Inter-Colonial Exchange, Rivalry, and Cooperation in New Guinea: 1890-1945

Maaike Derksen, who is a Visiting Scholar with the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture, will present a research seminar on Wednesday 2 November on her current research relating to New Guinea. The talk begins at 11am in Te Iringa Kōrero (R3S10), on the third floor of Te Tumu: School of Māori, Pacific and Indigenous Studies. We hope to see you there on November 2nd!

Abstract

The 141 Meridian East was established as a colonial border across the Island of New Guinea in 1895. This border divided New Guinea and the adjacent Islands among three foreign powers; the Netherlands, Germany and Britain (later Australia). Nowadays it still effectively acts as one of colonial cartography’s boundaries, separating ‘Asia’ from ‘the Pacific’. In colonial and contemporary maps of (South) East Asia alike, one can see that Papua New Guinea is often curiously absent, while maps of the Pacific stop short of the New Guinea boundary. In this talk I examine the ways in which New Guinea offers an excellent opportunity to explore imperial interconnections and historicize the exchanges, rivalries, and cooperation that resulted.

The last decade, New Imperial scholarship has paid attention to (trans) imperial networks and the connection between motherland and colony within individual colonies. However, this neglects the economic, political, cultural, religious, migratory and cross-cultural entanglements that took place across the peripheries— between ‘neighboring’ colonies. The approach I propose challenges nationalist views of colonialism as well as such rigid views of ‘colonial’ boundaries. With a narrow lens of regional history (New Guinea) combined with the conceptual approach of inter-colonial entanglements I will be able to emphasize the complexities and messy realities of colonial encounters. Especially when entanglements between different actors are highlighted, one can see that colonial boundaries were fluid— that there was movement of goods, knowledge, and people, a formation of networks, shared internal and external threats to security. New Guinea offers numerous cases of cross-border exchange that are worth exploring; the establishment of colonial authority/administration; the networks of traders, pearl divers and bird of paradise hunters, the missionary endeavor of studying, civilizing and converting the indigenous population; the exploring, mapping of the region via scientific and military expeditions; the ‘pacification’ process, the invasion of Japan.

Biography

Maaike Derksen is a PhD candidate in at the History Department and Institute for Gender studies at the Radboud University of Nijmegen. Her research interests focus on colonial history, Christian missions, colonial anthropology, scientific expeditions and the Pacific War in the Dutch East Indies.

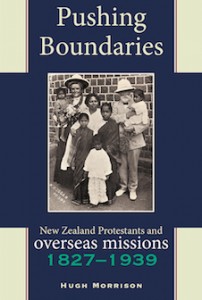

Launch of New Book on New Zealand’s Overseas Missions

Come along to help launch and celebrate Dr Hugh Morrison’s new book, Pushing the Boundaries: New Zealand Protestants and Overseas Missions, 1827-1939, at the University Book Shop (Great King Street), Friday 8th April, at 5.30pm.

Published by Otago University Press, “Pushing Boundaries is the first book-length attempt to tell the story of the evolution of overseas missionary activity by New Zealand’s Protestant churches from the early nineteenth century up to World War II. In this thought-provoking book, Hugh Morrison outlines how and why missions became important to colonial churches – the theological and social reasons churches supported missions, how their ideas were shaped, and what motivated individual New Zealanders to leave these shores to devote their lives elsewhere.

Published by Otago University Press, “Pushing Boundaries is the first book-length attempt to tell the story of the evolution of overseas missionary activity by New Zealand’s Protestant churches from the early nineteenth century up to World War II. In this thought-provoking book, Hugh Morrison outlines how and why missions became important to colonial churches – the theological and social reasons churches supported missions, how their ideas were shaped, and what motivated individual New Zealanders to leave these shores to devote their lives elsewhere.

“Secondly, he connects this local story to some larger historical themes – of gender, culture, empire, childhood and education. This book argues that understanding the overseas missionary activity of Protestant churches and groups can contribute to a more general understanding of how New Zealand has developed as a society and nation.”

Hugh is a historian of missiology, a member of the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture, and a staff member at the College of Education, University of Otago.

