One of the more common, yet insidious hazards that utilitarian cyclists regularly face in urban areas is avoiding, running into or being struck by a car door (usually on the driver’s side). In some jurisdictions, “dooring” has been called the most common type of vehicle/cycle collision (Munro), although these events are undoubtedly under-reported and the risk will vary from place to place. The NZ Road Code, like many other countries, warns drivers specifically about causing a hazard to other road users from door openings.

One of the more common, yet insidious hazards that utilitarian cyclists regularly face in urban areas is avoiding, running into or being struck by a car door (usually on the driver’s side). In some jurisdictions, “dooring” has been called the most common type of vehicle/cycle collision (Munro), although these events are undoubtedly under-reported and the risk will vary from place to place. The NZ Road Code, like many other countries, warns drivers specifically about causing a hazard to other road users from door openings.

Purpose: The purpose of this demonstration project was to determine the feasibility of developing and displaying a publicly accessible interactive web-based map of police reported dooring-related bicycle injuries among New Zealand (NZ) cyclists. This work was performed by the University of Otago’s Injury Prevention Research Unit (IPRU) utilizing data extracted from the NZ Traffic Crash Reports (TCR) recorded by NZ Police and coded by the NZ Ministry of Transport.

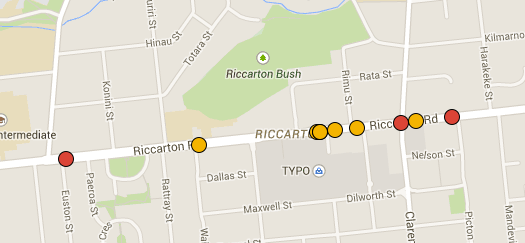

Methods: Vehicle movement data coding was used to select which crashes involving a cyclist injury occurring between 2007 and 2011 were the result of collision with an opening door. TCR records include the spatial coordinates of the crash site and relevant movements of each involved vehicle. The coordinates of each crash site were converted into a format suitable for viewing and sharing in Google Maps™.

Methods: Vehicle movement data coding was used to select which crashes involving a cyclist injury occurring between 2007 and 2011 were the result of collision with an opening door. TCR records include the spatial coordinates of the crash site and relevant movements of each involved vehicle. The coordinates of each crash site were converted into a format suitable for viewing and sharing in Google Maps™.

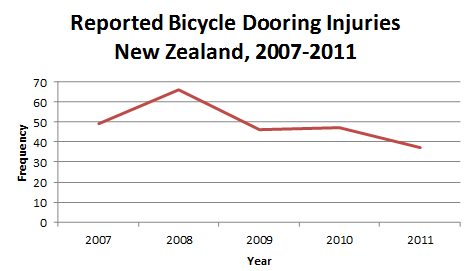

Results: Between 2007 and 2011, 245 cycle dooring injuries were reported in New Zealand (mean = 49/year). These represented 6% of all cyclist injuries involving motor vehicles (compared to 19.4% in Victoria, AU). Doorings comprised a much higher proportion of adult (age ≥19) cyclist injuries, 7%, versus 2% for ages <19. Two-thirds of the cases were male and most victims were adults (see table, below). The mean age for females was 31.4 years and for males 39.1. About 20% of these cases were seriously injured; two deaths were reported (counted within 30 days of crash, by definition).

Cycle vs. Vehicle Door Collisions, NZ, 2007-2011

-

Yellow circles are minor injuries (such as sprains and bruises).

Yellow circles are minor injuries (such as sprains and bruises). -

Red circles are serious injuries (defined by the Ministry of Transport as “Fractures, concussion, internal injuries, crushings, severe cuts and lacerations, severe general shock necessitating medical treatment, and any other injury involving removal to and detention in hospital“).

Red circles are serious injuries (defined by the Ministry of Transport as “Fractures, concussion, internal injuries, crushings, severe cuts and lacerations, severe general shock necessitating medical treatment, and any other injury involving removal to and detention in hospital“). -

Black circles represent fatalities.

Black circles represent fatalities.

Approximate dooring injury crash locations and some clusters along certain roadways can be seen in many of the larger cities (such as Tamaki Drive in Auckland, Victoria St in Hamilton, and Riccarton Rd in Christchurch).

Utilizing the capabilities of Google Maps Street View™ one is also able to ‘drill down’ (once in Google Maps™ click on the spot marker, then choose more/street view from the menu) and note street level photographic evidence of parking facilities, bike lane presence or absence, and other road characteristics near to each crash site. It is noted that the street-level picture itself may not always represent the way the road looked at the time and date of each incident due to the relative and infrequent timing of the Google Street View photography. The Street View also does not always properly indicate which side of the street the crash took place.

