You might have heard of mind mapping. Perhaps one of your teachers or lecturers asked you to make one for a complicated topic. Maybe you scribble them on paper regularly when you’re trying to make sense of something complicated. Or it’s even possible that you’ve missed the mind mapping bus altogether. In this month’s blog, you can learn about what mind maps are, why they could be useful to you and how research has proven their benefits for higher education.

What is a mind map?

We can define a mind map simply as ‘a graphical way to represent ideas and concepts’(1) or ‘a creative and logical means of note-taking and note-making that literally “maps out” your ideas’(2). Both of these descriptions should paint a picture in your mind of words and ideas splayed out across a page in a meaningful visual way. Mind maps also comprise a network of connected and related concepts(3). They are not just random words thrown together on a page. At the core of a mind map is a central idea, topic or issue. Splaying out from that central topic are a number of subtopics, and branching off those are more notes or diagrams. Lines may also be used to connect different branches of the map to show links between ideas, concepts or subtopics.

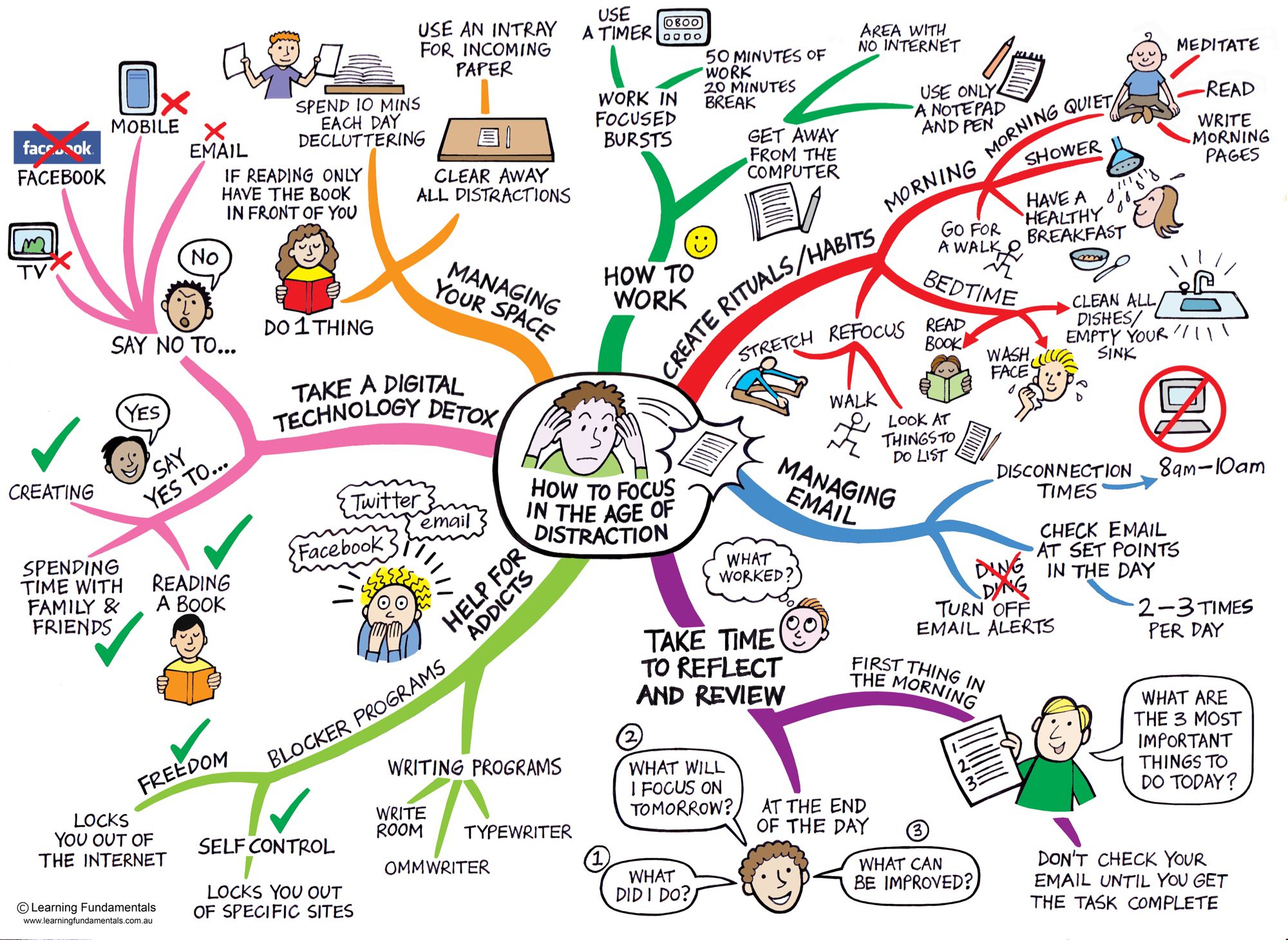

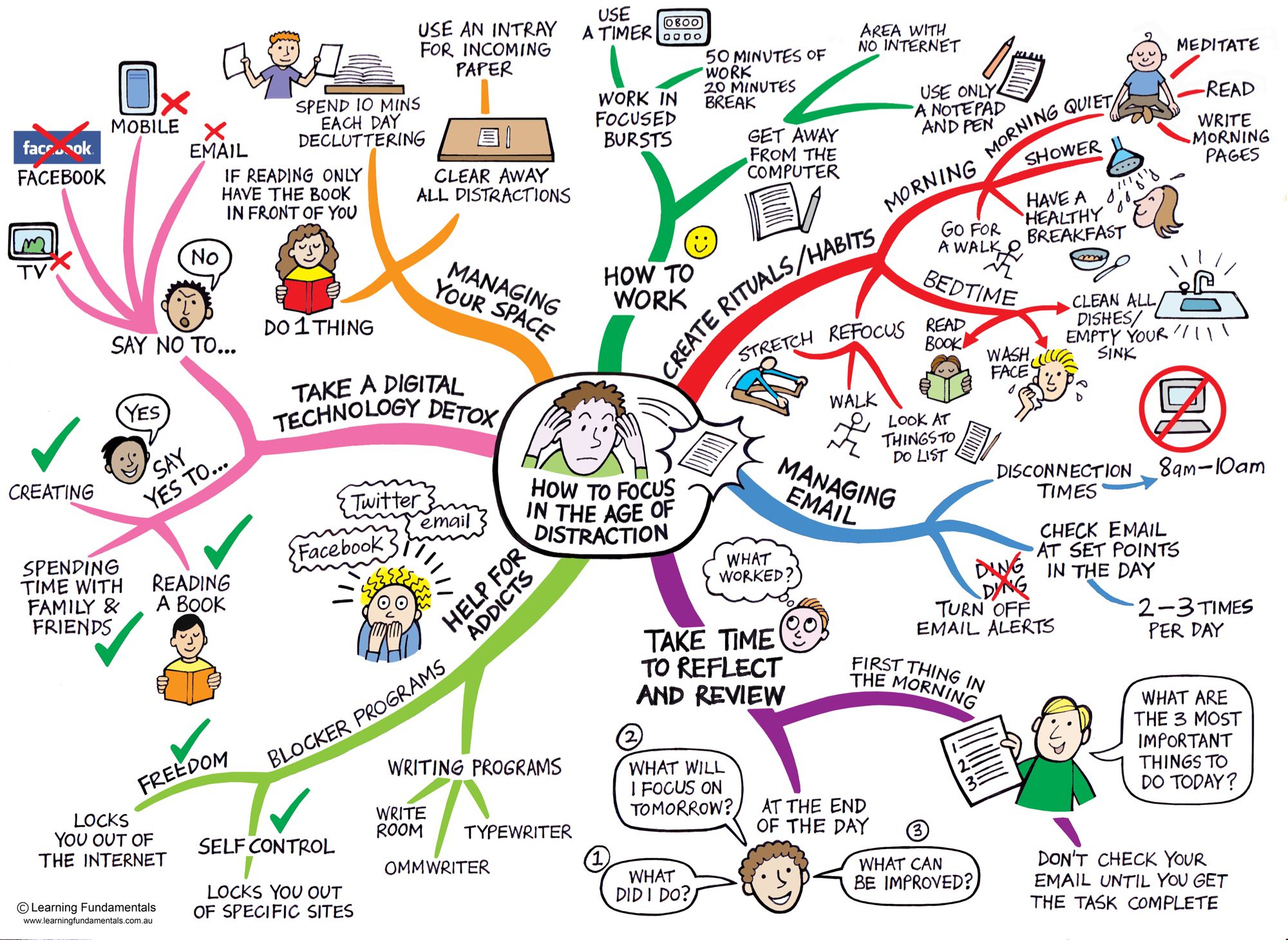

Example of a mind map about how to stay focused in a digital world:

