“Alan, Alan, Alan, we have a big one”. And sure enough, in front of the kids and me was the brown outline of a bone that hadn’t seen the light of day for millions of years.

It’s big country out here. And baking hot, even this early in the morning. Driving out of Alexandra up the Manuherikia Valley the views are vast, and big, with your eye drawn to the horizon. The sky is that dark blue-black that heralds an impending thunderstorm later in the day. Black clouds stretch in banks across the sky like zebra crossings for the gods. Dotted throughout this brown hill country with its rocky schist tors, are seemingly out-of-place lurid irrigated fields – bright green interlopers in an otherwise dry landscape. The kids and I imagine what this place must have been like when Polynesians arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand with the hillsides covered in kowhai and lancewood forest. The kids can barely contain their excitement about finally being in the field with daddy.

We are on our way to St Bathans, that Miocene wonderland full of fossils from a different world 15-19 million years ago. Back home Maria is enjoying a week to herself and the sewing machine. It’s good to be back here after a short hiatus. We are part of a team that’s here for the next week and includes people from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, the University of Otago, and Massey University.

Turning down the gravel road at St Bathans, any semblance of wind dies away, and the temperature skyrockets. This is one of the driest parts of Central Otago…even the grass has given up trying to grow. Yet today, it’s incredibly humid and sticky (it’ll get to 38 degrees by the end of the day). Loaded up with our excavation gear we walk down the steep sheep track to the creek flat and cross the stream. Our site is in a bank that is being exposed by the periodically flooding creek.

