In the depths of winter, most people from southern New Zealand head to warmer climes for a much-needed dose of Vitamin D. Yet during the height of the last Ice Age, one species of moa did just the opposite.

I’m reminded of Bill Bailey’s En Route to Normal tour that visited Dunedin last year where he was performing one of his great comedic songs. On this night he was singing about being at a dark deserted crossroads, framed by a lone street light, with only a kiwi for company. The punchline, delivered to peels of laughter from the audience, is that it was a Friday night in Invercargill. This comically disparaged city is New Zealand’s southernmost, just a few hours down the road from here, and the butt of many local jokes. I strongly suspect Bill’s song was about Dunedin when performing for his Invercargill fans.

I’d like to think that during the height of the last Ice Age 29,000 to 19,000 years ago that southern Te Waipounamu South Island was a little more lively as a refugial ‘utopia’. Small pockets of forest and the animals that depended on it, including the extinct eastern moa (Emeus crassus), could ride out the Ice Age and bide their time until the great avian ‘OE’ (for international readers, the overseas experience is a kiwi right of passage) to reclaim parts of their former range. But how did we get here?

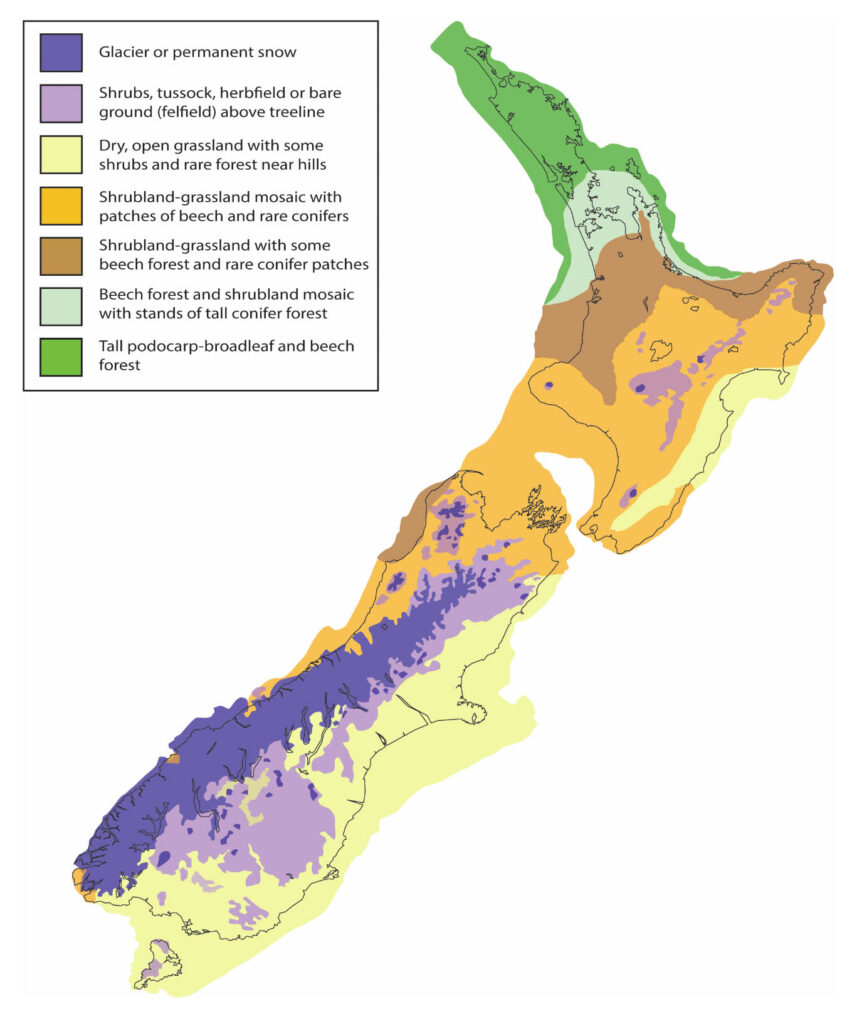

New Zealand during the Ice Age was an alien world. Sea levels dropped 120 metres. You could walk from one end of the country to the other without needing to take the Interisland Ferry. Much of the South Island was under an ice cap with glacial fingers reaching to the sea. What wasn’t covered by ice was cold and windy alpine tundra. It was thought that most forests had retreated to northern areas of both main islands, but recent genetic research has suggested that small pockets of forest survived in situ in small refugia in southern areas.

