On a dark and stormy Wellington street, Kerry is head down, bum up, searching for an elusive and rather dull looking snail.

Kerry is one of a new breed of up-and-coming scientists that is taking up the mantle of taxonomy (the science of describing and naming new biodiversity) as members of the old guard get closer to imminent retirement. As one of New Zealand’s foremost experts in terrestrial and marine shells, Kerry is at the forefront of a scientific revolution that, as the whole field becomes more interdisciplinary, is seeing the latest genomic techniques and ancient DNA brought to bear on taxonomy.

Just hours earlier, somewhat inebriated, Kerry had been weaving his way home from a night out when he noticed a weird snail (an LBJ or little brown jobbie as it’s known in the field) and thought nothing of it…until later. Now, it’s a scene eerily reminiscent of Gollum feeling around in the dark of the goblin cave for his precious. He needs to find that LBJ; it may be important.

After careful comparative study alongside Te Papa’s Bruce Marshall, and scouring specialist libraries, Kerry’s LBJ snail (and its mates; it was not alone) turns out to be the highly-invasive Girdled Snail (Hygromia cinctella) from Europe. In a perfect example of public outreach and citizen science, in the spirit of a low-budget Western film, Kerry and his team, including DOC and MPI, set about placing ‘wanted’ posters in local primary schools to marshal an army of hobbits. It turns out that populations of this little critter are present in Brooklyn and Tawa. No doubt now established throughout the region, this miniature invading army is probably here to stay.

Discoveries like this one, or the recent discovery of a new marine fly in Otago, highlight there is still work to be done in Aotearoa, whether it’s eureka moments like finding a new, charismatic, extinct species or the more mundane, applied research identifying invading LBJs.

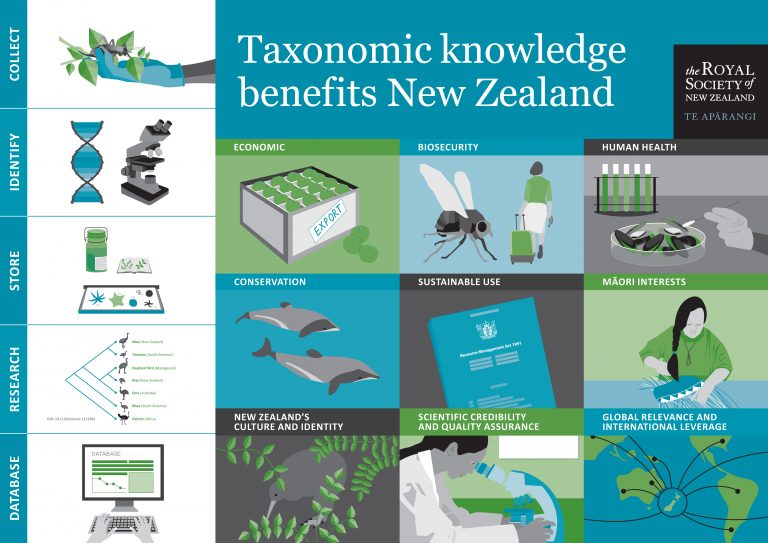

Far from being a dying science filled with old, bearded scientists, taxonomy (as I tell my undergraduate Evolutionary Biology class), is one of the lynchpins of biology. It provides the base of everything from biosecurity to medicine and conservation. Taxonomy is vital to DOC’s Deep Thought computer algorithm, used to calculate which species are worth saving, (a highly emotive and contentious topic indeed). MPI would not be able to fulfil their biosecurity mandate without the work of taxonomists.

But, and there is a big but, I cannot lie, unlike other areas of natural science that attract large competitive research grants, taxonomy often runs on the smell of an oily rag, or is a by-product of more sexy projects focusing on big-picture questions. To channel Donald Trump “How do we make taxonomy great again?”, ensuring this keystone field of science continues into the future.

The recent release of Discovering Biodiversity: A Decadal Plan for Taxonomy and Biosystematics in Australia and New Zealand by the Royal Society Te Apārangi and the Australian Academy of Science, (as well as the 2015 National Taxonomic Collections in New Zealand report), is a timely reminder that all is not kua ngaro i te ngaro o te moa (lost as the moa was lost).