Reported Bicycle Dooring Crashes by Age Gender, NZ 2007-2011

|

Age Group |

Gender |

Total |

|

|

F |

M |

||

|

Unknown |

5 | 15 | 20 |

|

0-14 years |

<5 | 9 | 12 |

|

15-24 years |

19 | 24 | 43 |

|

25+ years |

53 | 117 | 170 |

|

Total |

80 | 165 | 245 |

Discussion: We identified and mapped 245 cycle car door injury incidents over this 5 year period. This is undoubtedly an undercount as avoidance maneuvers leading to injury may not have been counted and police reports are known to miss more than half of all crashes involving cyclists (Meulners, Langley). It is difficult to say from these data whether the rate of door crashes per number of cyclists decreased over this period or the numbers of cyclists decreased (or some combination, thereof).

Prevention

- Injury Prevention – Although numerous community informational campaigns have been implemented to address dooring and laws make it illegal to open doors negligently in NZ, the U.S., and elsewhere, such efforts are bound to have little impact. As Munro states in his 2012 review for the Road Safety Action Group Inner Melbourne: “Most education and communication campaigns where car dooring is a component, such as “share the road” style campaigns are probably ineffective as they often run in isolation of other interventions (such as enforcement) and fail the fundamental criteria of being immediate to the behaviour (i.e. car door opening) and intimate (i.e. a direct, personal communication). Furthermore, there is a wealth of evidence from the road safety literature that campaigns which solely provide information, tips or facts are ineffective.” Therefore, effective efforts to reduce dooring incidents should be focused on engineering and infrastructure counter-measures including proper bike lane design and implementation and offering alternative cycling infrastructure and cyclist choices.

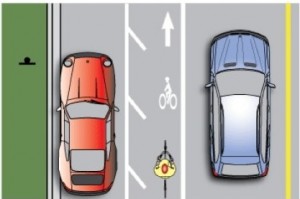

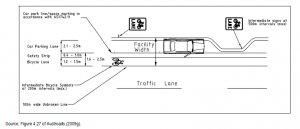

- Bike Lane Design – The key dimension for a bike lane next to a parking lane is not so much the width of the cycle lane, but its reach (i.e., the total facility width) from the curb-side to the outside of the bike lane. For bike lane design guidelines, NZ, looks mainly to Cycling Aspects of Austroads Guides (2011), which uses a desired reach of 4.2 metres (minimum of 4.0m – maximum of 4.5m, page 29). The bike lane itself should be at least 1.5m. The guidelines state: “It is most important to provide a width that is adequate to accommodate parked vehicles, operating space for cyclists and adequate clearance to accommodate the opened door of parked vehicles.” Exactly what is meant by adequate clearance from doors is not stated, though it is clear that in practice many bike lanes do not.

These are recommendations/guidelines. NZ road planners are not required to follow them nor necessarily update older facilities. This is part of the reason why, in many jurisdictions, actual bicycle lane dimensions are sometimes compromised from the guidelines.

Severely compromised functional reach next to a bike lane due to grate, debris and pavement lip.

Substandard widths of reaches and bike lanes always represents a diminished margin of safety. Invariably, these are worsened in the real world by parking and clearance space lost to a large variety of elements such as: Gutter construction, drainage grates, paving overlays,

road debris, street damage, excessive vehicle widths, variable door widths, a range of typical parking (mis)behaviours, parking turn-over rates, as well as cycle and cyclist factors such as bike components, lane positioning and speed.

road debris, street damage, excessive vehicle widths, variable door widths, a range of typical parking (mis)behaviours, parking turn-over rates, as well as cycle and cyclist factors such as bike components, lane positioning and speed. - Improved Cycling Infrastructure – A 2012 review, commissioned by the Road Safety Action Group Inner Melbourne (Munro), listed the following infrastructure measures to reduce the exposure of cyclists to car doors:

- Repositioning or separating bicycle lanes to the kerbside away from the driver-side of parked cars (i.e. “Copenhagen” and protected lanes; see Australian photos, below),

- Removing car parking or extending parking time periods to decrease parking turnover and thus door openings,

- Encouraging and guide cyclists to ride away from the dooring zone through the use of painted buffers, shared lane markings and traffic calming that encourages lane sharing, and

- Ensuring the road space is most effectively utilised by minimizing parking bay width in order to encourage parking as close to the kerb as possible.

