Healing the Self: Motivational Speakers as Shamans

Written by: Emma Gamson

[Adapted from an essay written for ANTH228/328: Anthropology of Religion and the Supernatural]

Motivational speaking is a category of verbal performance where the goal is to inspire or motivate an audience 12. Motivational speakers tend to share self-narratives, to convey messages of hope, reassurance and success 8. There is no training or certification required; success depend on an individual speakers’ popularity 8, 9.

Tony Robbins is a highly influential motivational speaker whose messages focus on empowerment, self-transformation and “unleashing the inner-self” 14, 7.

Tony Robbins presents his talk ‘Why We Do What We Do’ at the February 2006 TED conference. The image shows Robbins open and powerful stage presence as he addresses as audience. Source: https://www.ted.com/talks/tony_robbins_asks_why_we_do_what_we_do

This post analyses some of Robbins’ performances, to argue that motivational speaking can be understood as a type of healing practice. I apply concepts from the anthropology of religion, such as liminality, communitas, and ritual, to understand how he frames the self, how he establishes legitimacy, and how he enacts healing.

Narrating your self into (a new) existence

Understandings of the ‘self’ varies cross-culturally. Greek philosophers Plato, and later Descatres, as well as much of early Christian thought, supported a dualist view of the person, in which the body is a physical, mechanical and matter of science, and the mind (in which the person or ‘self’ resides) is non-physical, spiritual and a matter of the church 16, 17. Conversely, Freud, Foucault, Sartre and Social Sciences have supported a non-dualism in which the self is made up of a body and mind immediately connected to each other, and both are subject to the influence of society and power 16. In anthropology, the ‘self’ is typically associated with the perception of one’s own existence, and is different to ‘identity’, which is more related to how ones existence is placed in relation to others 17.

People’s sense of their ‘self’ is formed by self-narrative. In other words the stories we tell about ourselves (to others, and to ourselves), have the potential to continually reconstruct who we understand ourselves to be. 6. In this way self-narratives express an individual’s agency. However they also tend to reflect frameworks laid out by wider social structures (e.g. around gender, age, class) 6.

People’s sense of their ‘self’ is formed by self-narrative. In other words the stories we tell about ourselves (to others, and to ourselves), have the potential to continually reconstruct who we understand ourselves to be. 6. In this way self-narratives express an individual’s agency. However they also tend to reflect frameworks laid out by wider social structures (e.g. around gender, age, class) 6.

Robbins uses narrative to convey themes of self-renewal, self-help and power of a true inner self, all of which he claims are controlled by state of mind and worldview 2, 15. His key argument is that “you can sculpt the person you want to be with whatever raw material you have available, so long as you acknowledge the early forces that shaped you” 15.

Processes of self are not just about the mind, but about the body too. In anthropology, embodiment theory emphasises the intimate connection between mind, body and culture (in in fact seeks to challenge these as separate categories, all together). Many motivational speakers also take a holistic view, including Tony Robbins, who treats the mind and body as distinct, but directly influencing each other 15.

Religion, ritual, and self-transformation

Ritual practice is a key feature of religion. Rituals can work to express meaning, and apply religious worldviews to daily life 11. Religious worldviews can form the framework against which individuals develop and create their self-narratives. Religious ritual deeply embeds this frameworks through embodied (implicit) and explicit knowledge of one’s self in the context of the world, consequently influencing how one perceives and acts in the world 11.

Tony Robbins on stage at one of his ‘Unleash the Power Within’ seminars. A three-and-a-half-day event oriented towards helping “you unlock and unleash the forces inside you to break through your limitations and take control of your life”. The image is a snapshot showing Robbins enthusiastic and big gestures that are incorporated into his stage performances. Source: https://www.tonyrobbins.com/events/unleash-the-power-within/

As a motivational speaker, Tony Robbins employs embodied, ritualized action in a way similar to religious practice. His talks verbally lay out a worldview in which individuals have an ‘inner power’. Then his rituals make this true by enacting the ‘unleashing’ of this power with bodily action 8, 15, 14.

Specifically, Robbins his audience to participate through verbal agreement 2, 15. Their vocal articulations are a ritual way of unleashing this power. By getting his audience to respond through an embodied ritual of call-and-response, in his talks and seminars, he is asking them to reposition their own self within this worldview; to re-write their self-narrative according to that. In shifting the framework for their story, he shifts the story and thus the self.

