It’s the height of the Central Otago summer – barren, dry and dusty. Driving down the gravel road to St Bathans, we’re travelling back in time, down the rabbit hole to a world long gone. Only ghosts remain of this lost world and that’s what we’ve come here to find. The fossilised bones of a myriad of animals dating back some 16-19 million years from the Miocene period can be found in the sediments of the surrounding area.

Turning off the gravel road and down a farm track, we’re met by the sight of several four-wheel drive vehicles parked up next to a small hill. The “hill” is actually a large, gravel, spoil heap on the banks of the Manuherikia River. This morning, it’s surprisingly quite cool on site, enough that I wish I’d brought a jersey with me. In contrast, some days it can be quite unbearable here, with the sun beating down and with no hope of escape from the heat. The cool waters of the river tease, and you know you can’t go for a swim until the day’s end.

Several metres down in the bottom of a deep broad quarry, I catch up with New Zealand’s Mr Moa, Trevor Worthy. Today, he’s with other key players from Canterbury Museum, (Paul Scofield and Vanesa De Pietri), and Te Papa’s Alan Tennyson, all intent on discovering the secrets of this ancient Wonderland. Their research is currently funded by Vanesa De Pietri’s Marsden Fast Start grant, but this long-running, (18 years and counting), collaborative research programme also includes scientists from the University of New South Wales in Sydney and from the University of Queensland in Brisbane.

Back in the pit, Trevor and Alan are chasing a vein of blue-grey silt containing fossil ghosts that are all that remains of the once diverse St Bathans’ biodiversity. More often than not, they come across a bone that needs to be carefully excavated from its sediment tomb. Once released, the sediment is shovelled into labelled bags, carefully overseen by fellow researcher, Jenny Worthy, and then hauled down to the river.

My pre-schooler is fascinated by fossils and dinosaurs. While there may not be dinosaurs at St Bathans, he is enthralled so helps Paul and Vanesa sieve the bags of sediment. With a little assistance from the river current, my budding palaeontologist releases a jumble of fossil bones that have not seen the light of day in nearly 20 million years. The vast majority of the bones are those of freshwater fish such as the ancient relatives of today’s bullies, galaxids and the extinct New Zealand Grayling. The bones twinkle like black gold in the grey cosmos of silt.

Once in the palaeontology lab, the fossil bones are meticulously sorted from the remaining sediment under a microscope and then compared with reference skeletons to determine what type of animal they belong to. From the literally millions of fish bones now picked through, the team have now identified a few thousand special fossils. These fossil ghosts have revealed truly amazing and somewhat surreal insights into New Zealand’s ancient past. Like Alice in Wonderland, this lost world seems familiar, yet strangely different.

Rather than the barren landscape around St Bathans today, the site was at the centre of Lake Manuherikia, a monstrous lake which measured some 5600 square kilometres. At ten times the size of Lake Taupo today, this palaeo-lake stretched as far as the eye could see, from present day Central Otago to Bannockburn and the Nevis Valley in the west; to Naseby in the east; and from the Waitaki Valley in the north to Ranfurly in the south. Several braided rivers flowed into the lake from a range of distant hills. Animals that died in or around the lake, or were subsequently washed into the waters, were preserved in the silty sediment at the lake bottom.

Far from the hot, dry day the morning is turning into, Lake Manuherikia was part of a subtropical greenhouse world. The surrounding woodland vegetation had a distinctly subtropical Australian flair that included casuarinas, eucalypts, palms, and cycads. My kids and I have found the fossilised remains of these plants around Bannockburn, including sections over a metre thick comprised entirely of palm leaves.

But it was the animal life, not the vegetation that made this Wonderland truly unique. This was a world recovering from the ‘Oligocene drowning’, where up to 80% of our current land area was sent to Davy Jones’ locker only a few million years earlier. Yet, the wildlife that lived in, on, and around Lake Manuherikia was uniquely kiwi, strongly suggesting that some emergent land remained during this near drowning event.

