The suffering of war, the eye of the beholder

A post written by Samuel McComb, for an ANTH424 assignment on ‘visual images and the communication of suffering and evil’.

“What has been seen cannot be unseen, what is has been learned cannot be unknown.”

– C.A Woolf

I love art. Creation in different forms has provided me with an outlet where nothing else can, and exposed me to works that have not left me to this day. Some I have carried lightly, while others remain as haunting as the first time I laid eyes on them.

One particular image has remained with me in a way others have not. It sits clearly in my mind’s eye. Without demanding focus or derailing the bustle of other thoughts, it simply reminds me of its presence with a whisper – “I’m still here”. For years I have held space for it, maintaining an uneasy truce. Decontextualized, it could do no harm nor be put to rest. But upon its most recent resurgence I felt compelled to understand more. I could not have predicted how thoroughly this discovery would challenge my perception.

Witnessing

My familiarity with this image harks back to my high school years. I was around 16, or perhaps 17, and in the midst of what one might describe as a period of healthy teenage angst, channelled and encouraged by an art department with an affinity for the grunge aesthetic. A plastic skeleton lived in the corner of the art room. The gift of a perfectly mummified cat (found when a neighbour’s house was relocated) received promises of “Excellence” grades for the year’s NCEA assessments. One lunchtime, two friends and I made the plastic skeleton a cardboard house, in the middle of the classroom. It was in this environment that our subject matter would be deconstructed, remade and distorted as we explored our theme; War.

Paul Frosh (2016), a media and communications researcher with the Department of Communication and Journalism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, made a strong argument that our ability to respond morally when witnessing suffering is shaped by how we view it – the medium used in its portrayal changes how we engage our senses. His conclusions are drawn from an analysis of user experience with Graphical User Interfaces (GUI’s) of smartphones and computers when viewing Holocaust survivor testimonies . These provided clear examples of how the experiences and actions we take when witnessing suffering shape our response.

Frosh then considered the moral obligations of the viewer when witnessing and responding to suffering. He divided these responses into three types: attention, engagement, and action. This was a useful framework within which view my own interactions with, and responses to, suffering, and specifically to explore how this raw image (fig.1) became the work I presented in my high school art folio (fig.3).

