Social anthropologists have the tricky task of communicating knowledge about complex cultural and social lifeworlds.

In some fundamental ways “Anthropology is a writing discipline”, as Carol McGranahan discusses in this book (just click ‘read the introduction’). This is because writing has long been part of the process, as well as the product, of social anthropology. However, film, photography, and other creative mediums can be a wonderful part of the process of communicating anthropological knowledge too – and also have a long history in the discipline.

Below we explore some of styles of writing anthropologists get up to, as well as some of the other mediums for communicating ethnographic knowledge.

Writing

When social anthropologists write about a culture, community, or society, it is called an ‘ethnography’ (which, somewhat confusingly, is both the name of the type of fieldwork social anthropologists do, and the texts they produce). This page gives a great 3-paragraph intro to what an ethnography typically looks like, as a text, and why they are useful.

However, not all ethnographies are alike. Writing produced by social anthropologists has changed over time, and been shaped by different ideas and different fields, from a very scientific ‘realist’ form involving detailed descriptions, with a distanced, objective voice; to more evocative, ‘impressionist’ descriptions of a place and peoples; to narrative-driven ‘confessional’ tales that make visible the writer/anthropologist’s own struggles, mistakes and triumphs, as part of the story. These three ‘genres’ of writing were described by American professor John Van Maanen. There are other ways of thinking about our writing though, and the important thing to note is that many forms of anthropological writing co-exist today. This useful web page briefly lays out some of the things that social anthropology values in writing, no matter the style/genre.

However, not all ethnographies are alike. Writing produced by social anthropologists has changed over time, and been shaped by different ideas and different fields, from a very scientific ‘realist’ form involving detailed descriptions, with a distanced, objective voice; to more evocative, ‘impressionist’ descriptions of a place and peoples; to narrative-driven ‘confessional’ tales that make visible the writer/anthropologist’s own struggles, mistakes and triumphs, as part of the story. These three ‘genres’ of writing were described by American professor John Van Maanen. There are other ways of thinking about our writing though, and the important thing to note is that many forms of anthropological writing co-exist today. This useful web page briefly lays out some of the things that social anthropology values in writing, no matter the style/genre.

This recent book chapter, by Italian anthropologist Franca Tamasari, also deeply discusses reflexive practices as part of writing.

Below we explore some of the forms in which ethnographic writing can be presented and shared.

One such anthropologist is Zora Neale Hurston, who was a prolific novelist and (as described in a bio by the Association for Feminist Anthropology, 2020) an accomplished journalist and playwright.

This webpage showcases some of her books, both fictional and non-fictional.

Anthropologists, using ethnographic methods to gather data, sometimes use poems to tell stories about the people and communities they have worked with (often within or alongside more standard academic forms of publication).

Poetry can enable people to reach into intangible parts of human experience that academic writing isn't always adequate to express.

Drawing from ethnographic data can bring a richness of both detail and context to a poem. But anthropologists can also use poems to reflect on their own experiences in the field (and in wider life). This poem called 'Fieldwork' (left) by New Zealand anthropologist and poet Michael Jackson, is an example which does both.

As with many things, there are often debates about what makes a poem 'ethnographic'. This transcribed interview with Professor Ather Zia, who writes ethnographic poetry, covers this question, and lots more about the genre as well.

Autoethnography: cultural analysis through personal narrative. Image Title: NoName#6 Acrylique collage et encaustique sur toile, 2017. Image source: Fpoiriernkpa / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

The text of an autoethnography is usually written in first-person, with the author's own self considered an 'object' of analysis - in other words, they are a participant in their own research project. Their self-narrative is inseparable from their cultural analysis. This does not mean other people/participants are absent - the lives and stories of other people are told through the author's story.

Autoethnographies sometimes contest ideas of what makes scientific research 'valid', blurring the lines between objectivity and subjectivity (something we touch on in our researching section under Positionality). You can find a bit more of an overview on this webpage.