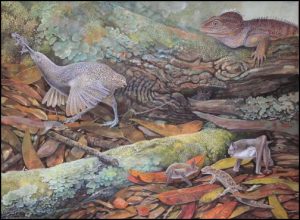

Fish, shellfish and yabbies dominated the aquatic life here. However, New Zealand has always been a land of birds and reptiles, and it was no different here all those millions of years ago. Skinks, geckos, and ancient Gondwanan Leiopelma frogs and tuatara-like reptiles, isolated on this Zealandian ark, lived in the surrounding area. By far the largest reptilian inhabitants were an, as yet undescribed, terrestrial crocodile up to three metres in length, and a large terrestrial turtle. Both originated from evolutionary radiations from Australia and the Pacific; lines that would go extinct later with the arrival of humans.

Birds and bats dominated the skies, along with the probable flying ancestors of today’s kiwi. There were palaelodids, ancient relatives of flamingos and a giant burrowing bat, (another Gondwanan relic), three times the size of today’s relatives, and more closely related to South American bats. Moa, Adzebill and tiny flightless rails, (no bigger than a sparrow), whose whakapapa is all but a mystery, walked the shores of the lake. Nine species of waterfowl, (ducks and geese), dominated this ancient ecosystem, making St Bathans the richest fossil site in the world for this guild of birds. Other feathered players in the Wonderland menagerie included the ancestors of the New Zealand wrens, as well as parrots, pigeons, herons, raptors (eagles and kin), swiftlets and sea birds. One exciting new discovery, straight out of Lewis Carroll, is the Zealandian Dove, a close relative of the Nicobar Pigeon, and a distant cousin of that other famous Wonderland resident, the extinct Dodo.

The most famous inhabitant of the long lost world was the ‘waddling mouse’, something that perhaps is neither a placental, (i.e. has a placenta), or a marsupial, (i.e. raises young in a pouch), mammal. New Zealand, long thought to lack terrestrial mammals, now has its own, though the available fossils including teeth, remain frustratingly, enigmatic as to what this mystery mammal really was. What this does tell us, in contrast to popular belief, is that a lack of mammals was not a precursor to flightlessness in New Zealand birds. Mammals were here.

The Manuherikia Wonderland is also just as famous for its absences. Those truant Australians who decided to skip the party, unable to get to New Zealand, despite millions of years of opportunity. Notable examples include marsupials, snakes, ‘dragons’ (agamid and varanid lizards), lung fish, eels, cockatoos, and all but one lineage, (bellbirds and tui), of the 80 species of Australian honeyeaters.

So what happened to this ancient subtropical world? The march of time and climate change was not kind to the inhabitants of Lake Manuherikia. The marked global cooling and drying during the Miocene, and again during the Pliocene and Pleistocene Ice Ages, resulted in the extinction of the ‘subtropical’ elements of the St Bathans’ fauna. Those that survived would go on to adapt to the dynamic geological and climatic changes to come, and would form part of the enigmatic fauna, (supplemented by a few late arrivals from across the ditch), that characterised New Zealand when humans arrived and wreaked havoc.

There’s a famous saying from 1975 by fish scientist Gareth Nelson: “Explain New Zealand and the rest of the world falls into place around it”. The steady stream of fossil discoveries from St Bathans is changing the way we think about the evolution of New Zealand’s biota, and that worldwide – a fossil revolution of sorts. We are still trying to explain New Zealand.

No doubt many more exciting discoveries will be made this field season. With that in mind, it’s hard to take my budding palaeontologist away from the sieves that day. He’s fascinated by these fossilised glimpses of a lost world and the stories behind them. He meticulously checks the progress of each sieve looking for bones. On the way home he excitedly and proudly tells me what he found and asks if we can go back next season to discover more of this strange Wonderland. I think we just might…

This Sciblog has been updated to include the new discovery of the Zealandian Dove.

it was nice to meet you and your kids Nic. it gets pretty hot in the valley i didn’t wait till the end of the day the river was just to dam inviting just a pity for all the didimo.i might see you next year.