Attention

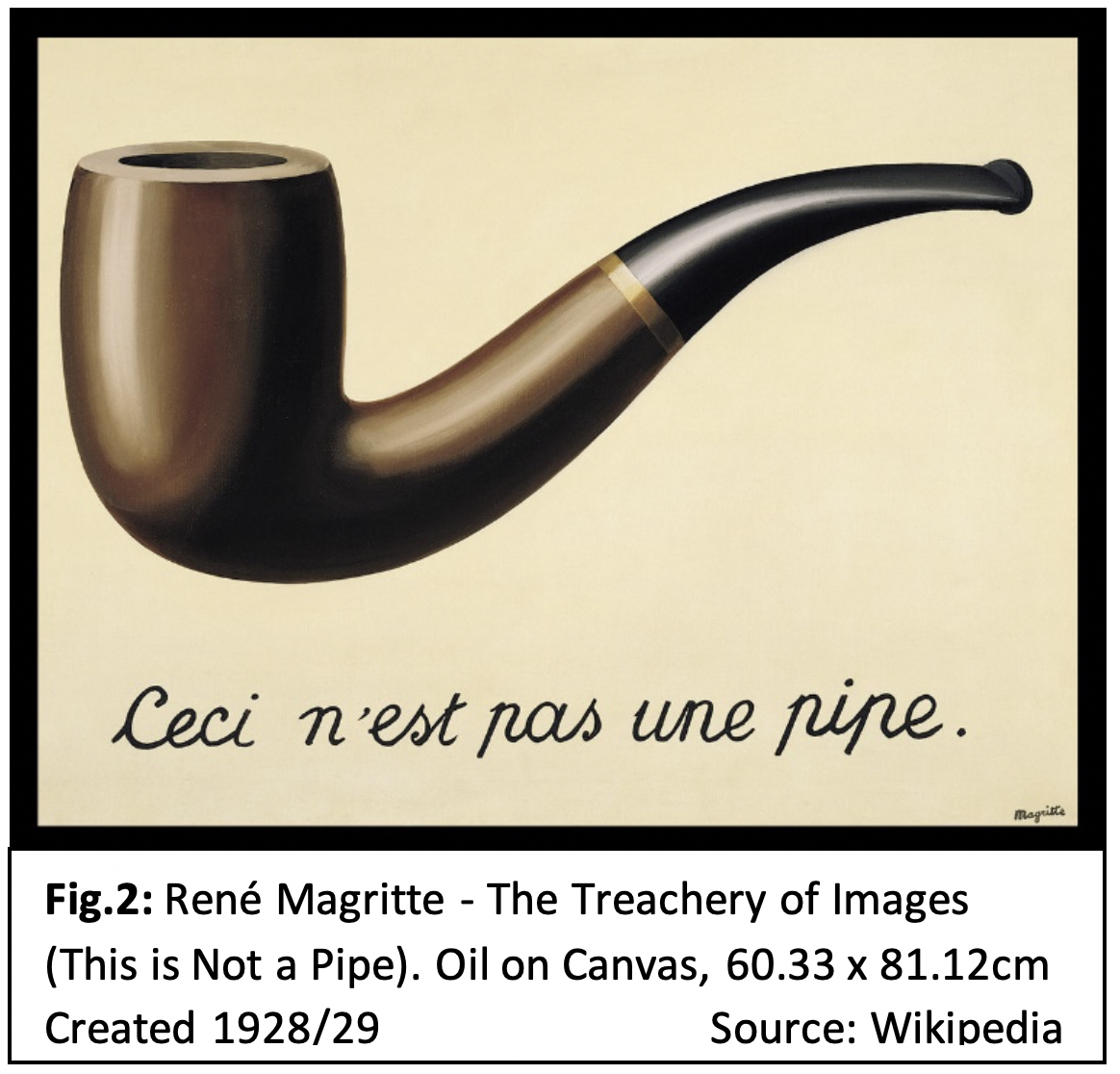

René Magritte famously captioned his pipe painting ’This is Not a Pipe’ (Fig.2); in other words, an image is not the object it represents. This is an influential idea in semiotics and fundamental to art.

René Magritte famously captioned his pipe painting ’This is Not a Pipe’ (Fig.2); in other words, an image is not the object it represents. This is an influential idea in semiotics and fundamental to art.

As I began my project, I was searching for images and shapes that represented an idea or a feeling. I first saw the soldier while shuffling through a stack of photocopies collected from old books and internet searches. These photos of medals, memorials, soldiers and statues had been carefully selected by the teacher to help us explore our theme. I recall that several images had been ripped by other students fighting for the ‘cool’ pictures – the ones with the biggest guns – by the time I began my search.

On one level these were just raw materials, no different to any other aesthetic resource provided by the teacher. Yet just as Frosh (2016) argued that how we access depictions of suffering plays a major role in our responses, the way I was searching for images shaped my response. I was holding history between my fingers, taking just enough time to gain some perspective of the content as I shuffled through the photocopies, before passing the stack of unsuitable pictures to the boy beside me. I could almost forget the reality behind the paper as I traced shapes overtop of figures, the smooth monotony of the paper interrupted by creases and rips as I thought of textures and colours to represent what I felt each copy contained. After the preliminary search, every raw image was subject to a deeper focus – I wanted to know what aspect of each photo captured my attention.

Action

Once we have seen suffering we are faced with a moral decision in how we respond. I could choose to ignore what I saw and felt in the image of this young soldier. I could choose another image, another topic to explore – my resulting artwork would have been displayed in the same way, to the same audience, regardless of the content. I could have found more images of big guns, but I didn’t. I needed to share what I had seen and felt.

Frosh (2016) describes the primary response to suffering in the digital age as communicative action – sharing a video or photograph widely, to raise awareness and prevent further actions, or simply to acknowledge that the suffering occurred. Sitting in my classroom, I needed to share what I had felt when I saw my soldier – the destruction of innocence that does not choose a side, the shared suffering inflicted on humanity through war. In this case though, sharing was not the quick click of a digital button, but a belaboured process of interpretation and creation with paint.

Sometimes we can choose to filter or curate our media feed, hide from the suffering before it overwhelms us. As in social media, so too in art we can choose to cover what we don’t want to see and focus on brighter times. Indeed Frosh (2016) makes clear there is the potential, when communicating enormously tragic events, for individual stories to be lost and the narrative of suffering to become overwhelming; the viewer becoming helpless and unable to respond morally to all they are exposed to. Reflecting on my folio (fig.3) certainly could elicit this response, I have to now reflect, as the young soldier becomes one small feature within the whole composition, one piece of a larger picture.

For a moment the viewer too feels the overwhelming weight of suffering that exists behind the barrier of our screens, and we become like my soldier, or perhaps the photographer – left with nothing but the ability to witness and remember.

Revelation

I never tried to find out more about the photographs I used at the time, nor in the ten years since I made this board. I knew the wars they came from, perhaps who they fought for, but not the stories of the men. In hindsight I was hiding from the full truth, keeping the distance of ignorance to keep from being overwhelmed. The folio received an Excellence, and placed second in my school that year, yet I have been almost ashamed to share it knowing so little about the history of my source materials. The most recent time my soldier whispered, I listened, intending at last to let him rest.

