Culture

To think like an anthropologist, we need to make sense of the ultimate buzz-word in our discipline: ‘culture’. As this video explains, culture is a complex entanglement of both things (objects, people etc.) and ideas (norms, values, and symbols).

Influenced by different schools of thought, many anthropologists have tried to sum up ‘culture’ with a single definition. But, as this short introductory video suggests, it can be more helpful to understand culture through its qualities or characteristics. For instance, culture is dynamic and so our understanding of it is also constantly changing. In the past, some anthropologists viewed culture as somewhat ‘bounded’ – meaning tied to a particular place and time. Today, culture is widely understood as being shaped and shared on both a local and global scale.

It is useful to note that anthropologists look at both ‘culture’ and ‘society’ – but they are not the same thing. Where ‘culture’ is a system of shared meaning, ‘society’ refers to a group of humans, organised into particular forms of patterned social relations. So a society can have many cultures within it, and cultures can also be spread across more than one society.

When we write about culture in the contemporary world, we are often writing about subcultures or sometimes even countercultures embedded within more prevalent or dominant cultures (something this 10min video explores in more depth). Ultimately, most places, or groups of people, are shaped by more than one culture; we live in a world of plurality.

Holism

Holism has been a persistent lens through which anthropologists view culture. Holism means seeing culture as an all-encompassing system of meanings – something that links together how we think, feel, and behave, forming a particular way of life.