Buffered Lanes – Buffered lanes are not encouraged in NZ. Older NZ guidelines say that “Cycle lanes next to parking should not use a “buffer strip” …to separate cyclists from parked cars. Any extra width should be provided in the cycle lane.” While research is lacking, that makes some sense. But other places use them with the painted buffers placed either next to parked cars or between the cycle lane and traffic. Buffers might reduce but don’t eliminate dooring risk, though they offer cyclists some flexibility to ride farther from parked cars. Buffered bike lanes do little to prevent double parking which grows as a problem if bike lanes are too wide.

Buffered Lanes – Buffered lanes are not encouraged in NZ. Older NZ guidelines say that “Cycle lanes next to parking should not use a “buffer strip” …to separate cyclists from parked cars. Any extra width should be provided in the cycle lane.” While research is lacking, that makes some sense. But other places use them with the painted buffers placed either next to parked cars or between the cycle lane and traffic. Buffers might reduce but don’t eliminate dooring risk, though they offer cyclists some flexibility to ride farther from parked cars. Buffered bike lanes do little to prevent double parking which grows as a problem if bike lanes are too wide.

Angled Parking – Where speeds and traffic volumes are low and streets wide, angled parking lanes can almost eliminate dooring risks, but angled parking needs to be carefully designed to avoid backing out conflicts.