To my surprise it turns out the soldier who inspired my art, who has stayed with me for so long, was a work of fiction – filmmaker Berhnhard Wicki’s own moral response to suffering. My soldier’s photo was in fact a still from his film “Die Brücke”. Released in 1959, this West German film follows a group of seven 16 year old school students enlisting late in 1945. The film shows their experiences as they are sent to defend a bridge in their home town with almost no training, and all but one of the boys die as they experience the horrible reality of war. The film ends noting that it was based on a true story (IMDB, 2020).

Several things suddenly made sense when I found this out. Firstly, the affinity I had felt was real because the soldier was my age. Secondly, everything had been designed to elicit an emotional response from the viewer – camera angle, posture, positioning. I wondered if it was a sense of difference that made my soldier’s photo stand out among the stack – subconscious awareness that it was somehow wrong, or staged. But I soon realised that did not matter.

The intent of Die Brücke was to share an emotional response to the horror of war. More than fifty years on it continues to do so with just one frame. In doing so it continues to offer me a choice of moral action – turn away from the suffering, or witness it, and share a moral response of my own. The eye of the artist may say “This is Not a Soldier”, but through the eye of the beholder we can still say “This is Suffering”.

Sources:

Frosh, P. (2016). The mouse, the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response. New Media & Society, 20(1), 351–368.

The Bridge. (1959, October 22). Retrieved April 10, 2020, from https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0052654/

Fig.1 Source: Teeuwisse, J. H. (2017, March 3). NOT a photo of German child soldiers at the end of WW2. Retrieved April 2020, from https://www.flickr.com/photos/hab3045/33231024585/in/photostream/

Fig.2 Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Treachery_of_Images Retrieved April 2020

Fig.3 & Fig.4: My own work, photographed April 2020

The Smell of Suffering: Portrait of a Street Boy

Written by Yi Li, for an assignment on ‘communicating, consuming, and commodifying evil and suffering’, in ANTH424

Street photographers visualise social suffering through their artwork. They engage (themselves and us) with unfamiliar experiences: shrinking cities, strange portraits. Photographers can function as both moralists and anthropologists. They are often spectators, often self-exiles – presenting a version of evil for others to interpret, but often also fulfilling their own sense of moral obligation.

My argument is that both the positionality of the street photographer, and the medium of the photograph, means that photos sometimes break free from the time and space, conveying a universalism of personal adversity. I use an example of street photography of homeless in Moscow to discuss this.

Down and Out

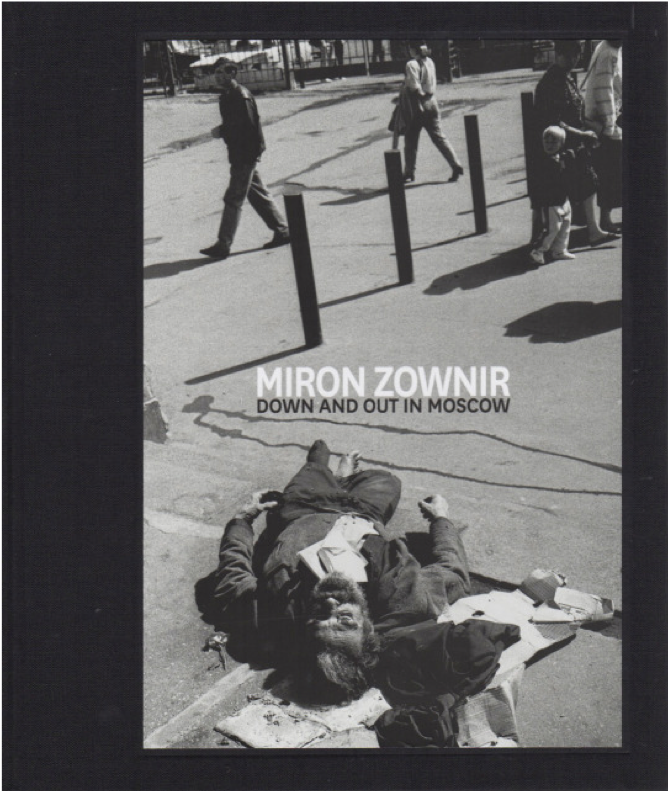

German photographer Miron Zownir is one of the most radical contemporary examples. His focus on marginal characters and the dark side of cities is rooted in his childhood. A Ukrainian-German who grew up in post-war Germany, Zownir as a teenager immersed himself in Eastern European literature without trusting any existing political systems or social stereotypes. His inherent interest in individualists inspired him to live in slum-like places, capturing streets with an anti-establishment attitude.