Speech to text: Missionary endeavours “to fix the Language of the New Zealanders”

A paper given by L.Paterson at the “Dialogues: Exploring the Drama of Early Missionary Encounters” symposium, Hocken Collections, Dunedin, 7-8 November, 2014.

In this paper I am looking mainly at Thomas Kendall, a member of the first batch of missionaries to New Zealand, and his efforts to create an orthography for te reo Māori. This is of course a topic that other scholars have covered in the past, not least Judith Binney and Jane McRae, but the theme of this symposium is “Dialogues: exploring the drama of early missionary encounters”, held as part of the launching of the new online archive of the Hocken Library’s Marsden Collection, so my paper makes an effort to utilize some of the discussions on orthography from that archive.

I perhaps need to state that I am a historian with some Māori-language skills rather than someone with expertise in linguistics, and I am straying a little outside of my normal period, the 1850s to the early twentieth century, to look at this early missionary period. It is also good that Kuni Jenkins and Alison Jones’s paper at this symposium on the early Missionary-Māori encounter, and their reflection on their 2012 book, He Kōrero: First Maori- Pakeha Conversations on Paper, gives a good insight on how Māori contributed to the development of the orthography. The archive, compiled from missionary letters and journals, is less revealing on their input. The “dialogues” that follow are largely between Thomas Kendall, an on-the-ground missionary, Samuel Marsden, his immediate superior in Sydney, and the Church Missionary Society officials in London. What these texts do showcase is the ease with which historical material can be gleaned from the wealth of material contained in the Marsden Online Archive.

One thing that was important to the early missionaries was to make the scriptures available to Māori in their own language. If Māori were able to read the Bible in their own language, then it would be easier to convert them to Christianity. For this to happen missionaries would have to learn not only how to speak the language, but also to develop a system for writing it down. This would then make it possible to teach Māori how to read, as well as to translate and print the scriptures.

Although not yet ordained, Kendall was the best educated of the missionaries, and as can be seen on a letter written to one of the CMS Secretaries when on his exploratory trip to the Bay of Islands in early 1814, he was well aware that the task would not be easy.

As far as I am concerned, I should know but little of myself, did I not feel conscious of my own inability. Even an attempt to fix the Language of the New Zealanders so that they may be instructed in their own Tongue is a great work; and cannot in the very nature of things be accomplished for some years to come…

[Thomas Kendall to Josiah Pratt, 25 March 1814. MS_0054_035and036.]

We can see here some of Kendall’s early efforts at collecting vocabulary from that first trip.

Ire mi kiki (Come & eat)

Haere mai kaikai [Haere mai [ki te] kai.]

Emmera Ho my why (Bring me some water)

E mara homai [he] wai.

Yahheeyahee pi (A fine night)

Ahiahi pai

[Thomas Kendall to Josiah Pratt, 15 June 1814. MS_0054_043.]

When you compare his renditions with how they might be spelled now (in italics) – we can see that he has utilized English vowel sounds in his spelling. However, he has not been consistent, for example writing the AI sound, as in kai, wai and pai, with either an I or a Y.

The whole process was going to be slow, but the CMS was hopeful. We can see here a letter from one of their secretaries less than a year after the mission was first planted expecting Kendall to be making a start at translating some scripture.

We shall hope to hear that you have made proficiency in the New Zealand tongue; and that the way will be thus prepared by you for the Translation of the Scriptures, when you are joined by a Clergyman who understands the originals. In the mean while we hope that you will prepare portions of Scripture, as well as you may be able; and that the little New Zealanders will, under your kind and paternal care, first learn the rudiments of their own tongue out of the Book of God.

[Rev Josiah Pratt to Thomas Kendall, 16 August 1815. MS_0055_019]

However, it was clear that they thought authorative translations were probably beyond Kendall’s skills, and a “real” clergyman who understood the Greek and Hebrew versions would be needed. By October, 1815 Kendall wrote back to Pratt ”I can speak to them in their own tongue, as yet, but very imperfectly” and he asked if a clergyman could come to help with “fixing the Native Language”. [Thomas Kendall to Samuel Marsden, 27 May 1815. MS_0055_012.]

