NZ Schooling: a case study of administrative evil against Māori?

Written by Etienne DeVilliers, for an assignment on ‘administrative evil’ in ANTH424.

‘Evil’ is a powerful and versatile word. Often when we think of evil, what comes to mind are very deliberate, sadistic or strategic actions. Yet sometimes deeply harmful actions are unintentional.

We all know the consequence of a mistimed word or unthinking act, on an intimate, personal scale. But this is also true on a wider social social scale too, in terms of the negative consequences that can result for certain people or groups, simply from the large scale bureaucratic systems we all take part in. This is what the concept of ‘administrative evil aims’ to capture, and contemporary social scholars argue that more attention needs to be paid to this in the modern, technologically and bureaucratically efficient world we live in (Adams & Balfour 2014).

How does ‘administrative evil’ apply to the NZ schooling system?

Administrative evil is a form of evil which has emerged within a world with a rapidly expanding population which has turned to rationalist systems, such as bureaucracies. Administrative evil relies not on passionate hatred and emotional connections, but rather on a more banal form of evil, characterised by disinterest or unawareness – and thus often lacking in an intentional motive. The example of this that I will be using is the disregard towards the gap in academic results between Māori students and their peers within the contemporary New Zealand schooling system (Page 2008).

I will argue that the harmful consequences of this are a result of administrative evil, where European rationalist approaches are favoured over Māori systems of knowing, resulting in this disparity in educational outcomes.

However I must stress I am not saying this is done intentionally by the vast majority of people – policy makers, teachers, and so on – but instead that it is done because unthinkingly, by people who grow up within these systems and never stop to question them. In short, an unintentional evil – detached from the radical personalities of people like Stalin or Hitler, and embedded instead in bureaucratic systems with in-built disadvantages. There are a few key ways in which this unintentional evil is present in NZ schooling systems, that I will look at.

When bias meets bureaucracy

People of different cultural backgrounds approach situations in different ways. One study showing this in an educational setting, compared how Chinese and American children understood stories in different ways, reflecting wider cultural norms (Wang & Leichtman, 2000). Cultural differences are also present within a New Zealand context, in ways of knowing and learning that are distinct between Māori and European systems.

Despite the country’s aspirations towards a ‘bicultural nation’, the very nature of contemporary schooling institutions in New Zealand is derived from European thought. Much of the comes from past and ongoing perceptions of the superiority of European systems and ways of knowing – the legacy of New Zealand’s past as a colonised nation. Indigenous ways of knowing have been disadvantaged and repressed in numerous systematic ways during this period of political dominance – as is seen among indigenous people in many colonised nations around the world.

Not only the methods and contexts of education, but the way of measuring the success of education, is based on a western set of values, prioritising efficiency and rationalism.

Today the question of funding is important to analysing administrative evil in any given system (Adams & Balfour 2014). Balfour & Adams argue that institutions, in their strive for greater efficiency, can be either constructive or deconstructive – and in a world where much of the making and unmaking of things comes down to money, ventures which are prioritized for funding can become constructed and those that are not become deconstructed. In this way things that are neglected in terms of funding can become disadvantaged.

Such a case can be seen in the case of Pūhoro STEM Academy (Parahi, 2019) a learning support structure for Māori students which has been successful by many measures, but has a hard time receiving funding due to a perceived lack of efficiency and validity. This is despite it’s potential to address the sometimes large gap between cohorts of Māori students’ results and other students (Page 2008, Collins 2019). In fact another recent public discussion in New Zealand highlights that decisions regarding the funding of Māori centered educational systems are further disadvantaged by the gap between Māori students and their peers (Gerritsen, 2019) – seemingly penalising them for both the result and the cause of the inequality. What this emphasises is how these low results have become an obstacle to improvement, due to questions of efficiency, creating a cycle of administrative evil as less and less access to funding is given.

Cultural ‘border crossing’

Modern education systems in most settler nations are built around western systems. Indigenous forms of knowledge can be and are sometimes introduced to these – but typically in a supporting role, within the overall structures and frameworks of European schooling. This can be seen in the earlier example of the Pūhoro STEM Academy (Parahi, 2019), which is a support system present within a more mainstream system that is western in both nature and design.

What this means is that Māori students, and particularly those who grow up with Te Ao Māori as the basis for their way of being in the world, have to move from one system of learning to another, or be at a major disadvantage. In short they have to undergo a sort of cultural border crossing (Aikenhead 1996).

