I’m lying on a beautiful golden sand beach. The bright sun is beating down upon me. I could be on an isolated, tropical island, if not for the lone giant moa sculpture looming above my head.

This sentinel to a lost world stands at the aptly named Old Bones Backpackers at Awamoa, (originally named Te Awa Kōkōmuka), south of Oamaru. It was erected as if to remind us of what was and what we have lost, guarding the remains of its brethren.

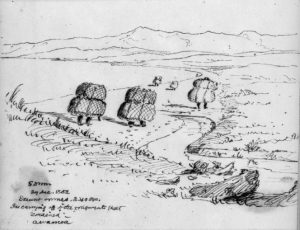

Awamoa is a ‘moa hunter’ site where one of New Zealand’s first archaeological excavations, conducted by Walter Mantell, took place in 1852. Today, it’s a far cry from what the area looked like all those years ago, with coastal erosion, the nemesis of archaeologists, attempting to wipe the slate clean.

Suddenly, waves crash around me into our excavation pit, followed by the rhythmic upbeat music of the water receding over pebbles. It breaks me out of the reverie about my curious feathered friend. I’m here on what could only be called an extreme ‘rescue excavation’ before the sea claims any remaining bones for Davy Jones.

The excavation pit is a veritable, prehistoric, compost heap. Giant Pāua/Abalone shells jostle for space with partial moa eggs. The bones of these giant birds are tangled with those of Rāpoka/Hooker’s Sea Lion, Ihu Koropuku/Southern Elephant Seals and Kurī/Polynesian Dog, much like a prehistoric version of ‘pick up sticks’. Everything is completely jumbled, giving the impression that last night’s scraps were thrown over one’s shoulder onto the compost, just after dinner was finished. Now, the bones are encased in a hard matrix of sand, charcoal and ancient fat or oil from the butchered marine mammals and moa. Indeed, there were that many animals killed or eaten at Awamoa that a fairly thick layer of fragrant oil covers the water in our excavation pit the next morning. I’ve given up trying to get it out of my field gear.

While some of the bones at Awamoa and at other archaeological and palaeontological sites in New Zealand, are identifiable, a large proportion aren’t, which end up on the taxonomic scrapheap. It’s like the key pieces of this prehistoric jigsaw puzzle have been chewed up and spat out, (or worse still, eaten), by a hungry toddler, much as my youngest deals with puzzle pieces now. It leaves me wondering what piece that was and where it fits. ‘Frag bags’, containing thousands of these small pieces of unidentifiable bone take up lots of storage space, much to the annoyance of museum curators. However, it’s these very bone fragments that are allowing us to reconstruct a lost world like never before.

Environmental DNA, the same cool kid that put the cat amongst the pigeons for the traditional Chinese medicine and herbal remedy industry, can also be used to illuminate our prehistoric jigsaw. Called ‘bulk bone DNA’, these ‘frag bags’ can be thought of as just another environmental sample, a treasure trove of ancient genetic information, and that’s perfect for us DNA time-lords, worthy of the space they take up on museum shelves.

‘Bulk bone DNA’ allows us to cost-effectively characterise all the biodiversity within these ‘frag bags’. The same technology can also be used on water, sediment, fossilised moa poo and even what’s hiding in Loch Ness! The power of this technique is the speed scientists can do a biodiversity audit, which would be impossible for individual unidentifiable fragments of bone. Isolating the DNA from these ‘frag bags’ and sequencing a genetic barcode, common to all biodiversity, allows us to distinguish each component within. However, like all new, cool techniques, ‘bulk bone DNA’ should not be viewed as a replacement for more ‘destructive’ methods, but rather just one tool in our varied toolbox to reconstruct lost worlds.

I was lucky enough to be involved in a study, with collaborators from Curtin University in Perth; Te Papa; Canterbury Museum and the University of Otago, that has just been published in the prestigious international scientific journal PNAS. We used ‘bulk bone DNA’ on New Zealand’s pre-human fossil and prehistoric archaeological sites, including Awamoa, to conduct a fossil ‘lucky dip’ from a lost world. Our goal was to reconstruct what our little slice of heaven was like at the time of Polynesian arrival, how it has changed, and how the ancestors of Māori lived in that environment.