Image, Sound and Movement

For a long time, anthropologists have been using both audio recordings and visual techniques to help them record their experiences during field work (including sketches/drawings, diagrams, photos, film, and audio clips of interviews, singing and music).

This page shares the work of the ‘Sensory Ethnography’ lab, that deals with all of these areas and more, including cutting edge digital techniques. And here you will find a ‘learning pack’ (for both teachers and students) focused on the variety of ways illustration can be used by anthropologists.

This visual and audio material has often played a supplementary role in the final written work. However, some anthropologists aim to make the visual and/or the aural the centre of their project at all stages of their research – from creative means of data collection, to artistic work in research dissemination – recognising that vision and sound contribute different types of cultural understandings altogether. For this reason, visual anthropology and sounded anthropology are acknowledged as their own sub-disciplines. Visual and sounded ethnographies, in the forms of films, soundscapes, musical performances, photos or art exhibitions, contribute richly to the field.

Movement is yet another way people share and create cultural meaning and can be overlooked when it comes to ethnographic research. By itself, or combined with visual and/or sound techniques, movement through dance and other forms of performance can also be part of ethnography.

Below we provide examples and links that further unpack imagery, sound and movement as vital ways to communicate our knowledge as anthropologists.

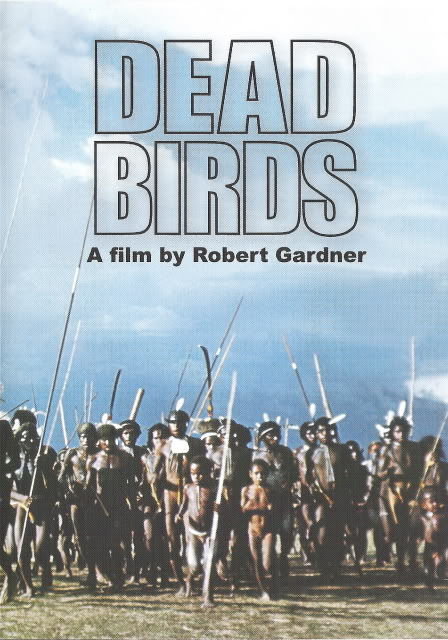

The poster for 'Dead Birds' (1963), a film about the Dani people of New Guinea, by visual anthropologist Robert Gardner.

There is debate, of course, about what makes an image or film 'ethnographic' (rather than just journalistic), and where the line between art and ethnography is. There is also debate about what makes something an 'authentic' representation of a particular people or place. The controversy about Shelby Lee Adams' photographs of often-stereotyped Appalachian ('hillbilly') people, taps into a lot of this debate, as per the linked article. There's no simple answer, but broadly speaking it is as much about the process and methods through which a visual text is arrived at, as it is about the final form.

This 3.5min video featuring Associate Professor Jennifer Biddle highlights visual anthropology's focus on innovative methodologies (often collaborative and applied) in the process of research. But visual ethnography doesn't always have to be high tech, and here you will find a 'learning pack' (for both teachers and students) focused on the variety of accessible ways illustration can be used by anthropologists.

Listening in. Installation by Pauline Fokkelman at Kadmium, Delft 2016. Image source: Simon Claessen (CC BY-SA), orginally posted to Flickr (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0).

An early example of an anthropologist interested in sound is Zora Neale Hurston. As heard in this 10min podcast (00:37 seconds in) about her work, Zora collected, sang and recorded folk-songs in the Southern US. Many of the audio recordings she made are available in the archives of the Library of Congress).

Like images, sound can capture things different to and beyond the written, in a potent way, that puts human experiences into specific social context. Not just composed music, but mundane sounds can do this. For example, the way this soundscape called 'women walking alone' (produced by an Otago undergraduate student) evokes feelings of fear or apprehension that have a specific social and historical context: specific gendered patterns of violence, and also in this case, to public and urban environments.

In this 40sec video clip, Katherine Dunham describes one of the motivations behind the 'Dunham Technique', and this short clip shows her performing with her company at the Cambridge Theatre, in London (1952). You can find out more about Katherine Dunham by exploring this timeline of her life.