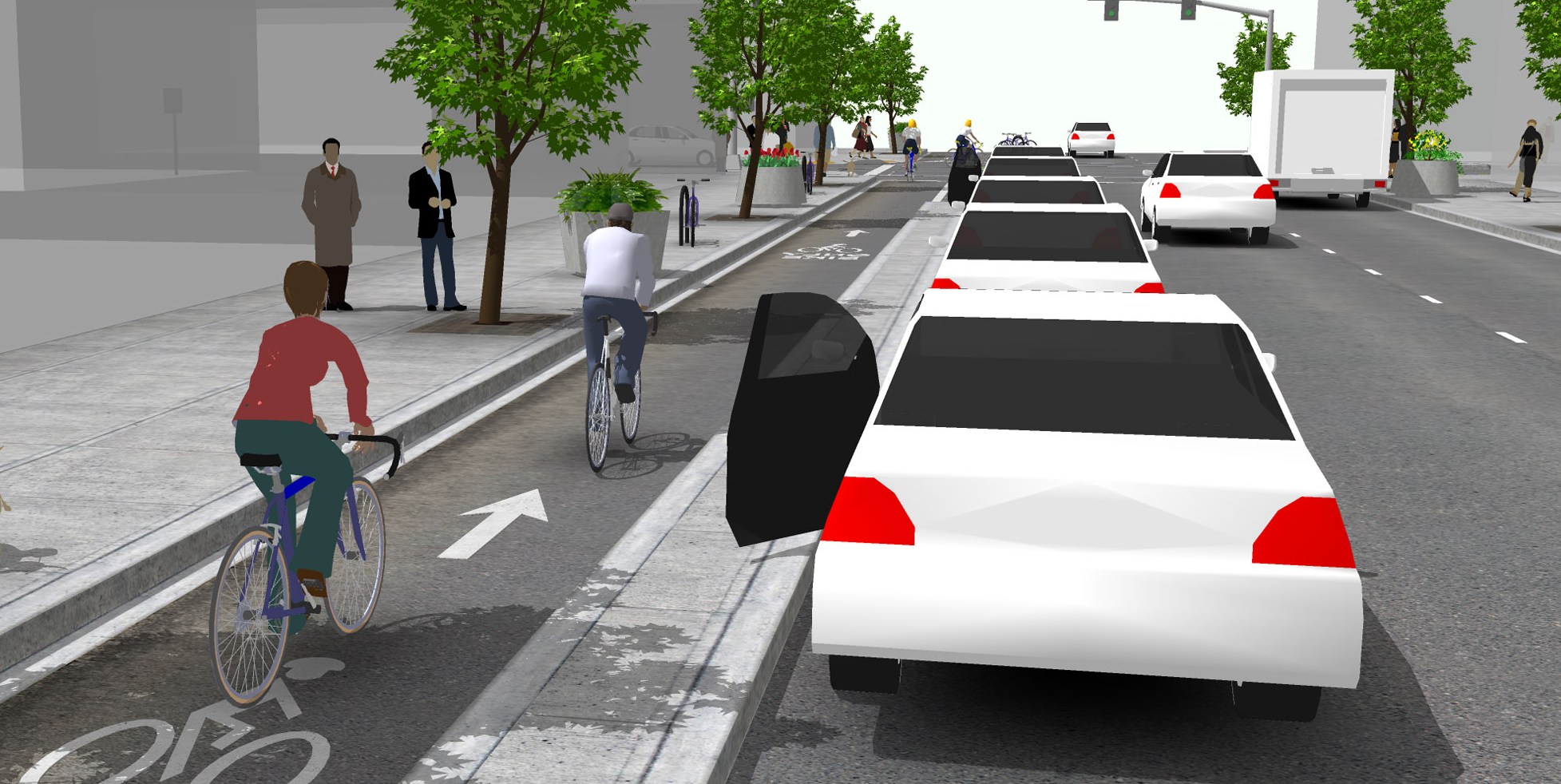

Angled Parking – Where speeds and traffic volumes are low and streets wide, angled parking lanes can almost eliminate dooring risks, but angled parking needs to be carefully designed to avoid backing out conflicts.- Protected Lanes – Real world bike lane implementation challenges, combined with safety and behavioral considerations, are leading more and more transport/cycling safety and engineering professionals (Furth) and cycle advocates in NZ, AU, US and the UK to call for more use of protected (also known as separated/segregated) bicycle tracks in urban areas.

There

There  are many design possibilities (see NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide) for protected lanes, with and without parking. The protection can be parked cars, light or heavy duty bollards, planter boxes, or various types of raised infrastructure. If properly implemented (where roadway widths, traffic conditions, cross traffic and parking policies are amenable) these designs drastically reduce door hazards while appealing

are many design possibilities (see NACTO Urban Bikeway Design Guide) for protected lanes, with and without parking. The protection can be parked cars, light or heavy duty bollards, planter boxes, or various types of raised infrastructure. If properly implemented (where roadway widths, traffic conditions, cross traffic and parking policies are amenable) these designs drastically reduce door hazards while appealing  to a greater number of more traffic adverse potential cyclists.

to a greater number of more traffic adverse potential cyclists.

Recent research (Teschke et al in Toronto and Vancouver (reviewed here) and Lusk et al in Montreal) suggest that properly designed and implemented separated lanes can be at least as safe as regular bike lanes, while being much more popular to both riders and potential riders in preference surveys (Bohle, 2000, Emond et al., 2009, Jensen, 2007, Rose and Marfurt, 2007, Shafizadeh and Niemeier, 1997 and Winters and Teschke, 2010). Removal of parking is indicated where there are driveways and well before the protected bike lane approaches intersections to enhance sight lines.

Conclusions: Using Google Maps™ to map and display locations of dooring incidents can be a useful tool for looking at specific crash patterns with reasonable spatial precision and added capabilities. Streets with higher dooring risks can be readily identified in several specific urban settings with New Zealand’s small population and five years of data. To our knowledge, this is the first national interactive dooring map, while some cities are using similar tools.

Displaying incidents in this format can help with injury prevention efforts by highlighting the issue and potentially influencing planners and road safety officials in ameliorating problem areas through infrastructure changes while showing cyclists and safety advocates where the local dooring hazard areas are. Communities should aim for a connected cycle network with a variety of safe and inviting choices free of dooring threats for all types of cyclists for major destinations.

(Map programming compiled by Brandon de Graaf, concept and writeup by Hank Weiss. University of Otago, School of Medicine, Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, Injury Prevention Research Unit). We wish to thank the several reviewers who offered useful comments on this report.

—————————————–

Cyclists who ride anywhere but on the sidewalk or a bike path are either ignorant or have a death wish.

Sorry that people must be doored in large numbers, or sent to a parapalegic ward, before this will become official policy.

ct (40+ years of safe bike riding)

Great work, one thing i would like to see, as most dooring are probably not reported, is the ability for cyclist to submit this somewhere.

“The purpose of this demonstration project was to determine the feasibility of developing and displaying a publicly accessible interactive web-based map of police reported dooring-related bicycle injuries among New Zealand (NZ) cyclists”

on that front i would say you’ve shown its not feasible – apart from a few specific stretches of road which any local cyclist could have nominated immediately, all they’ve shown is that dooring can and does happen all over the place. that’s perhaps a good point in itself to show that its a widespread problem cyclists face anytime they ride past a parked car, anywhere, but it doesn’t really identify any specific otherwise unknown areas for targetting.

the other obvious feature is that these incidents are clearly grossly under-reported, as is common with all types of accidents involving cyclists being hit.

on the real issue of cycle safety, i agree that education and communication campaigns are ineffective as they are not matched by either enforcement or engineering. it is shameful that even new roading projects are not required to adequately provide for all legal road users.