Image from: http://learningfundamentals.com.au/resources/ (4)

As you can see in the mind map above, the creator(4) has chosen a cartoon-like approach with colours, graphics and words to illustrate their ideas about how to stay focused. This mind map would be useful to refer to regularly as a good reminder when you’re not focused.

The most important thing to remember is that a mind map is yours, not anyone else’s. You create it in your own way to visually represent information that is in your mind. No one can tell you that your mind map is wrong, because they can’t see inside your brain where your thoughts and neurons are firing rapidly during the mind mapping process. This map is made by you, for you, in order to safely navigate the often confusing situation of being swamped with too much information. By the time you have made a mind map, you will probably find that your brain has done a download of some (or all) of that information, leaving you free to focus on other things or to take action.

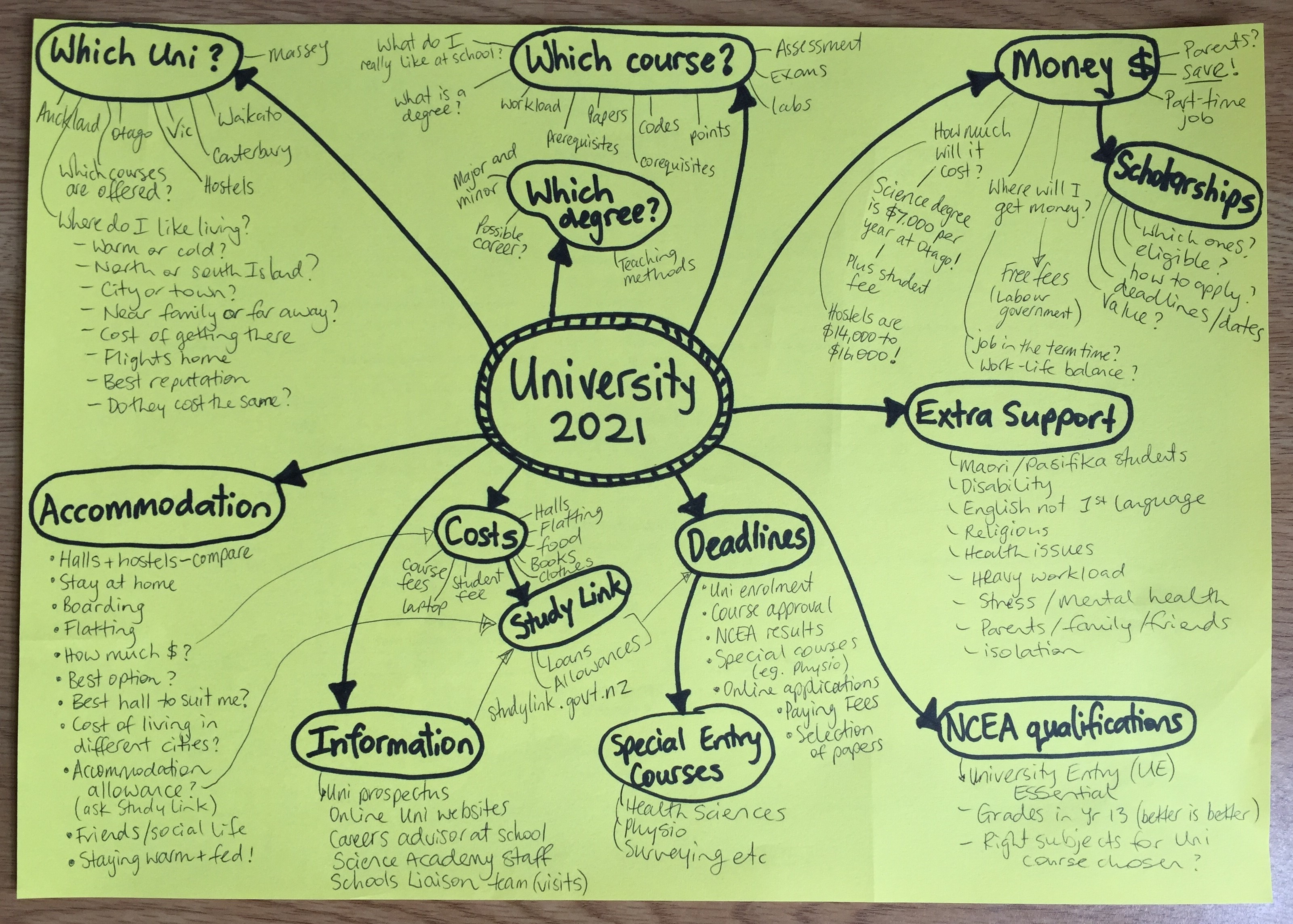

As a demonstration of how mind mapping can work, at least for me and my mind, I decided to choose a topic that I haven’t had to think about for 26 years but which most senior school students will be thinking about all the time: going to university. It’s completely normal to start thinking about university in your last year or two of school. The problem is, as soon as you think ‘university’ you start to think about all these other things like degrees, money, deadlines, careers, scholarships, applications, hostels, etc. All of a sudden, you may start to feel a little overwhelmed because you know almost nothing about anything related to university, yet you feel like you should know more. It may all become too hard, so you do nothing, hoping it all sorts itself out. But it won’t. No one else is going to do the work for you this time. Getting to university is up to you. So instead of sticking your head in the sand, take a deep breath, pick up a pen and try making a mind map.

