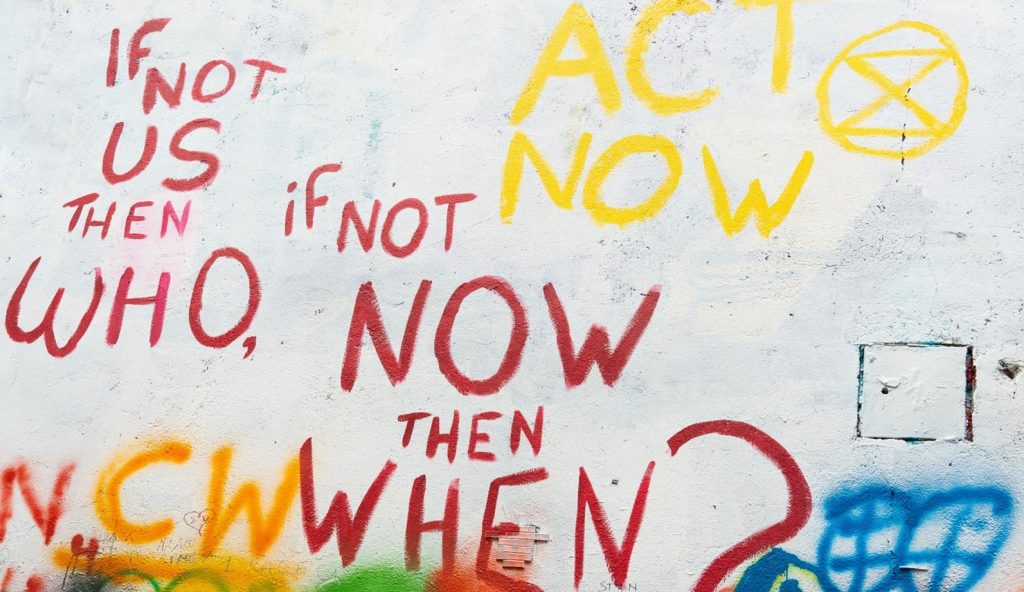

Image credit: Words in coloured graffiti on a wall that say “If not us then who, if not now then when? Act Now.” Photo by Rod Long on Unsplash

The Working Paper Series, Volume 1, Issue 1, pp. 1–2

Published 14 February 2022

PDF Version

Let’s start by labeling things as they are

Alejandra del Pilar Ortiz-Ayala

Te Ao O Rongomaraeroa National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies, University of Otago

Last Friday, I ended the day with a heavy heart. When I met my partner, I told him that there had been a racist attack in a high school in Dunedin, the town where we live in New Zealand.1

Some of the students who are part of the research project that I’m working on have been affected.

After some time, he told me: Alejandra living with you, it’s difficult.

I did not understand and I asked him back: What you mean?

He said: There are some days when I just want to live in this white privileged ignorant bubble, but since I’m with you, it has not been possible. Your work and your life experience are a constant reminder of how the world actually works. It reminds me of the times when I was in school back home and I did nothing when someone was bullying someone else due to their ethnic identity. Reminds me of the times that I decided to remain silence in front of injustice. But, now living with someone who faces those injustices in her daily life and does research about heavy things that sometimes I don’t completely understand, it’s hard.

I get it, it is difficult. It was too difficult for the journalist to write the words “racist attack” when describing what happened in Dunedin last week. Instead, he referred to “a fight” and “an incident”. It was too difficult for teachers at the school to take action when Muslim girls who are former refugees earlier complained about racist bullying, on more than one occasion. I get it, it’s hard for white people when their blindness and the reputations of their institutions are challenged. The voices, feelings, and experiences of people of colour challenge this comfortable blindness, and therefore, people like me are difficult to live with.

For my partner, living with a woman of colour from the global south is difficult, because I activate fear, guilt, and consciousness of the injustice that surrounds us. I’m a reminder of his potential complicity by action or omission. His bubble of white male ignorance is a perfect metaphor of white privilege. None of us can choose our skin color, or where we come from. All of us want to life in a place where our cultures, accents or faith can be expressed with pride.

I’m wondering why some non-Muslim girls at a Dunedin school felt entitled to taunt and attack others in a school space last week…I also wonder about the girls who were watching and recording…As a Political Scientist with a PhD in Peace and Conflict Studies I know that such actions of violence do not occur in a vacuum. Context helps us shape individual decisions and I wonder about the school’s role, not just in this case, but in general.

For most children and young people, schools are the second site of socialisation after family. Hence, schools are our first opportunity to encounter diversity. How schools with diverse groups foster encounters, and promote emotional connections, empathy and humanisation among different groups, will directly affect individuals’ relationship with diverse groups, and the level of social cohesion in society. Therefore, schools have an important responsibility!

No matter how hard or uncomfortable it could be, we need to acknowledge that where an environment privileges ignorant white blindness, or where violence and bullying are tolerated, discrimination and racist events are enabled. School leaders and teachers must listen carefully when students raise concerns about their own safety. They must take action, and rethink their pedagogical practices. Both direct violence, and inaction in the face of the threat of violence, cause harm. The feeling of not being heard, the feeling of being within an institution that does not take violence, bullying and threatening behaviour seriously, sends a message to some of us that we do not belong.

In the past month, I have heard young former refugees and their families from Colombia, Syria, and Afghanistan here in New Zealand describe many experiences of being ignored when they attempted to denounce bullying and discrimination at school. They have been called “terrorists” and “monkeys”; they have been told, “go back to your country”. Former refugees from Colombia have been called “drug traffickers” and “Pablo Escobar,” and subjected to jokes about cocaine. Some young people have had their bags slashed. Some have been threatened by mob violence. In no case did school staff listen when the young people concerned raised concerns. In no case did they take decisive action in response.

I am Colombian, like some of these young people. I wonder if the students who threatened them, or the schools that ignored the threats, know how many people in my country have died due to the war on drugs, or how much displacement has been caused. Some of the young people and their families have been running for their whole lives to escape from violence. For all of the young people, New Zealand was a promised “safe place” – in Spanish, a casita. But instead, they have encountered further violence.

The dehumanisation of those who are seen as “different” in terms of their ethnicity or faith is an urgent issue in New Zealand. The worst outcome of dehumanisation was starkly evident in the March 2019 mosque attack. According to the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the attack, social cohesion is needed to help fight radicalisation, and the growth of white supremacy in New Zealand. But little has been said about how to foster social cohesion in concrete terms. I would suggest that schools would be a great place to start.

To the Muslim students involved in last week’s attack, keep speaking up and helping us to make our institutions accountable. This is a collective responsibility; we need to pop the bubble of privileged ignorance. And let’s start by labelling things as they are; what happened last week in Dunedin was a racist attack.

Note from the author: On the 16th of February, seven days after the attack, ODT published again, labelling the event as an “Islamophobic motive alleged for ‘brutal’ attack”2. I celebrate what media have done. However, school silence remains.

Notes

- See more in https://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/school-fight-video-prompts-action

- See more in https://www.odt.co.nz/news/dunedin/school-fight-video-islamophobic-motive-alleged-brutal-attack

Alejandra Ortiz Ayala received her PhD from the National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Otago and holds a master’s and bachelor’s degree in

Political Science with minors in Comparative Politics and Political Theory. She has worked as a lecturer, research and consultant for national and international organisations.

© 2022. This is provided as an open access article by The Working Paper Series with permission of the author. The author retains all original rights.