Mysterious Chemistry

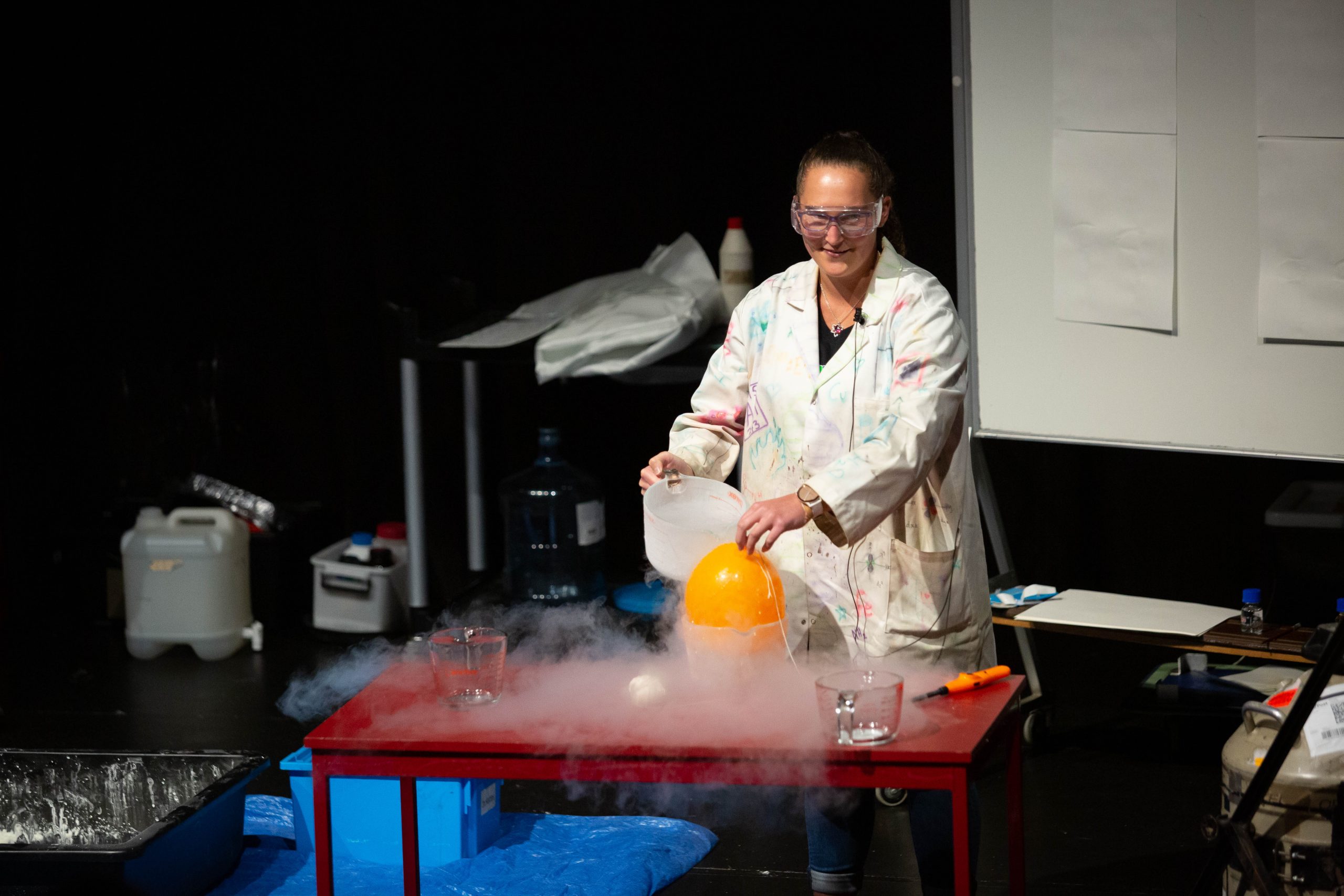

As part of the International Science Festival the team put on a show called ‘Mysterious chemistry’, which was a collection of demonstrations intended to provoke the question “how does that work?”. We ran two shows on Sunday 9th June in the Castle 1 lecture theatre to about 500 people over the two shows. Here are a few pictures to give you a feel of what it was like.

Density bottles

The recent round of outreach has been making density bottles, kids love them and they are very relaxing to watch. The original idea was taken from a paper in The Journal of Chemical Education. (J. Chem. Educ. 2015, 92, 9, 1503–1506, https://doi.org/10.1021/ed500830w)

The top liquid is iso-propanol and the bottom one is a saturated solution of salt. The liquids mix when you shake them but just like oil and water will separate out when you leave them to stand. The beads in the bottle are made out of two plastics, their density is greater than the iso-propanol but less then the salt water so they float in the middle of the bottle. When the bottle is shaken the density of the mixture is between the density of iso-propanol and salt water and one set of the plastic beads are less dense than the mixture and the other set is more dense so they separate out, slowly coming back together as the mixture separates back into it’s components.