This is allowed to occur as the systems we have in place have become taken for granted as the most efficient form of educating the largest amounts of people. This relates to two characteristics of administrative evil, as proposed by Adams & Balfour (2014). The first is that the system has become taken for granted and as such has become seen as ‘natural’ rather than as a flawed institution. The second is a utilitarian logic that essentially condones a “small” evil (in the disadvantaging of Māori) to support a “greater good” (efficiently educating the largest amounts of people possible) (Balfour., et al., 2014).

Conclusion

When you look at the way that modern educational institutions are structured, it becomes clear that certain methods of learning are prioritized within mainstream schooling, due both to a racist history of belief in the superiority of European thought as well as the distinctive characteristic of rationalism in the bureaucratic systems that deliver and evaluate it.

This can be seen in the way Māori education is managed in contemporary New Zealand. The emphasis on outcomes for the majority, the basis of funding decisions on these outcomes, and the placement of indigenous ways of knowing and learning as ‘supplementary’ or ‘supporting’ to the standardised western systems… all of this connects to the idea of ‘taking for granted’ the natural and beneficial nature of these systems.

In practice this means either accepting, or simply not thinking to question, the ‘small’ evils of disadvantaged Māori students, against the ‘greater’ gain of the majority. For all of these reasons, mainstream schooling in New Zealand is a fitting example of administrative evil as it can function, insidiously, in contemporary post-colonial nation.

References

- Aikenhead, G.S., 1996. Science education: Border crossing into the subculture of science.

- Wang, Q. and Leichtman, M.D., 2000

- Page, R., 2008. Variation in storytelling style amongst New Zealand schoolchildren. Narrative Inquiry, 18(1), pp.152-179

- Balfour, D.L., Adams, G. and Nickels, A., 2014. Unmasking administrative evil. Routledge pg 3-22.

- Gerritsen, J., 2019. RNZ, New Zealand retrieved from: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/national/396560/poor-results-for-maori-pasifika-lead-to-funding-cuts-for-education-providers

- Collins, S., 2019. New Zealand Herald. New Zealand., retrieved from: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12226060

- Parahi, C., 2019. Stuff., New Zealand., retrieved from: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/education/110470040/phoro-a-popular-academic-programme-for-mori-will-run-out-of-funding-in-april

Fire and Flood: Grounding disaster, trauma, and emotion

I recently read Sociologist Timothy Recuber’s (2016) book, Consuming Catastrophe: Mass Media in America’s Decade of Disaster. It is a great book, and I loved it particularly for acknowledging that media is not just informational, but involves aesthetic and performative cues for emotional response. Recuber draws on case studies of 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina, among others. His writing is specific to the USA and acknowledges its scope as such.

I recently read Sociologist Timothy Recuber’s (2016) book, Consuming Catastrophe: Mass Media in America’s Decade of Disaster. It is a great book, and I loved it particularly for acknowledging that media is not just informational, but involves aesthetic and performative cues for emotional response. Recuber draws on case studies of 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina, among others. His writing is specific to the USA and acknowledges its scope as such.

As an Antipodean social anthropologist, I am struck by the need for a cross-cultural and de-centred lens on these topics. There is space for ethnographic studies that highlight the locally situated nature of disaster and disaster-response – the way the narratives, symbols, words and meanings that make sense of catastrophes around culturally grounded and particular,

Black Saturday: reviewing art on the anniversary of disaster

Last week I attended a talk by Dr. Grace Moore, called ‘The Art of Recovery’. Before moving to Otago’s English Department, Dr Moore worked with the ARC (Australian Research Council) Centre for Excellence for the History of Emotions, her research focussing on fire in Australian historical writing and art. But timing and location meant her response also engaged heavily with the devastating Victorian bushfires of ‘Black Saturday’, in 2009. On this 10-year anniversary of the event, she presented some pieces from a collection of art created by survivors.

Last week I attended a talk by Dr. Grace Moore, called ‘The Art of Recovery’. Before moving to Otago’s English Department, Dr Moore worked with the ARC (Australian Research Council) Centre for Excellence for the History of Emotions, her research focussing on fire in Australian historical writing and art. But timing and location meant her response also engaged heavily with the devastating Victorian bushfires of ‘Black Saturday’, in 2009. On this 10-year anniversary of the event, she presented some pieces from a collection of art created by survivors.

William Strutt’s oil painting ‘Black Thursday’ (1861). Referencing the largest fires ever recorded in Australia, taking place in Victoria 1851.

