Hospitals are part of community too

The 274-page full report New Zealand Health and Disability System Review has been recently released (June 16, 2020). While the main headlines refer to the creation of a new overarching entity ‘Health NZ’, a new entity responsible for Māori health and a smaller number of District Health Boards, there are some other interesting and somewhat implicit themes that emerge.

The 274-page full report New Zealand Health and Disability System Review has been recently released (June 16, 2020). While the main headlines refer to the creation of a new overarching entity ‘Health NZ’, a new entity responsible for Māori health and a smaller number of District Health Boards, there are some other interesting and somewhat implicit themes that emerge.

The report heavily, but implicitly, emphasizes a Tiered structure of healthcare. I obviously missed this basic foundational concept somehow, since I was initially unsure exactly what was meant by Tier 1, 2, 3 services. At first, I thought it was just new terminology for primary, secondary, and tertiary care, which admittedly has its problems too, but there seem to be important differences. One recommendation of the report is to move Tier 1 services provided by hospitals out into the community. What would those services be? On page 98, Tier 1 services are defined:

“Tier 1 encompasses a broad range of services and other activities that take place in homes and communities, in marae and in schools, delivering most of the health services that most people need, most of the time. Tier 1 includes, but is not limited to self-care, mental health services, general practice, maternity services, Well Child / Tamariki Ora, outreach services, oral health, community pharmacy services, health coaching, medicines optimisation, district nursing, aged residential care, hauora Māori services, community paramedic services, school based services, home-based care and support, rehabilitation and palliative care. It also includes laboratory and radiology services and other allied health care that takes place outside of hospital, such as podiatry, physiotherapy and dietetics. Most kaupapa Māori services are in Tier 1.”

Note that rehabilitation and palliative care are counted as Tier 1 services. What does ‘moving out into the community’ mean for rehabilitation services? The report refers to services provided in homes, marae, and in schools – presumably also workplaces, sports fields, churches, and shopping malls. But obviously not hospitals since somehow hospitals are not part of the community. Although some rehabilitation services already do operate out in the community many others do not and could not successfully transition to such locations. Some rehabilitation services have evolved to work best as inpatient facilities because of the efficiencies of specialist staff, better client outcomes and access to multiple health professionals in a timely and organised way. Spinal cord injury is an obvious example, but stroke units are also examples of where concentrated expertise has been clearly shown to work better than distributed generalism. Having said this, the Review is a little ambiguous with regards to rehabilitation services since they do not appear in the list of Tier 1 services in Table 7.1.

I wonder whether it would not make more sense to bring the community into the hospitals. Why should hospitals be some kind of space apart? There is a strong unspoken sense that hospital structures mainly benefit the people that live close by i.e. in cities or provincial centres, to the relative disadvantage of rural and remote communities; but this tends to ignore the valuable contribution that smaller community rural hospitals have made but which have been progressively pared back because of efficiency concerns.

This separation of ‘community’ from ‘hospital’ is an interesting phenomenon; what is the underlying basis for excluding hospitals from their communities? An immediate thought is this need for efficiency – that it is somehow cheaper to provide similar services in different settings. Often, that just means cost-shifting to the consumer. Instead of obtaining free care from hospital-based specialist clinics, consumers get that care from general practices or other providers trying to run a business, for which there is a significant direct cost. But there probably are other more ideological reasons too. Hospitals are traditionally places where overnight healthcare is provided, that is, patients are ‘admitted’, which means staying in for 1 or more nights to receive 24-hour care that cannot be easily provided in the patients’ home. But they became monolithic institutions that de-personalised and disempowered the people they were meant to serve. The shift from hospitals to community can be seen as part of the same process that characterised the de-institutionalisation of mental health hospitals and care-homes for people with disabilities, especially intellectual disabilities.

But hospitals are not places where people/patients actually live, in contrast to the mental hospitals and care-homes of the past. And they no longer provide solely overnight care either. Space for outpatient clinics is probably the resource of shortest supply in many hospitals. Ambulatory care is a major function of hospitals, not just overnight care. People using these services are still in their community. It is misleading to consider that a hospital-based emergency department is fundamentally different from an accident and medical after-hours clinic. More severe accidents are managed at a hospital ED, but this is a difference of degree rather than substance. There is no intrinsic reason that I can see for not allowing more community-oriented services into hospitals. Let’s make hospitals feel more part of their community!