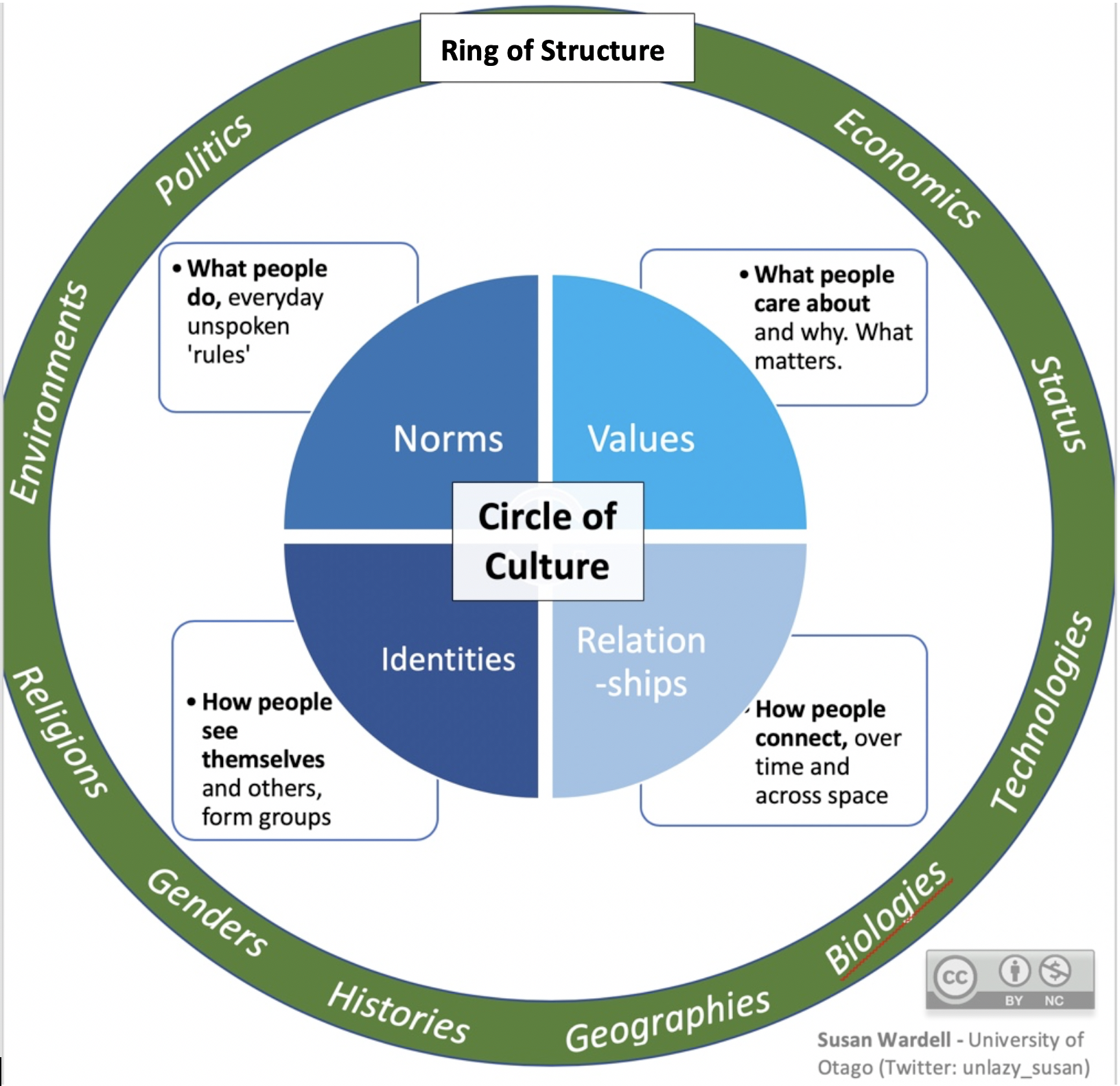

As this image shows, this allows us to conceptualise culture as a kind of glue connecting various arenas of life, or social institutions, together. (The word ‘institutions’ comes up a lot in the social sciences – here’s a 4min video reminder of what they are).

Some of the many things a macro perspective takes into account. Image: Ring of Structure. Created by Susan Wardell, University of Otago.

In order to gain this holistic view of how culture works, anthropologists like to zoom in and out between a micro (small, deep insights) and macro (more general) level of analysis. This allows us to see how local/individual thoughts, feelings or behaviours (micro), can be linked to larger, global, or societal processes and structures (macro) that we might not immediately think of as relevant – as this circle diagram (to the left) shows.

Professor Arjun Appadurai. Image source: TheSilentPhotographer

A segment of this video (up to 4:05min) on ‘paradigms’ – from a sociology perspective, but also applying to social anthropology – gives a great summary of the difference between micro and macro forms of analysis.

An example of an anthropologist considering both the micro and the macro is Professor Arjun Appadurai – a contemporary Indian-American anthropologist. In this 4.5 min video, he considers the paradoxes in how people think and feel about borders – in relation to politics, nation-states, and also global capitalist economies.

Emic/Etic

Emic and etic are terms used to describe two different angles or perspectives from which to understand something. Generally, emic refers to the ‘insider perspective’ – trying to make sense of something from the point of view of the people or groups you are engaging with – whereas etic refers to the ‘outsider perspective’ – a more analytic approach, or taking a step back to consider how other sources of knowledge (e.g. literature, theory) might make sense of a practice or situation. This web page expands a bit on this.

The emic/etic split, is related somewhat to the positionality of the researcher, too. We discuss that more in the ‘Researching like an anthropologist’ section. For both emic/etic, and insider/outsider, it is important to remember that the distinction is not always clear-cut; sometimes we can partially hold both perspectives at the same time.

Being aware of what perspective we are thinking from, forms one part of ‘reflexive practice’ (see our section on this further below), and this video gives a great example of someone engaging in this kind of reflexivity, discussing his experiences as part of a health research team in India, in relation to what ‘local’ (or emic) knowledge actually means.

Social Constructionism

Social constructionism is a paradigm (an established way of thinking or analysing) that helps us explain why and how people live, or societies run, a certain way. In other words, it is something social anthropologists like to use when we put on our ‘etic’ glasses, or practice looking at a cultural phenomenon from a ‘macro perspective’.

As this short video explains, social constructionism suggests that people’s individual and collective behaviour is guided by what people understand to be real and meaningful. It implies that we are responsible for creating our social realities – even though we might not consciously realise it. Some things that we take for granted as ‘real’ or ‘true’ – such as ‘money’ or ‘nation-states’ – only exist because people, over a long period of time, have repeatedly agreed it exists; agreed that lines on a map, or a particular shaped piece of metal or plastic, have particular value or meaning.