No clergyman was as yet forthcoming, and in 1815 he produced A Korao no New Zealand, the first book produced for a Māori audience. His grammar is slightly better than his original collections, but we can see in an extract that his spelling continues on the same basis – using English vowels. The italicised text is as it would be spelled today.

Kámatte aou te eaki (I am very hungry)

Ka mate au [i] te hiakai.

Iremi taooa kekone kiei (Come let us sit down and eat.)

Haere mai tāua ki konei kai ai.

[T. Kendall, A Korao no New Zealand (1815)]

Kendall was not a trained linguist, and he wrote the sounds as he heard and understood them. Notwithstanding that Māori may have simplified their expressions to make comprehension easier for Kendall, as can be seen in an example he collected in early 1814.

Shoroe ahaw Dingha Dingha Matta

(Wash your hands and face)

Horoia ōu ringaringa [me tōu] mata.

[Thomas Kendall to Josiah Pratt, 15 June 1814. MS_0054_043.]

But why does it seem so different to modern Māori? We should compare his efforts with modern-day language learners. If you asked an average Japanese people today to say “red” he may well say “led” or “red”. That is because the Japanese language does not distinguish between these sounds, and either L or R can be used in Japanese without changing the meaning at all. Indeed, many Japanese people cannot really hear the difference. Similarly many English speakers have difficulty with other languages, such as Russian or Arabic, that distinguish between sounds that English does not.

Ngāpuhi simply did not differentiate between SH and H, or between D and R. Here in Southern New Zealand, Kai Tahu did not differentiate between L and R, which is why we have Lake Waihola just down the road. But H and SH sounds did sound different to Kendall, so he wrote them down as he heard them.

It is well known that Professor Samuel Lee, the famed linguist at Cambridge University, collaborated with Kendall, Hongi Hika and Waikato in 1820 to create an orthography for te reo Māori. But Lee’s involvement had began several years earlier. In 1818 Lee was already working on Māori grammar, with the aid of Kendall’s A Korao no New Zealand, as well as the services of two Māori travellers, Tuai and Tītere. [Edward Bickersteth and Josiah Pratt to Thomas Kendall, 12 March 1818, MS_0056_076]

It is clear too that Kendall was now leaning towards what were called the “continental” vowel sounds, such as used in Italian. In 1819 he wrote “The Taheitians … pronounce the sounds of the letters and vowels after a similar method very readily.” [Thomas Kendall to Samuel Marsden, 21 April 1819. MS_0056_150.]

Although the missionaries in Tahiti had serious disagreements about an orthography for the Tahitian language, one of their number, John Davies, had developed a system based on “continental vowels”, which Kendall was referring to (Davies, p.77). Kendall wrote later,

On the Sunday after easter I had an opportunity to examine some Taheitian sailors belonging to the Ship King George, and they read the Works of their Missionaries both in print & Manuscript very readily, whereas I am told, the Society Islanders [Tahitians] could never be taught by our [English-based] method.

[Thomas Kendall to Josiah Pratt, 20 May 1819. MS_0056_162.]

In another letter to Pratt he wrote,

Tell Mr Lee that in writing the New Zealand Language I have first fixed the Sounds of the vowels and then formed those sounds, without paying regard to the English or any other orthography.

[Thomas Kendall to Josiah Pratt, 17 May 1819. MS_0056_159.]

Several of Kendall’s manuscripts were subsequently sent to Lee and the CMS. The Secretaries wrote to Kendall,

The New Zealanders first Book [A Korao no New Zealand] has greatly pleased us. Our Orientalist, Mr Lee, is making use of Tooi & Teeterree (who have recently arrived) to form a complete Grammar & Vocabulary of the New Zealand Language.

[Edward Bickersteth and Josiah Pratt to Thomas Kendall, 12 March 1818. MS_0056_076.]

However Bickersteth and Pratt were a little more critical of Kendall’s efforts, when they wrote to Marsden.

Mr Kendall appears to have adopted too many marks of aspiration &c. His system would puzzle the New Zealanders. The whole will require deliberate investigation; and time spent herein in the outset will probably save a great deal in the end.