Occupational performance coaching in Hong Kong

RTRU Senior Lecturer, Dr Fiona Graham, work on Occupational Performance Coaching (OPC; a parent-coaching intervention) has lead to a new collaborative research partnership with clinical researchers in Hong Kong. Recently this group was awarded a grant by the Research Fund Secretariat from Food and Health Bureau, under the Health Care Promotion Scheme in Hong Kong in order to study “A parent-coaching intervention to promote community participation of young children with developmental disability.” This project will be lead by Dr Chi-Wen (Will) Chien with input from Dr Graham and co-investigators Dr Yuen-yi (Cynthia) Lai and Dr Chung-Ying Lin.

Participation in community activities is important for children to learn skills, make friends, and have fun. Children with a disability and their families, however, are reported to participate less in the activities in their communities. This project will examine the cultural appropriateness of OPC when used in Hong Kong and its effectiveness to enable community participation of young children with developmental disability. The effect of OPC on child well-being will also be examined as an important mediator of children’s participation. A randomised control trial (aim to recruit over 75 children) will be conducted in Hong Kong. Parents in the experimental group will receive OPC. Parents in the control group will receive information about community resources by phone. Findings will provide important information about the effectiveness and cultural appropriateness of OPC for Hong Kong citizens and will inform future service design for children and families in Hong Kong.

The (Un)expected Benefits of Studying Rehabilitation

The (un)expected benefits of studying rehabilitation

Spending the last few days preparing for teaching the REHB701 Rehabilitation Principles paper for 2019 has been fun! I took this course in 2010 and it had a huge impact on the way I practiced as a physiotherapist and in my future career (now mainly in the area of teaching and clinical research).

Rehabilitation studies, with a focus on understanding how best to support a person experiencing disability to live well so that they are able to meaningfully participate in valued life activities and roles, resonated with me. I had worked as a physiotherapist for 20 years, alongside people with acquired brain injuries – so I understood the need to think beyond what we deliver, to also consider how we deliver. The way I related to people was important. The role I took within that relationship was important. How well I was able to listen to their priorities and concerns was important. My ability to work interprofessionally was important. I may have had the best technical skills in the world, but if I didn’t use relational practices that respected and utilised the strengths of the person I was working alongside, then the outcomes would be less than optimal and the process less than empowering for the person undergoing rehabilitation. Within REHB701 I was able to draw on my clinical experiences, developing theoretical ‘coat hangers’ from which to hang the various ideas. I developed a language to articulate the key rehabilitation concepts, allowing me to communicate more effectively with both patients and rehabilitation team members. The bonus bit was that I was also re-energised within my work role!

And I loved the learning…. Studying with people from a range of clinical backgrounds was eye-opening and encouraging. Gaining confidence with reading research papers. Improving my written skills. Building my confidence when contributing to complex issue discussions. But most of all, starting to pay more attention to the experiences of people who are undergoing rehabilitation. Listening to their voices. Hearing their stories. Starting to understand their perspectives – and then critically reflecting on my own practice, as well as the structure of rehabilitation services, in the light of these new insights.

So, consider starting your own studies in rehabilitation. Just like I did in 2010, consider the possibility of ‘dabbling’ a bit. Put a toe in the water. Explore the possibilities. And you never know – you might end up ‘going deep’!

-Rachelle Martin

Exciting new NZ-Japan research collaboration

RTRU has recently received a new funding grant from the Royal Society Te Apārangi to support a brand new research collaboration between occupational therapy researchers from Japan and Māori, Pacific, and Pākehā researchers in New Zealand. Lead by yours truly (William Levack), this project involves the development and testing of a) an English-language version and b) a Māori/Pacific version of a Japanese iPad application called the “Aid for Decision-Making in Occupational Choice” (ADOC).