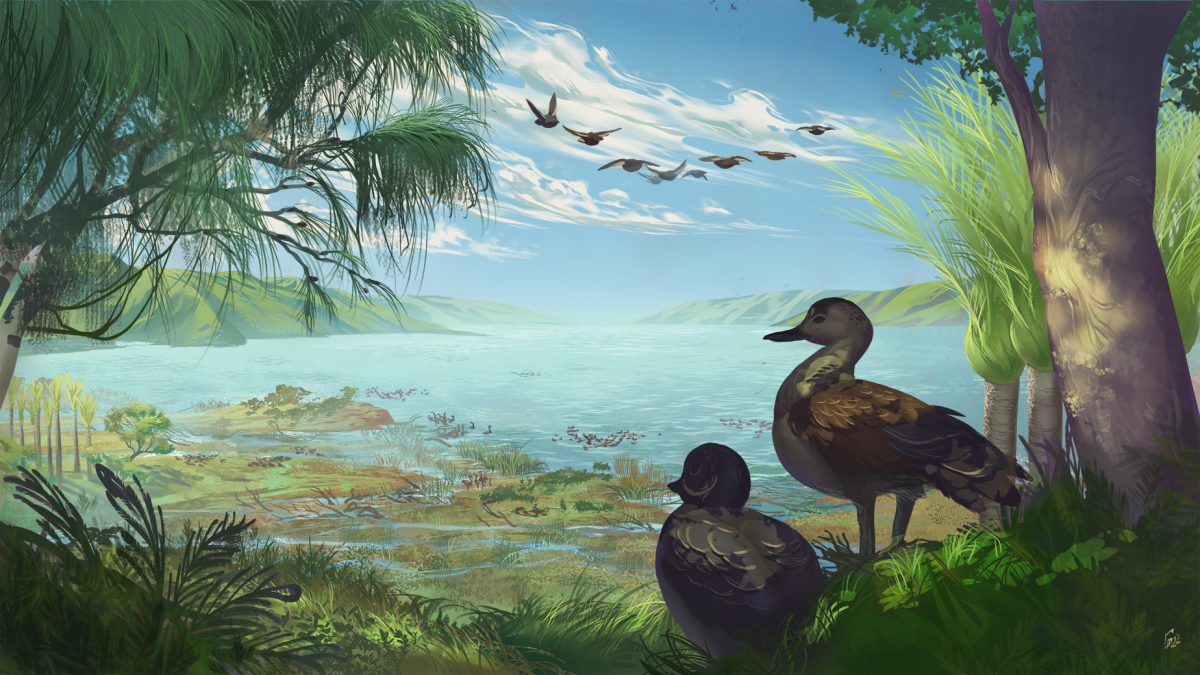

We’d spent the previous day clearing mountains of gravelly overburden to reach the 10 cm deep layer near the bank’s base that contains the treasure trove of fossils bones, brown and black jewels in a sandy blue-green tomb. This whole area used to be the giant Lake Manuherikia that covered what is now Central Otago. As animals died in and around the lake, their bones were covered and preserved for millions of years – until now.

Lying on my stomach, the creek burbles behind us, torturing us with its cool waters, while a cool breeze snakes up the valley, making the long grass sway in the wind. Later in the day, the kids will create a little swimming hole and go on native fish patrol. Will is next to me as I show him how to find fossil bones, while Grant is sitting on my back sorting through lumps of sediment for those tell-tale signs of brown and black gold. Suddenly, the Will and I uncover the knobbly end of a bone. Swapping from my trowel to dental picks we slowly start removing sediment bit by bit.

I can tell from the bumps on the bone that we are dealing with some sort of duck. Ducks are the most common bird bones at St Bathans, but I wasn’t sure what sort of duck this was from; it was clearly large and chunky. Grant excitedly starts calling “Alan, Alan, Alan” (not Steve). That’s Alan Tennyson from Te Papa, who seems as excited as the kids. Soon the other members of our party are coming over for a gander. We carefully excavate the bone and gingerly wrap it in tissue paper for eventual transport back to Te Papa. With this bone and other discoveries like it, we knew we had something special, something new…we just had to prove it.

St Bathans was home to more kinds of duck than virtually any other fossil site in the world, the largest being a shelduck (called Miotadorna sanctibathansi, the St Bathans shelduck). What was the whakapapa of ours?

Back in the basement of Te Papa, the real work began. Comparing our new material to fossil bones already in the collections, including what would become the holotype (the specimen that owns a taxonomic name and everything else is compared to), our new duck looked a lot like a St Bathans shelduck but its size and proportions were all wrong. It was much bigger than today’s paradise shelduck, being the size of a small goose. Now that’s a big duck! We had enough to support our gut feeling that we had discovered something special.

But what to name our new duck? It had to be something fitting. In the end, we named it Catriona’s shelduck Miotadorna catrionae after my mum, who inspired my love of natural history and sadly lost her battle with ovarian cancer just after the first Covid lockdown. I grew up in Nelson and Golden Bay surrounded by caves full of moa bones. Family holidays always involved various aspects of natural history. Mum loved hearing stories of our outdoor adventures, wanting full reports on what we had found. This trip would have been no different.

It’s the end of a long hot day in the field. If anything, the humidity has increased. The kids have had a blast and have become key members of the team, the spitting image of palaeontologists after a hard day in the field. As we make our way through the swaying long grass, half the height of the kids, I’m reminded that the velociraptors in Jurassic Park like long grass. The first drops of rain have started to fall…big fat drops that have been building all day. As we drive back down the Manuherikia Valley, the rocky tors around Tiger Hill in the distance are framed by dark and stormy clouds. Sheets of rain travel across the landscape, illuminated by shafts of light poking through the thunder clouds. Before long, the heavens briefly open with the crack of thunder and lightning, as if the gods are testing whether we are worthy to access the St Bathans Miocene tomb.

In the hot summer evening back at base we enjoy a few beers over a BBQ and celebrate our new discovery – another piece of the jigsaw we have put in place. This is paleontology at its best: fun, collaborative, and full of new discoveries. Bring on the next season.

The reconstruction of Catriona’s shelduck at Lake Manuherikia was done by Simone Giovanardi.

This blog was updated on 5th April to clarify the specimens included in this study.