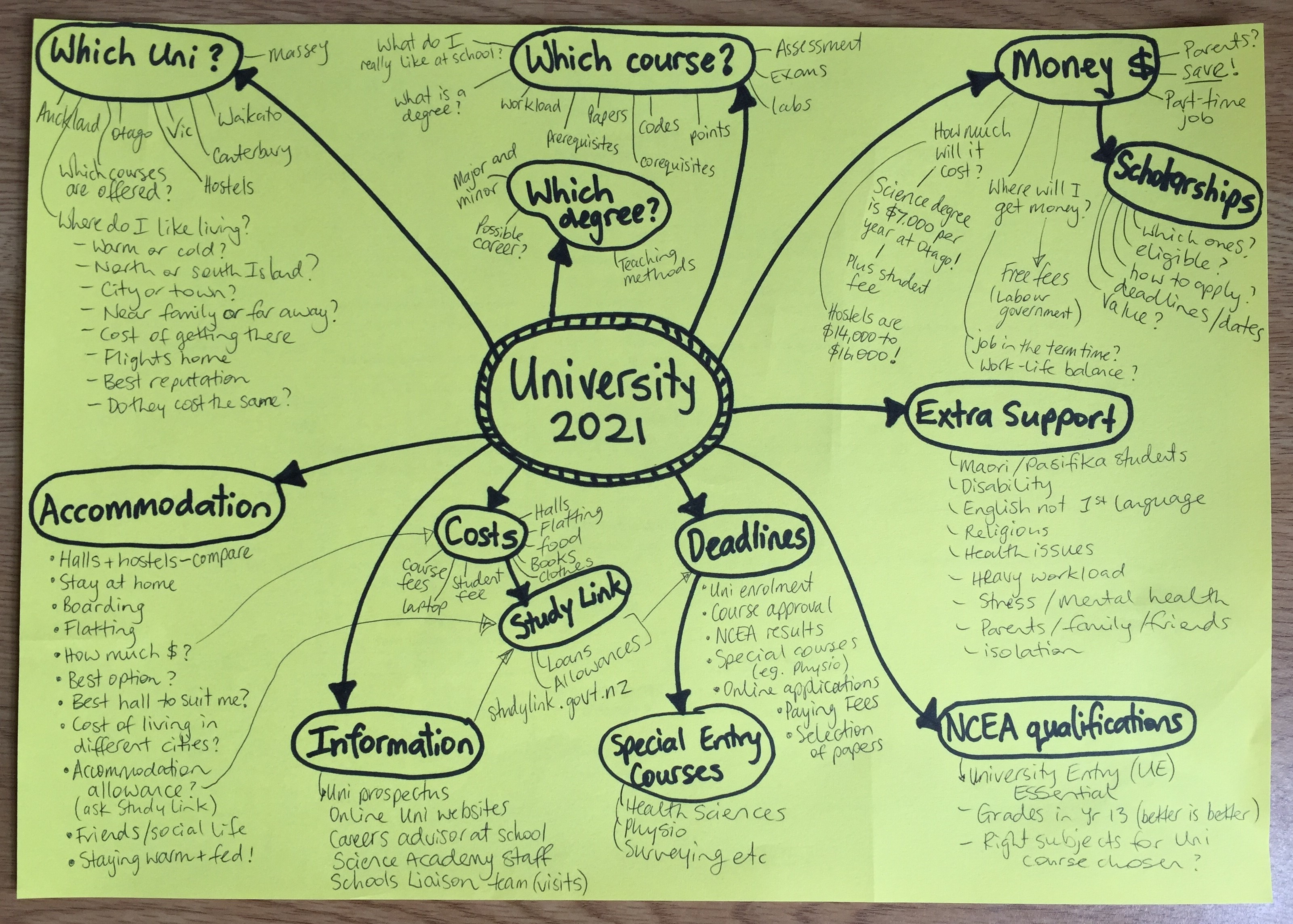

Here is a rough draft of a mind map that I made in about 20 minutes, as if I was thinking about going to university for the first time next year, in 2021:

If I was making this mind map for my future use, next I would colour it in and draw lines between parts that link together, but I didn’t want to make it too messy for you. The only resource I used to make this map was a University of Otago Undergraduate Prospectus booklet(5) which contains essential reading for about-to-be-first-year students.

Back in the 1990’s, before internet searches existed, the Prospectus booklet was the only source of information for planning a university degree. Now, there is so much information out there online that it can be confusing, but the Prospectus should still be your go-to booklet for university planning because it has everything in one place. If I was heading to university next year, I would keep referring to my mind map and work my way through all the things I needed to research and do. I could even make other mind maps which branch off from this one, focusing on ways to make money for university, the pro’s and con’s of each university or which course to take.

The sky is the limit with mind maps!

So, are there other advantages of using mind maps to organise information, other than just to do a ‘download’ from your busy mind? Yes. Here are some of the additional benefits:

- Mind maps can help you to break down complex information and issues, making them easier to understand.(4,6)

When something seems really complex, a mind map helps you to simplify information into some kind of logical picture that your brain can make sense of. Think about a topic which you struggled with in your last year at school. If you’d made some mind maps, could you have presented the information to yourself in a way that was less confusing and more clear? Would that have made it easier to see links between topics and subtopics, or between different concepts?