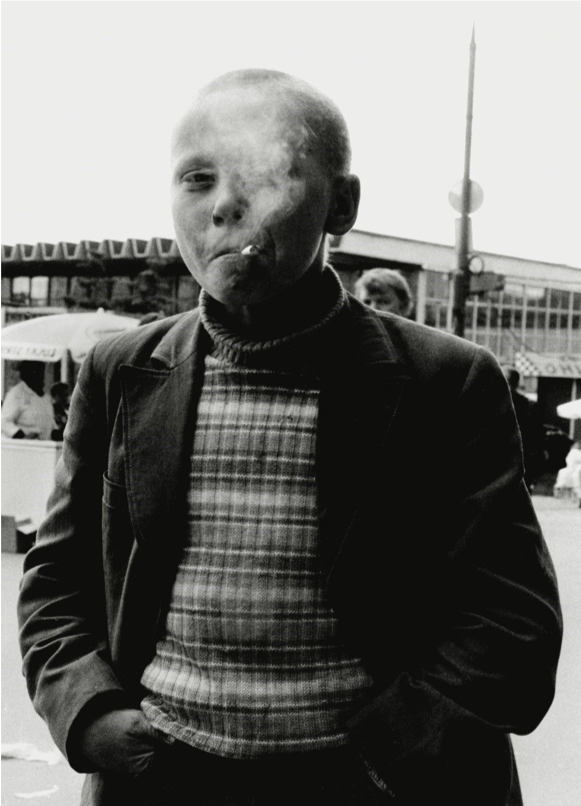

The street portrait is from Miron Zownir’s publication Down and Out in Moscow, a series of images that captured the homeless crisis in the Russian capital in 1995, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

I noticed the smoking boy with an adult expression to his cynical appearance when I first came across it in 2018. It is somehow different from the other challenging photos in his book. Momentarily, the encounter between Miron Zownir and the boy constructed a story about how individuals were abandoned by society. The diffusing cigarette smoke in front of the boy seems to allow me to smell the evil that permeated the city.

Kleinman & Kleinman (1996)[i] discuss the moral implications of photographs, through contextualising engagements within creators, audiences and images.

Zownir’s photographic experience runs through the technical transition: turning from black-and-white film to digital photography in the post-modern era. This photo was captured in a classic form, of black and white portraiture displayed in gallery spaces, and print journalism (books, and magazines). But it is worth noting that the extended agency of photographs can shift, depending on medium, from a momentary, regional realm to a worldwide standing discussion, through different forms of reprinting and representing.

How different would the viewers experience of this boy’s suffering be, scrolling past a small version in a social media feed? Touching his face on a tablet?

Moral Obligation in Street Photography: Unperceived Suffering as Social Experience

Anthropologists may ask: what is the basis of a photographer’s sense of moral obligation to take photos on streets?

Street photography concentrates on people and their behaviour in public, thereby also recording personal history: though without formal consent, and with the combination of spontaneity, outsider perspective, and private exploration. These subjects of circumstances are generally unaware – either stared at or ignored until they were documented. Street photography uses these collected narratives to define cultures or places, with no duty to serve a larger whole, and no limitation on how they reconstruct these places[ii].

Kleinman & Kleinman considered that photographers represent individual suffering as part of social experience, for others to access – whether these are extreme or ordinary forms of suffering. But as anthropologists, they caution that “there is no timeless or spaceless universal shape to suffering,” (1996, p:2).

In Down and Out in Moscow, Miron Zownir photographed death, sin, and a harsh lived reality. Underlying the powerless state, the rampantly violent proliferation pushed Moscow to become a hotbed of criminal forces in the 1990s; “the most aggressive and dangerous city, … people were dying right there on the street”.[iii] Such tension immediately changed Zownir’s original mission: to document Moscow’s nightlife with three-month project funding from a photographic committee.

Suffering is one of the existential grounds of human experience, and Kleinman & Kleinman suggest that moral witnessing also must involve a sensitivity to others, albeit with unspoken moral and political assumptions. Still functioning as a photographer, Zownir did not tend to query the government, or alter Moscow residents’ condition – but instead chose to live briefly in this shadowed twilight zone, to experience the nightmare.

Individual into the Universal: Reflexive Appreciation against the Silent Oblivion

How can we perceive a stranger’s suffering as universal? Here, a street boy’s sophisticated body language is beyond verbal expressions: dressing in a suit over a horizontal striped turtleneck sweater, his hands are hidden in his pants pockets like a social youth. He looks indifferent to the surroundings and unmoved by the photographer. He is clothed, unlike many beggars, and yet he was banished to a community where no-one had a home.

This portrait reminded me of the 1994 film In the Heat of the Sun. The film is based on Chinese writer Wang Shuo’s novel Wild Beast, which is set in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution, and tells how a teenage boy and his friends are free to roam the streets day and night in a period in which all the social and educational systems are extremely non-functional. Both protagonists are undergoing suffering – the film an example of the way their individual experiences can be abstracted and universalised, for the consumption of a wide variety of audiences. Yet this this also shows us how images and films can provide an insight into personal suffering that is usually invisible – although the harsh realities behind the lives they represent often go on unchanged.

