Reach for the stars that burn brightest in your universe !

Wishing our 2017 Cohort every success in the future

Look forward to seeing some of you here at Otago University next year!

Te Kohanga Pūtaiao

Monday, December 4th, 2017 | STEPHEN BRONI | No Comments

Friday, October 27th, 2017 | STEPHEN BRONI | No Comments

I came across this short TED talk the other day and found it intriguing in its application of maths and geo-positioning physics. Not to mention the claims for its implications to future global society.

A precise three-word address for everyplace on earth

But just what really are the pros and cons of this system?

Get your critical thinking cap on and let us know your thoughts.

You might also want to check out what YOUR 3-word address is here.

Tuesday, May 30th, 2017 | EMILY HALL | No Comments

For this week’s blog, I thought I would look at an area that many OUASSA 2017 teams seem to be struggling with, breaking up the work for the team presentation. I have put myself into the roll of the team leader. I wrote up the presentation outline (which I did alone but really the team leader should be doing this with input from their group) and then I thought about how I would break up the work of the presentation to a hypothetical group of 6 team members. I picked 6 because that 7-9 is the group size for our OUASSA 2017 students.It didn’t actually take me very long to think about the outline and write it out. The most important thing to remember at this stage is that it is a work in progress. As we research and craft the presentation, some of the things I have written on my outline may change, and that is ok. It is a guide to myself and my team for where we are generally heading with our presentation. Having a good outline will ensure that my team is on task and not wasting time on research we won’t be using for our presentation. It also helps everyone in my group have a clear idea of what the big picture will look like, and where their piece fits in.

For this week’s blog, I thought I would look at an area that many OUASSA 2017 teams seem to be struggling with, breaking up the work for the team presentation. I have put myself into the roll of the team leader. I wrote up the presentation outline (which I did alone but really the team leader should be doing this with input from their group) and then I thought about how I would break up the work of the presentation to a hypothetical group of 6 team members. I picked 6 because that 7-9 is the group size for our OUASSA 2017 students.It didn’t actually take me very long to think about the outline and write it out. The most important thing to remember at this stage is that it is a work in progress. As we research and craft the presentation, some of the things I have written on my outline may change, and that is ok. It is a guide to myself and my team for where we are generally heading with our presentation. Having a good outline will ensure that my team is on task and not wasting time on research we won’t be using for our presentation. It also helps everyone in my group have a clear idea of what the big picture will look like, and where their piece fits in.

So on to the mechanics of it. I wrote what I was thinking each step so hopefully my handwriting is legible to all

The final step was filling in the rest of the form. I thought about what I needed people to understand to convey my message. I need people to understand what is fission, fusion and the difference between them. I have a really broad idea of how I want the introduction and conclusion to look but it’s not finished yet. For a first draft, this is totally fine, we’ll come back and tweak this while developing the presentation.

Finally, how will my group divide the labour so that we do the work that needs to be done but don’t waste time on anything else? This is what I came up with:

We will manage everyone’s ideas and contributions in a google doc that we can all contribute to. I know that some of my team are really busy with winter sports in June so they will do the research so that their part is finished early on. Those of us not as busy closer to camp will do the parts that depend on the research.

At camp we will rehearse our visualisations together and tweak our presentation before we show our presentation to the panel for feedback. This shouldn’t take long if everyone has done their part.

I have attached my full outline form: ScienceShowOutline.

Hopefully this will give you guys a bit more guidance on how to distribute the labour and what we expect you to be doing. Remember, we are only an email or phone call away if you need any help.

