CROCC’s first event for 2019 concluded successfully on Friday 25 January. Dr Rosi Crane, a graduate of Otago History’s PhD programme, an Associate Member of the Centre, and the Museum’s honorary curator of science history organised ‘Held in Trust: Curiosity in Things’, a conference, held at, and in conjunction with the Otago Museum which commemorated its 150th anniversary last year. A range of people, both academics and heritage sector professionals, attended and presented, with most topics relating to collections, collecting and practice in museums from the colonial-era to the present. See also Otago Humanities story about the conference.

Tony Ballantyne (University of Otago) provided the first keynote, ‘Cultures of Collecting in Colonial Otago’ on Thursday morning. He noted that notions of “improvement” stimulated the development of intellectual life and culture in early Otago. Several points resonated through many of the following talks: that local enthusiasm, activity and donations allowed institutions such as museums, and even New Zealand’s first university, to be founded and developed; that collecting pervades colonial culture; and that scholars should always be cognizant of the interplay between words and objects. Tony’s talk highlighted the work of Herries Beattie, a local historian who recorded extensive mātauraka from Southern Māori, but was also an inveterate collector of texts and things, with his collections now housed at the Hocken, Otago Museum, as well as museums in Gore and Waimate. See ODT story.

In ‘“My dear Hooker”: the botanical landscape in colonial New Zealand’, Rebecca Rice (Te Papa) explored the New Zealand “flower painting” of Georgina Hetley and Sarah Featon in the late nineteenth century, whose botanical work was popular but largely unsupported by the scientific world overseen by the likes of Sir James Hector in New Zealand, and Sir Joseph Hooker in the UK. Rebecca’s paper stressed the need to acknowledge women’s contribution to science in New Zealand.

Linda Tyler (University of Auckland) looked at the John Buchanan, who worked with Hector at the Colonial Museum, his botanical draughtsmanship and his extensive (if poorly labelled) collections of botanical specimens. Indeed the sending of material to the UK assisted in Buchanan’s ambitions to be recognised as a botanist of note.

It was the practice of medical schools to create collections students could learn from; Otago, which established its first Chair of Physiology and Anatomy in 1874 is no exception. Chris Smith (University of Otago) gave a fascinating account of the collections of Otago’s Anatomy Museum, its many specimens of flesh, organs and bones, and models constructed from plaster, wax or papier mache. Early professors, interested in racial difference, sent their medical students out to scour burial sites and other places for Māori human remains; the Museum’s koiwi Māori collection is now in the process of being returned to local iwi.

Justine Olsen (Te Papa) discussed the cabinetmaking objects produced by Anton Seuffert and Johann Levien from the 1850 to the 1880s. Their high-quality pieces featured in international and colonial expositions as examples of New Zealand craftsmanship while showing off the various New Zealand woods. Seuffert collaborated with the carver Ferdinand Teutenberg to produce items sought-after by New Zealand’s elite. Featuring designs influenced by Ferdinand Hochstetter, their work points to New Zealand’s German network of the late nineteenth century.

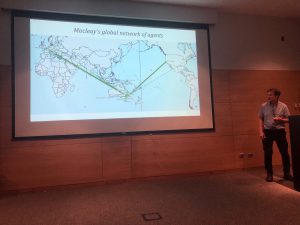

The first day was brought to a close with the keynote of Simon Ville (University of Wollongong), ‘The exchange, finance and logistics of natural history: a global trade like no other?’ Simon is part of an inter-disciplinary team focussing on the collection practices in the nineteenth century of the MacLeay Museum and the Australian Museum. The accumulation of dead creatures (or parts of them), involved purchases from collectors and trading firms, exchanges between institutions, financing field collections, or donations, all of which could be problematic. He argued that the commerce in “natural history” does not appear to adhere to the ideal conditions for trade and exchange, but despite its difficulties still managed to survive.

David Gaimster (Auckland War Memorial Museum) began the second day with ‘Fitting the colonial museum dashboard? Curatorial agency, civic action and identity building at the Auckland Museum (1852-1917)’ on the early days of the institution that he is responsible for. David explored the synergies of civic action of local Aucklanders to found their museum with the imperial networks that enabled it, and how the “successive intentions” of curators shaped its practice and exhibitions. In particular, serious scientific enquiry and disciplinary presentations sat at the edge of the museum’s other aim, to amuse or educate the wider public. More so than some other countries, New Zealand museums collected artefacts from its indigenous people, a process that Māori themselves, in some part, were able to control.

