The NZ Government’s Action Plan to realise the Smokefree 2025 goal has signalled a more important role for social marketing. Social marketing can facilitate and reinforce population-level behaviour change introduced by new policies, thus modifying social norms, which also support long-term improvements in health outcomes. In this blog, we consider the role of social marketing in supporting the Smokefree 2025 goal and review strategies the Government could implement.

Social marketing has several important roles. First, it may deter people from unhealthy behaviours, such as smoking, by promoting alternative new behaviours; as these become established, they embed new social norms. Second, it may sway opinion by exposing industry practices, such as how tobacco companies deceived and then blamed people who smoke for the harms they experienced; this reframing may increase support for policy measures. Third, in line with the Ottawa Charter on Health Promotion, social marketing may help build supportive environments that support behaviour change.1 2 Fourth, social marketing can create opportunities to work more effectively with communities affected by unhealthy products. (For a more detailed background on social marketing – please see the Appendix.)

However, despite social marketing’s potential contribution to public health outcomes, NZ’s expenditure on smokefree social marketing actually declined following the Smokefree 2025 goal’s announcement;3 the plan’s proposal to increase investment in this area is thus very welcome.

Supporting and reinforcing behaviour change

Many social marketing campaigns aim to encourage compliance with policy changes by fostering understanding of the changes; for example, the current smokefree cars campaign “Drive Smokefree for Tamariki” was launched ahead of a law change that will occur later in the year. The campaign promotes understanding of the health risk that smoking in cars poses to others and uses this knowledge to challenge beliefs about hazardous behaviours. This campaign directly questions the belief that rolling down car windows will lower smoke concentrations to a point where they do not pose health risks to children. Knowledge about the harms of second hand smoke also questions attitudes that condone smoking in cars (e.g. “I don’t do it often, so it can’t be too bad”), thus enabling communication of an alternative action: staying smokefree in cars. As well as presenting an alternative, the campaign offers behavioural tips, such as putting cigarettes out of sight or focussing on alternative stimuli, such as music. The campaign thus supports behaviour change by showing how it might occur.

The Drive Smokefree for Tamariki campaign website provides information about the very high support for the law change and uses prevailing social norms to reinforce the new smokefree cars policy. Social norms evolve over time and can reframe an industry or behaviour so that what was once accepted behaviour moves outside normal social practices and interactions.

The US Tips from former smokers® campaign also offers constructive advice to people who smoke, though with a difference. People who have suffered serious harms from smoking offer advice to other smokers, including suggestions about how to manage shaving around a stoma (a small hole in someone’s throat that allows breathing) or wearing prostheses that replace limbs lost to peripheral vascular disease.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

In summary, these campaigns recognise that individual dispositions (e.g. expectations about smoking) and interactions with environments (e.g. role modelling and social norms) will shape smoking practices.

Reframing the acceptability of smoking

Unlike the US, where the Truth campaign exposed the harm caused by tobacco companies,4 created a social movement of young people who reject tobacco,5 and greatly reduced smoking uptake among youth non-smokers,6 NZ has been slow to adopt explicit industry denormalisation campaigns. Rather than expose tobacco companies as organisations that have specialised in corporate deceit, government-funded NZ campaigns have used softer approaches. For example, Stop Before You Start presented smoking as an unwanted friend in an unhealthy relationship, whereas the US Real Cost campaign used confronting imagery to present an industrial epidemic spanning multiple products and exacting a high physical, social and economic price.

campaign exposed the harm caused by tobacco companies,4 created a social movement of young people who reject tobacco,5 and greatly reduced smoking uptake among youth non-smokers,6 NZ has been slow to adopt explicit industry denormalisation campaigns. Rather than expose tobacco companies as organisations that have specialised in corporate deceit, government-funded NZ campaigns have used softer approaches. For example, Stop Before You Start presented smoking as an unwanted friend in an unhealthy relationship, whereas the US Real Cost campaign used confronting imagery to present an industrial epidemic spanning multiple products and exacting a high physical, social and economic price.

To date, the only NZ campaigns taking a strong denormalisation approach were led by Te Reo Marama (e.g. Māori Killers, see example). People from affected populations led and mobilised these campaigns, which added to message credibility and authenticity.