Friday, May 12th, 2017 | EMILY HALL | No Comments

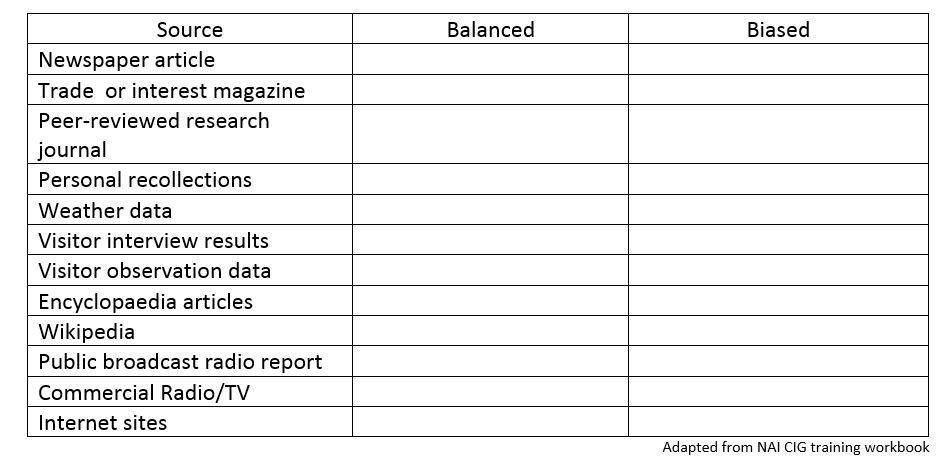

OUASSA 2017 students have been working towards a presentation to the public at the Otago Museum which will take place on July 14th. The research for their presentations are in full swing and things should be starting to come together for their presentations. Some recent experiences have reminded me of the importance not only of researching your topic, but of evaluating the information that you find.

Evaluating the information you find is especially important when researching topics that are emotional or controversial, where people are inclined to have opinions based on anecdotal evidence from the world around them. Many of the topics that are being researched for presentations in July fall into this category. People feel very strongly about topics like Climate Change, Genetic Modification and Medicine in the Third World. It is important in a presentation to the public that you are presenting the science behind the issue and relying on provable facts rather than popular (or unpopular) opinion.

The internet is a great place for research because you can very quickly find a lot of information. The downside though is that unlike a book or a research publication, anyone can put information on the internet without any verification that it is actually true, and present it as fact.

For that reason, it is very important when you are researching to make sure that you evaluate the sources that you are using. Although after researching, you may have formed a personal opinion on the issue, it is important that when researching, you are looking at unbiased information based on fact (or at least that you are conscious of the bias and are looking at the information with that in mind).

The library have produced a nice little reference for evaluating internet sources using the acronym BAD URL. You can find a copy here. How_to_Evaluate_Websites

If you want to really dig deeply into how to evaluate sources, this is an e-learning module produced by the University library designed to help you learn about different types of information sources and how to evaluate them.

In July, the students will be having a presentation on “What your brain does when you’re not looking.” Unconsciously, we all are influenced by our bias and frame the world through our own experiences. It is important to make sure we are aware of this and do as much as possible to limit bias in our work and promote impartiality.

Friday, April 21st, 2017 | STEPHEN BRONI | No Comments

In this week’s Science Communication post I thought I would focus on Introductions.

Your introduction establishes not only the topic your show is about but also who you are and the theme or key message you plan to deliver about that topic.

It’s your opportunity to let the audience know the nature of the journey you are going to take them on and engage them right from the start.

There are variety of ways to engage your audience in your introduction

I’m going to focus on just three today

The first is from a Royal Society lecture on antimatter by Tara Shears. Note the strong eye contact with the audience, the structured outline of what is to follow and the emphasis on the fact she will be explaining the relevance of what she will cover.

The second is by climate scientist James Hansen. Here he uses a strong question as an attention grabbing tool and goes on to introduce the science via anecdotes from his own personal journey.

This speaker relies heavily on reading his script. Do you find this style more or less engaging than that of Tara Spears? Imagine how much more engaging he would be if he were to abandon reading every single word of his script as written, step out and face the audience with strong eye contact as he relates his own personal story. He knows his own story. Does he really need a script for that? Would it not be that much stronger adopting a more conversational tone along the lines of what you would use when relating a story from your past to a friend or colleague?