[Edward Bickersteth and Josiah Pratt to Samuel Marsden, 3 August 1819. MS_0056_188.]

So Hongi, Waikato and Kendall travelled to England in 1820, and while there they worked with Lee to work on an orthography, vocabulary and Grammar, published as A Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language of New Zealand in 1820.

Extract

T. Na tána wahíne ra óki i ó mai. Ke táwahi ra óki e O’ngi, ke Ingland. Ki á no koe i róngo nóa?

P. Ki a no ‘au i róngo nóa.

T. Kóa díro ke ráia; kóa tai ke, méa ka e óki mai.

P. A’i! k’wai tóna kaipúke i éke ai ía?

Modern orthography

T. Na tāna wahine rā hoki i homai. Kei tāwāhi rā hoki a Hongi, kei Ingarangi. Kianō koe i rongo noa?

P. Kianō au i rongo noa.

T. Kua riro kē rā ia; kua tae kē, meake e hoki mai.

P. Āe! Ko wai tōna kaipuke i eke ai ia?

Thomas Kendall. A Grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand (1820).

We can see that there is a clear improvement on Kendall’s earlier work. However, the text still sports dropped Hs, and the use of both R and D. Although there are a few things that don’t look right, most of the vowels are pretty close to modern Māori.

Kendall clearly wanted to take the credit for what was clearly a collaboration between Lee, Hongi, Waikato and himself. He wrote to Pratt:

I thank you for indulging me with the privilege of the instruction of the Rev.d Professor Lee so long. I have now nearly completed my work. The Professor has assisted me very much I could not have done without him.

[Thomas Kendall to Josiah Pratt, 4 October 1820. MS_0498_094.]

So how did their efforts go down with the other missionaries? Kendall’s contemporaries did not like it at all, and their main concern appears to be with the use of the continental vowels. Marsden visited New Zealand in 1823. Kendall had been sacked at this point due to his adultery, and was waiting to leave New Zealand, but he had been told to draw up a vocabulary, using the English vowel sounds.

When I called upon you after our Shipwreck I advised you to employ your time untill [sic] an opportunity for our return to Port Jackson, in drawing up a vocabulary of the New Zealand language in as correct and simple a manner as you could retaining the pronunciation of the English Vowels, as I found the Missionaries met with insuperable difficulties in speaking the language according to the Rules laid down in your Grammer. [sic]

[Samuel Marsden to Thomas Kendall, 14 August 1823. MS_0057_098.]

The debate over English versus continental vowels also occurred in Tahiti, where John Davies was initially outvoted in his attempt to do away with the English vowels (Davies, p.78). As in New Zealand, his contemporaries thought learning a new system would be too hard.

Marsden writing in his journal declared the Grammar to be imperfect, and confusing.

The rules laid down in the Grammer [sic] for the Orthography and Pronounciation of the language is not simple enough for the Missionaries to comprehend— They cannot retain in their memory the sound of the vowels as laid down in the rules of the Grammer— and pronounce them as the Natives can understand them.

[Samuel Marsden’s Journal from 2 July 1823 to 1 November 1823. MS_0177_003.]

I do not see any good reason for changing the sound of the vowels as the New Zealanders can with so much ease sound all the English Alphabet— If in speaking and writing the N[ew] Zealand language the Europeans retain the English pronounciation, the whole difficulty of which they complain, will be removed.

[Samuel Marsden’s Journal from 2 July 1823 to 1 November 1823. MS_0177_003.]

Marsden met with Kendall, who admitted that even he could not follow all the rules. Marsden wrote,

It appeared to me absurd to study Mr Kendalls theory, which he himself could not reduce to practice.

[Marsden’s Personal Copy of the Journal of his Fourth Visit to New Zealand. MS_0177_004.]

Marsden also thought it better if Māori first learnt the English sounds, and then learnt the English language, especially as he thought the Māori language “unchaste”.

I also recommended that all the English terms for such things as the native had never seen, should be introduced into the N Zealand language, that a Sheep should be called a Sheep, a Cow a Cow &c.

[Samuel Marsden’s Journal from 2 July 1823 to 1 November 1823. MS_0177_003.]

