One of the amazing things your body does is to protect itself against disease. When bacteria or viruses invade your body, or you cut yourself, your white blood cells and the substances they produce will protect you, and start healing the damage. The affected area swells up and hurts. This process is called inflammation.

However, when something goes wrong and a body can’t turn off the inflammation response, or it turns on at the wrong time, inflammation can cause arthritis and other autoimmune diseases, and can even lead to cancer.

The signal that turns inflammation on or off in a cell is controlled by a complex network of proteins. That signal is passed between the proteins one step at a time.

Professor Catherine Day, Dr Adam Middleton, and their colleagues in the Otago Department of Biochemistry are very interested in one of the key proteins involved, TRAF6 (TNF receptor-associated factor 6).

A cell first learns that it needs to turn on inflammation through a sensor (receptor) on its outside. Receptors pass the signal to the inside of the cell to a variety of proteins, including the TRAF6 protein. TRAF6 then passes on the message that inflammation is needed to other parts of the cell, so that cell can react appropriately.

Sometimes a cell makes too much TRAF6 protein, or the protein is turned on all the time. This has been linked with various cancers, including melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, colorectal cancer, and myelodysplastic syndromes (a group of blood cell cancers).

The researchers have shown how parts of TRAF6 help it to bind to other proteins to pass on the inflammation signal.

What does TRAF6 look like?

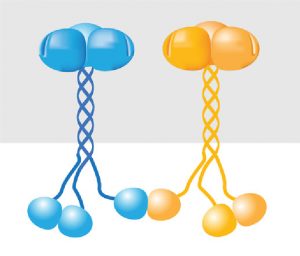

TRAF6 is a long, skinny protein, with a ‘blob’ at each end. It can stick to other TRAF proteins, bringing them together into one big entity.

Once they have done this, they can stick to a protein called Ubc13, and together they build up a chain of signalling molecules called ubiquitin. This chain is responsible for passing on the inflammation signal through the cell.

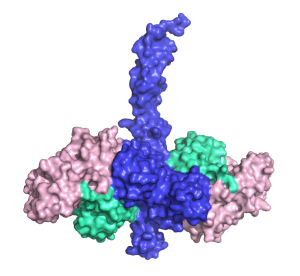

Dr Middleton and Prof Day have found out exactly what the bottom of TRAF6 looks like when bound to Ubc13 and ubiquitin. Their research has revealed which atoms in TRAF6 are responsible for passing on the inflammation signal.

By revealing the fine details of how TRAF proteins cooperate to pass on inflammatory signals, the researchers hope to improve on current cancer treatments and develop new therapies.

Read the full paper here:

The activity of TRAF RING homo- and heterodimers is regulated by zinc finger. Adam J. Middleton, Rhesa Budhidarmo, Anubrita Das, Jingyi Zhu, Martina Foglizzo, Peter D. Mace & Catherine L. Day Nature Communications. 2017; 8(1):1788. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-017-01665-3

Read more about this research in the media:

Synchrotron revealing inflammation secrets

Otago researchers gain new insights into inflammatory signalling mechanisms implicated in cancer