The 3rd is Dr. Jenny Germano a dear colleague from my days as Volunteer co-ordinator at Department of Conservation. Jenny went on to study urinary frog hormones here at University of Otago. On the day she submitted her PhD thesis she entered the ` 3min Thesis’ speech competition with a talk entitled “Taking the Piss out of Endangered Frogs” …..and won the competition!

A number of things to note with Jen’s introduction. Her passion for her subject hits you from the word go, her use of hand gestures builds on that engaging passion and is even used to good effect in clarifying a couple of semi-technical terms- cardiac puncture and orbital sinus – simply by pointing to her heart and eye in mid-stream without having to pause. Note, no notes or script. She knows the stuff so she can talk from the heart and focus on the audience and not on trying to remember what comes next.

(Note that the graphic in the body of her talk is targeted at an audience of entirely academics as opposed to the general public audience you will be presenting to in July. So bear that in mind when composing your own graphic support material. The less technical the better for our audience in July)

Wednesday, April 12th, 2017 | EMILY HALL | No Comments

I was looking at some research into Science shows and came across some key findings on how to engage children from Science Museum (UK) focus group research undertaken in 2010:

• Audience participation is regarded as crucial – if children aren’t involved, they may lose interest.

• Parents like young, casually-dressed presenters, rather than the stereotypical white-coated ‘nerd’; they feel an informal approach is important in removing barriers to children’s appreciation of shows.

• The three words they felt would most attract their attention in descriptions of the show were Fun, Exciting and Interactive

For this week’s blog post, I tried to look for some novel ideas on how to present Science to an audience. Keeping in mind those ideas from the focus group on keeping it fun, exciting, and interactive.

One really amazing thing I found was Biology for the blind and partially sighted. Using 3D printing to bring the microscopic world to people who otherwise wouldn’t have any experience of it. Definitely worth watching, especially the audience reactions to being able to interact with the microscopic world for the first time in their lives!

For another novel presentation method, check out this TED talk about dancing scientific concepts which includes, among other cool things, a great example of the difference between ordinary light and lasers using dancers. The 2016 winners of the contest that he mentions “Dance your PhD” are also worth a look. I particularly liked the people’s choice award winner.

I have already shared with you what I think of as some good examples of story telling in Science Communication in a recent blog post on storytelling.

I also emailed the students some examples of one person’s use of music as Science Communication.

Videos are a very popular way to get the message across and the students had a tiny taste of this in the January camp Science Communication sessions. Videos don’t have to be hugely costly high technical productions to be effective, some of the best videos are really simple, for example, Minute Physics.

So hopefully that has given you a bit of inspiration to think outside the box for your presentations. Whether you present your information in the form of a song, a story, a video, a show, a play or something else, using a novel presentation method is one way to keep it fun, exciting and interactive.

Thursday, April 6th, 2017 | STEPHEN BRONI | No Comments

In my last blog post (Knowing Your Material) I talked about researching your topic and the importance of narrowing down that research to address a key message (theme) i.e. the `take-home’ message you want the audience to understand about your topic. When we understand something we don’t just `know’ about it but we ‘feel’ for it – it means something to our overall well-being. So in communicating science we need to not only enhance the knowledge of the audience but also engage their emotions, hence the reason your workbooks are entitled `Touching Hearts and Minds’. With that in mind, in this post I thought we’d focus again on the audience and what you might consider about them as you distil your research into an effective and engaging talk to deliver a strong ‘take-home’ message.

we understand something we don’t just `know’ about it but we ‘feel’ for it – it means something to our overall well-being. So in communicating science we need to not only enhance the knowledge of the audience but also engage their emotions, hence the reason your workbooks are entitled `Touching Hearts and Minds’. With that in mind, in this post I thought we’d focus again on the audience and what you might consider about them as you distil your research into an effective and engaging talk to deliver a strong ‘take-home’ message.

Considering your audience is especially important for a talk that involves science on a controversial or potentially controversial topic.

We should consider our audience for every talk, of course.

Questions you should consider when asked to give any talk are.

Will I be talking to:

• An interest group with a specific viewpoint/attitude to my topic and/or science in general?