the “copenhagen” style bike lane between parked cars and the curb scares me hugely. much as cars are a major hazzard to cyclists in urban areas, pedestrians are the worst, regularly stepping out in front of cyclists having not looked beyond a quick glance. where stepping from a car to the footpath nobody will think about looking for cyclists coming up between car and footpath and this will not change for many years of regular accidents. in copenhagen it may work as they have a cycling culture and everyone thinks to look out for cyclists – the whole point is that this is not the case in NZ.

as with many aspects of cycling safety, this is affected by the significant variation in speeds within cyclists – typically ranging from 10km/h to 40km/h or more. the 10km/h cyclist is much like a pedestrian (slower than many runners) so it is appropriate to provide shared foot/cycle paths or cycle paths next to the foor path. the 40km/h cyclist is a similar speed to other road vehicles – noting that legally a cyclist is classed as a road vehicle like any other. at 40km/h there is no chance of visibility in either direction along a narrow lane between parked cars. a cycle lane needs to support cyclists passing each other – the cycle lane next to car lanes allows the faster cyclist to pull out into the car lane which is appropriate since they are travelling at a similar speed to cars anyway.

the best solution all round is shallow angle parking with a defined buffer zone either side of a cycle lane, then the traffic lanes. if space is limited then parking can be on only one side of the road without any loss of parks compared to 2-sided parallel parking.

good to see thought going into enhancing cycling facilities though

Thanks Hank for a useful piece of work. May more of us ride more safely as a result. O’ that’s right government continues to underfund cycling infrastructure. Still, thanks and we will keep right on advocating for smart, safe, sustainable mode choice.

Christchurch City Council recently approved the elimination of cycle lanes required by New Zealand standards and their own Infrastructure Design Standards from new roads in a new Living G/Commercial zone (Yaldhurst Living G). They also eliminated other required safety features and 4m median from the busy commuter road resulting in the roads being grossly below NZ road safety standards NZS4404.

The required cycle lanes and roads were to be at no cost to the ratepayer. They are the developers cost from the multimillion dollar rezoning profits.

Existing cycle lanes now come to dead ends causing the very pinch points and “doorings” that cause the injuries and deaths highlighted in your research.

The Councils failure to implement the required safety standards was brought to the attention of Councils CEO Tony Marryatt, Mayor Bob Parker, and the full Council. Both “bosses” refused to do anything about it and only 4 Councillors had the courage to stand against them.

CEO Tony Marryatt’s semantic response was that the Council was not eliminating these required cycle lanes because the Council was refusing to implement their requirement in the first place.

The injuries and deaths highlighted in your research are largely the result of bureaucratic negligence approving known dangers along commuting routes. If Councils knowingly permit dangerous buildings to be built they are liable for resultant injuries and deaths; they must therefore be liable for approving known death traps on roads when safe solutions are not only viable but are required.

Wonderful work! My father was killed in 2008 when a motorist ‘doored’ him and he fell in to the path of the oncoming traffic. It was the second time he had been ‘doored’, the first time he came of with brusing because it happened on a quieter road. I agree that these indicidents are under reported. I was wondering if there was some form of self reporting, like geonet site, if cyclist would use that?

You can report a bad driver online to the police at this link: https://forms.police.govt.nz/forms/online-community-roadwatch-report/9

There is also 0800 CYCLECRASH (0800 292 532) number used in Tasman District to build a picture of crash hot spots.

Hi, I’d like to propose what I guess you might term a reverse angled parking. It would look like the angled parking, but motorists would reverse into the space rather than drive in nose-in. When they are pulling out, they’d be looking forwards to their right, just like pulling onto a highway from a slip road and should easily be able to see any harder to spot road users.

Of course drivers would need to reverse into the space which is slightly trickier, but no more difficult than reversing into a parallel park.

Any opening doors would only impact other vehicles parked to either side, not anything on the road itself.

I would imagine it would need to be just on the inside lane rather than on both sides as we currently have on some of the main highways in Dunedin. The loss of parks on the outside lane would be somewhat offset by the increased density on the inside due to the angle of the parks. On roads with traffic travelling in both directions, maybe we could restrict parking to one side only?

Anyway, just a thought as it’s an option than I haven’t seen described anywhere & is the best that I (as a cyclist and a motorist) can come up with. Any ideas how I could push this forward?

Cheers

Louise,

Reverse angle parking is a solution that is occasionally adopted when you have a lot of room and slow light traffic. Streets wiki talks about them. I have wondered out loud myself about that option on N Road in NE Valley where dooring remains a hazard. I don’t think it works well on the one-ways given the volume and speed of the traffic there, however.

Pingback: Handy Tips: Avoiding Dooring | Cycling in Christchurch