Why does ritual work? Hot coals and big crowds

The effectiveness of Robbin’s performance is contingent on his audience. Religion is a dynamic product of human activity that tends to revolve around a central source of legitimacy or authority, but this must be continuously performed, negotiated, reproduced and validated by participants and audience members 1.

A seminar attendee calmly walks across a path of hot coals, embodying the beliefs and ideas that have been taught by Robbins. Behind cheers him on as they people queue for their turn. Source: http://morewealthandhealth.com/tony-robbins-fire-walk-review-read-fire-walk/

Robbins continuously negotiates and reinforces his authority when he prompt action from the audience. For example, Robbins created a ritualized action of walking over hot coals to show the power of the inner self, which many people have attempted 15. The offer would be absurd if the audience did not reinforce and embody support by actually attempting the walk, thus continuing to reinforce and legitimize the authority of Robbins and his worldview.

One key feature in the effectiveness of motivational speaking, is liminality. Anthropologists understand liminality as an intermediary stage in a ‘rite of passage’ ritual, which typically focuses on shifting someone’s social positionality. Like most motivational speakers, Robbins does indeed emphasizes ‘transformation’. We can argue that he uses his events to create a liminal space in which the possibilities for transformation occurs.

Communitas can be experienced in ‘coming of age’ rituals, rock concerts, sports games, prisons, religious events, and more.

The liminal stage is the ‘in between’ stage, and when lots of people are experiencing this together, it can lead to a state called ‘communitas’. Communitas is a state of anti-structure, where usual social boundaries and identities temporarily fall away, and people feel joined by bonds of common feeling 18. Liminality and communitas can both facilitate, acute moments of self-transformation.

Despite the perception of motivational speaking as an ‘individualistic’ form of healing, communitas appears to emerge again in ritualised acts in which Robbins’ audience participants respond collectively, rather than individually 18. After all, would it work the same if we was alone in a room with someone? His seminars can become a space of communitas – the audience all are temporarily separated from their normal lives, and united with others in their intense experiences in that room. It is together that they are remade.

Healing: is Tony Robbins a shaman?

People attending Tony Robbins talks seek empowerment. It is fair to infer then that they come with some sense of deficiency or disempowerment – while their bodies may be healthy, their ‘self’ is in need.

Religion is one framework of meaning that can help individuals make sense of what it means to have or to lose health, what it means to be lacking or whole10. While not a religion, Robbin’s talks similarly offer a framework of meaning that locate the cause of problems, and their solution, within a particular set of symbols and ideas: i.e. about ‘inner power’ and how to ‘unleash it’, and what effects (on both body and mind) this can have.

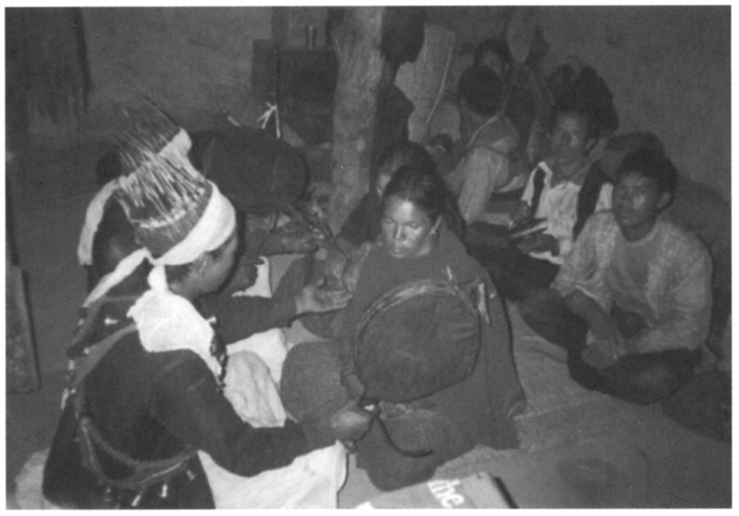

A shamanic healing ceremony, showing the jhākri (Nepali shaman) alongside a woman undergoing the healing process. Behind is a group who are also participating in and supporting the ritual (Sidkey 2010, p219)

There are similarities in particular with the way Toby Robbins works, and what anthropologists have observed of some shamanic traditions. For example, Yolmo shamans define health by the aesthetics of balance, wholeness and harmony to determine health 4. These values are embodied in the daily life of Yolmo society, embedding them in the body and shaping sensory experiences of health 4, 5. Shamans may conduct rituals involving trance states with vivid imagery to deal with illness such as soul loss 4, 5. This process not only relies on the action of the shaman themselves, but also through the participation of everyone present, including the patient 4, 5. This exemplifies the dynamic relationship between the authority of the religious healer, the participants and the social embodiment of values as key in making sense of the process of healing.