As this video adds, when something is “socially constructed” it depends on, and helps re-create, certain patterns of human interactions and relationships. And as the video emphasises, claiming something to be ‘socially constructed’ in no way suggests it isn’t real, or valuable, or important. And it doesn’t completely deny the existence of ‘reality’. Rather, it reminds us why such diverse ways of doing basic things (like eating, or praying, or being ‘respectful’) exist, and why things change over time even in a single place. It also reminds us that social change is possible.

Defamiliarisation

Learning to recognize how culture influences our lives is difficult because we are immersed in it from the moment we are born; it’s like asking a fish to realise it lives in water. Social anthropologists, however, have a tool to help them with this: defamiliarisation.

Anthropologists have stereotypically gone to study ‘other’ peoples and cultures. But becoming aware of our own culture (and culture as something everyone has) is just as crucial.

You may have heard a maxim of anthropologists: “Making the strange familiar, and the familiar strange”. Defamiliarisation helps with the second part. It means learning to pay attention to the things we usually take for granted – our own group norms, values, behaviours and identities. This is an especially difficult task for those of us who may have grown up as part of the dominant, or majority culture of a particular country or place. (See our section below on ‘Critical Thinking’ for more on this topic).

A good way to do this is by imagining your own culture from an alien’s perspective, as illustrated in this recent, popular web comic series, Strange Planet – another great example of defamiliarisation. The humour comes from finding different ways to describe everyday human things… from birthdays to sun-tanning. It makes you think about them in a new way. This cartoon plays with a similar idea.

A classic text given to first-year students to help understand defamiliarisation is Body Ritual among the Nacirema by American anthropologist Horace Miner, written in 1956. Have a read and see if the group of people he describes sound exotic and strange to you. Then see if you can work out what the ‘twist’ is, and who he is actually describing!

Practicing defamiliarisation helps us to recognise that there is more than one way of living and being. Understanding this helps us avoid being ‘ethnocentric’ and we become better at practicing ‘cultural relativism’ – concepts we define below.

Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism

To think like an anthropologist, we need to avoid ethnocentrism, especially as we practice comparison. Being ‘ethnocentric’ means viewing and judging all other cultures from the perspective that your own is the most important, correct, or superior one – as captured in this cartoon. It’s kind of like the criticism, “you think the whole world revolves around you”, but on a cultural level. Even just the assumption that your normal is the normal, is a way of thinking shaped by ethnocentrism (something this cartoon cleverly depicts).

This image (intended to be funny but with a serious basis) takes aim at the USA for having an ethnocentric view of the world. The dangers of ethnocentrism are misinterpretation, lack of understanding, and ‘othering’ – it can often lead to racial/ethnic prejudice, on an individual level, a social level, or even in political policy.

Again, we want to point out that it’s not just about individuals being ‘ethnocentric’, but whole institutions (including academia itself) being focused on a set of ideas and values that is taken for granted as normal, or superior – and weighing up all people, ideas, and processes, against that. The term ‘eurocentric’ applies here; and is probably the most common type of ethnocentrism.

The opposite of ethnocentrism, and a lens anthropologists promote, is called cultural relativism. This means trying to understand other people’s lives, norms, values, and behaviours in relation to their social, historical and cultural contexts (rather than in relation to yours). This links back to the idea of ‘holism’ – and for further examples of these two terms, we suggest this video.

It’s probably useful to note that we aren’t saying that you have to agree with or feel comfortable with all the different cultural practices you come across. Cultural relativism is not the same as ‘moral relativism’ (which says there is no absolute right or wrong). Many anthropologists do have their own strong moral, religious, or political beliefs, as well as their own ways of living that they feel attached to, and that is absolutely okay. But cultural relativism is a useful lens for reminding us to approach the people and things we study with humility, with close attention to their unique contexts – to stay open-minded to learn rather than filtering everything through our own assumptions.

Decolonising Ourselves

Colonisation has an ongoing impact in today’s world. This is addressed by areas of study such as ‘postcolonial theory’. From this perspective, this 17min video summarises some of the continual (cultural and academic) impacts of colonisation.

A protest sign at Ihumātao (a site of indigenous activism in New Zealand, in the face of land development, 2019). Photo: Alika Wells (source: wikimedia commons).