• Is there likely to be a specific age or gender or ethnic imbalance in the audience?

• Is our audience likely to already be knowledgeable on my topic?

• How is the audience likely to perceive the organisation I am representing?

As Emily pointed out in an earlier post (The Crowd Goes Wild) a public audience will contain a mixture of what we could term:-

1. “Science Fans”,

2. “The Cautiously Keen”,

3. “The Risk Averse”,

4. “The Concerned”.

While your museum audience in July is likely to have a high proportion of “science Fans’” and “The Cautiously Keen”, you may also have parents/caregivers, members of public who fall firmly in “The Risk Averse” and “Concerned” categories. I think of these last two categories as people who come through the door thinking “this topic (science in general) is dangerous and poses a real threat to the health and safety of myself, my family, and or my existing way of life and things I currently value”.

With that in mind I came across an interview with Dr. Craig Cormick who has published widely on drivers of public attitudes towards new technologies.

The five key lessons that come out of his research on public perception of risk are as follows:

1. When information in complex people make decisions based on their values and beliefs rather than on facts and logic

2. People seek affirmation of their attitudes or beliefs, no matter how fringe, and will reject any information or facts that are counter to their attitudes or beliefs

3. Attitudes that were not formed by facts and logic will not be influenced by facts and logic

4. Public concern about the risks of contentious science and technologies are almost never about the science itself and therefore scientific information alone does very little to influence those concerns

5. People most trust the people whose values mirror their own.

What does that mean for us when preparing a science talk on a potentially contentious issue?

Good science communication is “more than information. It’s a revelation based upon information’”

In moulding how we present our information we are always seeking techniques that best acknowledge concerns, value systems within the audience and seek to lead them to that “Ah hah!” moment when they decide for themselves the positive values of the science you are talking about, rather than `being told’ by you the scientist/speaker. Once you have a base script for your talk we can look at which of the techniques we explored in our workshops and in our workbook might be most effective in making our presentation engaging, relevant and convincing. That’s one of creative, fun parts of pulling a good talk together.

Here is Craig Cormick’s interview:-

https://vimeo.com/umriskcenter/riskrage

It’s quite long, though the interview itself is only 27 mins there is 18 mins of Q&A that follows. If you get bogged down after the first 5 minutes of the interview here are some time cues to the more relevant and useful parts of his discussion:

9 min – Affirmation of fringe/whacko ideas and the Google search engine

18 min:32sec – The Role of Trust in influencing public perception

22 min:45sec -The Role of academics/researchers

26 min– Weirdest idea on the internet?

Perhaps the essence of what I’m trying to get across about science communication and contentious issues can be best conveyed in the following quote

“People don’t care what you know,

People want to know that you care”

Dr. Vincent Covello

Centre for Risk Communication

Monday, March 27th, 2017 | EMILY HALL | No Comments

“Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

—100 Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

—Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

“Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday; I can’t be sure.”

—The Stranger by Albert Camus

“The Man in Black fled across the desert, and the Gunslinger followed.”

—The Gunslinger by Stephen King

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into an enormous insect.”

—The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka

These are the first lines from some random, well known stories. You can find lists of best first lines or exciting first lines all over the internet. No matter what story they come from though, they all have one thing in common, the first line needs to set the scene but also leave you wanting more.

There’s no doubt that a good story has the power to hook us, reel us in, and capture our imagination until the tale is through. Everyone, young and old loves a great story. A good story can be a powerful vehicle to impart information.

Building on the idea from two weeks ago that to engage an audience, you need to:

Think about the stories that you have enjoyed, did they do these things? Did they validate your thinking? Take you on a journey? Were they framed within your values?

The point is – storytelling is a powerful tool. It may be the most powerful tool that you have to engage with your audience. When you are developing your presentation, think about the story behind it. Take the audience on a journey with you through the story you tell.

Here are a couple of examples for you to look at:

Example 1: Fergus McAuliffe speaking at the TEDX in Dublin tells a story about frogs. I particularly like this example because he has no slides, and only a few simple props, but at the end the audience is absolutely silent and spellbound.