There is a rich fossil and archaeological record in New Zealand, full of the ghostly bones of moa. Some are so well preserved it’s like they died only yesterday, reaching across hundreds of years to tell their story. Radiocarbon dating can place moa bones in time, while ancient DNA can tease out their genetic whakapapa. This has allowed us to determine where different moa were in Aotearoa, and how this changed, over thousands of years.

The feathered chonk of our tale is the eastern moa. Up to 80 kg, this short-legged and stocky moa was common throughout eastern and southern Te Wai Pounamu during the Holocene, the warm interglacial period we’ve found ourselves in for the past 11,600 years. Females ruled eastern moa society, being 15-20% larger than males, which I suspect resulted in some fairly one-sided arguments, while males had long windpipes allowing them to make loud and resonant calls on the pre-human New Zealand dancefloor.

Eastern moa preferred lowland and wetland forest environments, whether that was sand dunes on isolated rugged beaches, grassland-shrubland mosaics, or the forests that covered the eastern and southern South Island at the time of human arrival. Their preserved gizzards (stomach contents) in swamps, and coprolites (desiccated faeces) in dry rock shelters, have backed this up.

While eastern moa were widespread throughout the warm Holocene, they were in tune with their environment. Going further back in time towards the height of the last Ice Age, they followed their preferred habitat and retreated to that exclusive enclave in southern New Zealand for around 10,000 years of Friday nights.

But what effect did this staged retreat into a small refugium, compared to their usual large patch of real estate, have on levels of genetic variation? Did eastern moa retain high levels or did they lose it all in a population bottleneck to resemble levels found in most royal families? This is what interested my fantastic PhD student Alex Verry, now at the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse and the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, using palaeogenomics to assess extinction risk in birds from Mauritius and Réunion (cue jealousy).

Preliminary palaeogenetic data by Michael Bunce certainly suggested something drastic had happened in eastern moa. Analysis of small fragments of ancient mitochondrial DNA (passed down through the female line) indicated a large bottleneck had occurred, but we needed more evidence. Alex dove into lab work headfirst, bringing our lab into the palaeogenomics era, which is something I’ll be forever grateful to him for. Using a hybridisation-capture technique to fish for ancient eastern moa DNA, Alex sequenced complete mitochondrial genomes from across their range through space and time – a true population palaeogenomics approach.

It turns out that eastern moa did refuge in southern Te Waipounamu during the last Ice Age, and only expanded out after the climate warmed and the White Walkers had been pushed back behind the wall. While there was very little genetic diversity due to a seriously big bottleneck, this moa royal family showed more genetic diversity on their Ice Age estate compared to the countryside outside of it, indicative of post-glacial expansion. This matches what we see in the fossil record with the oldest post-expansion eastern moa found at Glencrieff in North Canterbury (11,000-14,000 years ago) and Albury Park in South Canterbury (7,000-9,000 years ago).

So why should we care? Rather than moa, in general, having one response to climate change to rule them all, it looks like every species was unique and wanted to be an individual. Heavy-footed moa (the Cartman of the moa world) contracted into northern and southern refugia, while the mountain goat of moa, the upland moa, sought refuge in four far-flung areas of the South Island. For these moa the Ice Age was a creative force for biodiversity, generating new genetic lineages, compared to the more traditional thinking from the northern hemisphere that glaciations are destructive forces as eastern moa experienced. The upshot is that responses to past, and arguably, more importantly, future climate change, shouldn’t be generalised across species. And that goes for evidence-based conservation management strategies too.

While eastern moa suffered greatly at the hands of Jack Frost, by the time Polynesians arrived in Aotearoa, they were very common and widespread despite their low levels of genetic diversity compared to other feathered chonks like heavy-footed and South Island giant moa. Overhunting, habitat destruction, and predation from introduced animals sharp in tooth and claw such as kiore and kurī led to the extinction of the moa, not the ghost of Ice Ages past.

Travel around southern New Zealand today, and to the uninitiated, you’ll pass through several small country towns like Owaka, Eastern Bush, Kauana, and Opio to name a few. But to us time-lord scientists, the names of these small towns tell a different story of ancient swamps and caves containing the skeletal ghosts of Aotearoa’s long-lost moa whose fascinating story has just had a few more exciting pages added to it.