Rev Nathaniel Turner, one of the Wesleyan missionaries in the Bay of Islands, also called on Marsden to complain about the 1820 Grammar. Marsden reassured him that it would be going back to the way it was. Turner “expressed much satisfaction” at retaining the English vowels. Marsden opined:

I hope this question will now be at rest, as all are unanimously of opinion that the Vowels should retain the English pronounciation [sic]

[Marsden’s Personal Copy of the Journal of his Fourth Visit to New Zealand. MS_0177_004.]

Marsden’s 1823 visit coincided with changes in the Mission. He brought Rev. Henry Williams to New Zealand and Williams soon after became the effective leader of the Mission. Less than six months after arriving, the new missionary had decided that Kendall’s grammar was a dud.

We, in Council, have condemned the book called “The Grammar.” I cannot tell what share Professor Lee may have had in the composition thereof, but it certainly appears far from simplicity.

[Henry Williams to the Rev E. G. Marsh, January 27, 1824, in Carleton, p.37.]

The Grammar did however made its way to Hawai’i, where the missionaries there may have used it, as they too grappled with creating an orthography for the Hawaiian language (Schütz, p.251).

Kendall was still living in the Bay of Islands at this stage, but away from the mission, and therefore sidelined from new developments in the orthography. Williams put more emphasis on learning the language, as his biographer suggested “not in the slovenly style in which it may be learned by conversation, but in a scholar-like fashion, ascertaining the rules by which it is governed, compiling a dictionary, and fitting themselves to undertake a translation of the Holy Scriptures” (Carleton, p.32). In this efforts he was helped by his brother William Williams who arrived in 1826, and Robert Maunsell in 1836.

Over the next few years there was a slow adaptation of Māori-language orthography. Take, for example this example from 1826: a Proclamation by the NSW governor.

Ná tóna Excelenei, iá Sir Thomasa Brisabane, ko te Captani, ko te tíno Rángatira wáka shau; o ténei káinga, o New South Wales, me óna tíne motu atu óki, &c. &c. &c.

II. Na te méa, e máha ngá páshua tanga o ngá Mótu, kí te Moana Pocifica; a, kí te Moana tudiana, e nga tángata kíno: á ko ugá [sic] tàngata shóko ká máte iá rátou;

[Books in Māori, 6]

The translation was probably done by the John Butler, who had been a missionary at Kerikeri, but by 1826 was living in NSW. We can see the use of some English words and names, and some of the consonants of the older orthographies, such as the W for WH, SH for H, and D for R.

This was also the case in the example below, an extract from the Wesleyan Methodist Mission version’s of the Lord’s Prayer also printed in 1826.

To matu Matua e noho’na koe i dunga ki te rangi, kia tabu tou ingwa. [Books in Māori, 7]

But it appears that any move to return to English vowels was now over. As we see from these scriptural selections below from 1829 and 1833, within a few years written Māori had almost achieved its modern form.

Ko te tahi o nga upoko.

1 I te orokomeatanga i hanga e te Atua te rangi me te ’wenua.

[Books in Māori, 9]

Ko te tahi wahi o te Kawenata Hou o Ihu Karaiti te Ariki, to tatou Kai Wakaora. Me nga upoko e waru o te pukapuka o Kenehi. Ka oti nei te wakamaori ki te reo o Nu Tirani.

[Books in Māori, 15]

What is notable is that the Williams brothers did not opt for English vowels, but continued with the continental vowels that the 1820 grammar had introduced. The new missionaries, such as the Williams brothers, were far better linguists than Kendall, and developed the orthography to its more usable form. They were aware that the Māori language did not distinguish between D and R, so opted just for the R. Similarly other unnecessary letters such as B, L, and SH were dropped. The one major exception that remained was the use of W or ‘W for the WH sound, as seen above. As Binney points out Kendall did attempt, unsuccessfully, to republish a revised grammar in the late 1820s, in which the WH sound would have been differentiated (Judith Binney. ‘Kendall, Thomas’, DNZB). But it was not until the 1840s that the WH was incorporated into the orthography. It is quite possible that regularizing the spelling, and the spread of literacy, has, over time, also had an effect on how te reo was pronounced, with sounds such as D and L falling out of favour.