ADOC is designed to help health professionals engage with patients (adults and children) and their family/whānau in collaborative goal setting for rehabilitation (e.g. for people with stroke, spinal cord injury, cerebral palsy, or dementia). Despite the importance of goal setting in rehabilitation, past research has demonstrated that involving patients in goal setting can be difficult, with health professionals tending to dominate discussions around the selection of goals, and issues such as communication and cognitive impairments creating obstacles to robust patient involvement. This project will provide the ground work required for future research investigating the use of digital technology as a tool to support rehabilitation professionals to be more culturally responsive and person-centred in their clinical practice – improving the quality of their service delivery and increasing opportunities for more meaningful health outcomes for their patients.

My research collaborators for this project are Bernadette Jones (Ngāti Apa Ngā Wairiki), Dr Tristram Ingram (Ngāti Kahungunu ki Heretaunga, Ngāti Porou), Dr Dianne Sika-Paotonu, A/Prof Rebecca Grainger (from University of Otago), A/Prof Kounosuke Tomori and Dr Tatsunori Sawade (from Tokyo University of Technology), and A/Prof Kayoko Takahashi (from Kitasato University). Funding from the Royal Society Te Apārangi will support travel between New Zealand and Japan to help us successfully complete this work. Additional funding support for our various collaborative projects over the next two years has also be provided by the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science and by a University of Otago Research Grant.

Report from Atlanta, Georgia – ACRM 2017

I’ve been at the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine (ACRM) Conference in Atlanta, USA, this week. My main reason for going was to promote the work of Cochrane Rehabilitation to our North American colleagues. However, I also had the opportunity of collaborating with a great group of academics and clinicians from the US for a half-day pre-conference workshop on self-management training in rehabilitation. (This group included Veronica T. Rowe, PhD, OTR/L – University of Central Arkansas; Jeanne Langan, PT, PhD – University of Buffalo; Marsha Neville, OT, PhD – Texas Woman’s University; Shelley Dean, OTD, OTR/L – Crossway Pediatric Therapy; Candice Osborne, PhD, MPH, OTR – University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.)

The conference was massive, with over 2000 attendees. However, as many as 29 different conference streams could be running at the same time. As a presenter this meant you could quite easily get lost in the crowd, and end up travelling half way around to the world to speak to just a handful of people. Fortunately, the 75 minute symposium on the work of Cochrane Rehabilitation sparked a bit of interest, and I had a good turnout from an engaged audience – many of whom had extensive experience in systematic reviews and clinical guidelines.

I also had the opportunity to meet with a few key people in ACRM:

- Dr Ron Seel, Evidence and Practice Committee Chair at ACRM

- Prof Marcel Dijkers, Research Professor from Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and lead on a current (massive!) guideline on traumatic brain injury rehabilitation, funded by the Brain Injury Association of America.

- Prof Allen Heinemann, Co-Chief-Editor of Arch Phys Med Rehab

There was a lot of interest in the potential for collaboration between ACRM and Cochrane Rehabilitation. ACRM is already highly involved in systematic review and guidelines work – some of which they externally contract. ACRM has an established relationship with the Campbell Collaboration – which is another excellent, but somewhat newer group than Cochrane, which also publishes systematic reviews but with more of a focus on the social sciences. The main objective for both ACRM and Cochrane Rehabilitation at this stage is to find out about what each group is working on, so that can we work in synergy and avoid unnecessary duplication of activities. Incidentally, much of the guideline work in America ends up in their National Guidelines Clearinghouse, which is a good resource to search when looking for such material. Going forward, Cochrane Rehabilitation and the Evidence and Practice Committee of ACRM are aiming to maintain closer communications about events and activities that we get involved in. Some initial discussion was held about possibly running a collaborative symposium at the ACRM conference in Chicago, 2019.

There was a lot of interest in the potential for collaboration between ACRM and Cochrane Rehabilitation. ACRM is already highly involved in systematic review and guidelines work – some of which they externally contract. ACRM has an established relationship with the Campbell Collaboration – which is another excellent, but somewhat newer group than Cochrane, which also publishes systematic reviews but with more of a focus on the social sciences. The main objective for both ACRM and Cochrane Rehabilitation at this stage is to find out about what each group is working on, so that can we work in synergy and avoid unnecessary duplication of activities. Incidentally, much of the guideline work in America ends up in their National Guidelines Clearinghouse, which is a good resource to search when looking for such material. Going forward, Cochrane Rehabilitation and the Evidence and Practice Committee of ACRM are aiming to maintain closer communications about events and activities that we get involved in. Some initial discussion was held about possibly running a collaborative symposium at the ACRM conference in Chicago, 2019.