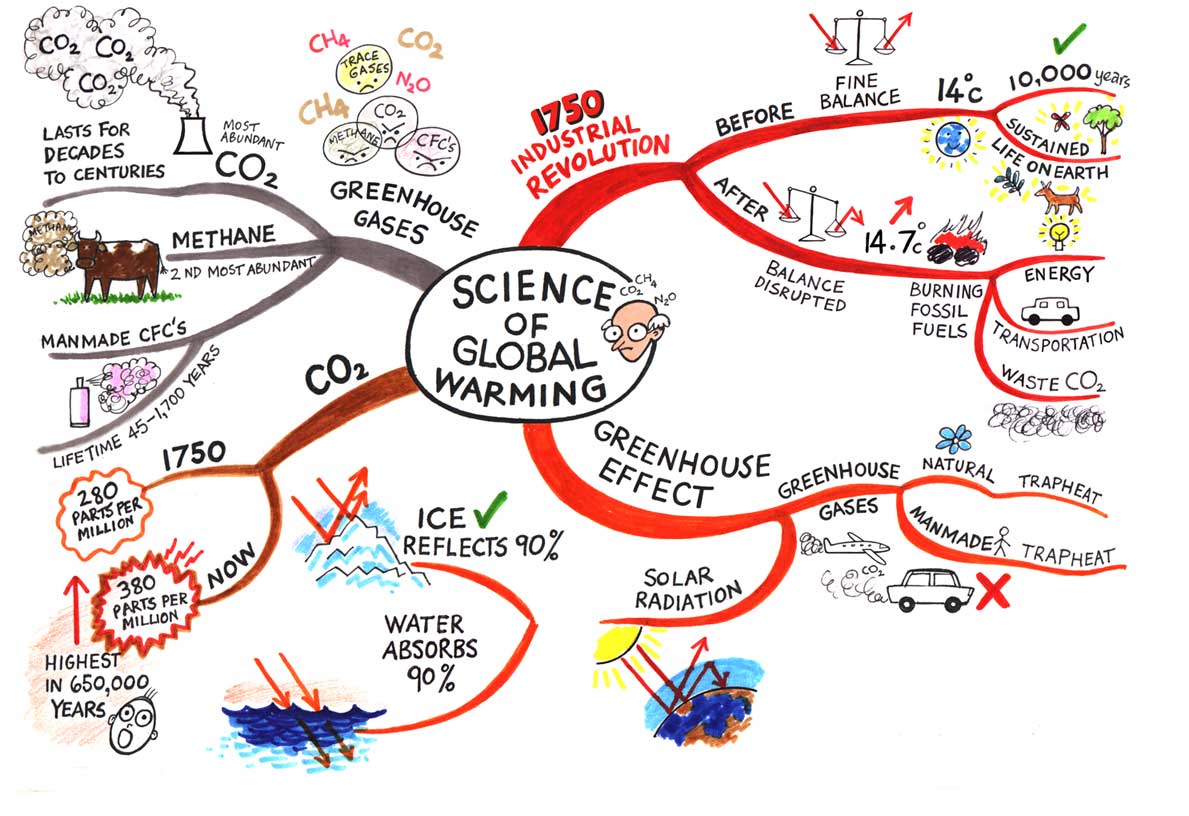

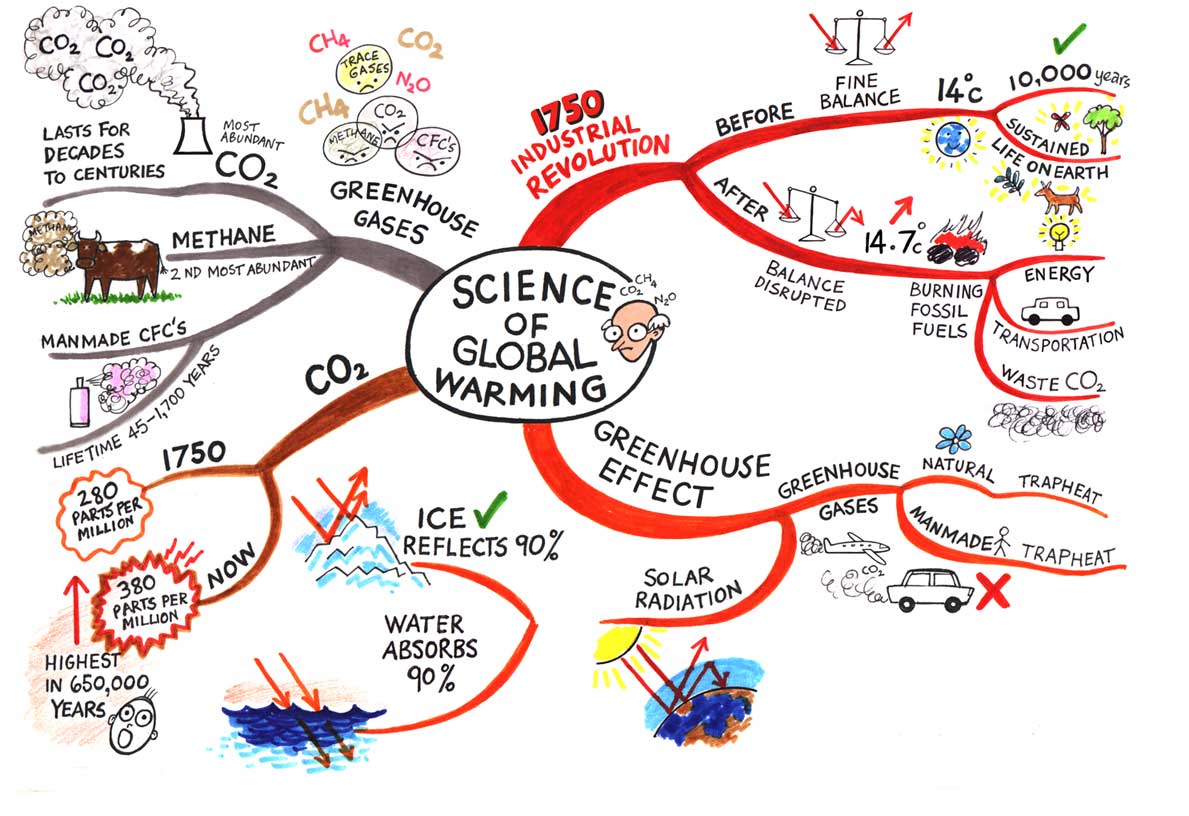

For example, climate change and global warming are complex issues facing our planet and society at the moment. The simple mind map below(4) shows one way of organising some of the key science ideas about global warming in a way which looks interesting and less complex. You can also see clear links between certain aspects, such as the different greenhouse gas emitters or before/after the 1750 industrial revolution. From this simple outline of the main ideas, you could do more research then write a report or essay about the whole topic.

Image from: http://learningfundamentals.com.au/resources/ (4)

- Mind maps improve memory and recall(6)

Our brains easily remember images that we have seen which can then link to other memories. How often have you looked at an old photo of yourself, then suddenly remembered lots of other things which happened during that event? It is generally easier to remember a diagram than a description(3). For example, in an exam, you could quickly sketch the global warming mind map again which you had made earlier in the year or when you were studying. The diagrams and lines in the mind map would then jog your memory of the main ideas for a well-structured essay. Easy!

As a trial, try taking a topic that you have already studied this year and creating a mind map of it. You could either do this using notes or just from memory. Afterwards, pull out your textbook and see what you’ve missed. Add more content, links, diagrams, colour etc, until it summarises all the important key things for that topic. Use it regularly to remind yourself of what was covered during that topic and again for revision.