While we have begun the work of decolonising the field of social anthropology (as discussed in our history section), it is vitally important that anthropologists continually work at this. This includes (but is certainly not limited to):

- Unpacking the ways in which colonialism has shaped past academic theories and research methodologies, as well as the wider institutions anthropologists are tied to e.g. the tertiary education system.

- Thinking critically about representation in our own educational journeys, asking questions like ‘does my literature review include the work of indigenous scholars?’

In Aotearoa New Zealand, a key first step towards decolonisation is learning about te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi and how it has shaped, and continues to shape, the cultural politics of this country. This comic is a great resource for understanding the history of the Treaty – download it and have a read!

Some more useful resources:

- Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. This is an important book by Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith. She is widely recognized for shaping the discourse of decolonisation of academia in New Zealand and abroad.

- This “documentary“, called Babakiueria, turns the tables on the colonial history of Australia and the problematic representation of the ‘native’ population by many earlier ethnographic films.

- This website: RE: Discovering Aotearoa, has a wonderful collection of articles, illustrations and short documentaries revealing some ongoing impacts of colonisation in New Zealand, and how people are working to decolonise their identities.

Many anthropologists today are undertaking work that radically challenges colonial ideas… as well as other systems of inequality, or practices of ‘othering’. These are projects our values support, and our methods work well towards, especially if we are willing to also acknowledge and learn from our past as we do this.

Reflexive Practice

Social anthropologists are expected to think ‘reflexively’… but what does this actually mean? Being ‘reflexive’ means paying attention to the way knowledge is not just ‘gathered’, but constructed. It means unpacking the different contexts and influences behind academic work; the different forms of power and positionality (especially that of the researcher themselves) that shape that knowledge we produce as social anthropologists.

One way to practice reflexivity is becoming aware of our ‘selves’ as researchers, and remembering that we are all shaped by culture; our upbringing, socialization, experiences, and the norms and values of groups we have grown up within.

When we conduct research in any form, who we are (our personality, our beliefs, values, knowledge, morals) and our position in our social worlds (our identities) will impact the way we interpret different people and places. This is not a bad thing, so long as we pause to notice it, since sometimes, as this short video points out, we are not aware of how our personal biases shape our thinking and interactions with others. A commitment to reflexivity is about constantly asking questions about ourselves, as well as the people we are learning about, researching with, or writing on. This is covered, with a focus on research, in our section on positionality, which also mentions the ‘insider/outsider’ quandary.

Critical Thinking

Part of reflexivity, and useful for decolonising as well, is critical thinking. In social anthropology and other disciplines, critical thinking is about developing a certain attention towards power relationships and how they shape human worlds.

When we talk about power, we don’t mean only physical force wielded against another person or group. We also include the less obvious ways in which a society might govern people’s actions, e.g. through social or cultural norms and expectations, or certain discourses – which are powerful systems of ideas, often linked to particular institutions. This can relate to all sorts of things, such as what a ‘successful life’ should look like, what ‘healthy bodies’ should look like, or what makes a ‘family’. Social anthropologist’s can use ‘discourse analysis’, among other tools, to make these taken-for-granted ideas visible. This video gives a short but insightful summary of what this is and what it can reveal about how ideas act to shape our worlds.

Even in places where multiple cultures are present (i.e. most places!), there is typically one ‘dominant’ culture or set of ideas, and one term that helps explain this is hegemony – a concept well explained in this video by humanities vlogger Tom Nicholas (2017). It helps us make sense of the wider political contexts people live their lives in. For example, in this 7 min video, Dr. Alpa Shah practices critical thinking when she unpacks assumptions behind ideas of ‘development’ and ‘equality’ linked to the global hegemony of capitalism – using an ethnographic lens to draw on specific examples of local lifeworlds among the Adavasi peoples in India.

It is also important to know where our own positionality places us within the cultural hegemony we identify – do we fit or agree with the prevalent norms in our society, or do we feel alienated by them? Do we find ourselves relating to a certain ‘counterculture’, or do we find ourselves at home with the wider ‘status quo’? If so, we might need to work hard to ‘defamiliarise’ ourselves from the norms we are used to, in order to see who benefits and who is disenfranchised from the way a particular society is ordered.