Source: Google Images, used with permission from Shane Kawenata Bradbrook, former director of Te Reo Marama

Arguments against NZ adopting a comprehensive denormalisation approach, similar to the Truth campaign, have noted the challenges of ‘importing’ overseas ideas without first engaging with affected populations, the sustained investment required, and the NZ tobacco industry’s media profile, which is lower than that of major US tobacco companies. Yet, recent evidence suggests the tobacco industry uses both overt and covert approaches to influence policy making;7 8 allowing these companies to operate in obscurity reduces their public accountability and may slow policy progress, and suggests NZ should reconsider whether industry-focussed campaigns could support the Action Plan.

campaign, have noted the challenges of ‘importing’ overseas ideas without first engaging with affected populations, the sustained investment required, and the NZ tobacco industry’s media profile, which is lower than that of major US tobacco companies. Yet, recent evidence suggests the tobacco industry uses both overt and covert approaches to influence policy making;7 8 allowing these companies to operate in obscurity reduces their public accountability and may slow policy progress, and suggests NZ should reconsider whether industry-focussed campaigns could support the Action Plan.

Smokefree: Creating new role models and norms

As well as illustrating how tobacco companies’ actions fall outside social norms (and breach legal obligations),9 social marketing can also reinforce behaviour by presenting it as normative or practised by role models.10 This approach assumes that communicating what others do may prompt and reinforce desirable behaviour, such as quitting and remaining smokefree.

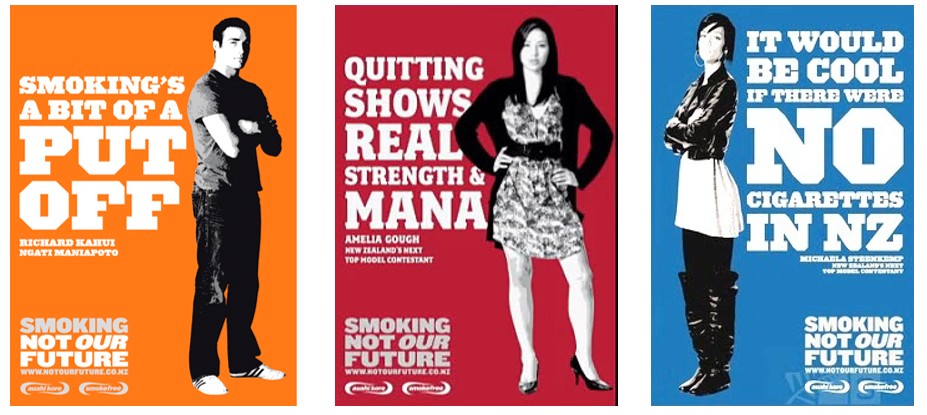

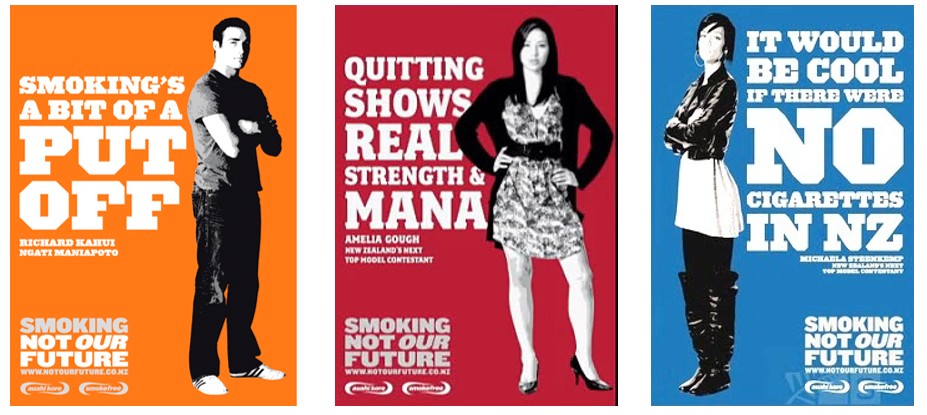

The Smoking: Not OUR Future campaign, developed by the former Health Sponsorship Council, is arguably the most powerful social norms campaign run in NZ (see campaign images below). This campaign used quotes from youth role models to highlight the social cost of smoking. The examples below reframe smoking and suggest it reduces young people’s social standing. Instead of providing connections with others, smoking is a “put off”; rather than demonstrate rebellion or other socially valued attributes, it is quitting, not smoking, that brings mana, and rather than being an accepted practice, the speakers look forward to a country without smoking.

Source: Google Images, various sites

Effectiveness of social marketing

Social marketing campaigns designed to prevent smoking among young people and encourage quitting among established smokers can be highly effective. Young people who had high exposure to the US Real Cost advertisements were less likely to report having smoked relative to young people who had lower exposure to the campaign,11 12 and researchers have estimated that campaign exposure was associated with several hundred thousand US young people not starting smoking.11 12 Earlier US campaigns, such as the Truth campaign, have achieved similar results,6 13 Further, economic analyses found both the Tips from former smokers and Truth

campaign, have achieved similar results,6 13 Further, economic analyses found both the Tips from former smokers and Truth campaigns were highly cost-effective and successful.1415

campaigns were highly cost-effective and successful.1415

Evaluations of NZ smokefree campaigns also show their impact and suggest approaches that could be used successfully in the future, for example, a “by Māori, for Māori” campaign.1617 NZ studies also show well planned, evidence-based and theory driven campaigns bring cost-savings to the health system,18 particularly when integrated with other strategies, such promoting calls to the Quitline.19 There is also international evidence that social marketing campaigns may reduce the risk of relapse.20 Nonetheless, social marketing is not a panacea and campaign effectiveness will depend on the nature and complexity of the behaviours in question, the campaign execution, and exposure among priority populations. Careful planning is required to avoid concerns that social marketing may privilege population groups with greater access to resources while disadvantaging priority groups (e.g. Māori or Pacific) that may have fewer resources and less support.