Example 2: Tyler DeWitt speaking to high school science teachers. This one I chose because in contrast to the previous example, he uses visual aids behind him to tell the story. The story was part of a talk to teachers about the differences he found when presenting the material in a traditional way and using the story format (in the video clip) again, an engaging story that makes the science relatable to the audience.

Example 3: This is a LONG story but it is a good one. Jay O’Callaghan was commissioned to make a story as part of NASA’s 50th Anniversary. He tells a love story between two young NASA interns in modern times but interwoven is a lot of science and history of NASA. He tells it with no props, no visual aids, just a story. Engaging the audience with nothing more (or less) than a story.

Forged in the Stars – Jay O’Callaghan

Thursday, March 23rd, 2017 | STEPHEN BRONI | No Comments

No-one expects you to be an expert on your topic and there is only so much you can cover in a 10 minute presentation. However, you should research your topic thoroughly. A good research plan will help ensure accuracy, establish credibility and achieve your objective of enhancing understanding. When you have decided on the key areas of your topic you want to focus on divide up the research duties amongst your team.

Your key research areas will come out of Step 2 of your Topic to Theme Recipe.

i.e.

Step 1. Select a general topic

“Generally my presentation is about………………

Step 2. State your topic in more specific terms

“Specifically, however, I want to tell my audience about………………”

Step 3. Now, express your theme.

“After my presentation, I want my audience to understand that……………”

Remember to complete each line as one complete sentence. This will help focus your research on the key aspects of your topic that are relevant.

(From Sam H. Ham, 1992)

Beware of Bias!

Good research materials should be objective, presenting a balanced view of the topic. If you deliver biased information, your credibility with the audience will suffer.

As you embark on your research take a minute to reflect on the following sources and their potential for bias.

You may find this link designed for first year Otago University students useful also

You may find this link designed for first year Otago University students useful also

Evaluating Information Sources: http://oil.otago.ac.nz/oil/module7.html

Credit Where Credit is Due

If you use someone else’s ideas, words or pictures in your presentation, you should acknowledge the original source if known. You can do this by:

Failure to give credit where credit is due may damage your own credibility and violate copyright law.

What’s Hot and What’s Not.

As you do your research, remember:

People love to hear:

(Adapted from `Neuroscience for kids’ by Eric H. Chudler)

They don’t really care much about….

Good luck with your research and remember we are here to help so don’t hesitate to get in touch if need clarification and/or help with anything.

Monday, March 13th, 2017 | EMILY HALL | No Comments

In July, our current OUASSA student cohort will present short public science shows at the Otago Museum. This is the third year of students to undertake a public show. At the moment, the students are working on their topics and themes (as per last week’s blog post). In developing these though, there has been some chat in their presentation groups online about the audience.

Who is the audience for a public science show? We’ve told the students that it can be anyone from adults to children, people with PhDs in the topic they are talking about (we are at a University after all!) but equally likely people who know nothing about the topic.

We can do a little better than these generalisations though if we look at who is most likely to attend these shows. The general public can be very broad, but it is likely that we will not have a true general public audience but rather a subset.

At the ASC Conference, one of the speakers gave an excellent talk about this very topic. From my notes on the talk, the general public can be roughly divided into 4 groups when it comes to Science Communication:

At another session, a speaker who was arranging events based on Astronomy found that the people who came to the astronomy outreach events were generally young, University educated adults. At the Otago Museum, where the student event will be held, we know that they get a lot of young families coming through the door, parents who fit into one of those first two categories bringing their children to hopefully pass on their love of science or sometimes, children who fit into one of those categories bringing along an open minded parent.

So what does this mean for the students who are working on their shows? I think the first thing to remember is that the people who come to the show will most likely be from those first two groups, they will either be science fans or cautiously keen. This means they will already be open to what the students will be presenting and interested. Interested enough to give up an afternoon and maybe even bring the family along. So we can reasonably count on a friendly audience.