Tony Robbins seems to define health as a unity between how one lives their life and the cultivation of the power of their inner-self to create fulfilment and wellbeing. For example, in a video Robbins guides Rechaud, a 30-year-old man with a stutter, through a ritualized process of searching through memories for a cause of the stutter and bringing out Rechaud’s ‘inner warrior’ 13. Rechaud emerges ‘healed’ from his stutter and delivers a speech at one of Robbins seminars, acting as a symbol of success for this method of healing, which generated intense emotional responses from the crowd 13.

As with the Shamanic trances, Robbins guides Rechaud through a ritualized process of self-narrative that taps into imagery embedded in memories and in the symbol of the self as a ‘warrior’, to transform Rechaud and unify his inner self with his physical body to overcome the stutter.

Conclusion:

Motivational speakers in Anglo-American nations are not unlike shamans in a variety of other cultural settings – they are a culturally sanctioned form of (non-biomedical) healer, with accepted social authority. In observing Tony Robbins’ techniques, we can see how he uses this authority to lead audiences through rituals that facilitate a shift in self. His motivational seminars become a liminal space in which people are taken through a process of re-making their own narratives according to the framework he lays out, and thus are able to heal body, mind, and ‘self’.

References

- Bielo, J. S. (2015), ‘Who do you trust?”, Anthropology of Religion: The Basics, London: Routledge, 106-134

- BigMindSuccess (2017), ‘TONY ROBBINS 2016/2017 Change Your Life’, available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3jmTuzPEXTY [accessed 4th Sept 2018]

- Csordas, J. J. (1990), ‘Embodiment as a Paradigm for Anthropology ’, American Anthropological Association, 18(1), 5-47, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/640395.

- Desjarlais, R.R. (1992), ‘Yolmo Aesthetics of Bode, Health and ‘Soul Loss’’, Department of Social Medicine, 34(10), 1105-1117

- Desjarlais, R.R. (1992) ‘Chapter 1: Imaginary Gardens with Real Toads’, Body and Emotion: The Aesthetics of Illness and Healing in the Nepal Himalayas. University of Pensylvannia Press, 3–35.

- Dunn, C. D. (2017), ‘Personal Narratives and Self-Transformation in Postindustrial Societies’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 46, 65-80, available: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116- 041702

- Gabuna, R. (2017), ‘The world’s top 50 most popular motivational speakers’, available: speakerhub.com

- Gilbert, M. (2002), ‘Why the motivation business is booming’, Ebony, 58(2), 134-136, available: books.google.co.nz/books

- Guillebeau, C. (2010), ‘How to Be a Motivational Speaker’, available: www.psychologytoday.com

- Idler, E. L. (1995), ‘Religion, Health, and Nonphysical Senses of Self ’, Social Forces, 74(2), 683-704, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2580497

- Lambek, M. (2014), ‘What is “Religion” for Anthropology? And What Has Anthropology Brought t Relgion?’, in Boddy, J & Lambek, M. eds., Companion to the Anthropology of Religion, Somerset: Wiley, 1-3

- Oxford University Press (2018), ‘Motivational Speaking’, available: en.oxforddictionaries.com

- RobinHood (2013), ‘Tony Robbins – 30 years of stuttering cured in 7 minutes!’, available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3eOJaprDCDA [accessed 4th Sept 2018

- Robbins Research International, INC. (2018), ‘About Tony Robbins’, available: https://www.tonyrobbins.com/biography/

- Sandmaier, M. (2017), ‘The Tony Robbins Experience’, Psychotherapy Networker, 41(6), 42-46, 58-59, available: https://search.proquest.com/docview/2075729169?accountid=14700

- Synnott, A. (1992), ‘Tomb, Temple, Machine and Self: The Social Construction of the Body’, The British Journal of Sociology, 43(1), 79-110, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/591202 .

