology plotter (large format printer for posters maps etc.) please look at this poster: printing_on_the_plotter

TIP: A good trick with printing is to print a document to a pdf first to check if there are any issues with printing. Be aware that saving to a pdf in word reduces qualtiy of graphics, it is best to print to a pdf. Most professional printers prefer printing from pdf format (including otago uniprint) for text documents (e.g. theses).

Pixel count, pixel density, document size, dots per inch, optical resolution

There are a lot of articles out there on the web that discuss these topics. Although understanding these concepts is inherently a little tricky, the biggest problem is the lack of consistent and unambiguous naming. In this post I will describe what these things are as unambiguously as possible. I find that sometimes its easiest to describe what you mean rather than using these names.

Definitions

Pixel count (aka pixel dimensions, resolution)

The number of pixels in an image may be reported as

- a width * height e.g. 1024*768pixels

- a total number of pixels e.g. for cameras: 2450*3700 = 9065000 Pixels = ~9 Megapixels

Pixel density (aka: digital resolution, resolution)

Often incorrectly referred to as dots per inch (see description for DPI below)

A measure of the density of the pixels in physical space. For example how many pixels in one linear inch (PPI).

This may be reported for screens; for example a 1920*1080 monitor that is 26.7inches across will have a pixel density (resolution) of 1920/26.7 = 72ppi. Note that most monitors with this pixel count are smaller (maybe 23inches) and thus have a pixel density (resolution) higher than 72ppi.

Raster images (e.g. photos) also have a value stored for pixel density (resolution). By default most cameras will set this value to 72ppi.

If you are scanning something than you may choose a resolution for scanning such as 300ppi for documents and 1000ppi for slides. In this case it is most likely that the value stored in the file will be this value.

Document size (aka: image size, presented size)

Not to be confused with image file size (aka: image size) which is the size of the image file i.e. 2.5MB.

Document size is the physical dimensions that an image has (perhaps measured in cm or mm). This is easier to get your head around for printed material where we can just get out a ruler to measure the image size.

For raster images (e.g. photos) on a computer the document size is actually just whatever is calculated using the pixel count and the pixel density.

pixel density = pixel count (in one direction)/ image size (in one direction)

For example if an image is 2400pixels across and has a pixel density of 300ppi than the document size will be 2400/300 = 8 inches = 203.2mm, that’s slightly less than the width of an A4 page.

Dots per inch (aka: printed resolution, dot density)

Printers have limited colours (usually just cyan, magenta, yellow and black). In order to create all the colours and tones for a photo these colours are printed in variable amounts as a dot pattern. If you look closely at a printed page or use a magnifying glass you can see this dot pattern.

The higher the number of dots per inch there is in a printed image the greater the level of detail typically. More dots are required than the pixel count to get the same detail as an image on a screen. Printers will typically print at 300dpi, 720dpi or higher.

Dots per inch is commonly used interchangeably with pixels per inch. This is wrong. Pixels per inch is the correct term for pixel density on a computer and dots per inch is the correct term for printed images.

Optical resolution

Optical resolution is a measure of the ability to resolve detail in an image. A simple way to measure this is to imagine the smallest and closest possible objects that can be resolved as two distinct objects.

This is perhaps the least considered aspect of images and image capture (e.g. photography, scanning) and one of the most important. Optical resolution, is perhaps the only true resolution.

While the pixel count sets an upper limit for optical resolution it is generally the optics of the image capture system and in the case of photography the quality of the camera and skill of the photographer that determine the optical resolution.

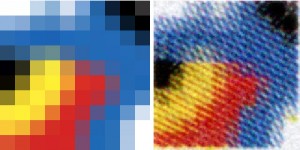

To understand how pixel count is different to optical resolution let us consider two examples:

- If an image is out of focus then it will have a lower optical resolution than an image in focus that is captured using the same pixel density.

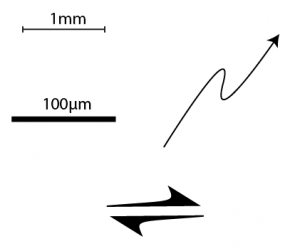

- A slide scanner can capture at 1200ppi, 2400ppi or 4800ppi, however due to the optical resolution limit of the scanner there may be no difference in optical resolution at 4800ppi vs 2400ppi. At 1200ppi the optical resolution of the image captured is lower than at 2400ppi because the pixel density is now the determining factor. See image below.

Keeping a symbols document

Why and how?

Sometimes we use the same symbols over and over in different documents. It might be easiest with some of these symbols to store them in a ‘symbols’ document. You should use the native format for whatever software you are using, i.e. if using illustrator use an .ai file. You could store this symbols document on the desktop.

Why use this approach?

Most software has more sophisticated ways to store symbols, the downside to these are that they are a little complicated. This approach is super simple.