Dr. Moore’s work makes some fascinating comparisons between this, and 19th century European colonists’ narratives and paintings of bushfire. As such she has been able to highlight some of the moral frameworks and social relationships (i.e. heroism, mateship) that have made sense of bushfires in a culturally-specific way. She notes also that there is a rich tradition of depicting fire among many indigenous Australian communities, which would beg deeper research.

The connection between Moore’s talk and Recuber’s book struck me, in that both addressed representations of disaster (and its aftermath), and also that both discussed the role of emotion and affect as they circulated through particular mediums of communication.

Emotion and trauma: inside, outside, on the page and screen

In Dr. Moore’s talk at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, art was framed as something used to ‘confront’ and ‘work through’ trauma. It is ‘cathartic’, and ‘therapeutic.’ The vested interest in such processes, after trauma, is not entirely individual. Amidst controversy about accountability and the inadequacies of long-term support, Grace noted the investment of local government in programmes that allow people to ‘channel their emotions’.

I could also say a lot here, from an anthropological perspective, about the culturally-grounded metaphors of emotion that this all relies on, and in particular the hydraulic metaphors of emotion. These are central to psychodynamic frameworks that emphasise the destructive potential of un-expressed (‘bottled up’) emotions, and the moral and therapeutic values of sharing (‘venting’) emotion.[i]

I could also say a lot here, from an anthropological perspective, about the culturally-grounded metaphors of emotion that this all relies on, and in particular the hydraulic metaphors of emotion. These are central to psychodynamic frameworks that emphasise the destructive potential of un-expressed (‘bottled up’) emotions, and the moral and therapeutic values of sharing (‘venting’) emotion.[i]

I have also written about the distinction between ‘channel’ and ‘vessel’ metaphors of emotion.[ii] In this case I think it is the intersubjectivity of affect that the frequent appearance of ‘channel’ metaphors hint at. They highlight art as not only a personal process but a relational one, a channel for survivors to connect with other people who were not present, across what is often framed as an ineffable void of experience.

Image from the DAX Centre. Source: http://castlemaineart.com/artists/konii-c-burns/konni-c-burns-dax-centre/

Alternatively perhaps the art itself is the vessel, the receptacle, which holds the emotion channelled into it. Indeed Moore noted that emotion and memories are “embedded” into the work. Regional exhibitions focussed on ‘Recording and Collecting Black Saturday’ and the longer-term efforts of DAX Centre to collect these works (and others by victims of broadly-defined ‘trauma’) could be analysed through this lens. It certainly opens up some interesting questions:

- Do these paintings and sculptures represent the materiality of suffering?

- What then, is the political or moral impetus to hold it and preserve it? To communicate it? To view, experience, or consume it?

There is considerable work still to be done examining the ‘moral economy’ of disaster communication: in mass media, and social media. Recuber’s book includes some particularly interesting work on the ‘digital archives’ that formed around the 9/11 and to Hurricane Katrina. It occurs to me that these, and the exhibitions and collections Dr Moore on, can be seen as a deliberate (and ‘high culture’) institutionalisation of the spontaneous shrine that is increasingly a mark of postmodern collective grief.[iii]

Drawing close to the flame: Empathy and its limits

Recuber talks about the ‘aura’ disaster has; the ‘haunting traces of the real’ that it leaves (p16, 26, 90). Are these possible ways to understand the social practice of collecting and preserving ‘trauma’ art?

Recuber’s idea of ‘empathetic hedonism’ also recalls itself here– “in which the desire to understand the suffering of others is pursued doggedly, through always necessarily unsatisfactorily.” (p9).

Recuber notes particular kinds of ‘stylized and idealized’ empathy evoked by mass media coverage of disaster in the contemporary USA (p19). Once again I believe comparative attention to locally situated forms of empathetic engagement in other places would be beneficial. There are undoubtedly some differences, for example, between the capitalist performative merchandise Recuber describes around the Virginia UniTech Shooter, and the patterns of charity, volunteerism, and witnessing/spectatorship specific to Black Saturday.

Stories (including Dr Moore’s own) of watching weather changes in nearby cities create what appears to me to be a distinctive, embodied, and locally-grounded experience of witnessing, mediated by the sight, smell, and taste of smoke.

In examining art made by children’ affected by the Black Saturday bushfires, Moore also poignantly highlighted the way their experience was often mediated by windows – in cars, as they fled, or in schools where they lived with constant view of devastation after the event. Windows featuring in art are indicative of “intensity, shielding, seeing” she points out. This alludes to a bigger question in the communication of catastrophe – the value (and risk) of seeing. Of empathy itself. The question of vicarious traumatisation.

