*Trigger warning: Violent image*

I came across this particular image during my own personal exploration into global politics following World War II, in an online article about American politicians. I was shocked after reading into the caption, to find that in this image the man is already dead, with the bullet either still passing through his head, or having just passed through it.

I find this attitude towards this extremely violent situation quite striking. Even with an understanding that extensive exposure can lead to stoicism, it is intriguing to me that one can

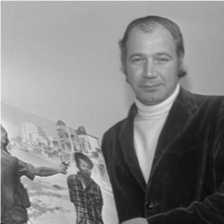

I find this attitude towards this extremely violent situation quite striking. Even with an understanding that extensive exposure can lead to stoicism, it is intriguing to me that one canBy capturing and conveying suffering through visual imagery, the photographer becomes a witness of death, but also a moral actor. Adams believed two people were killed in that instant, “the general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera”6.

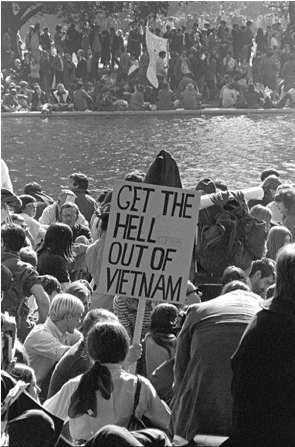

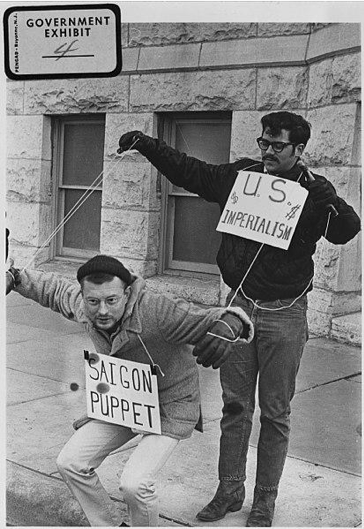

Mobilising Support for Social Action

Kleinman and Kleinman5 emphasise that visual representations of evil can be used to promote social action. Indeed this image slowly became an icon for American activism, and to this day serves as a reminder of the atrocities that arise from political conflicts. This photo was a “classic instance of the use of moral sentiment to mobilize support for social action”. A fellow Vietnam War photographer, David Hume Kennerly, put it this way: “I don’t know that it ended the Vietnam War, but it sure as hell didn’t help the cause for the government – one thing I know for sure, anybody who’s ever seen that photo has never forgotten it”.6

Kleinman and Kleinman5 emphasise that visual representations of evil can be used to promote social action. Indeed this image slowly became an icon for American activism, and to this day serves as a reminder of the atrocities that arise from political conflicts. This photo was a “classic instance of the use of moral sentiment to mobilize support for social action”. A fellow Vietnam War photographer, David Hume Kennerly, put it this way: “I don’t know that it ended the Vietnam War, but it sure as hell didn’t help the cause for the government – one thing I know for sure, anybody who’s ever seen that photo has never forgotten it”.6

The image was used to give a glimpse into the reality for those enduring such brutality, and conveyed a powerful intimacy and desperate message to the people of the USA. It is still considered in the USA to be the “Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War”1.

Appropriating Suffering

This image meant that the death of the Viet Cong prisoner would not go unremembered. As Astor says, “this last instant of his life would be immortalized on the front pages of newspapers nationwide”1. However Kleinman & Kleinman5 also discuss how the suffering depicted in an image can be taken advantage of, particularly in the way that it is distributed and consumed. As is stated in their article, the use of an image to ‘right an inhumane situation’ can be inhumane in itself.

The image of suffering above was used by the American anti-war effort to serve a purpose; as a tool in the process of stopping the Vietnam War, but at what cost? The image may have succeeded in saving many lives by cutting the war shorter, however, the insensitive use of the image was disastrous for some.

For the victim’s wife, Nguyen Thi Lop3, the image served a very different purpose than it’s anti-war role in the US. For her, the use of the image played the role of messenger: informing Nguyen of her husband’s death. In a clip years on, Nguyen is recorded saying in Vietnamese that “a friend of mine brought me the newspaper and then I found out what had happened to my husband”.

The reproduction of this image did not allow this widow the privacy or respect that she deserved. It shows lack of understanding, respect and permission required in the distribution of material. Furthermore we can argue that to share the intimate destruction of human life with such a level of triviality (as glancing past it in a newspaper) de-sensitizes, and reduces from the pain of the victim. Kleinman and Kleinman explain:

“Suffering ‘though at a distance,’ is routinely appropriated in American popular culture, which is a leading edge of global popular culture. The globalization of suffering is one of the more troubling signs of the cultural transformations of the current era: troubling because experience is being used as a commodity, and through this cultural representation of suffering, the experience is being remade, thinned out, and distorted”.5

One effect of this, they argue, is the erasure and distortion of the importance of social experiences of suffering. In this case, the image itself can not inherently convey the contextual political systems that produced it; its literal content is simply a violent act between two individuals. Yet re-contextualised as part of the anti-War effort, it did serve to highlight wider political contexts, such that the social response to the image led to not only condemnation of the violent act by that one soldier, but a change in public attitudes towards US involvement in Vietnam, and eventually a shift in political decisions by the US.

Conclusion

Visual depictions of suffering can be used to make us aware of the suffering experienced in other parts of the world. These visual depictions have the potential to be used as a tool to support social movements. However, the use of images does have its limitations and concerns, transforming the intimate suffering of real people into a tool. It is still up to debate whether this is an acceptable price for social change, and who gets to drive the production and circulation of such images, what they mean, and for what purpose.

References

- Astor, M. (2018, February 1). A Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/world/asia/vietnam-execution-photo.html

- Watson, A. M. (2015). PULITZER PRIZE PHOTOGRAPHY: SAIGON EXECUTION. Retrieved from http://www.newseum.org/2015/05/12/pulitzer-prize-photography-saigon-execution/

- VIETNAM: VIETNAM WAR ANNIVERSARY: MEDIA (2). (2000).. Retrieved from http://www.aparchive.com/metadata/youtube/3061fe038ddb4dece288d433331d7b91

- Adler, M. (2009). The Vietnam War, Through Eddie Adams’ Lens.All Things Considered. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2009/03/24/102112403/the-vietnam-war-through-eddie-adams-lens

- Kleinman, A. (1996) ‘The Appeal of experience; the dismay of images: cultural appropriations of suffering in our times’, Daedalus. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 125(1), pp. 1–23. Available at: https://ezproxy.otago.ac.nz/login?url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/20027351. ISSN: 00115266

- Ruane, M. E. (2018, February 1). A grisly photo of a Saigon execution 50 years ago shocked the world and helped end the war. Washington Post. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/02/01/a-grisly-photo-of-a-saigon-execution-50-years-ago-shocked-the-world-and-helped-end-the-war/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.5374c97d4477

- Prescott, T. L. Appropriation and Representation. Image Journal, (97). Retrieved from https://imagejournal.org/article/appropriation-and-representation/

- Mitchell, R. (2018, March 31). A ‘Pearl Harbor in politics’: LBJ’s stunning decision not to seek reelection. Retrieved April 26, 2019, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2018/03/31/a-pearl-harbor-in-politics-lbjs-stunning-decision-not-to-seek-reelection/?utm_term=.cdd2e6ec89aa