The unwitting suffering of Zownir’s street boy is entangled with the political unrest in Moscow. But as a photograph, it also exists apart from the historical context: “a professional transformation of social life […] a constructed form that ironically naturalised experience.”[iv]

The frame itself cannot communicate this context. Yet it can communicate something else – the universality of human feeling event amidst diverse and ethically incommensurable [v] societies. Perhaps this is the power of portraiture – indeed the seminal psychological research of Ekman, and others, has asserted that emotional expression on faces is universal [vi] – meaning that moods and feelings may at times transcend cultural limitations, an idea often grappled with in the anthropology of emotion.

Conclusion: photography as a container of truth and imagination

Miron Zownir wrote in his poetry: When the earth returns with a thousand sunsets, the truth of the universal is darkness.[vii]

Photography blurs social facts, but seals emotions. Whether the boy would recognise the chaos, ignorance and madness that Zownir’s book communicates, in his free childhood in post-collapse Moscow, cannot be known. Yet seeing this photo as a cultural artefact, we can recognise that both the photographer and the audience as complicit in reproducing and politicising fragmented histories in photography. The photograph becomes a container for these forms of imagination.

Several years later after this photo was taken, when Miron Zownir was back in Moscow for his upcoming exhibition, the city’s exterior had been cleaned up. The silent responses of audiences standing in front of an enlarged version of this photograph, seemed at a vast remove from its original context. What meaning, what comfort, did it hold then? Yet the world still calls for images, as ‘the mixture of moral failures and global commerce is here to stay’ (Kleinman & Kleinman 1996: p. 7).

References:

[i] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[ii] Levy, S. (2019) ‘Street photography as a process’ in Lens Culture Guide to Street Photography, pp. 8-12

[iii] Zownir, M. (2014) ‘I was always an individualist’, Berlin Interviews, by Katerina, http://berlininterviews.com/?p=1375.

[iv] Kleinman, A. & Kleinman, J. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

[v] Fassin, D. (2009) ‘Beyond good and evil?: Questioning the anthropological discomfort with morals.’, Anthropological Theory. Sage, 8(4), pp. 333–344.

[vi] Ekman P, Friesen W (1976). Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press : Palo Alto.

[vii] Zownir, M. (2018) ‘Black’, Vision

Vaccination debates and the pain of dividuality

**Post originally published on Corpus: conversations about medicine and life, August 7, 2017; with thanks to Sue Wootton for editing and for permission to republish**

Dividuality: “the close proximity and unexpected pull of others in one’s life” (Garish Daswani 2011).

My ears are full of screaming: the name-calling, the CAPS, the exclamation points!!! Whenever vaccination comes up online, and comments are enabled, the conversation quickly devolves into an extremity of outrage and vitriol that reads to me like ‘moral panic.’

My ears are full of screaming: the name-calling, the CAPS, the exclamation points!!! Whenever vaccination comes up online, and comments are enabled, the conversation quickly devolves into an extremity of outrage and vitriol that reads to me like ‘moral panic.’

Coined in the late 1960s, the term ‘moral panic’ makes no judgement on the value of the issues under discussion. Rather, it highlights the social processes in the associated public discourse: the way that story, meaning, and affect coalesce around a particular social problem. Untangling an objective sense of risk from this is nigh on impossible. Besides, people are doing stupid, risky, and harmful things to each other, directly and indirectly, all day long, and in every part of the world. The question becomes not what to think of anti-vaxers, but why the panic about this particular issue, why here, and why now? I believe the answer is not purely medical, but also social and moral.

In matters of morality the contemporary Western world cries ‘choice’ until the word is nearly meaningless. Liberalism snuggles up next to secularism. We fiercely defend our (and others’) rights to make personal decisions, based on personal beliefs. What the issue of vaccination makes horribly clear is the reality is that you can make your personal decisions, based on your personal beliefs, and they can still kill my child. There are limits to our liberalism. Is this the sore spot that the vaccination debate is poking its sordid fingers at? That the personal is social, always.

Arthur Kleinman – psychiatrist, clinician, social anthropologist – discusses morality by looking at “what matters most” or “what is at stake”. In matters of health this includes relationships, personal values and identity. What produces such heat in the debate about vaccine-preventable diseases is that it’s not only individual biographical identities that are threatened, but deeper cultural constructions of the ‘self.’ What the debate specifically grates on is our sense of ourselves as individuals: our clung-to Western vision of the autonomous, bounded, individual self. Silos. Self-governed islands.

Arthur Kleinman – psychiatrist, clinician, social anthropologist – discusses morality by looking at “what matters most” or “what is at stake”. In matters of health this includes relationships, personal values and identity. What produces such heat in the debate about vaccine-preventable diseases is that it’s not only individual biographical identities that are threatened, but deeper cultural constructions of the ‘self.’ What the debate specifically grates on is our sense of ourselves as individuals: our clung-to Western vision of the autonomous, bounded, individual self. Silos. Self-governed islands.