In my own work with youth workers in Canterbury, after the Christchurch quake, metaphors not only of vessels and channels, but also of boundaries, were common in the stories of care, emotional labour, burnout and compassion fatigue I recorded.

Moore’s talk, I noted, included art by one psychologist who counselled survivors of Black Saturday and framed her art around experiences of “emotion oozing red and sad”. The ‘contagion’ model of emotion is heightened when it is extremely traumatic circumstances in question.

Sometimes keeping the channels, the windows, ‘open’ is experienced as dangerous, overwhelming, even when there appears to be a moral imperative to do so. Other times the desire to draw closer to disaster seems to overcome the distance that is safety. But all of these responses occur in situated local worlds – with their own history, their own geography, and their own socio-political contexts, as Recuber and Moore variously highlight.

In emphasising context and comparison, the anthropological lens has value here too. I am eager to see more work that ‘grounds’ disaster, and the communicative practices it generates, in this way.

Written by: Dr Susan Wardell

References:

[i] Lutz, C., White, G.M., 1986. The Anthropology of Emotions. Annual Review of Anthropology 15, 405–436. https://doi.org/10.2307/2155767

[ii] Wardell, S., 2018. Living in the Tension: Care, Selfhood, and Wellbeing Among Faith-based Youth Workers. Carolina Academic Press.

[iii] Magry, P. & Sanchez-Carretero, C. (2007) ‘Memorializing Traumatic Death’, Anthropology Today, 23(3): 1–2.

Women ‘blue’ and bleeding: Witches in contemporary East Indonesia

**Originally published on the ANTH424: Anthropology of evil blog, 22nd June 2018**

Written and visual accounts of witches have changed dramatically across cultures and time. Witches were once described by Europeans in the sixteenth century as old and evil, with wrinkled and deformed features, and are now being depicted in contemporary popular culture as feminist figures who have a pale complexion, and are glamorous and beautiful [1][2]. The visual traits of contemporary witches of East Indonesia are quite distinct from what we encounter in these European historical accounts and in popular culture.

Witches, known as dukun in Indonesia have played a fundamental role in the lives of many East Indonesians, and have impacted how they structure their communities[3]. In this post I analyse how their visual traits and characteristics relate to Mary Douglas’s[4] ideas about the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution. Douglas argues that the body is a symbol of society that requires order and classification, and by referring to East Indonesian witches, one can distinguish this.

In some areas of East Indonesia, there are no distinct visual traits that set apart witches within their communities. Konstantinos Retsikas ethnography [3] concerning sorcery in East Java, Indonesia, noted that both the instigator and the sorcerer remain hidden in fear of being killed. People can only rely on rumours and whispered accusations to identify witches within East Java. As a witch, blending in is the safest approach. At the same time, they share the same motives of envy, greed and jealousy that is common in everyone, challenging people’s ability to accurately recognise the witches within their community.

In some areas of East Indonesia, there are no distinct visual traits that set apart witches within their communities. Konstantinos Retsikas ethnography [3] concerning sorcery in East Java, Indonesia, noted that both the instigator and the sorcerer remain hidden in fear of being killed. People can only rely on rumours and whispered accusations to identify witches within East Java. As a witch, blending in is the safest approach. At the same time, they share the same motives of envy, greed and jealousy that is common in everyone, challenging people’s ability to accurately recognise the witches within their community.

Although due to this lack of distinct visual traits, Retsikas found that in East Java sorcery accusations always tend to focus on one’s relatives, neighbours, friends and work colleagues. Convivial intimacy is risky and choosing one’s friends wisely is critical. Hence, their unidentifiable traits protect some witches, but also leads to uncertainty and moral panic amongst the people of East Java. The unmarked body of witches impacts the communities ability to keep things pure and in order, affecting how members of East Java respond to one another in times of conflict. Thus, this reflects on Douglas’s idea concerning how the body, whether marked or unmarked, is a key symbol in identifying how a community functions.

A key trait prominent in Kodi female hereditary witches from the coastal villages of Sumba is their association with “blue arts” [5].

