A couple of days ago my five year old niece asked me if it was winter – an easy mistake to make in the unsettled early weeks of Dunedin summer. When I corrected her, she replied confidently, “but it’s going to snow at Christmas – it always snows at Christmas!”

It’s not surprising that children in this part of the world might get confused about the impending arrival of the snowy scenes that surround us at this time of year. But what may be surprising to learn, is that the transfer of Christmas traditions from the old world to the new was a slow and uneven process. As Dr Ali Clarke pointed out in her recent Global Dunedin lecture, religious festivals provide a window into cultural encounters in New Zealand – not just between British settlers and tangata whenua, but amongst the new settlers too. Dunedin, with its mixed population of Scots and English, is an excellent location to note the marked difference in their observance of Christmas.

This reflected changes after the Reformation in England, when Protestants trimmed festivals. The Anglican calendar centred on events in the life of Jesus, while Presbyterians did away with all festivals, focusing instead on the week and the significance of the Sabbath. So in England, Christmas was an important holiday; while in Scotland, it was an ordinary working day. The Scots shifted their main celebrations to New Year, which was not a holiday in England.

In early Dunedin, the large number of Scots arriving from 1848 continued this tradition of working on Christmas Day. In the town, Anglican influence was soon felt, however, and it became a business holiday. But farmers of Scottish origin continued to ignore Christmas until the turn of the century. As the Scots did begin to embrace this celebration, it was more about food and family than religion. Throughout the colony, new traditions developed to celebrate a summer yuletide. Strawberries and cream joined Christmas pudding as a favourite dessert, and harvesting home grown vegetables (such as potatoes and peas) in time for the big day became an important part of festive preparations.

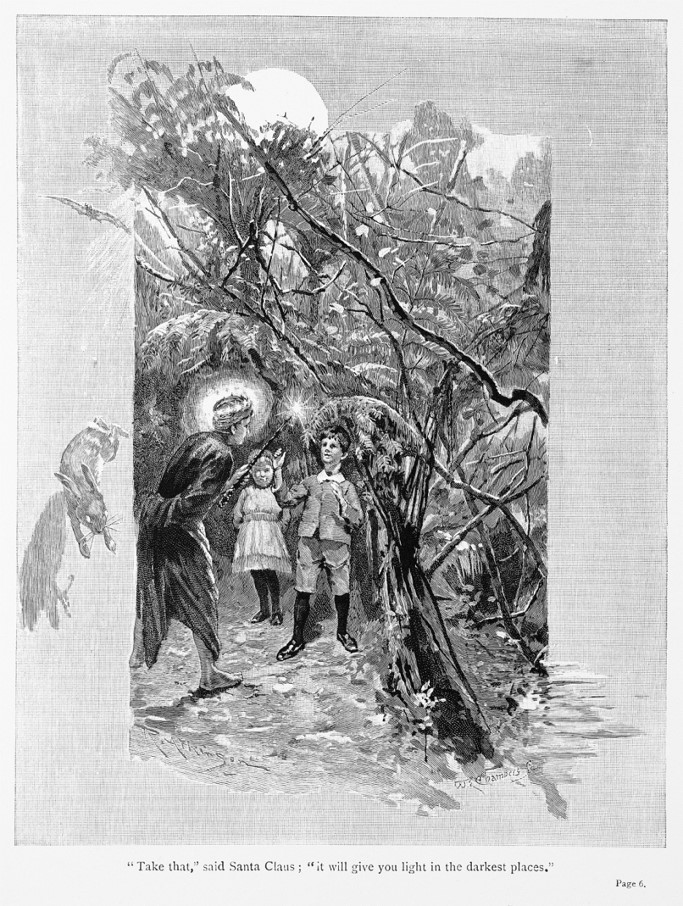

“Take that”, said Santa Claus; “it will give you light in the darkest places.”

Kate McCosh Clark, A Southern Cross Fairytale, 1891.

Source: http://www.childrenslibrary.org/

But what about the children? Did Santa’s sleigh jingle all the way to New Zealand? In 1891, Kate McCosh Clark, a former resident of Auckland then living in Britain, wrote A Southern Cross Fairy Tale. The story was for colonial children, “to whom snow at Christmas is unknown”, as well as youngsters in the “older land” who wanted to know what Christmas was like for their kin on the other side of the world. McCosh Clark set the scene with poetic descriptions of the local environment:

“It’s Christmas Eve and the long soft shadows of a summer night are quickly falling… No sound of joyous bells is borne upon the air… only the Bell-bird’s chimes from the bush, and the distant cow-bell’s tinkle mid the shadowy Manuka clumps.”

As the story went, the two children of the house were woken by a voice at midnight, exclaiming, “Wake up little ones!” There stood “a lad with a smiling face” and a bag of gifts.

Hal asked, “Are you a fairy?”

“No”, the lad proclaimed, “I am only Santa Claus”.

“Why, I thought Santa Claus was an old man”, said Hal.

“So I am, in the Old World”, replied he, “but here, in the New World, I am young like it.”

Hal, understandably, had immediate concerns about this proposition. Where were the reindeer, and the sleigh? How would his stocking be filled with gifts? In lieu of these traditions, the youthful Santa treated them to an enchanted tour of natural wonders, singing glow worms, gnomes and fairies, tuis and tuataras.

As it turned out, colonial children were to have their exotic new world and be visited by Santa Claus. In Dunedin from the turn of the century, children could visit magic caves and grottos in department stores like DIC, and in the arrival of Santa we might see the origins of the Santa parade. Direct from the South Pole, Santa emerged from the railway station and made his way through the town.

So when you are visiting Pixie Town, enjoying a Christmas barbeque, or queuing at the market for strawberries – take a moment to reflect on the way that our English, Scottish, and other cultural heritage has affected the way we celebrate (or not!) our mid-summer Christmas. Happy holidays!

Jane McCabe

References

Ali Clarke, Holiday Seasons: Christmas, New Year and Easter in nineteenth century New Zealand. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2007.

“Important Notice”, Evening Star, 17 December 1904, p.6

Kate McCosh Clark, A Southern Cross Fairy Tale, UK, 1891. Accessed at http://www.childrenslibrary.org/

“A Southern Cross Fairy Tale”, Auckland Star, 19 December 1890, p.3

See Ali Clarke’s Toitu lecture at her blog: http://clarkesquill.com/