They’ve come in the door friendly and interested. Now what? People in general are funny creatures. They tend to work on emotion and intuition rather than facts. Think about a teacher that you had that you really feel like you learned from. Did you like them? Relationships are very important in communicating a message. The audience has to trust you, trust that you have their best interests at heart and relate to you enough to want to hear what you have to say. That connection with the audience at a personal level is more important that being seen as an expert. Students are often worried that they don’t know enough depth in their topic to be on stage telling the public about it. Knowledge is definitely important, but I would argue that it is more important that they come across to the audience as trustworthy, relate-able and passionate.

More notes from the ASC conference: an engaging outreach activity will:

A 10 minute student public talk is not the time or place to be confronting, controversial, or push a view on a particular issue. The aim is to have the audience leave happy and hopefully having learned something. Very often when students begin their Science communication journey, they subscribe to a deficient model of thinking. The public doesn’t know about X and it is my job to make them understand and accept it. Instead, knowing that the audience is most likely already engaged in some way, with these talks, the focus should be on giving the public enough of a glimpse of the topic that they go away wanting more.

So hopefully that helps a wee bit with the preparation of the public shows. The audience doesn’t expect you to know everything, they expect you to show them something they don’t know or show it to them in a new way. Your enthusiasm and interest in the topic will go a long way to making the audience want to engage in your show and take that journey with you.

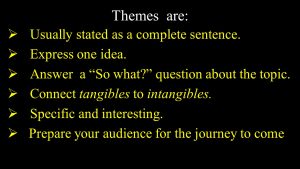

Tuesday, March 7th, 2017 | STEPHEN BRONI | No Comments

During our very short foray into some key techniques for engaging a public audience I emphasized the importance of moving beyond merely having a `topic’ for your talk and developing a ` theme’, or key message, that you want to convey about your topic in the 5-6 minutes that you will have for your science shows in July.

It’s great to see some of you moving in this direction in your closed Google Community groups. I strongly encourage you to use the three sentence approach to taking a topic to a theme developed by interpretation specialist Sam Ham. Namely:

Step 1. Select a general topic

“Generally my presentation is about……

Step 2. State your topic in more specific terms

“Specifically, however, I want to tell my audience about…”

Step 3. Now, express your theme.

“After my presentation, I want my audience to understand that…..”

Complete each line as one complete sentence.

This will not only give you presentation a focus it will make researching for your show that much more manageable.

A worked example

Grace posted this as part of the Medical Science group discussion

“What is antimicrobial resistance and how do we combat these new resistance mechanisms that are emerging and spreading on a global scale”

Step 1. Select a general topic

“Generally my presentation is about…… Antimicrobial Resistance

Step 2. State your topic in more specific terms

“Specifically, however, I want to tell my audience about…

..what antimicrobial resistance is, how it is emerging and spreading on a global scale, and how we might combat it”

Step 3. Now, express your theme.

“After my presentation, I want my audience to understand that……………..”

This, your overall theme for the show, will come out of the research you do to address the 3 sub-topics in Step 2 above

Sub-topic 1: What is Antimicrobial resistance?

Sub-topic 2a: How it is emerging.

2b: How it is spreading.

Sub-topic 3: How we might combat antimicrobial resistance?

A key message or sub-theme can then also be developed for each of the sub-topics above

e.g

The sub-theme or key message around sub-topic 1: What is Antimicrobial resistance? might be something like:

or

You then do the same with sub-topics 2 and 3 and come up with the key message you want to convey at that part of your talk. Out of which will come an over-all theme for your whole presentation which you can use to develop Step 3

“After my presentation, I want my audience to understand that……………..”

After you’ve done this and only after you’ve done this you can then distil a snappy theme title for your show.

It really is that simple, but like science itself you have to apply some rigour and consistency to the steps.

Give it a go and email me your first crack at ` 3 sentence theme development sentences’ by March 13th.

Don’t worry if Step 3 is not quite refined. Your final theme statement will emerge from the research on the body of your presentation (Step 2).