- Sökefeld , M. (1999), ‘Debating Self, Identity, and Culture in Anthropology ’, Current Anthropolgy, 40(4), 417-448, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/200042

- Turner, V. (1969). ‘Liminality and Communitas’ (Abridged) in Michael Lambek (ed.) A Reader in the Anthropology of Religion. (2008)

- Sidkey, H. (2010), ‘Perspectives on Differentiating Shamans from other Ritual Intercessors’, Asian Ethnology, 69(2), 213-240, available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40961324

Vaccination debates and the pain of dividuality

**Post originally published on Corpus: conversations about medicine and life, August 7, 2017; with thanks to Sue Wootton for editing and for permission to republish**

Dividuality: “the close proximity and unexpected pull of others in one’s life” (Garish Daswani 2011).

My ears are full of screaming: the name-calling, the CAPS, the exclamation points!!! Whenever vaccination comes up online, and comments are enabled, the conversation quickly devolves into an extremity of outrage and vitriol that reads to me like ‘moral panic.’

My ears are full of screaming: the name-calling, the CAPS, the exclamation points!!! Whenever vaccination comes up online, and comments are enabled, the conversation quickly devolves into an extremity of outrage and vitriol that reads to me like ‘moral panic.’

Coined in the late 1960s, the term ‘moral panic’ makes no judgement on the value of the issues under discussion. Rather, it highlights the social processes in the associated public discourse: the way that story, meaning, and affect coalesce around a particular social problem. Untangling an objective sense of risk from this is nigh on impossible. Besides, people are doing stupid, risky, and harmful things to each other, directly and indirectly, all day long, and in every part of the world. The question becomes not what to think of anti-vaxers, but why the panic about this particular issue, why here, and why now? I believe the answer is not purely medical, but also social and moral.

In matters of morality the contemporary Western world cries ‘choice’ until the word is nearly meaningless. Liberalism snuggles up next to secularism. We fiercely defend our (and others’) rights to make personal decisions, based on personal beliefs. What the issue of vaccination makes horribly clear is the reality is that you can make your personal decisions, based on your personal beliefs, and they can still kill my child. There are limits to our liberalism. Is this the sore spot that the vaccination debate is poking its sordid fingers at? That the personal is social, always.

Arthur Kleinman – psychiatrist, clinician, social anthropologist – discusses morality by looking at “what matters most” or “what is at stake”. In matters of health this includes relationships, personal values and identity. What produces such heat in the debate about vaccine-preventable diseases is that it’s not only individual biographical identities that are threatened, but deeper cultural constructions of the ‘self.’ What the debate specifically grates on is our sense of ourselves as individuals: our clung-to Western vision of the autonomous, bounded, individual self. Silos. Self-governed islands.

Arthur Kleinman – psychiatrist, clinician, social anthropologist – discusses morality by looking at “what matters most” or “what is at stake”. In matters of health this includes relationships, personal values and identity. What produces such heat in the debate about vaccine-preventable diseases is that it’s not only individual biographical identities that are threatened, but deeper cultural constructions of the ‘self.’ What the debate specifically grates on is our sense of ourselves as individuals: our clung-to Western vision of the autonomous, bounded, individual self. Silos. Self-governed islands.

Social anthropologists have compared the different notions of selfhood and personhood that emerge in diverse cultural settings. In many African communities, for example, ethnographic data paints a picture of the self as partible (capable of being divided), and porous (to both physical and spiritual substances) – not ‘individual’, but (according to ethnographers like Girish Daswani) ‘dividual’. This is quite a contrast to the ‘buffered self’ that is a feature of the Western secular age, where the ideal of healthy interpersonal relationships involves having strong interpersonal boundaries.

The vaccination debate invokes a sense of contamination and threat from other human beings. But bodies are never just bodies. They are the site of densely-packed social meanings, and the inspiration for the most accessible and powerful metaphors for pressing existential concerns. Thus the vaccination debate is not only expressive of anxieties about our biological health, but also about our social existence. As each image of an ailing child looms large on our screens, how outrageous it seems to have to acknowledge ourselves as herd animals in this way – how sickening and scary that what matters most to us is at the mercy of those around us. How intolerable. How basically, inescapably, human.

Dividuality cannot just be the folk theory of some cultures… it is the basic reality of all communities. There is an Irish proverb I have always liked:

“In the shadow of each other we must build our lives.”

Though bleak, to me its comfort is in the embrace of that inevitable entanglement with other selves. You will shadow me, just as I will shadow me. I can no sooner extract my life from the influence of others’ dreams, decisions, and faults than I can remove myself from the biological systems of immunity and disease. A relinquishing of the singular pronoun is needed: I, we, are in so many ways collective.