In Janet Hoskins ethnography, she recognised the transformation of Kodi women into witches led to the appearance of the shade blue in and around their body. As she mentioned, “Hereditary witches have “blueness in them”, they are “bluish people” (tou morongo) whose very blood is believed to be in some way poisonous to others… Blueness is said to be deep inside the liver (ela ate dalo) of a witch, a kind of poison that can affect others even without her willing it” [5]: 322. This poisonous trait is a reflection of pollution and signifies the darkness within hereditary witches. When they are exposed to this powerful trait that can harm the community and their formal structure, it pushes witches into the margins. “Blue arts” or “blueness” found internally and externally in hereditary witches sets them apart from other Kodi women, making them vulnerable to discrimination by their community, and powerful at the same time. Thus, their polluting body has the potential to disrupt the communities social structure and create fear amongst people.

Menstrual blood is a powerful characteristic associated with witchcraft.

Both Konstantinos Retsikas and Janet Hoskins ethnographic study explore the significance of menstrual blood and how the substance has impacted how some villages in East Indonesia function today. In the Huaulu community, Hoskins found that they have strict menstrual taboos to protect their people. Menstruating women are required to stay in menstruating huts away from the men until their cycle has finished. Menstrual blood is believed to be a dangerous and contaminating substance of witches, and can lead to men becoming extremely ill if they come in contact with it. Hence, Huaulu women accept this menstrual taboo as it is seen as a way of protecting the men within their community, and keeps their village pure and clean.

Huaulu strict taboo and the significance of menstrual blood for many other East Indonesian villages relates to Mary Douglas’s idea about the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution. According to Douglas, “The body is a model which can stand for any bounded system”[4]: 115. The bounded system in Huaulu expresses anxiety about the body and its fluids, while at the same time it administers care and protection for the group. Some argue that specific parts of the body, particularly menstrual blood symbolises “dirt [that] offends against order”[4]: 2. Although in Huaulu, their community members are effectively engaging with this polluted and “dirty” substance by creating strict taboos around it, leading to the development of relationships and the strengthening of social order. Therefore, the significance of menstrual blood and its association with witches impacts how Indonesians culturally construct their communities.

Although there are no distinct traits that set apart Indonesian witches in some areas, they continue to play a fundamental role for numerous citizens. Their presence within key substances, and power to cause positive change and conflict within one’s life does not go unnoticed. At the same time, their features relate to Mary Douglas’s ideas of the relationship between the body and sociality, purity and pollution in many ways, affecting how people of East Indonesia function in contemporary society.

Written by: Pulegaomalo Muliagatele-Carter

References:

[1] Briggs 2002: p.15 in Mencej, M. (2007) ‘7- Social Witchcraft: Village Witches’. In: Styrian Witches in European Perspective: Ethnographic Fieldwork, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 313-346.

[2] Buckley, C. (2017) ‘Witches in Popular Culture’. [online]. The Open University. Available from: http://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/literature/witches-popular-culture. [Accessed 14 June 2018].

[3] Retsikas, K. (2010) ‘The Sorcery of Gender: Sex, Death and Difference in East Java, Indonesia’. South East Asia Research, 18(3), pp. 471-502.

[4] Douglas, M. (1966) Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge and K. Paul.

[5] Hoskins, J. (2002) ‘The Menstrual Hut and The Witch’s Lair in Two Eastern Indonesian Societies.’ Ethnology, 41(4), pp. 317-333.

We are ritual creatures

The 3 Minute Thesis competition is a lively annual event. This year Marshall Lewis, a Phd student in Otago’s Social Anthropology programme, competed in the University finals. We thought we’d share the content of his excellent presentation on ‘Ritual Design’ with you! …

“If you have goals that are important to you – and I bet you do – then you may want to design your rituals to support your goals. That’s the main idea behind my project.

So, very quickly: what do I mean by ritual, why use it and how might we design ritual?

Marshall Lewis delivering his presentation

Think of rituals as actions that embody and express your beliefs and values – you live your beliefs and values through ritual – perhaps not consciously. You may have waking rituals, hygiene rituals, eating, commuting, working, shopping, pre-game, post-sex, religious ritual – if you’re religious – even binging on Netflix can be ritual-like.

Why is life so ritualised?

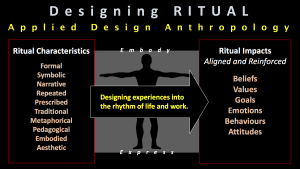

Ritual scholarship is extensive and contentious. I’m focused on two basic propositions: First, there are discernible, family characteristics of ritual – some listed here – and secondly – and here’s why you should care – rituals work. Experimental psychologists have been demonstrating what coaches and drill sergeants have long known: rituals have real impact. For example, they can decrease anxiety, reduce grief, alleviate disappointment. Essentially, they can align and reinforce our beliefs and values.

