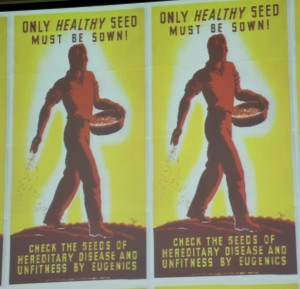

Eugenics at the Edges of Empire

That’s the title of a book that has just been published by co-editors Diane Paul, Hamish Spencer and CRoCC member John Stenhouse. The collection emerged out of a two-day symposium organised by the editorial team at St Margaret’s College in early 2015 and sponsored by the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture. It features contributions from several Centre members (John Stenhouse, Barbara Brookes and Angela Wanhalla), in addition to chapters on New Zealand from a number of other scholars and researchers (Charlotte Macdonald, Caroline Daley, Diane Paul, Hamish Spencer and Emma Gattey). Essays on Australia (Stephen Garton and Ross L. Jones), Canada (Erika Dyck and Alex Deighton) and South Africa (Susanne Klausen), also feature, marking this as the first collection to focus on eugenics as it developed and was applied in the British Dominions. Many congratulations to the editors and all the contributors on the publication of this important collection.

New Book on Religious Childhoods

Creating Religious Childhoods in Anglo-world and British Colonial Contexts, 1800-1950 is a new co-edited collection from Centre member, Hugh Morrison, and Mary Clare Martin (Greenwich University, UK). This new book, published by Routledge, features children and religion in colonial society contexts such as New Zealand, and aims to develop greater understanding of religion as a critical element of modern children’s and young people’s history.

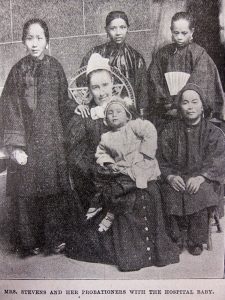

‘Mrs Stevens and her probationers with the hospital baby’, alongside article by Mary Budden, ‘Almora Christian Families’, in LMS Chronicle, July 1895, p. 182 (from Chapter 1, p. 27)

Arguing that religion was an abiding influence (positive, negative and benign) among British-world children throughout the nineteenth century and much of the twentieth, the book places ‘religion’ at the centre of analysis and discussion, while at the same time positioning the religious factor within a broader social and cultural framework. Essays written by an international grouping of scholars focus on a range of geographical settings: America, Australia, Britain, Canada, Fiji, India, New Zealand, South Africa and the South Pacific. The various contexts within which religion shaped childhood in these settings – mission fields, churches, families, communities, institutions, camps, schools and youth movements – are treated as ‘sites’ in which religion contributed to identity formation, albeit in different ways relating to such factors as empire, nation, gender, race, disability and denomination. Chapters on New Zealand include: an examination of southern Dunedin’s religious identity; children’s religious literature published by A.H. & A.W. Reed; and the ways in which religious identity was conflated with civic qualities of sacrifice and service.

