Less well known than the Hocken’s New Zealand and Pacific material are our collections relating to Antarctica. We recently catalogued a letter with interesting links to Victorian Antarctic exploration and one of history’s most famous palaeontologists. Robert McCormick (1800-1890) was a surgeon and naturalist serving in the British Navy. After recovering from yellow fever contracted in the West Indies he evidently decided that tropical climates did not suit him, obtaining postings to cooler climes when he could. In 1827 he travelled to the Arctic under William Edward Parry on the Hecla, studying the natural history of Spitsbergen. After unhappy spells in the West Indies and Brazil, and several years back in Britain, in 1839 he travelled to the Antarctic as naturalist and surgeon aboard the Terror, commanded by James Clark Ross. In 1852 he returned to the Arctic regions on the North Star, mapping part of the Wellington Channel. In 1884 McCormick’s two-volume autobiography appeared, bearing the impressive title Voyages of Discovery in the Arctic and Antarctic Seas, and Round the World; Being Personal Narratives of Attempts to Reach the North and South Poles; and of an Open-boat Expedition up the Wellington Channel in Search of Sir John Franklin and Her Majesty’s Ships ‘Erebus’ and ‘Terror,’ in Her Majesty’s Boat ‘Forlorn Hope,’ Under the Command of the Author.

Our copies of the two volumes of this book bear the inscription “To Sir Richard Owen K.C.B. F.R.S. &c &c &c With the Author’s kind regards & best wishes. Jany 29th 1884.” Owen (1804-1892) was one of the major figures of Victorian science, best known for his contributions to anatomy, his disagreements with Charles Darwin, and as founding director of England’s Natural History Museum. These books are part of Dr Hocken’s original collection and bear his signature, along with the pencil marks “2/12/6 2 vols 30/- net”, suggesting he obtained them from a book dealer some years after Owen’s death. The books include a few annotations by Owen and at the back of the second volume he notes the pages which include references to himself. In a section where McCormick describes a reindeer-shooting excursion, he marked the passage “Eleven deer altogether were killed by the party, four of them shot by myself” and noted “what did you do with ‘em?”

|

| Title page of McCormick’s book, along with his portrait in naval uniform |

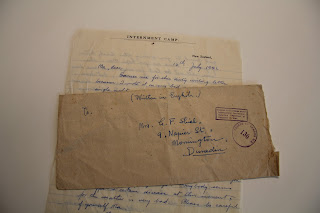

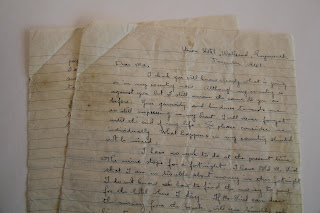

We recently came across a stray letter from McCormick to Owen dated 14 January 1884, which seems likely to have come into Hocken’s collection together with McCormick’s book. McCormick thanks Owen for his “kind & friendly letter” with “its good wishes, for the success of my book.” He asks if Owen would “permit me, to wind up my book with it as the last addenda to this record of my life”. McCormick had presumably left it far too late to add more to his book: Owen’s copy he signed just two weeks later. The appendix does include, however, an 1865 letter from Owen to General Sabine, President of the Royal Society, testifying to McCormick’s ability as a naval surgeon and naturalist.

|

| McCormick’s letter to Owen [Misc-MS-2133]. |

Blog post prepared by Ali Clarke, Reference Assistant