I also attended a great series of presentations by Tessa Hart, John Whyte, and colleagues about the Rehabilitation Treatment Taxomony, which has now been renamed the Rehabilitation Treatment Specification System (RTSS). I had wondered about the possibility of using this taxonomy in the context of my work with Cochrane Rehabilitation – attempting to identify and classify all rehabilitation-relevant Cochrane reviews. However, the taxonomy is not quite at the stage where it is actually a classification system yet. Hart, Whyte and colleagues have completed some really interesting work to develop a framework for such a taxonomy in the future, but have yet to operationalise this framework into standardised classification system. Nonetheless, the RTSS already has some direct application to treatment description, and a lot to offer in terms of teaching clinical reasoning in the context of rehabilitation – something that I would be interested into introducing into our teaching material at RTRU.

My slides from the Cochrane Rehabilitation symposium: ACRM 2017 – Cochrane Rehab Symposium Slides

Med Info 2017 and AMEE conference report

I am writing this at Heathrow airport, en route back to New Zealand after attending two conferences. Neither of the conferences were rehabilitation related however both were relevant to the activities of the RTRU. My musings follow:

The first conference was the 16th World Congress of Medical and Health Informatics, also known as Med Info 2017, held in Hangzhou in China. About 2000 hard core “Health Informaticians” from 6 of the 7 continents were in attendance. Health Informatics is a multidisciplinary field which uses information technology to improve health care. I met people from every health profession, economists, policy makers and hard core information technologists, all united by an interest in applying rigor to the use of health information and communication technologies in health care to improve health and wellbeing.

The most rehabilitation relevant session I attended was a workshop called The Two-sided Market Perspective of e-Health where the concept being discussed boiled down to Uber for health services: the idea that an electronic platform, that acted as a neutral transactional space, could allow people with health needs to be match up with, and purchase health services. This is a relatively new concept, although I notice one of the workshop facilitators has already edited a book on the subject! The vigorous discussion highlighted the challenges of “users” not always having sufficient knowledge of services and treatments to be able to judge which “service” is the best fit for them for currently and future health outcomes, the challenges of user rating systems for services (sometimes the medicine tastes bad) and how will payers feel about allowing users/clients/patients to choose their own services in a market place. A similar system, although not digital, being developed for people in New Zealand through “Enabling good lives” where people with disabilities and their whanau identify their goals, the support they require to meet them and then services are matched to enable to them to reach these goals. I also wondered if ACC, currently going through a digital transformation, might provide an online directory of services providers for ACC clients to match with. We are likely to see significant digital overhaul of health in New Zealand in the next ten years so not beyond possibilities.

While in Hangzhou I was also lucky enough to visit the famous WestLake

and visit a Tea Village where the famous and supposedly health-giving Dragon’s Wells tea is grown.

My next conference was the Association of Medical Educators of Europe (AMEE) conference in Helsinki. A larger conference at 3700 attendees was a deep dive into Health professionals education. There was a lot of discussion of Programmatic Alignment, the concept that all aspects of the curriculum from learning outcomes, methods of teaching and learning and assessment should be congruent. So if the learning outcome is to be a “critical consumer of rehabilitation evidence base” the teaching and learning should include practice of critical appraisal and the assessment should require demonstrate of this skill. I will be reflecting this back to RTRU to prompt reflection that we are achieving this in our taught papers. I was also introduced to the curious concept of “Threshold concepts” which are an idea that, once grasped, changes the way learners think about themselves. The concept cannot be forgotten and may be emotionally difficult. An example might be the myth of black/white answers in medicine. These are the “ah-ha” moments in our learning as health professionals. I am still processing this idea but already can recognise a few in my own journey – have you had any? Also I am pondering what are the Threshold concepts in our understanding of rehabilitation. Any ideas are welcome.