Robyn Maree Pickens’ beautiful essay on bees (published in Turbine/Kapohau 2016) evokes something of this; the sense of ecological interconnectedness which must be cultivated against alarm bells. She concludes by beseeching us to attend to the “nested lives of others.”

Robyn Maree Pickens’ beautiful essay on bees (published in Turbine/Kapohau 2016) evokes something of this; the sense of ecological interconnectedness which must be cultivated against alarm bells. She concludes by beseeching us to attend to the “nested lives of others.”

The air of panic that hovers over the vaccination debate reflects the existential nature of the concerns being expressed: concerns over the threat of vaccine-preventable diseases to the physical wellbeing of our children; threats also to our clung-to visions of ourselves as bounded individuals. We struggle in the grip of an impossible longing for both freedom to make our decisions and freedom from the effects of others’ decisions. Yet this is the shadow-dance we live in. Confronted with a perfect biological metonym for this crumbling dream of moral autonomy, it seems we can do nothing but scream.

Written by: Dr. Susan Wardell

References:

- Cohen, S. (2002). Folk devils and moral panics.

- Daswani, Girish. “(In-)Dividual Pentecostals in Ghana.” Journal of Religion in Africa41, no. 3 (2011): 256–79.

- Kleinman, Arthur. “Caregiving as Moral Experience.” The Lancet 380, no. 9853 (November 9, 2012): 1550–51. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61870-4.

- Pickens, R. M. (2016). We ask so much of them

Red flag waving: Medical crowdfunding trends show the precarity of kiwis in Australia is not just a Covid-19 issue

Posted on by smisu13p

Covid-19 has put an enormous strain on New Zealanders living in Australia, with the Australian government being slow to extend any sort of benefit when lockdowns began in March this year. But the precarity of this group is far from new.

New research on health crowdfunding highlights how wrong things can go, with dozens of families findings themselves reliant on the whims of ‘the crowd’ to support them through dire medical situations, when the state refuses to take responsibility.

Life, death, and the crowd

Donation-based online crowdfunding is an increasingly common way for individuals and families to seek help for various types of need. Health-related crowdfunding is the largest sector of the international platform GoFundMe (which has 80% of the global market share, and takes a tidy percent of all donations) as well as having a major presence on New Zealand’s own non-profit platform Givealittle.

New Marsden-funded research led by Dr Susan Wardell, at the University of Otago, has analysed 574 active campaigns by kiwis both within NZ and overseas, across both platforms, in order to understand who is turning to this means of support, and why. The study found a subset of 44 campaigns were created by Kiwis living in Australia.

Internationally, higher rates of crowdfunding appear in places with weaker formal safety nets; including healthcare coverage, insurance, or social security. Because of this, research into crowdfunding can reveal wider structural inequalities, and in this case the life-or-death implications of questions around benefit eligibility, and citizenship rights, for those who look for a ‘better life’ in Australia.

A better life

The stories and outcomes of the health crowdfunding campaigns in this study, were documented in June 2020 – at the end of New Zealand’s lockdown, but amidst Australia’s ongoing regional restrictions. However, most campaigns pre-dated the pandemic; which is telling in itself

72% of the donation recipients were adults and 28% were children. These are people who experiencing brain tumours, various cancers, heart disease, spinal injuries, spinal injuries, among other issues. The overwhelming majority (77%) were fundraising due to illness, with a handful fundraising due to injuries (9%) or disabilities (7%), and the remaining few campaigns categorised as elective, fertility-related, or mental illness-related. Most campaigns are organised by family members, partners, or friends, rather than the ill person themselves.

Most asked for money to cover direct medical costs, such as hospital care, outpatient medical and diagnostic services, pharmaceuticals, medical or mobility equipment, rehabilitative care and so on.

However, 34% of them also specified the need for help in meeting general living costs, such as household bills, childcare, and transport during times of illness; factors that all have flow on affects for physical health as well. This was much higher than the number of New Zealanders based in New Zealand, who were also crowdfunding, with less than 24% of these requesting help with general living costs.

The lack of access to healthcare and social support, was explicitly stated in two thirds of the campaigns, as the reason for their need:

Multiple cases mentioned working and paying taxes in Australia long term and still not being able to access meaningful supports. For example, while one family had “lived and worked” in Australia for eight years, they were unable to access any social welfare when the father was diagnosed with a brain tumour. Another campaign tells the story of a terminally ill man residing in Australia for 18 years but still has no access to support. In the campaign his family states he is not “allowed” to become a citizen now because of his diagnosis, but also that is unable to return to New Zealand for treatment because supports are no longer available to him after living in Australia for such a long time.