The global uproar from fellow taxonomists on Twitter over the release of Conal McCarthy’s report from Victoria University of Wellington, commissioned by Te Papa to shape their thinking moving forward, shows the aroha for taxonomy is alive and well. McCarthy’s assertion of “whereas much museum staffing, time and resource is taken up by taxonomic research, he [Frank Howarth] observes that this area is fast becoming outmoded, and that the use of whole specimens, and even the notion of separate bounded species, has been superseded by developments in bioinformatics and genetics”. Howarth, who was previously Director of the Australian Museum, was writing in a recently released book ‘The Future of Natural History Museums’ edited by Eric Dorfman, currently Director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Dorfman used to be Senior Manager of Science Development at Te Papa and Director of Whanganui Museum. The views expressed by these three ‘experts’ are so far left of field, I feel like I’ve stumbled onto the set of an Oscar Wilde satirical play, or a parallel universe in Doctor Who.

As a scientist of two worlds (much like Spock from Star Trek) having worked in both the Australian and New Zealand science systems, I certainly feel qualified to comment on this. So what are some of the ways we, as a Kiwi and global scientific community, can increase the profile of taxonomy? What do you think? I’d love to hear your ideas.

Increased funding

Across the ditch on the other side of the Tasman, funding for scientific research is considerably easier to obtain than here in Aotearoa. Just as Australia has its unique wildlife and varied landscapes, it also has a unique funding system, with the Australian Biological Resources Study offering substantial funding for taxonomic-based projects, including the provision of postdoctoral research fellows. These projects don’t have to be big picture or sexy, just solid science.

The Australian government, in collaboration with museums, also funds bioblitzes (the Bush Blitz scheme). I once spent a wonderful week in the middle of the Australian outback on a bioblitz helping find native bee species new to science, and got paid $1000 for my troubles, with all specimens collected going to museums for taxonomic research. Bioblitzes are beginning to take off in New Zealand, like the recent one I attended with Auckland Museum and Ngāti Kuri, where I experienced the welcoming hospitality and natural history delights of the winterless north.

Here in New Zealand, external grant funding for taxonomy is limited to DOC’s Taxonomically Indeterminate and Data Deficient Species Fund, which operates fairly randomly, no doubt due to years of consistent underfunding by governments. This funding is limited to $10-20K at the most.

Additional funding is sorely needed, even if only to stem the haemorrhage of retiring taxonomists. There has been a 10% decline in the taxonomic workforce in Australia in the past 25 years, with declines of around 22% in New Zealand over a similar time period. Both here and across the ditch, a steadily increasing proportion (currently around a quarter) of taxonomists are unpaid or retired.

Increased funding could not only be used for taxonomic research into our unique flora and fauna, of which a large proportion is currently undescribed, but also on research into the parameters and vocabulary we use to describe species, especially in this new and strange genomic world.

Species concepts, and there are quite a few of them, tend to attract considerable and vitriolic debate. Miss Prism’s three-volume romance novel in Wilde’s The Importance of Being Ernest (“Do not speak slightingly of the three-volume novel, Cecily”) is a lesson in what happens when you try to impose an impossible, idealised, world onto an everyday reality. I have been involved in one of these Oscar Wilde style debates over species concepts; not rewarding stuff!

Funding is one thing, but the success of taxonomists getting funding could be enhanced if we scientists changed the way we cite taxonomic research.

Publish or perish

Every species name has a taxonomic authority or provenance, associated with it. For example, Psephophorus terrypratchetti, an extinct Antipodean turtle, is named in honour of the novelist Terry Pratchett. In this case, its authority or provenance is Psephophorus terrypratchetti Kohler 1995. These authorities, which relate to a specific publication, and in some cases a historic painting, are big business in taxonomy. Older names/dates have a higher priority in the hierarchy in cases where groups have been named more than once. New Zealand’s critically endangered Orange-fronted Parakeet (Cyanoramphus malherbi Souance 1857) has also been described as Platycercus alpinus Buller 1869.

One of my tasks on the Birds NZ Checklist Committee is to resolve these debates in light of new evidence. Yet, in the publish or perish world of academia, where citation indices (i.e. how well you research is received by the scientific community) are everything, you do not have to reference taxonomic authorities. If we do cite these authorities, it will allow scientists to increase their citation indices, which will no doubt help obtain research funding.

