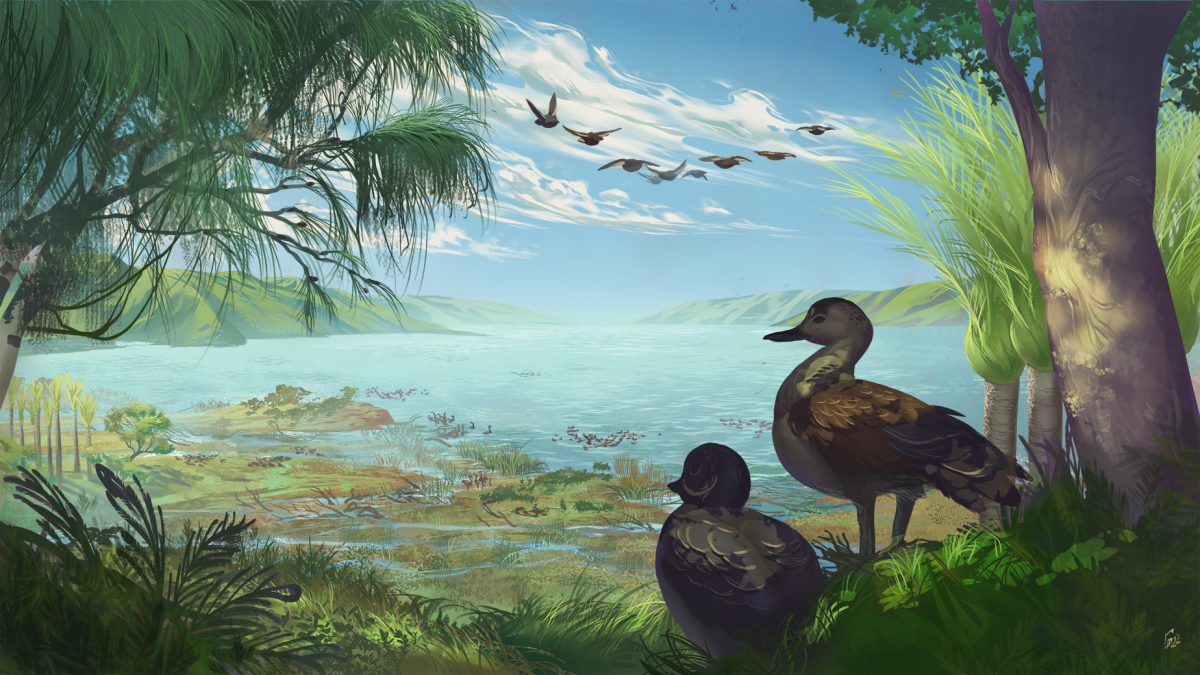

In the depths of winter, most people from southern New Zealand head to warmer climes for a much-needed dose of Vitamin D. Yet during the height of the last Ice Age, one species of moa did just the opposite.

I’m reminded of Bill Bailey’s En Route to Normal tour that visited Dunedin last year where he was performing one of his great comedic songs. On this night he was singing about being at a dark deserted crossroads, framed by a lone street light, with only a kiwi for company. The punchline, delivered to peels of laughter from the audience, is that it was a Friday night in Invercargill. This comically disparaged city is New Zealand’s southernmost, just a few hours down the road from here, and the butt of many local jokes. I strongly suspect Bill’s song was about Dunedin when performing for his Invercargill fans. Continue reading “It’s a Friday night in Invercargill for eastern moa during the Ice Age”