In conclusion, Thomas Kendall was right in 1814 when he said that fixing the language would be a great work, and a task that would take some years to achieve. He struggled initially with his English ear, but together with Hongi, Waikato, and Samuel Lee, created an orthography in 1820 that went some of the way to finding a workable system. Their efforts were not appreciated by the other missionaries, who wanted to keep to the old style of writing Māori down. It was really the next wave of missionaries, better educated and more methodical in approach, who improved on Kendall’s work, translated considerable amounts of the scriptures, and who had the most success with their evangelical endeavours.

Carleton, H. The Life of Henry Williams, Auckland, 1874.

John Davies, A History of the Tahitian Mission 1799-1830, edited by C.W. Newbury (ed), Cambridge: Hakluyt Society, 1961.

Jones A. and K. Jenkins, He Kōrero: First Maori- Pakeha Conversations on Paper, Wellington: Huia, 2012.

Kendall, T. A Korao no New Zealand, Sydney, 1815.

Kendall T. and S. Lee, A Grammar and Vocabulary of the Language of New Zealand, London, 1820.

Parkinson P. and P. Griffith, Books in Māori 1815-1900: Ngā Tānga Reo Māori, Auckland: Reed, 2004.

Schütz, A. J. Voices of Eden: A History of Hawaiian Studies, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press,1994.

Celebrating Marsden

It’s been a busy few days at the Hocken Collections with the events around the Marsden Online Archive launch and opening of the associated “Whakapono, Faith and Foundations” exhibition, timed to coincide with the bicentennial of the arrival of missionaries in New Zealand.

Considerable publicity had led to these events. For example:

Tony Ballantyne interview on National Radio

Television One News coverage (watch from 17.37)

Te Karere coverage (i roto i te reo Māori – in Māori)

For all the links see the Marsden Online Archive Storify page.

On Thursday afternoon Kāi Tahu and locally-based Northland Māori welcomed Hongi Hika, a self-portrait sculpture by the illustrious Ngā Puhi warrior. Bernard Makoare and Hinerangi Himiona of Ngāpuhi and Chanel Clarke, Māori Curator of the Auckland War Memorial Museum, accompanied this taonga who was installed in the Whakapono exhibition upstairs in the Hocken Gallery. Click here for the full story.

In the evening a good crowd assembled in the Hocken foyer for both the opening of the exhibition and the official launch of the online archive. The event was opened by David Ellison of the Puketeraki Rūnanka of Kāi Tahu, Bernard Makoare, and Kelvin Wright, Anglican Bishop of Dunedin. Particular praise was given to Gordon Parsonson, present in the front row of the audience, whose painstaking work transcribing the Marsden archives over many decades made the creation of the online archive possible.

The Marsden Online Archive was created by the University Library and Hocken Library, with considerable input from Professor Tony Ballantyne and the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture. This will be of great use to researchers interested in early missionary work, Māori-Pākehā interactions, and Māori culture.

The “Whakapono: Faith and Foundations” exhibition runs till 7 February, 2015.

The following two days were given over to “Dialogues”, a symposium on New Zealand’s early missionary history, held in the Hocken Seminar Room organised by the Centre and the Hocken Collections. This was kicked off with Cate Bardwell and Charlotte Brown of the University Library telling the story of how the Online Archive was created, followed with a demonstration of how to get the most out of the collection.

Three well-known religious historians, Allan Davidson (St Johns), Peter Lineham (Massey) and John Stenhouse (Otago) made up the next session. Allan talked on the “dialogue or disputation” in the first Wesleyan mission at Whangaroa; Peter discussed the Anglican moves into the Bay of Plenty/Waikato district in the 1830s, and how this lead to the sacking of the Matamata Mission Station in 1836; and John focused on Octavius Hadfield, his relationship with his Māori parishoners, and how this influenced his opposition to the Crown’s military actions.