Social anthropologists have compared the different notions of selfhood and personhood that emerge in diverse cultural settings. In many African communities, for example, ethnographic data paints a picture of the self as partible (capable of being divided), and porous (to both physical and spiritual substances) – not ‘individual’, but (according to ethnographers like Girish Daswani) ‘dividual’. This is quite a contrast to the ‘buffered self’ that is a feature of the Western secular age, where the ideal of healthy interpersonal relationships involves having strong interpersonal boundaries.

The vaccination debate invokes a sense of contamination and threat from other human beings. But bodies are never just bodies. They are the site of densely-packed social meanings, and the inspiration for the most accessible and powerful metaphors for pressing existential concerns. Thus the vaccination debate is not only expressive of anxieties about our biological health, but also about our social existence. As each image of an ailing child looms large on our screens, how outrageous it seems to have to acknowledge ourselves as herd animals in this way – how sickening and scary that what matters most to us is at the mercy of those around us. How intolerable. How basically, inescapably, human.

Dividuality cannot just be the folk theory of some cultures… it is the basic reality of all communities. There is an Irish proverb I have always liked:

“In the shadow of each other we must build our lives.”

Though bleak, to me its comfort is in the embrace of that inevitable entanglement with other selves. You will shadow me, just as I will shadow me. I can no sooner extract my life from the influence of others’ dreams, decisions, and faults than I can remove myself from the biological systems of immunity and disease. A relinquishing of the singular pronoun is needed: I, we, are in so many ways collective.

Robyn Maree Pickens’ beautiful essay on bees (published in Turbine/Kapohau 2016) evokes something of this; the sense of ecological interconnectedness which must be cultivated against alarm bells. She concludes by beseeching us to attend to the “nested lives of others.”

Robyn Maree Pickens’ beautiful essay on bees (published in Turbine/Kapohau 2016) evokes something of this; the sense of ecological interconnectedness which must be cultivated against alarm bells. She concludes by beseeching us to attend to the “nested lives of others.”

The air of panic that hovers over the vaccination debate reflects the existential nature of the concerns being expressed: concerns over the threat of vaccine-preventable diseases to the physical wellbeing of our children; threats also to our clung-to visions of ourselves as bounded individuals. We struggle in the grip of an impossible longing for both freedom to make our decisions and freedom from the effects of others’ decisions. Yet this is the shadow-dance we live in. Confronted with a perfect biological metonym for this crumbling dream of moral autonomy, it seems we can do nothing but scream.

Written by: Dr. Susan Wardell

References:

- Cohen, S. (2002). Folk devils and moral panics.

- Daswani, Girish. “(In-)Dividual Pentecostals in Ghana.” Journal of Religion in Africa41, no. 3 (2011): 256–79.

- Kleinman, Arthur. “Caregiving as Moral Experience.” The Lancet 380, no. 9853 (November 9, 2012): 1550–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61870-4.

- Pickens, R. M. (2016). We ask so much of them

Night terrors: Counting loss in a global pandemic

Posted on by smisu13p

A post written by Ellan Baker and Susan Wardell, based on an ANTH424 assignment on ‘visual images and the communication of suffering and evil’.

On March 19th 2020, social media and news sites were flooded with images of military trucks, moving the dead out of the overwhelmed small Italian city of Bergamo, for cremation elsewhere [i]. Europe had replaced China as a new epicentre of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The city of Bergamo. Source: pixabay.com

Northern Italy is known for having small towns and tightly-knit communities, as well as for the beautiful scenery, cuisine and fashion which attract both domestic and international tourists iv. It was largely through travel and social interaction, that the new strain of coronavirus (named SARS-CoV-2) was spreading. Places like Bergamo, a city of just over 100,000 residents, had little time to prepare iii ii.

Picturing the scale of loss

One of the images from mainstream television (Sky News) showing Italian army trucks transporting the dead. Source: https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-italian-army-called-in-to-carry-away-corpses-as-citys-crematorium-is-overwhelmed-11959994

At the time that images of the crematory trucks were released, Italy was in an exponential climb in the number of cases. The number of deaths had now become a few hundred a day, despite best efforts of intervention and prevention. On March 19th, total fatalities had reached 3,405 and were still increasing vi.

As the pandemic spread, people all over the world took in this type of numerical information, to make sense of what was happening v . Rates of spread, death tolls, graphs and spreadsheets… these were forms of knowledge about the reality of Covid-19, which were also somewhat removed from acknowledgements of the level of human suffering it was creating, with every new case, and with every death of a unique human person that those numbers represented.

In this blog we discuss the ideas that images, as a different way of communicating suffering and loss, can help to rehumanise topics such as this. We argue they provide understanding of the scale of devastation in a different way than numbers do, and can be part of catalysing social change because of this.