Public face of taxonomy

In the instantaneous news feeds of the social media age taxonomy badly needs a facelift of Hollywood proportions. The field needs to be made more attractive to the new, up-and-coming guard as a real and valid career choice.

As a child, I dreamed of discovering and naming exciting new species; I’ve managed to name a handful so far in my career. Not everyone is so lucky, so an undergraduate Methods in Taxonomy paper would be a start, encouraging collaboration and consultation with museums and experts throughout New Zealand. An increased awareness of the field would result.

Increasing the social media profile of taxonomy through Facebook, Twitter and Instragram would also be vital to this facelift. Te Papa’s Carlos Lehnbach, Cambridge University Zoology Museum’s Jack Ashby, and CSIRO’s Bryan Lessard (aka @BrytheFlyGuy) do a fantastic job of putting taxonomy in front of the media. Any scientist can have a go at increasing the profile. A Science Media SAVVY course from the New Zealand Science Media Centre is a good place to start; their courses have been worth their weight in gold to me.

However, while a public presence is all well and good, access to museum collections, those cathedrals of taxonomic research for centuries, is the key. You can’t talk authoritatively about taxonomy if you have not done your homework or the prescribed readings.

Museum collections are the keystone of taxonomy

In this uncertain world, when museum collections are increasingly devalued worldwide, we are in real danger of losing access to these precious genetic resources. Museums need to be better funded and supported so that their scientists can undertake and facilitate taxonomic research. Like archives, collections are not about stamp collecting, but are there to be used, rather than gather dust locked up in Fort Knox-style institutions.

As the field of biology becomes increasingly genomics and DNA centric, museum collections are more important than ever as repositories of voucher and type specimens (those that own their name). Without replication, a key Greco-Roman pillar in the scientific method, there is no point publishing new species descriptions based on DNA if there are not vouchered type specimens, housed in properly-curated museum collections. They cannot be stored in the back of a fridge that suffers an annual cleanout by the lab manager. Rather than the post-apocalyptic world that Conal McCarthy and co are insinuating, where taxonomy is dead and buried, DNA is not the be-all-and-end-all. It’s not the only tool in the taxonomic toolbox; morphology and the use of whole specimens are just as important.

Next time you find yourself in a museum collection, have a walk up and down the aisles; you never know what you may find. It could be a new species, or long-lost specimens that could resolve the taxonomy of an enigmatic group of highly endangered animals. It could be examples of the LBJs that are feasting on the Rengarenga in my garden. Then take action: broadcast your findings via the media and social media. Let’s make taxonomy great again!

Somewhat tangential to the POV of the blog, although I can add that iNaturalist.org is great for stimulating public interest in taxonomy and educating people about species, because scientists can easily interact directly with citizens posting their photos for mutual benefit. So I checked iNaturalist for observations of the Hygromia cinctella snail in New Zealand. There are no (zero) citizen observations of it, although Stephen Thorpe in 2016 put it on a checklist https://www.inaturalist.org/listed_taxa/9201184 and gives the original Wellington record reference. I’ll be keeping an eye out for it.

Yess, need more invertebrate taxonomists especially. Lots of undescribed species in New Zealand which can make other aspects of research more challenging as we have to resort to morphospecies. Or maybe i should become a taxonomist myself.

I am the coordinator of a restoration project on the Kapiti Coast where one of the objectives is to measure the response of the invertebrate community to predator control using malaise and pitfall sampled adult beetles. The taxonomic identification process has proven far more difficult than I estimated thinking that what we would catch would be easily identified. But this has not been the case and we are now applying for funding to have a recent PhD do this work for us. To me, this highlights the critical need to significantly improve our invertebrate taxonomic understanding, and this is essential if we are to successfully engage in their conservation management.

I would certainly consider taxonomy, if there were an established career path for it, i.e, a job…

Great article, highlights so many of the pressing issues in our field. I wanted to add that there IS an undergraduate taxonomy course available in New Zealand–we started one at AUT just this year! Hopefully the first of, if not many, at least several… 🙂

@Jim O’M

Having a “recent PhD do this work for us” might sound good, but actually what you need is someone like, well, me, with decades of experience identifying NZ beetles. Otherwise, you could easily end up paying a significant amount of money for a low quality result which would waste a great deal of time!