Citizenship struggles

In 2001 policy changes implemented in Australia saw that New Zealanders living there would stay on an indefinite visa, rather than gaining citizenship. While New Zealanders have access to emergency care under this system, any long term and ongoing treatments are not covered. This includes doctors visit and pharmaceuticals. It also limits access to welfare and social support.

Furthermore, marriage to an Australian citizen does not grant citizenship and the subsequent benefits of affordable healthcare and social support. Those married to Australian citizens still were unable to access welfare and health care assistance, while living in Australia with their partner (even if they were working themselves). This means that individuals are faced with potentially uplifting their lives back to New Zealand to receive the treatment needed, even though their lives are embedded in Australia.

Children and families

Though crowdfunding presents individual stories, designed for public attention, very few are about individuals alone. Family members are more than not implicated in the difficult sets of laws around citizenship and welfare access.

Children born in Australia to New Zealand citizens must reside in Australia for 10 years before they are citizens. This means they are ineligible for supports. For kiwi families living and working in Australia, whose young children have medical needs, this rule can have severe impacts. For example, one campaign was for an 18month old child with a serious neuromuscular disorder, who was born in Australia, to parents who are New Zealand citizens. Though he is eligible for “life-saving treatment” through the government, they explain he needs further help for costs he is not eligible for help with, including the therapies, and equipment, that might enable him to one day crawl or walk.

Crowdfunding campaigns typically involve narratives crafted to present ‘deserving’ individuals as worthy recipients of donations. Overseas studies have shown this typically takes the attention away from systemic issues. The campaigns we studied were atypical in that, to explain their situation and justify asking for help, they often went into detail about the systems they were caught within:

Both these examples reflect the fact that if parents of a child are New Zealand citizens, even if the child was born in Australia, they still do not have access to supports and affordable healthcare for that child. This is in stark contrast to what Australians living in New Zealand receive. It shows the high degree of awareness of the campaigners to the systems they are caught within, but have no opportunity to change or contest.

Unequal exchange

The benefits extended to New Zealanders living in Australia are vastly less than those that apply to Australians living in New Zealand. This has been the focus of an ongoing campaign by Oz Kiwi, a small team of volunteers governed by a committee, whose purpose is “campaigning for the fair treatment of New Zealanders living in Australia”. They provide the following, striking graph about the disparities…

Figure 1: ‘Rights comparison’, from the OzKiwi fact sheet, October 2016. http://www.ozkiwi2001.org/2016/05/oz-kiwi-factsheet/

In 2017, in response to census data researchers also pointed to inequality and discrimination against New Zealanders living in Australia. They also suggested that these measures appear to be specifically targeting Māori and Pasifika immigrants, with less than 3% of immigrants from New Zealand who take up citizenship being Māori. OzKiwi also suggestion that single mothers are disproportionately affected by this process.

Covid19 has brought the inequalities to media attention in new ways. In March New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern had to publicly and repeatedly request that the Australian Government provide supports for the Kiwis stuck in Australia during the pandemic – and struggling with job losses, and subsequent loss of incomes – in the same way that New Zealand was providing care for Australian citizens stuck in New Zealand. The eligibility of Kiwis for the Australian ‘Jobkeeper’ benefit scheme was eventually agreed. But with the scheme expiring several weeks ago, it is a better time than ever to recognise that the problem is bigger and deeper than this.

Red flag waving

Data on crowdfunding from both before and during Covid19 confirms that kiwis who seek financial assistance from online publics, while living in Australia, are overwhelmingly doing so because they have limited access to formal social supports.

Is it right that they should have to do so?

Crowdfunding is ultimately an unreliable form of meeting what are sometimes life-or-death needs – shown in much existing data to fail to reach its financial goals more often than not. It is a gap-stop at best, and at worst, a red flag waving from the ditch people have fallen into, between Australia and New Zealand, and the safety nets designed not to catch them.

Posted in Case study, Media/political commentary | Tagged australia, benefits, citizenship, Covid-19, Covid19, crowdfunding, health, health crowdfunding, medical anthropology, medical care, medical crowdfunding, migration, New Zealand, precarity, Social anthropology, social security, welfare | Leave a reply