Echoes of (an invisible) war

Tightly packed, the military-style trucks are moving in single file down the street. The arrangement of the trucks on the empty street has a ceremonial feel; dark colours, and a string of lights. The road is clearly in an everyday residential area, with a shop, carpark and green field visible alongside. But here it becomes a platform for procession vii.

The escort occurred at night – the image taken at 9:28pm – almost as if they needed to hide the moving of the dead, and shelter the living population vii. Was the suffering so great, that it could not be experienced during the day? Like the living, the day is sheltered from agony; maintaining its symbolic goodness, while night is reserved for pain.

In the photo there are many trucks, and within each truck, there are many bodies vii. The photo both is and isn’t about numbers. The impact of this photo is largely because the trucks are in fact innumerable, their line extends out both sides of the frame of the photograph. It asks us to recognise the scale of loss without making us, or letting us, count and quantify. It evokes the horror of scale, without relying on numbers. It makes an affective connection to the topic, without being explicit.

The image of a fleet of military trucks can’t help but raise the ghosts of war; historical echoes that will have different levels of feeling attached for different viewers, in different places. At very least, the string of large trucks connotes a high number of casualties, and yet there is a disjunct for the viewer, since absent from the still and tidy environment they move through is any evidence of danger or threat. The toll is being counted, truck by truck, but the enemy itself is a ghostly absence; an invisible virus, impossible to see or to conceptualise, except through its effects.

Watching from afar

At this time this photo was taken and posted, New Zealand and many other countries felt far from the ‘front line’. The need to take action here was not yet evident. So we watched the situation unfold through images like this, but even as we did, the virus exponentially spread once again, leaving tremendous amounts of uncertainty in its wake iii

The now-famous images of these trucks did not come, in the first instance, from scientists, journalists, or other authoritative communicators. Rather they appeared in the often informal domain of social media. The context of apartments opposite implies that this photo too is taken from an apartment window, looking down. The photographer is distant from the street, giving an even more heightened sense of risk or taboo in the scene below.

The juxtaposition of the sombre with the everyday (both in terms of the setting, the intimate framing of the photo, and its context on social media) makes looking at it all the more difficult.

Images of tragedy and horror often circulate well on the media – like this one, going viral, reaching around the world. Anthropologists Arthur and Joan Kleinman wrote about the circulation of images in the media in 1996, before the advent of social media, and yet they discussed many trends we could see continuing, and even increasing, today. They note, for example “viewers become overwhelmed” from a distance and come to have “moral fatigue, exhaustion of empathy, and political despair.” ix

Given the continuous flow of numbers and statistics, of images and video, through the news, this could well have been the case. Yet people seemed to want to look. Kleinman & Kleinman also discuss that despite their potential to overwhelm, images of suffering are often appealing because they leave the viewer asking questions ix.

The unending line of crematory trucks going beyond the photo’s borders shows the impact of the viruses devastation. But what questions does it ask? Are they questions that are answerable? Either way, they were questions that New Zealand did have to approach, as citizens, and as a nation, not long after Italy.

The human struggle

“Struggling to cope” vii the photo caption says. This is, on one level, a comment about institutional and systemic capacity to practically process so many dead – since these trucks were deployed for the purpose of relieving an already overloaded crematory system vii. But the phrase can also read as a marker of psychological overwhelm for those living through the experience.

The pain that the virus has caused is immense. Images of the COVID 19 pandemic re-humanise numerical information, by bringing Twitter users closer to the suffering of those who are grieving losses of loved ones. This can be contrasted to the insistent numerical broadcasting, which removes the emotional quality and the human context of information, and by itself, refuses to acknowledge the human lives behind them. As the quote often attributed to Stalin goes: “if only one man dies … that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s only statistics.” x

Meanwhile, images have a variety of different ways of highlighting the specific, situated, and human meanings of these numbers. For example, the image below is of a blessing taking place by the service providers, to finalise the deceased person’s life, with dignity.

Photo of two men giving dignity to the dead, despite the large number of dead and the lack of family or friends of the loved one present. Source: Financial Times, https://www.ft.com/content/5e30a130-d62a-4c4c-a81f-b89f2448d9c8

This image, taken by Italian news photographer Piero Cruciatti, offers something different to the sense of scale of death and loss in Salvanechi’s image, in terms of communicating the impact of COVID-19. It reveals one part of the story behind each number, behind each body that the viewer understands to be concealed in those many military trucks. It shows the layers of human care and meaning invested into each of them; how the people closest to the suffering still muster the strength and urgency to undertake the enormous amount of cultural and physical work required to bring each person’s precious life to a close.

It shows, perhaps, the tragedy of the ‘one man’ rather than the thousands, and in doing so, it arguably brings a different kind of understanding of this event, than it does to contemplate the thousands.