And knowing that rituals work is real and useful knowledge. What might it look like to take this knowledge seriously: to apply ritual as a strategy or technology to support one’s goals and aspirations? That’s what my project is about. I am applying insights from the interdisciplinary study of ritual — from anthropology, organisational studies and religious studies – to do three things: to defend a conception of ritual as something to be designed; to evolve a practical method for designing ritual, and to apply this method in real-world environments.

Competitors in the 3 Minute Thesis competition are allowed a single powerpoint slide to accompany their 3-minute presentation, and this was Marshall’s image.

Two quick examples: First, I work in a large company that wants a collaborative culture, where people feel empowered to shape the future of the organisation. The question becomes: How might we design organisational rituals such as team meetings and problem-solving sessions if our goal is a collaborative culture?

Secondly, my youngest daughter is starting law school later this month, and she’s designing rituals to help maintain a healthy lifestyle during that period of intensity.

The ritual design method is straight forward, although far from easy. First, clarify your goal and the beliefs and values you want to reinforce (easier said than done!). Then, you design your rhythms and activities using the key characteristics of ritual as design principles. It’s a creative process, though analytically derived.

We are ritual creatures. Ritual is one of the key strategies humans use to bring some order and method to the challenges and chaos of life.

Good luck with your goals! And consider how your rituals can support you!”

“I did this, and this is anthropology!”: Interning at a Community Non-Profit

Though many of us who study social anthropology have a keen interest in helping others, from an uncomfortable seat in a crowded lecture hall it can often be difficult to envision how skills being learnt in the classroom might be applicable in a broader setting.

Here postgrad Social Anthropology student Jordan Webb interviews undergrad student Mika Young[1], about their experience participating in the new HUMS301 humanities internship practicum where they had a chance to translate anthropological theory into ‘real’ world practice at a community organisation; Life Matters Suicide Prevention Trust.

Q. Could you briefly explain the humanities internship paper?

A. I guess it’s about applying what you have learnt in class to a practical context. Every student will go out to an organisation in the community and do some sort of project for them, whether it is research or a practical project. Mine happens to be a mix between the two. Since I already have experience working with organisations in the community, I am helping Life Matters Suicide Prevention in creating a new volunteer training programme.

A. I guess it’s about applying what you have learnt in class to a practical context. Every student will go out to an organisation in the community and do some sort of project for them, whether it is research or a practical project. Mine happens to be a mix between the two. Since I already have experience working with organisations in the community, I am helping Life Matters Suicide Prevention in creating a new volunteer training programme.

Q. What initially drew you to this internship opportunity?

A. I often find it difficult to communicate with people about what anthropology can offer outside of research. So I thought because I am already interested in pursuing community work after my degree that this paper would be a good chance to learn how anthropology works in a practical sense. To get some experience in the area, and then be able to communicate to other organisations, this is what I have done and this is how I can help you.

Q. How did you use your anthropology major during your placement?

A. I drew a lot from Wollcot’s ‘3 E’s’ – experiencing, enquiring, and examining[2]. I think it is really useful drawing on your own experience, doing the research to make sure you are well informed, and also talking to people and including their experiences. So for the organisations I researched on behalf of Life Matters, it was important to hear their perspectives on their existing training programmes. That’s how I try to see anthropology, and when I am going into an organisation I make sure I’ve covered these three aspects

Q. There has been a lot of talk in the tertiary teaching community about capstone papers which consolidate entire undergraduate experiences, how does this relate to your experience?

A. I’d say very well in the final semester of my degree. That was another motivating factor as I think it helps to bridge between academic and public world beyond, particularly with anthropology as it can be difficult to communicate what your skills are. It gives you an example of, ‘I did this, and this is anthropology’!

Q. How has this experience helped you to communicate the potential applications of anthropology?

A. It’s still a challenge! I think this also a difficulty discipline wide, translating anthropology for a the general public. But it is definitely nice having this concrete example of how a practical task could be approached from an anthropological perspective. For example, one thing that I was able to offer was approaching other organisations and translating the knowledge they had already developed, in combination with my own volunteer experience, and contributing an anthropological understanding of why this information is important. It helps the organisation as much as it helps me, providing them with a new perspective.

