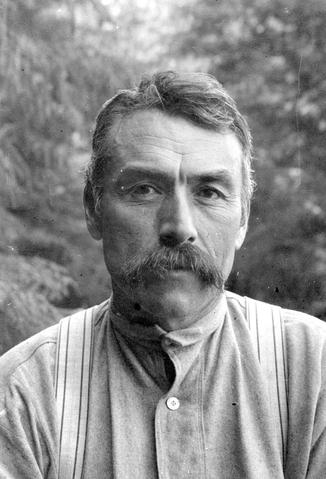

American anthropologist Franz Boas – posing for figure in USNM exhibit entitled – Hamats’a coming out of secret room – 1895 or before. National Anthropology Archives (NAA)

The roots of contemporary social anthropology are in the European Enlightenment. At that time there was a push for a systematic, scientific study of human beings. New theories of biological evolution influenced this quest in the 1800s, spilling into ideas of social evolution, which created a strong emphasis on describing and comparing people’s cultures via ‘ethnology’. (Note! Ethnology is not the same thing as ethnography).

Anthropological societies started popping up around the world in the late 1800s to support these interests. This was mostly an era of ‘armchair anthropology’ – with study and debate conducted by scholars in European and North American institutions, based on existing paper records, e.g. from explorers or missionaries.

Fieldwork-based anthropology

Traditions of anthropological fieldwork began in the early 1900s, with people like Bronislaw Malinowski and Franz Boas (consider the ‘forefathers’ of contemporary anthropology, and whose influence is discussed in this video) travelling to study different groups of people for months or years at a time, in order to learn about their lives and habits, and teaching their students to do the same.

American cultural anthropologist Margaret Mead, pictured in 1948. Source: Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Women such as Margaret Mead, Ruth Benedict, also conducted groundbreaking fieldwork and were prominent public voices in their time.

From these roots, two slightly different traditions of anthropology grew; in the UK the term ‘social anthropology’ prevailed, whereas the term ‘cultural anthropology’ was preferred in the USA. The first paragraph of this webpage gives an explanation of the slightly different focusses of each tradition. In New Zealand today both names are used, at different institutions, with very little difference in content or focus.

Schools of Thought

Some core ideas within social anthropology have persisted throughout its history, giving continuity to the field. For example, the technique of cross-cultural comparison, the approach of holism, and of cultural relativism. You can read about all of these in our Thinking section.

Over time, however, the discipline has also been shaped by a number of different schools of thought. Most were associated with one or more major influential scholars. We recommend this 5min MACAT video for an accessible ‘nutshell’ picture of how the ideas developed and progressed, one after another, to create the anthropology we know today.

If you want to go a little more in-depth, a few of the main schools of thought were:

Some schools of thought that influenced the discipline (including Social Evolutionism, which was an early influence that is not on the list) are now considered outdated, or even racist…

Decolonising the Discipline

‘Decolonising the campus’. Image of the removal of a statue of British Imperialist Cecil Rhodes, from a UCT (South Africa) campus, as a result of the controversial ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ protest movement in 2015. Source: Ntentema, Wikimedia.

Social anthropologists today do not believe the same things, or do their analysis the same way, as they did 100 or even 50 years ago.

Anthropology, as an academic discipline, has a problematic history tied up in colonialism (For a background on the history and ideology of colonialism, watch this 20min video).

During times of European colonial expansion, the work of anthropologists and ethnologists was often used to support colonial ideologies and projects. This drew on the highly ethnocentric theories of ‘cultural evolution’, also known as ‘social evolutionism’. We recognise many of these ideas today as false, and the part played by our discipline in these histories, as harmful.

Contemporary social anthropology is committed to ongoing reflection about the entanglement of our history with colonial science.

There have been movements both within and outside of anthropology, including by indigenous and non-white anthropologists, to critique and reshape the discipline (check out the history and work of the Association of Black Anthropologists, for instance).

George Hunt, a First Nations (Tlingit-English) man who consulted for Franz Boas. Today it is acknowledged that he was a linguist and ethnologist in his own right. Source: wikimedia.

This includes acknowledging that they had already been contributing to the field for a long time. In fact, many of the early (white) anthropologists drew on the expertise of indigenous “informants” and translators who actually ‘did’ anthropology on their behalf, but without the formal recognition or fame. For example George Hunt (1854-1933), pictured left, who worked with Franz Boas.

Another example is Mākereti Papakura (1873-1930) a renowned New Zealand tour guide who moved to England, where she gave lectures on Māori history and wrote her Masters thesis in anthropology at the University of Oxford.‘Mahi Tahi’, is a working group for promoting conversations about the relationship between Māori and anthropology in New Zealand, and sits within ASAA/NZ (the Association of Social Anthropologists of Aotearoa/New Zealand). They present an annotated bibliography about the history of Māori and anthropology.

Read more about the decolonising process within the discipline, as part of Thinking like a social anthropologist.

Specialisation and Sub-Fields

Many diverse people work as social anthropologists today, on many diverse topics.

Over time, some parts of the field have become more specialised, and distinct ‘sub-fields’ have developed, each with their own focus and techniques, journals and conferences (though still connected by an identification with the field and anthropology and its scope and values).

For example, Medical Anthropology (focusing on analysing experiences and practices around health and illness, including deconstructing biomedical systems), or Visual Anthropology (which focuses and recording and communicating data via visual and media technologies), and many more.