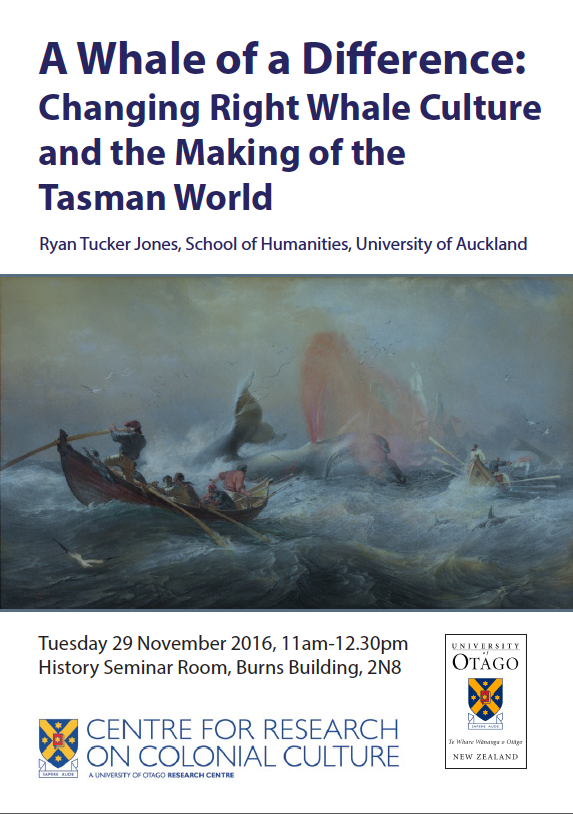

CROCC Seminar: Ryan Tucker Jones

A Whale of a Difference

Changing Right Whale Culture and the Making of the Tasman World

The Centre is hosting Dr Ryan Tucker Jones of the University of Auckland who will be presenting a seminar on Tasman whaling history in relation to British encounters with Māori and Australian Aborigines.

This will be held: 11am-12.30pm, Tuesday 29 November, History Seminar Room (Burns 2N8). Please feel free to come.

Abstract: “This paper examines the impact that changing right whale cultures had on cross-cultural encounters between British colonists, Aboriginal peoples, and Māori in Australia and New Zealand during the era of bay whaling, c.1805-1850. I argue that historians must take seriously the ways that environments (especially living environments) change in order to understand colonial and indigenous histories, and that comparative histories across the Tasman offers an ideal way to think through and document this history.”

Abstract: “This paper examines the impact that changing right whale cultures had on cross-cultural encounters between British colonists, Aboriginal peoples, and Māori in Australia and New Zealand during the era of bay whaling, c.1805-1850. I argue that historians must take seriously the ways that environments (especially living environments) change in order to understand colonial and indigenous histories, and that comparative histories across the Tasman offers an ideal way to think through and document this history.”

Eugenics in British Colonial Contexts

The Centre’s year has kicked off to a good start with “Eugenics in British Colonial Contexts: Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa” in the comfortable facilities of St Margaret’s College, on 7-8 February. This single-stream conference was organized by Associate Professor John Stenhouse (History, and CROCC) and Professor Hamish Spencer (Genetics, and Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology and Evolution), and Professor Emerita Diane Paul (University of Massachusetts Boston, Research Associate, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, and currently William Evans Fellow at Otago).

The Centre’s year has kicked off to a good start with “Eugenics in British Colonial Contexts: Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa” in the comfortable facilities of St Margaret’s College, on 7-8 February. This single-stream conference was organized by Associate Professor John Stenhouse (History, and CROCC) and Professor Hamish Spencer (Genetics, and Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology and Evolution), and Professor Emerita Diane Paul (University of Massachusetts Boston, Research Associate, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, and currently William Evans Fellow at Otago).

After the event was opened by PVC Humanities, Professor Brian Moloughney, Tony Ballantyne (Otago) spoke first on “Colonisation and the problem of Population”. Tony began with the question, when did the Eugenics begin in New Zealand, as its history has various possible beginning points. It was an issue that had significant discursive importance to the big questions of the day, in particular with regard to population, immigration, and political economy.

John Stenhouse (Otago) spoke on William Pember Reeves, the Liberal politician of the late nineteenth century. Reeves, celebrated for his Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration legislation, is less well known for his efforts to restrict the immigration of undesirables, including those deemed to be physically or mentally defective. Reeves was one step beyond public opinion, and his efforts stalled. A watered-down bill, principally anti-Asian, was more successful.

Sir Robert Stout, eminent New Zealand politician and jurist, was the focus of Emma Gattey’s (Otago) talk. A Freethinker and advocate of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, Stout’s interest in eugenics is less well known. An active member of the Eugenics Society, Stout pushed for the segregation of mental defectives from society. Even his own daughter, an epileptic, was held at Seacliff Lunatic Asylum for a number of years.