Q. What was your overall impression of the internship and paper?

A. I thought the biggest challenge would be making the paper count toward my anthropology major, but that aspect seems to have been quite seamless. In terms of, workload, the initial groundwork and planning took a lot of time and effort, but after that three week period it became a lot easier to manage my own workload as I became more familiar with the role and the organisation.

Q. Would you recommend the paper to other students?

A. Definitely! I think it is good practice to make those conceptual links between what anthropology is in the classroom and how you can apply that to different situations. I think a lot of students struggle because anthropology is so broad, everything can be anthropology if you want it to be! So the paper helps with developing both anthropological skills and real world skills, and being able to keep an open dialogue with organisations about how anthropology can be used to help them.

A. Anyone can do the internship, but being open to adapting, developing communication, and being willing to learn will all add to the value of the paper and the role. The advice I would give to others would be to find an organisation that suits your interests and experience, and find out what works best for you.

***

Many of us are interested in translating anthropology: imagining how we might be able to benefit our communities once we finally graduate! As Mika has suggested, the humanities internship paper might be one of the ways to help negotiate this transition, and to develop and refine ethnographic skills through sharing their application with others.

As Mika remarked, “The tools we are learning are helpful in an academic context but they are also just life skills! It is challenging finding applied uses for anthropology, but ultimately it is about being human, right?”

[1] Mika Young was also the winner of the 2018 Sites Senior Student Essay Competition.Their winning essay is entitled ‘Tā Moko and the Cultural Politics of Appropriation’, and will be published in the 2018 December issue of Sites.

[2] Wolcott, H.F. (2008). Ethnography: A Way of Seeing. 2nd ed. Blueridge Summit: Altamira Press.

Dawn Raids: the terror of racism in 1970’s NZ

Posted on by smisu13p

Written by Amy Hema, for an assignment on ‘administrative evil’ in ANTH424.

The 1970s saw some of the darkest times for New Zealand, following the economic crash of the late 1960s. With the first waves of unemployment since the Great Depression, the country was looking for someone to blame. It was was in this context that ‘overstayers’ were deemed to be burden to New Zealand [1]. These overstayers were typically Pasifika peoples who had been actively recruited for New Zealand’s booming labour market, in the early 60’s. Now their deportation was deemed a priority.

To this end in 1974 the New Zealand police began raiding houses suspected of containing overstayers, in the early hours of the morning [2]. These came to be known as the Dawn Raids. Racially motivated, and traumatising for the Polynesian population that were often the focus, this is a moment in the country’s history that largely goes undiscussed, and yet had significant impact on a people group that were marginalised, villainised and targeted by the New Zealand government and police.

A screenshot from a 2015 ‘NZ on Screen’ documentary called ‘Dawn Raids’. The image shows a Pasifika man being taken into custody by police. The documentary represents very recent attempts to acknowledge this part of New Zealand’s history. Source: https://www.nzonscreen.com/title/dawn-raids-2005

Adams and Balfour have written extensively about the relationship between administration and evil; a relationship that is often overlooked, but powerful in enforcing ‘evil’ in the sense of harm against a particular vulnerable group [3]. The Dawn Raids are a prime example of administrative and bureaucratic authority being used to enact this harm.

Discourses of Dehumanisation

Adams and Balfour argue that our daily lives are built upon are taken for granted assumptions; that we take little time to examine the way we are living and the impact it may have. Subsequently, something as fundamental as language and storytelling can make us susceptible to participating in evil without realising it[3].

The dawn raids went largely unopposed by the general public due to the language and discourse used to describe those being targeted in the raids, being unthinkingly accepted.

1970’s National Party Advertisement. Source: Teara.govt.nz

In a 1975 campaign run by the National Party, Polynesians were depicted as aggressive, unwelcome pests who were taking jobs away from deserving Kiwis [4]. The ad told the story of New Zealand as a peaceful nation, one that you would want to raise your children in… until the arrival of immigrants. It claimed that these immigrants became incensed by the lack of jobs, healthcare and education, and turned angry and violent.

In these ads, the blame was being placed squarely on Polynesians; the happy compliant residents depicted were white, whilst the angry individual was brown with a large afro. As such, these ads were used to create a divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’ – those who deserved to be in NZ and those who did not.

The ads created a strong and specific narrative that became a taken for granted ‘Truth’; that Polynesians were taking advantage of New Zealand’s resources and generosity, and that they needed to be removed. Referred to simply as ‘overstayers’, ‘illegals’, and ‘browns’ and presented to the public as over-the-top caricatures, a clear message was sent about who these people were, what they were doing to the country and how they should be dealt with[5]. These catch-all terms enable the individual to refer to a group without acknowledging they are individual humans, who came to New Zealand looking for a better life, instead they are just a collective problem.