Rosi Crane (CRoCC, Otago Museum) turned to the work of the first three curators of the Otago Museum with ‘What were they thinking? Tracing the traces of scientific thought through the Museum collections (1868-1939)’. Unlike other museums, the Otago Museum was part of the university, with the early curators, Frederick Hutton, Thomas Jeffery Parker and William Benham mixing academic teaching roles with building and maintaining their collections. Rosi traced their scientific interests, as the museum expanded. All three were ardent evolutionists, but felt compelled at times not to advertise the fact in their museum displays.

Most of the conference attendees were probably unaware of the influence of Korean art in New Zealand ceramics. While Chinese and Japanese ceramics are often seen as pioneering, Korean art is just as significant, and the three nations influenced each other over many centuries. Grace Lai (Auckland War Memorial Museum), in ‘Inequality of knowledge: reinvestigating the influences of Auckland Studio Pottery through the lens of Korean ceramics’, discussed the extensive collection of Korean pottery held by the Auckland Museum, and how, after the opening of the Hall of Asian Arts in 1969, this influenced Auckland’s potters.

The burning bush (Exodus 3) has been an enduring symbol for Scottish Presbyterianism from the 1600s, and was subsequently exported to New Zealand with the Free Church migrants in 1848. Steve Taylor (Knox Centre for Ministry and Leadership) explored this theme in ‘The symbol of the burning bush as an object in global exchange and local adaptation’. The image appears in books and bookmarks, and has even in flower beds, and portrayed through the Scottish saltire forms the New Zealand church’s current logo. Steve elaborated on how the Scottish symbol had been reframed and transformed through culture, such as in the blue, frangipani-graced burning bush stained glass window at St Johns Papatoetoe, reflecting the churches links to the Pacific Ocean and its peoples, and the stylized “glowing vine” of Te Aka Puaho, the Māori Presbyterian Synod.

Kane Fleury (Otago Museum) expounded on the Museum’s extensive Lepidoptera collection in ‘Books and drawers full of moths’, much of it the work of the still-living collector, Brian Patrick. The museum has been involved in several collaborate moth-related projects: Mothnet, “citizen science” working with school children to collect and report on the moth populations, and the production of guides of New Zealand moths both in English and te reo Māori and the digitisation of the Museum’s extensive moth collections. By comparing the notes and collection data of historic moth collection with more current data, the Museum is helping to understand how environmental change is affecting our rich moth fauna.

The mauri of places and resources were often embodied in kōhatu (stones) that maintained and safeguarded their wellbeing. This, of course has implications for museums that hold such taoka, but that might also produce their own embodiments of mauri. Rachel Wesley (Otago Museum) explored this kaupapa in ‘Kōhatu Mauri: an exercise in practice across cultures’, discussing how the Museum had created its own kōhatu mauri from within its collections. Unlike traditional iterations, whose tapu might preclude physical contact, the modern kōhatu are placed to be touched by museum visitors. Rachel explored the implications of this, and the conflicting values and preservation practices of the museum and mātauraka Māori, and how an accessioned item that ordinarily is only for viewing might be recontextualised (and de-accessioned), changing from mere geological artefact to a taoka with new meanings.

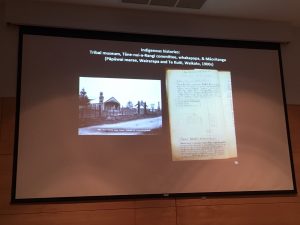

Conal McCarthy (Victoria University of Wellington) was given the hard task in his keynote, ‘From curio to taonga: 150 years of museum histories, theories and politics’ to wrap up the conference, of drawing in the preceding talks, while also giving his take on New Zealand’s museums’ own pasts, presents and futures. Conal, acknowledging that museums were part of a wider colonial culture, looked at how museums had interacted with tāngata whenua and their culture, again stressing that Māori had often been involved in how Māori material might be exhibited. He also noted that Māori had sometimes had their own museums, such as the Kotahitanga base at Papawai, and that individuals such as Ngata and Buck through their involvement with ethnology, museums and heritage, had been prominent in how Māori culture might be seen. But New Zealand had now come to a time when museums needed to find new ways to engage with indigenous peoples, in particular through employing whakapapa as a practical ontology for the future.

The conference had a great buzz, with the single-stream format, a diversity of topics, and the generous coffee breaks allowing the sixty-odd people who attended to engage in many fruitful exchanges. Many congratulations to the organiser, Rosi Crane, on hosting such a fun and productive conference. She is now investigating how some of these presentations may be converted into published research outputs.