Stephen Garton (Sydney) talked on the illiberalism prevalent in early twentieth-century Australia, a time now seen when medicine particularly infected by ideology. Ultimately, however, liberal safeguards survive and all efforts at sterilization of mental defectives fail in Australia, and without a scientific consensus, politicians were reluctant to pass contentious legislation. Jane Carey (Wollongong) took a wide view of the issue of eugenics, arguing that race, class and gender are interlinked into eugenist discourses. Eugenics is often seen in terms of national historiography, but was a transnational discourse. Although for some it was about the “English race”, others took a different view, prepared for example, to “breed out colour” through intermarriage.

Click to enlarge. From left, Caroline Daley, John Stenhouse, Hamish Spencer, Stephen Garton, Angela Wanhalla, Jane Carey, Diane Paul, Barbara Brookes, Erika Dyck, Charlotte Macdonald, Susanne Klausen, Rosi Crane.

Baby contests began first in the US in 1854, but soon spread to other countries, including New Zealand. Caroline Daley (Auckland) discussed how initially these shows attracted considerable opposition, but they also appealed to those with proto-eugenic sentiments as indicators as to the quality of the racial stock. Shows took on a more scientific edge, with doctors weighing and measuring the babies. However, Caroline cautioned at reading too much into the eugenist angle, as consumerism was often a motivation for these events, and they continued to be held after eugenics declined in popularity.

Truby King is famous as a health reformer, both in terms of treatment of the mentally ill, and infants’ and children’s health, and as the founder of the Plunket Society that promoted his theory of mothercraft. Diane Paul (Massachusetts Boston) noted that more recently King (and the Plunket Society) have been labelled as eugenist. While it is possible to find some eugenist ideas in his writing, King was also critical of eugenics at times, believing that environmental factors, rather than hereditary, were more important, and how we classify King’s ideas really depends on how we define eugenics.

Susanne Klausen (Carleton) spoke first on the second day, looking at the impact of eugenist theories in South Africa that emerged in the late nineteenth century. One issue that troubled some in South Africa were the poor white Afrikaners, who migrated into the cities, living in slums together with black South Africans. Deemed as less intelligent than other whites, the Race Welfare Society tried to curb their high fertility rate. However, ultimately the eugenics movement in South Africa was relatively weak. In the face of large non-white populations, a white ethnic nationalism prevailed over biological imperatives, with poor white Afrikaners deemed salvageable in the interests of race unity.

Although eugenic discourses percolated through all of Canada, it was only in Western Canada that two provincial parliaments, in British Columbia and Alberta, passed laws legalizing sterilization of the mentally defective. Erika Dyck (Saskatchewan) discussed the situation in Alberta, where most of the sterilizations took place, between 1928-73. It was agrarian feminists who initially pushed for sterilization, but the legislation was strengthened by the Social Credit government, who removed informed consent. More recently it has been claimed that the government targeted indigenous women, but historical evidence for this is lacking, with indigenous health care, run by federal authorities, in general being provided at the most minimal levels.

Charlotte Macdonald (VUW) looked at the history of eugenic discourse in New Zealand. The high point of New Zealand eugenics was the Mental Defectives Amendment Act in 1928, which established a Eugenics Board. “Experts” could be powerful, for example Dr Theodore Gray, the Head of the Mental Hospitals Department, who recommended the sterilization of the mentally unfit, which became Clause 25 in the 1928 Bill. But this legislation was not palatable to all, and was watered down in its final form. Charlotte also looked at the Healthy Body Movement that appeared in a number of the “white” colonies in the 1930s. Although there is an assumption that this reflected eugenist ideas, this was not actually the case, although the perception may have led to its eventual demise.

Angela Wanhalla (Otago) discussed how marriage was also a concern in the discussion leading up to New Zealand’s 1928 legislation. The initial bill included Clause 21 that would have prohibited the marriage of the mentally or socially defective. While some newspapers were broadly supportive, the Anglican and Roman Catholic Churches opposed any state interference in the institution of marriage, and the Labour Party’s Peter Fraser led the fight against the worst aspects of the legislation in parliament. Eugenic discourse did influence divorce law, with insanity grounds to dissolve a marriage, although few used it due to the length of time required. New Zealand’s response was to segregate the mentally unfit rather than sterilization or marriage prohibition.