In interviews taken at the time of the raids [5], New Zealanders were clearly holding tight to these narratives. As such, they became participants in evil – accepting and condoning through acceptance that a group of people be harmed by prejudicial policies and laws. Standing back and watching it happen.

Through social discourse one can readily observe the way in which language is used to dehumanise and separate the other to allow for the continuation of administrative evil – by actively reinforcing racial stereotypes, create to separate and privilege, New Zealand citizens became passive participants.

The Social Construction of Compliance

In the case of administrative evil, there are hierarchies. Specifically, there are the policy makers and the enforcers. Since the policy makers are a few steps removed from the site of violence, they are able to distance themselves from the reality of the situation. The enforcers however are on the ground, and are active participants.

Interviews with former police officers evidence the same position; they may have been overzealous in their attempts to identify and charge overstayers, but they believed their cause was just, and they were following orders[5]. Adams and Balfour have discussed these attitudes in what they call ‘the social construction of compliance’ – in which the an individual is pushed to perform violence under the direction of authority – whether or not they agree with the process becomes irrelevant as they are no longer acting as an individual but as a cog in a machine.

Adams and Balfour argue that as a culture that has come to place so much value on individualism, the USA has come to expect that when presented with a difficult choice, an individual will stick to their morals and refuse to comply[3]. Did the normative ‘Pakeha’ 1970’s New Zealand share a similar moral system? We know from the overzealous policing that during the dawn raids, the police force became aggressive in their pursual of overstayers. They stopped individuals on the street and asking for identification, in what was essentially ‘stop and frisk’, since the individuals stopped were done so based on the colour of their skin. They raided homes at the crack of dawn, deliberately when individuals and families were vulnerable.

A New Zealand police officer on Lambton Quay, in 1975. Source: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/crime/80132822/decades-investigating-darkest-crimes-does-not-dent-top-detectives-optimism?fbclid=IwAR0gWhk-M76ykJswrlncS8Rsgz4TT6-krw44NeDlEA1LNJ_5jBqvUq6948g

The actions taken by the police and the legal system were extreme, and individuals were being persecuted for minor crimes (such as petty theft) to the fullest extent of the law, at an unprecedented rate – though this was all technically legal, functioning within the system rather than as an exception to it.

Policy makers and police officers put their own opinions and feelings aside to carry out the policies set in place – even if it meant brining harm by enforcing racist ideologies. Whilst there was some push back on the stop and frisk policies, they were ultimately widely enacted by law enforcement[5]. What one can observe from the police tactics at the time is that group morality had the capacity to overrule individualism – a fact not readily embraced by many who believe in individualism.

Concluding Thoughts

Women performing at a Pacifica conference in 1975. Source: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/women-together/pacifica

What is made evident by examining the history of the Dawn Raids in New Zealand, is that administrative evil relies on both passive and active participation. By sharing narratives of harmful individuals who are taking away jobs from more deserving individuals, and upholding policies that allowed law enforcement to act on racism and stereotypes, a culture was created that allowed evil to continue in a way that was accepted by the mainstream populace.

Adams and Balfour stress that administrative evil flourishes under conditions in which people believe in the cause or adopt the ideologies as taken for granted facts – the success of administrative evil then rests in the failure to identify the evil nature of the act until it’s too late.

References

[1] ‘Dawn Raids’. nd. http://dawnraidsnz.weebly.com/

[2] New Zealand History. ‘The 1970’s. https://nzhistory.govt.nz/culture/the-1970s/1976

[3] Adams, G. & Balfour, D.L. (2014). Unmasking Administrative Evil: the dynamics of evil and administrative evil. Sage Publications.

[4] Te Ara (1975) ‘National Party Election Campaign Ad’ https://teara.govt.nz/en/video/2158/national-party-advertisement

[5] ‘NZ/Samoan Dawn Raids’ Documentary New Zealand. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZviIkSxjV0k

Posted in ANTH424 (Anthropology of Evil), Case study, Media/political commentary, Theory and theorists, Undergrad coursework | Tagged administrative evil, anthropology, Aotearoa, cultural politics, Dawn Raids, deportation, immigration, New Zealand, overstayers, Pacific, Pasifika, Polynesian, race relations, state violence, structural violence, violence | Leave a reply