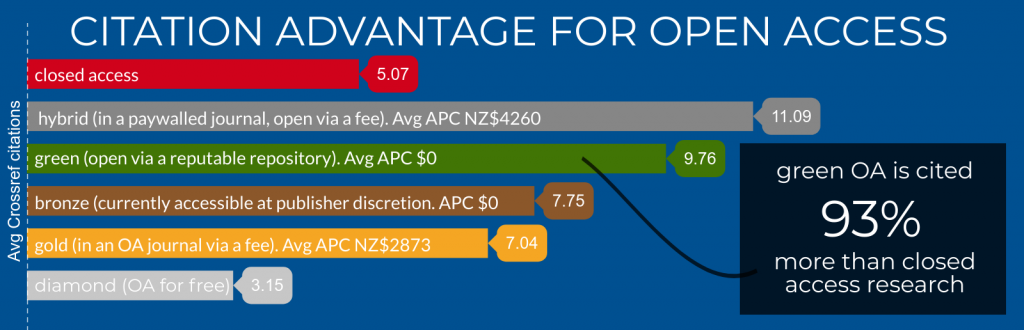

Yesterday we focused on the citation advantage for open access articles, particularly for repository-based articles. Today’s post is a guest post by Fiona Glasgow of our Research Support Unit.

There are many ways to make your work openly available. One option is to deposit your work in an institutional repository; at Otago we have OUR Archive. An institutional repository aims to collect, preserve, and make available digital copies of the intellectual output of an institution.

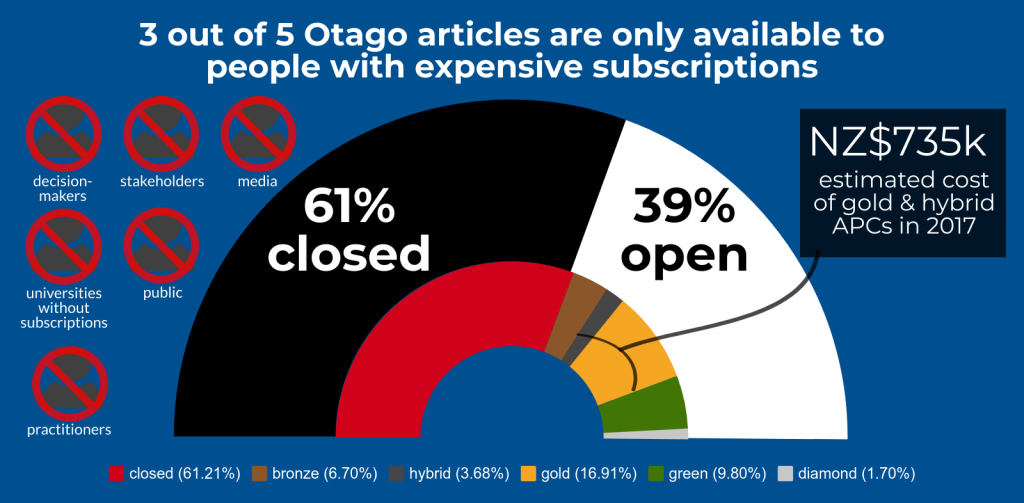

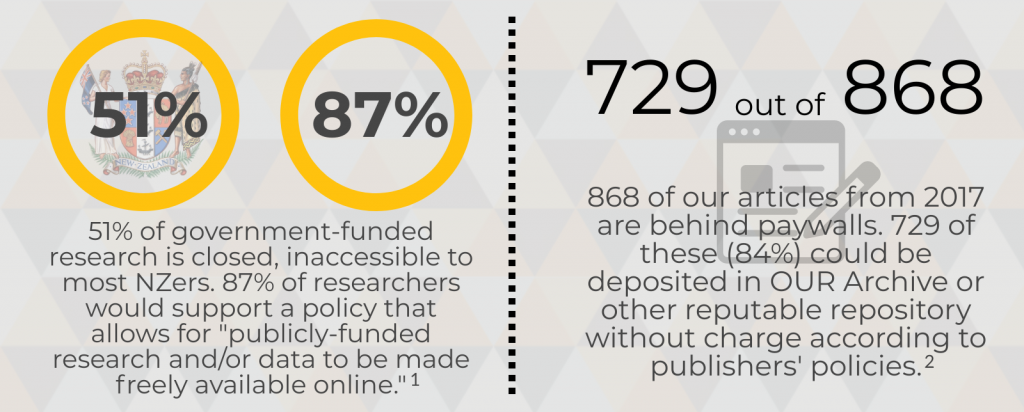

Around 80% of journals will allow you to deposit your research in an institutional repository after a certain time has elapsed from the date of publication – for free! This time period is often 6-12 months, though some but you will need to double check the contract you signed with the publisher or the policies on their websites. Alternatively, you can check this information on SHERPA/RoMEO. This site is a great way to find publisher copyright and self-archiving policies. As mentioned in Richard’s posts earlier this week, 84% of Otago-authored articles from 2017 that are currently behind a paywall could now be legally deposited in a repository.

Some benefits of using OUR Archive include:

- Making your research visible and accessible. Publications are indexed by search engines (Google, Google Scholar, DigitalNZ, etc); this can increase the ranking of your publications in Google searches and help them reach a broader audience.

- Providing persistent access. Each item is assigned a unique handle (persistent URL).

- Gathering statistics on views and downloads. Usage statistics are available for all items and department collections in OUR Archive, and include statistics based on city and country.

Associate Professor Janet Stephenson, Director of the Centre for Sustainability, makes a succinct and compelling case for the benefits of using OUR Archive in this short video interview. She talks about how using OUR Archive has been a critical part in getting the right kind of profile and impact for the Centre’s research outputs, and how increasing access to their work is important for PBRF.

Currently, the majority of research that is deposited into OUR Archive are theses, but it’s possible to deposit a wide range of research outputs, and file types. Over the coming months, the Library is going to focus on increasing the number of non-thesis deposits in OUR Archive. If you have questions or need assistance with the depositing process, please contact your subject librarian.

In early 2020, the Research Support Unit is planning upload-a-thons where librarians will help you deposit your research outputs in OUR Archive. These upload-a-thons also aim to demystify copyright and open access. By going into departments, we hope to tailor the events to your own domain-specific research needs – so bring along any questions you have and works you want to deposit. We hope to see you there!