The last speaker, Hamish Spencer (Otago) also focused on the Mental Defectives legislation of 1928. The first Act, which distinguished between mental illness and defect, was passed in 1911. In 1924, a Committee of Inquiry convened to look into Mental Defectives and Sexual Offenders. A number of academics urged eugenic controls, such as the registration and sterilization of mentally defectives and immigration control, which the commission broadly agreed to. The 1928 legislation also came out of Dr Gray’s Report on Mental Deficiency, compiled after a world tour looking at how other countries dealt with the issue. As noted above, Peter Fraser was a vehement opponent of sterilization. Although the government had the support in parliament to pass this, it was not confident of wider public support and amended the original bill. But it was a very close thing.

All participants felt that this event was extremely productive. Despite differences in how each country applied eugenist ideas, the discourse was transnational. The organizers are now investigating publication options to get their research to a wider audience.

Scots and Indigenous Peoples

We are delighted to announce that Professor Ann Curthoys is giving a free public lecture entitled “Scots and Indigenous Peoples in the Australian Colonies” on Monday 24 November in Castle Lecture Theatre 1 at 3.30. Professor Curthoy’s lecture also doubles as the opening keynote address for the Migrant Cross-Cultural Encounters Conference (24-26 November) being co-convened by the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture, the Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, the Asian Migrations research theme, and the Cross-Cultural Comparative Studies research theme.

Professor Curthoys is one of Australia’s most respected historians. She is an Honorary Professor at the University of Sydney, and a member of the Australian Academy of the Humanities and the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia. In 2013, she was awarded the History Council of New South Wales Annual History Citation that recognises and honours an individual who has made a significant and lifelong contribution to the profession and practice of history. She was formerly an Australian Research Council Professorial Fellow at the University of Sydney (2008-13) and Manning Clark Professor of History at the Australian National University (1996-2008). She has written widely on questions of Aboriginal history, genocide theory, and race relations in colonial and modern Australia. Her current research focuses on Indigenous-settler relations in the Australian colonies. As part of her ongoing research on the British Empire, settler self-government, and Indigenous peoples, she has a particular interest in Scottish-Indigenous relations in the mid nineteenth century, and it is this aspect of her research that she will detail in her public lecture.

She has provided the following abstract:

We can tell the history of Scottish migration to colonial Australia in several very different ways. We might emphasise a generally positive history of struggle and achievement as Scots migrated from one end of the world to another. Or we might narrate a tragic history of Aboriginal dispossession, displacement and replacement in the face of European settlement, a story of violence and great loss of life, and sometimes the destruction of whole societies as settlers fought to secure their hold on the land. Though these two stories are usually told separately, they are, of course, connected – Scots and Aboriginal people encountered one another constantly, and Scottish upward mobility was built on Aboriginal dispossession. Though the task is challenging and difficult, it is worth considering both Scottish diaspora and Indigenous histories together, for when we do, we can better understand some of the complexities of empire and colonisation in the nineteenth century. A focus on Scots can help us deconstruct the categories ‘British’ and ‘settler’, and foreground in new ways the connections between immigrants’ origins and background (in political, cultural, economic, and social terms) and their cross-cultural interactions in the colonies.

In this paper, I discuss the cross-cultural encounters between Scots and Aboriginal people in Australia from the mid 1830s to the mid 1870s. This was the period when a set of struggling British colonies – mostly dependent on convict labour, covering relatively small regions of settlement, and under direct British rule – were transforming into free self-governing democratic colonies dominating vast regions of the continent. While some areas were still experiencing intense frontier conflict and violence, in others the violence had largely ended and a post-frontier society, involving new settler-Indigenous relationships, was emerging. The Scots I consider included both pastoralists and their critics, such as journalists, politicians, amateur ethnographers, and men of the church, and the Indigenous peoples they met are those whose country lay in the two Australian colonies named after Queen Victoria – Victoria and Queensland.