New Book on Religious Childhoods

Creating Religious Childhoods in Anglo-world and British Colonial Contexts, 1800-1950 is a new co-edited collection from Centre member, Hugh Morrison, and Mary Clare Martin (Greenwich University, UK). This new book, published by Routledge, features children and religion in colonial society contexts such as New Zealand, and aims to develop greater understanding of religion as a critical element of modern children’s and young people’s history.

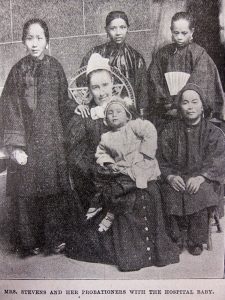

‘Mrs Stevens and her probationers with the hospital baby’, alongside article by Mary Budden, ‘Almora Christian Families’, in LMS Chronicle, July 1895, p. 182 (from Chapter 1, p. 27)

Arguing that religion was an abiding influence (positive, negative and benign) among British-world children throughout the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth, the book places ‘religion’ at the centre of analysis and discussion, while at the same time positioning the religious factor within a broader social and cultural framework. Essays written by an international grouping of scholars focus on a range of geographical settings: America, Australia, Britain, Canada, Fiji, India, New Zealand, South Africa and the South Pacific. The various contexts within which religion shaped childhood in these settings – mission fields, churches, families, communities, institutions, camps, schools and youth movements – are treated as ‘sites’ in which religion contributed to identity formation, albeit in different ways relating to such factors as empire, nation, gender, race, disability and denomination. Chapters on New Zealand include: an examination of southern Dunedin’s religious identity; children’s religious literature published by A.H. & A.W. Reed; and the ways in which religious identity was conflated with civic qualities of sacrifice and service.

Family Emotional Economies & Disability at Birth

Last year, Professor Barbara Brookes (a CRoCC Steering Committee member), contributed a post to a History of Medicine Blog about the ‘complicated emotions surrounding disability at birth’. You can read the Blog post here. In it Barbara traces the emotional responses and experiences of families to disability in mid-twentieth century New Zealand through the dissertations of University of Otago fifth year medical school students in public health. At that time, the students were encouraged to study what was then described as “intellectually handicapped” children, and did so by going into the community and talking to families, but particularly mothers. The dissertations are a rich archive for social history, but are particularly revealing of attitudes to disability, from within and outside the family during the 1950s and 1960s.