Using social marketing to support the Smokefree 2025 goal

Social marketing’s role in helping achieve the Smokefree 2025 goal will depend on the strategies included in the final Action Plan. We suggest key roles should include communicating core policy measures and building support for these, countering potential tobacco industry activity, and reducing any unintended impacts of these measures. For example, if the Action Plan introduces very low nicotine cigarettes (VLNCs; discussed in an earlier blog), a social marketing campaign could achieve several objectives. First, it could increase knowledge by explaining how VLNCs will support switching to other nicotine sources, such as NRT (e.g. patches or gum) or vaping products, or to quit nicotine use altogether. Second, an integrated campaign could intensify quitting support from health workers, ensure alternative products were accessible from expert retailers who could assist switching, and provide on-going support to assist people to quit nicotine use when they felt confident they would not relapse to smoking. Finally, a social marketing campaign could clarify that, although nicotine causes addiction, the major harms of smoking come from inhaling smoke, thus addressing misperceptions that may impede use of alternative products.

The successful campaigns we have described above require a strategic and integrated approach; campaigns must follow best practice guidelines, particularly with respect to campaign reach, frequency and duration, if they are to have a strong impact.21 22 They must also reflect the needs, priorities and voices of core communities, particularly Māori, whose leaders first proposed a Smokefree Goal in 2010 and highlighted the urgent need to eliminate smoking disparities. The Action Plan will also need to address potential risks; for example, disinvestment in the tobacco control sector means implementing well-planned, comprehensive social marketing campaigns may be challenging. Nonetheless, the Action Plan’s focus on strengthening Māori governance and equity, and recent government announcements regarding a Public Health Agency and Māori Health Authority suggest we may soon have an infrastructure that can address these challenges. We look forward to the final Action Plan outlining a comprehensive approach using social marketing to explain new policy measures and strengthen smokefree norms.

*Author details: JH is a Professor of Public Health she was formerly a Professor of Marketing and developed NZ’s first university courses on Social Marketing. AW, NW, PG, GT and RE are all members of the Department of Public Health, University of Otago Wellington. LR is a member of the Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, University of Otago, Dunedin. All authors are members of the ASPIRE 2025 Centre.

APPENDIX: Social marketing: A brief background

In the early 1950s, when marketers realised how effectively radio and television advertising could sell their products, Weibe, a research psychologist asked: “Why can’t you sell brotherhood and rational thinking like you sell soap?” (p679).23 He concluded that marketing could support social goals and suggested the more a social campaign drew on commercial marketing practices, the greater its chances of success.23 Two decades later, marketing academics responded to Weibe’s question and proposed the term “social marketing” to describe how integrated marketing strategies used to prompt purchase behaviours could also address social problems.24

Yet, despite the success of commercial marketing, early writers noted that social change was more complex than encouraging consumers to add a new brand of soap powder to their purchase repertoire.25 They cautioned that social marketing would not be a panacea to challenging social problems, which often involved entrenched behaviours that had developed in response to economic and social environments.

Early recognition that social marketing was not simply a matter of individual behaviour change, but required environmental change, acknowledged the need for robust public policy to support long-term, sustainable behaviour change.2 This environmental orientation also prompted a stronger focus on commercial practices, which continue to define purchase and usage settings. Critical social marketing studies have analysed the many health problems caused by tobacco, alcohol, and junk food marketing, and noted how dominant commercial voices undermine health promotion initiatives and create confusion among consumers.26 27 These analyses have revealed how corporations, drawing at times on devious and misleading approaches,28 oppose evidence-based policies that would constrain their marketing and thus their profits.1 7

Nevertheless, social marketing can fulfil several important roles in combatting the problems caused by commercial marketing. First, it may promote alternatives to the high-risk behaviours put forward by corporations, such as tobacco, alcohol and junk food companies, and help establish and embed new behaviours. Second, it can expose industry practices, particularly how some corporations deceive and then blame consumers. Third, it can foster environments that question industry discourse, challenge corporations’ dominance, and provide more supportive contexts for behaviour change.1 2

campaign

campaign