While there, I had the chance to visit a bit of Helsinki and I was surprised to find an amazing berry market.

I’ve also eaten reindeer stew and elk meatballs, neither of which I think I need to do again!

I am returning home refreshed and intellectually invigorated. Now, off to that 12 hour flight…

Rebecca G.

REHB706 students on their site visit

Residential seminar time! Our REHB 706 Work Rehabilitation students, many of them experienced Vocational Rehabilitation Service or Ministry of Social Development staff, get to meet in person at the Waste Management toxic waste site for the first time. They have all been busy interacting on the Forum since the semester started, so all know each other well, despite being a big group. As you can see we have been very lucky with the weather!

Experiences of younger adults with neurological conditions living in nursing homes

Whoo p! Kerry Thornton and I have just published a new paper about the experiences of working-aged adults living in institutional residential care settings intended for much older people. This qualitative metasynthesis arose from some work that Kerry did with me as a mini-research project towards her MHealSc(Rehabilitation). This review was challenging to conduct because of the paucity of research in this area of study, and because of the diversity of social, economic and organisational contexts of institutional living arrangements worldwide. We used ‘sensitivity analysis’ to endeavor to be as inclusive as possible with the data that we incorporated into the qualitative metasynthesis, while concurrently avoiding placing too much weight on less directly relevant or poorly conducted studies. The full paper is available from the British Journal of Occupational Therapy website, where it is currently listed as an ‘early online’ publication: click here to link to the paper itself. The paper is a pay-per-view publication – so email me if you can’t access a copy of it but would like to know more.

p! Kerry Thornton and I have just published a new paper about the experiences of working-aged adults living in institutional residential care settings intended for much older people. This qualitative metasynthesis arose from some work that Kerry did with me as a mini-research project towards her MHealSc(Rehabilitation). This review was challenging to conduct because of the paucity of research in this area of study, and because of the diversity of social, economic and organisational contexts of institutional living arrangements worldwide. We used ‘sensitivity analysis’ to endeavor to be as inclusive as possible with the data that we incorporated into the qualitative metasynthesis, while concurrently avoiding placing too much weight on less directly relevant or poorly conducted studies. The full paper is available from the British Journal of Occupational Therapy website, where it is currently listed as an ‘early online’ publication: click here to link to the paper itself. The paper is a pay-per-view publication – so email me if you can’t access a copy of it but would like to know more.

The problem of goal attainment scaling

Goal attainment scaling (GAS) is a popular method for individualized outcome measurement, but it comes with problems that limit its application. This video provides an overview of why GAS appears attractive as an outcome measure, but also presents some seldom discussed criticisms of its application.

Congratulations Dr Emily Thomas PhD!!

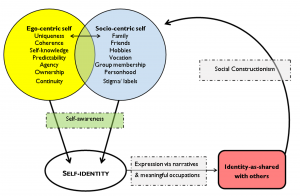

A huge congratulations from RTRU to Dr Emily Thomas who was, just this month, awarded her PhD! Emily’s thesis is entitled “Development of a measure of sense of self following traumatic brain injury” and can be downloaded from the OUR Archive website (click here for a direct link).

In addition to a number of conference presentations, Emily’s thesis has already resulted in one great publication (Thomas et al. 2014) and a book chapter (Thomas et al., 2015). Another outcome from Emily’s thesis has been the finalisation of a new clinical measure: the Brain Injury Sense of Self Scale, which is a interval-level scale that can detect problems with self-identity after brain injury. We are just in the process of setting up a new website to make this measure freely available.

Emily currently works as a rehabilitation consultants for the Solent NHS Trust in Southampton, UK.

References:

1. Thomas EJ, Levack WMM, Taylor WJ. Self-reflective meaning making in troubled times: Change in self-identity after traumatic brain injury. Qualitative Health Research 2014;24(8):1033-47.

2. Thomas EJ, Levack WMM, Taylor WJ. Rehabilitation and recovery of self-identity. In: McPherson KM, Gibson BE, Leplege A, eds. Rethinking Rehabilitation: Theory & Practice. Boca Raton: CRC Press 2015.