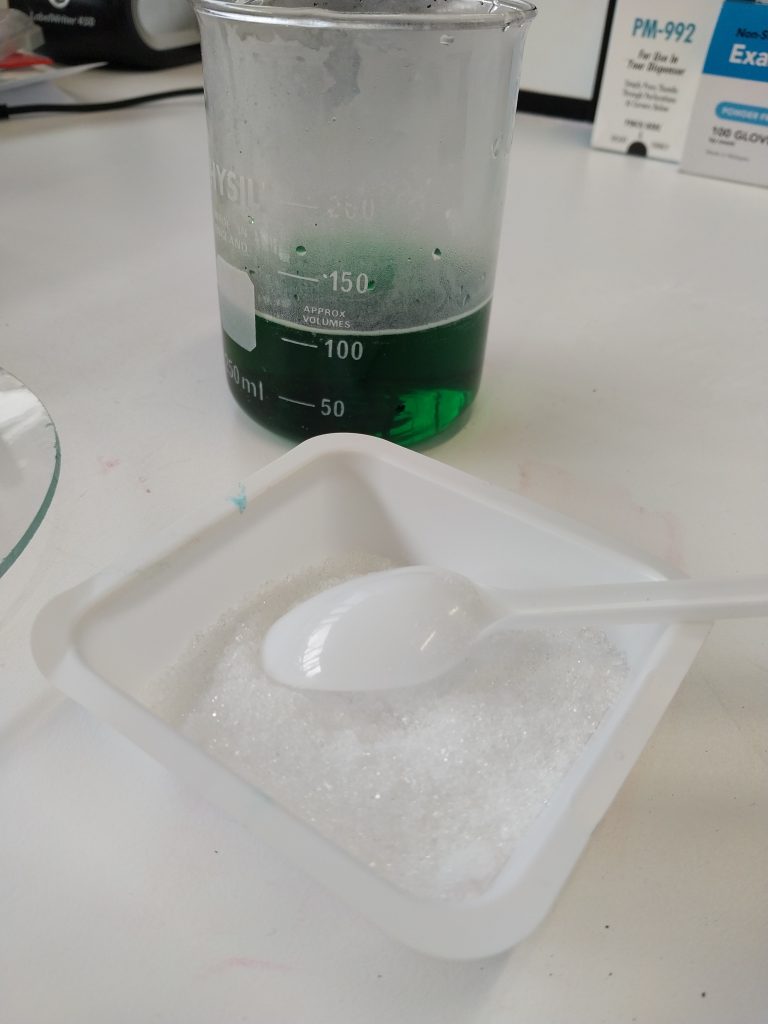

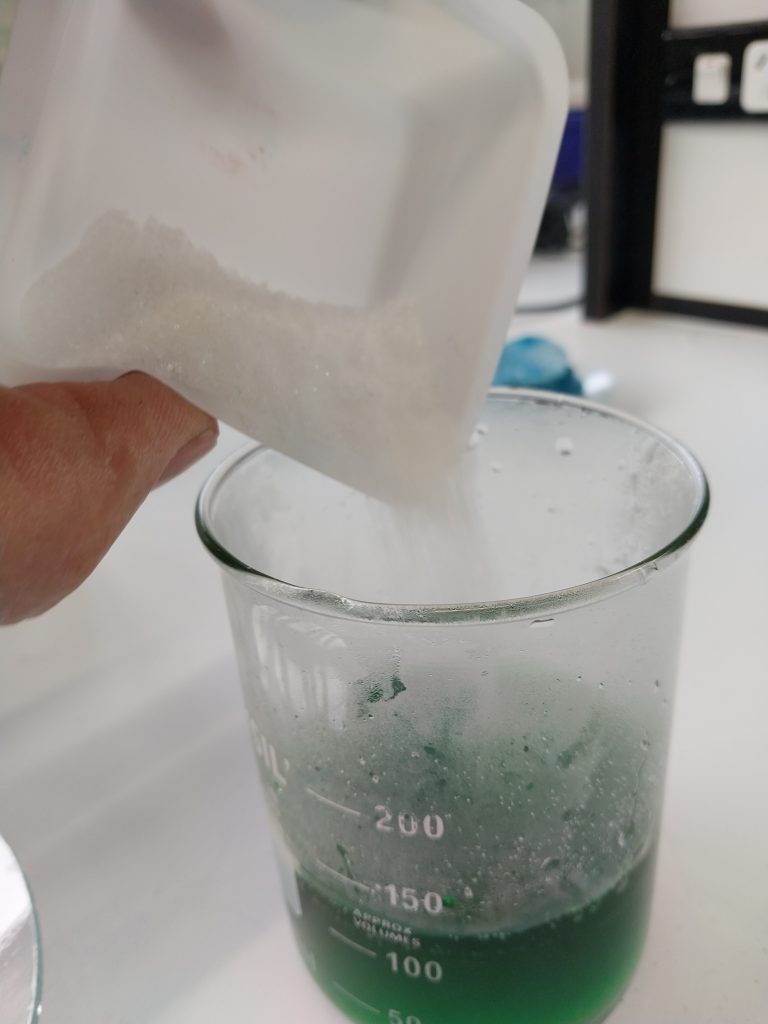

Growing crystals. ALUM

We have three methods for growing crystals. This is the simplest method and can be used for growing alum crystals. It’s the material commonly found in commercial crystal growing kits and the crystals can be coloured using food dye. The chemical name for alum is potassium aluminium sulfate and it is a relatively cheap material with a number of uses including a mordant for dyes and for clearing drinking water.