- Mind maps are a more engaging style of learning(6)

Have you ever spent a whole class period copying notes off the whiteboard or projector screen? If yes, did that method help you to learn? Some learners would say yes. However, a different style would be to create a mind map to brainstorm student ideas of what you already know about a topic or issue, to connect ideas together and work in a group to share ideas between students. This active process would engage everyone in the group, whether they are sharing their ideas or writing on the paper. Talking would generate more ideas. Between you, a whole-page mind map could be created and then shared with the teacher and class. This would be collaborative and engaging, much more so than copying down notes. And you’d be more likely to remember it all too! A scan or photocopy of the final mind map could be taken and shared.

- Mind maps help to show connections between existing knowledge and new learnings

This process is sometimes called ‘meaningful learning’ – making links between prior knowledge and new knowledge(6,7). This process doesn’t always happen by itself, especially when you are young. Mind mapping can help to create meaningful learning if students are forced to find connections between their existing knowledge and new learnings.

For example, take a topic like micro-organisms. If you had to make a mind map now, based on your current knowledge of micro-organisms, what would it look like? How much do you know and how would you organise those ideas on a page in a visual way? Next, imagine if you did a week or two of learning about micro-organisms, either in biology class or doing your own research. If you then took your original mind map and had to add some of your new knowledge to it, the process of doing so would force you to think about integrating and connecting the old and new information in a meaningful way(7) so that the mind map still made sense to you.

Along comes a pandemic like COVID-19 (novel coronavirus). How could you connect that into your micro-organisms mind map? Is it a virus, bacteria or fungi? Will it be helpful or harmful to humans? How and why does it spread? You can see how having one mind map is a good starting point but soon your mind will want to make more of them, branching off the first one. This is a visual representation of you learning and processing new information. Imagine if you took your original mind map to your teacher and said “I decided to add my new knowledge about the novel coronavirus to the mind map that we made in class last week – can you please give me some feedback?” You would make your teacher’s day!

In summary, mind maps are a meaningful learning tool and are definitely worth trying out if you haven’t already. There are lots of free mind mapping websites which are fun to try out: simplemind.eu, mindmeister.com, mindmup.com, sciencemindmaps.com, xmind.net, coggle.it, mindmapping.com and there are some instructions at simplemind.eu which are worth reading(8). Try drawing your own mind map on paper first. The creativity feels great and you won’t be constrained by using any particular template. Good luck – enjoy the mind mapping journey ahead!

Links to references:

Petrina Duncan- Science Teaching Coordinator

Recent Comments