Image and response

Paul Frosh, an academic writing about digital media, and specifically how people view and respond to the suffering of distant othersxi. One’s moral “response-ability”, he argues, is linked to the sensory mediums through which one is viewing and responding. People who viewing Salvanechi’s photo on Twitter, for example, had to choose how to respond, with their eyes, hands, and attention. Practically this could mean many things; clicking, commenting, sharing. More broadly, categories such as ‘witnessing’ explain what type of moral response these micro-actions may represent.

Images can broach both a geographical and emotional distance, and act as a testimony and a memorial in and of themselves, to human experience, and human suffering. In Salvanechi’s photo, and the photo by Piero Cruciatti, we are forced to consider the suffering that quickly can become incomprehensible and overwhelming vii– given a chance to hold our gaze, and to be witnesses to this horrible reality. And in doing so, to form a kind of momentary connection with other people’s life world’s that is void in the production of infographics and statistical data in journalism.

In addition, there are practical responses that can flow on from this deeper kind of acknowledgement. Read in full, the caption on Salvanechi’s candid night-time photograph has a clear intended purpose; asking for more serious adherence to policies of social isolation, as a tactic to slow the spread of COVID-19. Kleinman and Kleinman’s article acknowledges that images can become a social and symbolic commodity for igniting action and change ix.

When New Zealand’s time came, we also had to make choices about setting policy, and also following policy. About lockdowns and closures and social distancing, and other dramatic social changes. Who can say whether the things we had already witnessed overseas, through the lens and eyes of journalists and everyday citizens on social media, was part of shaping our response?

To conclude…

Whether directly affected or not, in this strange period of human history we have all become ‘online witnesses’ the the COVID19 pandemic. Many of us have absorbed large amounts of numerical and statistical information every day iii, vi. While this information provides easily absorbable overviews of the virus’ impact, it cannot contain or express the more human aspects of this moment in time. However, sprinkled throughout the media coverage, have been images that have also mapped the scope and scale of the pandemic, but in an entirely different way.

Images can hurt us, can wound us. They can also, at the same time, offer an embodied empathetic experience of the suffering of others.. Sometimes they can contribute to changes not only in how we understand the world, but the choices we make in response to it. The images of crematory trucks in Northern Italy expressed the large scale devastation of the virus, at a moment in which the whole world was watching, and deciding how to react. What we owe to these cannot be measured.

References

i National Post, 2020. COVID-19 Italy: Military fleet carries coffins of coronavirus victims out of overwhelmed town. [Online]

Available at: https://nationalpost.com/news/world/covid-19-italy-videos-show-military-fleet-transporting-coffins-of-coronavirus-victims-out-of-overwhelmed-town

[Accessed 09 April 2020].

ii Worldometer, 2020. Italy Population (LIVE). [Online]

Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/italy-population/

[Accessed 20 April 2020].

iii NZHerald, 2020. Covid 19 coronavirus: How virus overwhelmed Italy with almost 5000 deaths in a month. [Online]

Available at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/world/news/article.cfm?c_id=2&objectid=12318768

[Accessed 20 April 2020].

iv Turismo Bergamo, 2020. Visit Bergamo: An Italian masterpiece. [Online]

Available at: https://www.visitbergamo.net/en/news/item/278/

[Accessed 21 April 2020].

v Knox, C., 2020. NZHerald. [Online]

Available at: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12322890

[Accessed 04 May 2020].

vi Worldometers.info, 2020. WORLD / COUNTRIES / ITALY. [Online]

Available at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/italy/

[Accessed 20 April 2020].

vii Salvaneschi, G., 2020. Twitter.com. [Online]

Available at: https://twitter.com/guidosalva/status/1240555847849312256

[Accessed 09 April 2020].

viii Clark, H., 2020. Missing In Action: the lack of a globally co-ordinated response to Covid-19. [Online]

Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/health/coronavirus/120969978/missing-in-action-the-lack-of-a-globally-coordinated-response-to-covid19

[Accessed 04 May 2020].

ix Kleinman, A. a. K. J., 1996. The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times. Daedalus, 125(1), pp. 1-23.

x Stalin, J., 1947. A Single Death is a Tragedy; a Million Deaths is a Statistic. [Online]

Available at: https://quoteinvestigator.com/2010/05/21/death-statistic/

[Accessed 21 April 2020].

xi Frosh, P., 2016. The mouse,the screen and the Holocaust witness: Interface aesthetics and moral response. New Media and Society, 20(1), pp. 351-368.

Posted in ANTH424 (Anthropology of Evil), Case study, Media/political commentary | Tagged anthropology, Corona virus, Covid-19, Covid19, death, Digital, grief, images, Italy, lockdown, morality, pandemic, photography, Ritual, statistics | Leave a reply