The process of crystal growing involves creating a saturated solution (no more of the solid will dissolve in the water) at a higher temperature than your room. We use hot water out of a jug and add ~30 to 40 g for every 100 mL of water (5 to 10 flat teaspoons to half a cup of water). Add the dye to the water before you add the alum.

The water doesn’t have to be boiling but the hotter it is the quicker things will dissolve and the more alum will dissolve. If you use cooler water then add less alum, otherwise it won’t all dissolve.

When no more alum will dissolve in the water pour some of the solution over a paper towel or similar on a shallow dish. We use filter paper and lab glassware but it’s not necessary. The paper will hold the crystals together and the shallow dish allows the water to evaporate quickly.

Leave the solution until all the water has evaporated and you should get some nice coloured alum crystals.

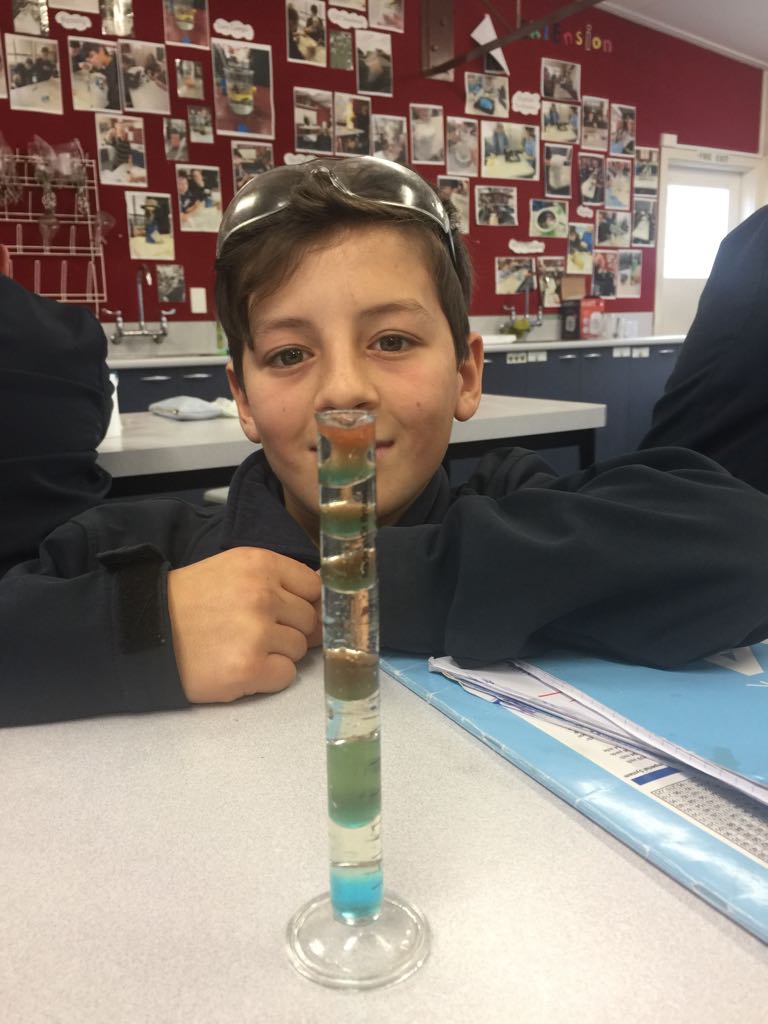

Measuring the density of liquids

One of our basic learning activities is to measure the density of liquids. We use small balances that we can buy off the internet for a few dollars and 10 mL measuring cylinders. Typically the activity starts with a discussion of floating and sinking (sometimes using a helium balloon and liquid nitrogen to change it’s density) and then arrives at the question what is density. In simple terms we talk about ‘how much something weighs for it’s size’ (we use mass and volume but sometimes have to over simplify-apologies to the physicists).

To allow comparison between liquids we control the volume, so the kids measure 10 mL of each liquid. Water (green food dye), canola oil, methanol (red food dye) and saturated copper sulfate solution.

This video shows it a class at Tahuna Intermediate, Dunedin (for this class we also included hexane as a, short lived, experiment).

Quite often we allow the lesson to run after the stage in the video and set a challenge to create as many layers as possible (mixing methanol and water/copper sulfate creates a layer with new density).

The most we have ever seen in 10 years of doing this experiment is 15 layers, keeping layers of water and methanol (and copper sulfate) separated with layers of oil. The narrow 10 mL measuring cylinders are important to keep the layers separate.

Recent comments