After lunch Angela Middleton (Otago) gave an account of the powerful and influential Hariata, Hongi Hika’s daughter, informed by both historical and archaeological sources. Kuni Jenkins (Awanuiarangi) and Alison Jones followed on with a discussion their interpretation of the encounter at Hohi between Ngā Puhi and missionaries in December 1814. In the afternoon Donald Kerr gave an account of Dr Hocken’s collecting, and how he managed to amass so much of the original missionary papers, now housed in the Hocken Collections. Anna Blackman, the Archives Curator at the Hocken, then gave a talk on exploring the Marsden Collection, and earlier archival practice.

In the evening more people assembled for the launch of Angela Middleton’s new book, Pēwhairangi: Bay of Islands Missions and Māori 1814 to 1845. Manuka Henare (Auckland) formally launched the book, along with speeches by the Rachel Scott, Otago University Press publisher, Sharon Dell, the Hocken Librarian, and Paul Diamond, Curator Māori at the Alexander Turnbull Library.

Listen here to Angela’s Radio New Zealand interview, 4 November 2014.

Saturday was a shorter day. Ian Smith (Otago) gave an account of the archaeological dig and Hohi and how this informs our understanding of this first mission site and its inhabitants. Chanel Clarke and Rose Young (Auckland War Memorial Museum) discussed “Taonga Tuku Iho – Objects in Dialogue”, objects from their collection that spoke to the early interactions between missionaries and Māori.

After morning tea, Lachy Paterson (Otago) discussed Thomas Kendall’s dialogues with Marsden and the CMS on developing a working orthography for the Māori language. Paul Diamond (Turnbull) followed on, bringing to light a Māori vocabulary created by the Wesleyan missionary, Rev James Buller, in the 1830s and what this can tell us the Māori language of that time. After lunch, Tony Ballantyne (Otago) rounded off the symposium with a discussion on how applying new techniques from the field of digital humanities can give new historical perspectives, particularly when working with large collections.

CFP: Colonial Christian missions and their legacies, @University of Copenhagen

This may be of interest…

CALL FOR PAPERS: Colonial Christian missions and their legacies

An international conference to be held at the University of Copenhagen, 27-29 April 2015

Confirmed speakers: Laura Stevens (University of Tulsa), Julie Evans (University of Melbourne), Kirsten Thisted (University of Copenhagen), Alan Lester (University of Sussex), Rebekka Habermas, (University of Göttingen)

Over the past decade the entanglement of mission work and colonialism has become central to representations of Christian missions and their legacies. Indeed, discussions over the role and legacy of both Catholic and Protestant missions are currently taking place both in the global historiography on European missions, and in more localized discussions of missions in a diverse range of post-colonial, and not-yet-post-colonial contexts. Despite disagreement on the precise nature of missions’ legacy, most commentators seem to agree that in social, religious, linguistic and educational terms, histories of Christian missions still have a significant impact on post- and not-yet-post- colonial societies today. This conference aims to take a global look at these histories, their legacies and representations. How are colonial Christian missions remembered or memorialised in different contexts and spaces? How are they forgotten? What voice do indigenous people (Christian and non-Christian) have in these representations? And how can we, as academics, artists, museum directors and educators, move towards representing them in more multifaceted, nuanced, and thought-provoking ways? Any types of representations may be considered including historical, artistic, literary, musical, sculptural, filmic, and papers comparing two or more contexts, or taking a global or transnational approach, are welcomed.

Possible topics include, but are not limited to: the history and legacy of relationships between Christian missions and colonial states; the influence of different aspects of colonial rule (economic, social, intimate, etc), on the ways in which Christian mission was articulated; the legacy of Christian missions for past and continuing relationships between indigenous and non-indigenous Christians within social, cultural and religious institutions; the legacy of Christian missions’ constructions of gender; the legacy of Christian missions’ influence on language and translation practices; the influence of Christian missions on indigenous political or artistic expressions; continuities of ideas, discourses, or emotions associated with mission, from the colonial era until now; efforts to reclaim / rewrite / re-represent mission histories by indigenous or non-indigenous peoples and their reception; issues around dramatization or fictionalization in representations of mission histories; vested interests in the representation of Christian missions.

Please send an abstract of 300 words, along with a short biography (max. 200 words) and CV to Claire McLisky at cmclisky@hum.ku.dk by 31 October 2014.