Ask any museum curator if you could destroy the only known bone of a diminutive extinct animal for genetic research, and the answer, once the curator had regained their composure…well, I’ll leave that one to your imagination.

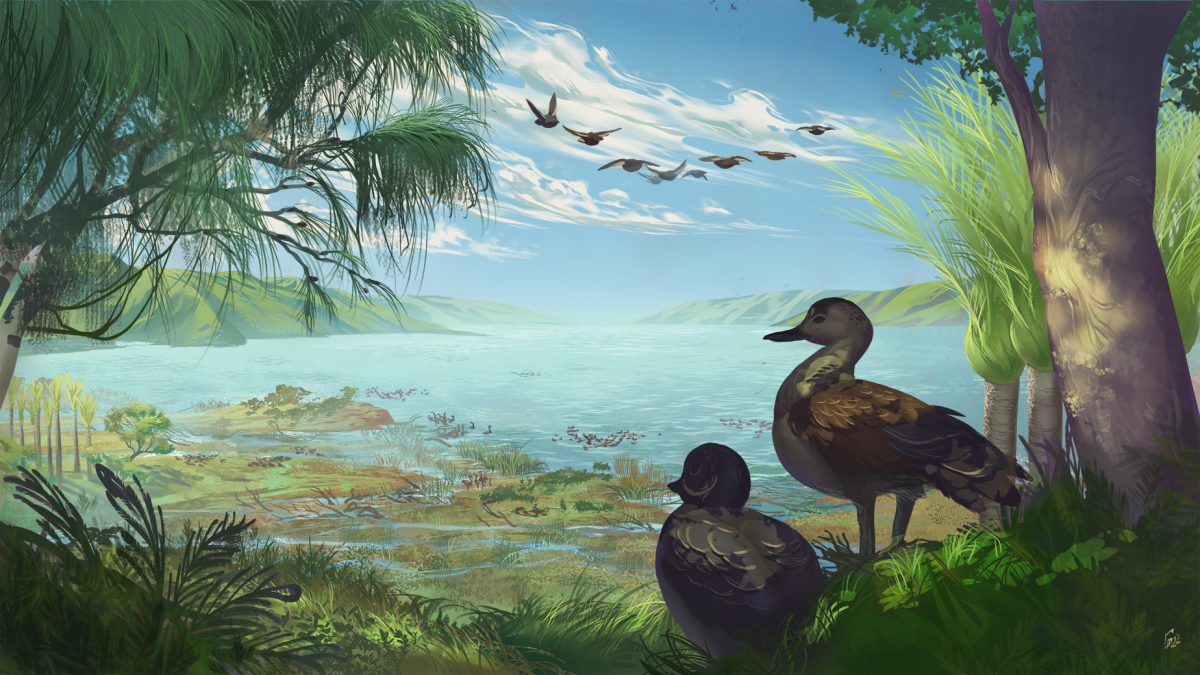

Walk into the behind-the-scenes collection at any museum in Aotearoa New Zealand and you’re immediately drawn to the big things, whether that’s historical taxidermy, like imposing carnivores with their glassy eyes that eerily follow you around the room, or the skeletons of marine leviathans that once explored the ocean’s depths. Yet tucked away, dwarfed by the adjacent shelves upon shelves of carefully curated moa drumsticks, is a single non-descript wax-lined box full of tiny treasures. Hundreds of precious fossil gecko bones from before the arrival of humans, some thousands of years old. Continue reading “From the smallest of bones come the biggest of secrets”