Our knowledge of New Zealand at this time is far from complete. The jigsaw is only partially finished, (‘Don’t chew on that’.), and several key questions remain. Important food sources, like tuna/eels and cetaceans, (wēra/whales and pāpahu/dolphins), have been under-represented in archaeological deposits.

But first the numbers. We genetically identified over 5000 bones, spanning 20,000 years of New Zealand’s history. Those bones came from 15 fossil and 21 archaeological sites across the length of Aotearoa. Within this very large pile of degraded puzzle pieces, we found 110 species of birds, fish, reptiles, frogs and marine mammals.

So what were some of the surprises we found? Well, Southern Elephant Seals for one: yes, these giant burping and farting sacks of blubber were probably breeding in New Zealand. These “Monsters of Yore”, and sea lions, formed as important a part of the diet of early Māori as Kekeno/New Zealand Fur Seals, until their extinction around the same time as moa. Indeed, at the base of the Awamoa compost heap, we found a complete skull of an elephant seal, beautifully preserved and complete with its large canines.

A wide range of cetaceans were also utilised for food including Maki/Killer Whale, dolphins, Cuvier’s Beaked Whale, Fin Whale and Tohora/Southern Right Whale. While the presence of the larger whales no doubt represents scavenging of beached individuals, the smaller species are probably indicative of deliberate hunting, (especially their association with bone harpoon heads in some sites), a controversial suggestion in New Zealand archaeology indeed.

The prehistoric version of the local fish and chip shop was also in high demand. Much like today, locally caught fish was a selling point; it wasn’t shipped in and locals were very loyal to their own shop. Amongst the bone fragments were also the genetic signatures of eels we had been hunting for; not just freshwater species, (Tuna/Short-finned Eel), but also marine ones as well, suggesting eels were important seasonal food sources for pre-European Māori.

Our feathered friends, not surprisingly for a ‘land of birds’, were also very common; at least 54 different species. ‘Bulk bone DNA’ also showed that Polynesians had a large impact on species previously thought not to have been affected, including Kea and Kākāpō. The North Island had its own unique lineage of Kākāpō that is now extinct. Contrary to previous studies, Kākāpō in the South Island lost a significant amount of genetic diversity in these pre-European Māori times.

In a nice surprise, we were also able to find the genetic fingerprints of New Zealand’s long lost frogs, including the extinct Markham’s Frog. The amount of genetic diversity in Markham’s Frog is remarkably similar to that seen between Archey’s, Hamilton’s and Maud Island Frogs, which we had previously suggested were a single species heavily impacted by climate change, predation and habitat loss. Ancient DNA time and again, is showing its key to resolving the whakapapa of New Zealand’s unique biodiversity.

‘Bulk bone DNA’ is telling us an exciting story. It is filling in many of the blanks in the critical period in Aotearoa when humans first interacted with our unique fauna. In some cases, it is demonstrating that the picture on the jigsaw box we were using to build our lost world is the equivalent of a child’s paint-by-numbers version of the Sistine Chapel, lacking many of the crucial details. In other instances, the picture on the box may be wrong; it may belong to an entirely different puzzle altogether, a humbling thought indeed.

On a recent visit to Oamaru, with this thought in mind, I swung past Awamoa and its lone moa, still standing guard over any old bones remaining beneath the sand. I’d like to think that this moa, one of the last of its kind, would approve of the new pages we have added to the dynamic history of Aotearoa.

Kia ora Nick,

Cool article, the analytical techniques within, and results from, the DNA bulk-sampling methodology continue to be fascinating mate! Great work! Some of the behavioral conjecture from the archaeologist is not ideal, but that’s archaeologists for you, he aha. Please pass on my regards to Maria and the whanau, e hoa.

Ngā mihi,

Kyle