Look forward to reading your topics and themes.

Tuesday, February 28th, 2017 | EMILY HALL | No Comments

Last night I returned home to Dunedin from Adelaide. I was attending the 9th annual Australian Science Communicators conference where I had a presentation to give and also a poster in the gallery. The conference was amazing and I learned a lot which will be shared over the coming weeks.

On the weekend after the conference I stayed in Adelaide and visited a number of the city’s attractions. It may have been the conference leaving Science Communication in the forefront of my mind but I found myself analysing each one in terms of good communication and engagement. There is still a LOT of static displays and writing to explain displayed artefacts in museums. In one of the conference presentations, a panel tried to address this – but by far the most effective presentations were the ones that were interactive.

One very simple example of this was the crosswalk activity that I encountered at the Migration Museum. The exhibit was meant to show how immigration policies in the first half of the 1900s favoured a certain type of migrant (white and British). Instead of screeds of writing and examples or even just a small statement, there was a large crosswalk on the wall. You read a description of someone who wanted to come to Australia at the time and then pushed the crosswalk button. The walk man lit up if they could immigrate, the don’t walk sign lit up if they couldn’t and a yellow traffic light was a maybe. A small lit up explanation of why that particular person could or couldn’t migrate was also displayed.

I think this was a brilliant example of how a simple metaphor (the crosswalk) was used to make information very relevant. Everyone crosses the street, imagine not being able to cross the street because of your race or circumstances. It certainly made me think about immigration and the effect of policy on people at that time. The setup was also engaging. I probably would have walked past a panel of the same information if it had just been written up on the wall.

So over the coming weeks I’ll share more of what I learned in Adelaide but my learning for today is the power of the simple metaphor. Finding something your audience relates to and use it to convey your message.

Wednesday, February 15th, 2017 | EMILY HALL | No Comments

Recently, the company that I have been buying facewash from since I was 18 years old, ran out of the product I use. Rather than settle for something else, I did a wee bit of research online and found a recipe to try.

The whole experience reminded me of a unit that I ran with my Year 10 class a few years ago. We had finished a unit on Acids and Bases and so they were familiar with things like the pH scale and we had looked at cleaners, toothpaste and other common household items. I had run across the resource “Lips, Lipids and Locks” in the resource room and decided to make a mini unit around it.

Firstly, the students read the book. They then had a think in groups about what kind of products they used on a regular basis and what chemicals were in them. We did a small group and whole class brainstorm about the types of cosmetics they could reasonably make.

They then did some research about recipes, decided on a recipe to use and came up with a “shopping list” of ingredients. Once we had gone through the ingredients, there were things that we couldn’t get either because of cost or because it wasn’t available in a timely manner. This meant the students had to go back and look at alternatives.

Finally, we spent some time making and testing out their products. Once each group had a product, it was presentation day. The students presented their products to the class along with their ingredients, why their ingredients worked and also if they had to use alternatives, what alternatives they used and why they worked. They had to talk about why they had chosen one recipe over the others available. They also had to analyse their final product and talk about what they would do differently next time, what they liked/disliked.

There was not enough time for them to go through multiple production runs and refine the products which I think would have been a good learning exercise as well. I think this would have helped them understand what kind of research and development goes into creating the products they use.

All in all, I feel like they were engaged as they were making things that they thought were relevant. They also were developing their research skills and problem solving abilities. Finally they were communicating what they learnt to the wider group.

Back to my own experiment with facewash, with a small tweak it turns out I’m on to a winner. It was quick and easy and works well. If you’re interested in the recipe, here it is:

1/3 cup oat flour – oats have saponin giving them mild cleansing properties, they are also moisturising

2/3 cup almond meal – almond meal is used to exfoliate, it is high in B and E vitamins and it is also very moisturising

2 Tablespoons of honey – honey is an antimicrobial and also contains antioxidants

A few drops of melted cocoa butter – moisturising

Squish all ingredients together and store in an airtight container. To use, mix a pea size amount with water in hand and apply.

Recent Comments