CFP: Children & Young People in British Colonial Contexts

Dr. Hugh Morrison, with support from the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture, will be hosting a 2-day symposium on 24 & 25 August at the Hocken Collections on the histories and experiences of children and young people. The Call for Papers is below:

******

Unpicking the Tapestry: Children & Young People in British Colonial Contexts

Children and young people were ubiquitous and significant players on the stage of national and colonial formation, yet this remains a significant gap in the history and historiography of British world colonial societies like Aotearoa New Zealand. Therefore an exclusive focus on the historical place of children and young people in comparative colonial contexts is timely in terms of further development; both in the New Zealand context and that of the wider British world. Such discussion can inform a better historical understanding that is locally, nationally, and transnationally configured.

This symposium is sponsored by the Centre for Research on Colonial Culture at the University of Otago, New Zealand. It aims to bring together scholars (from New Zealand and beyond) who are interested in a range of aspects of colonial children and young people under the rubric of ‘unpicking the tapestry’. If colonialism is the overall tapestry holding together children’s and young people’s lives, then what is revealed when we begin picking away at the individual strands of this tapestry? In particular the symposium is interested in addressing a number of key questions which include: What does it mean to talk about ‘colonial childhoods or adolescence’ or to think about children and young people in relation to colonialism? What colonial sites were significant or influential for children’s and young people’s lives, and in what colonial sites were children influential? To what extent were children and young people constrained by boundaries or moved fluidly across boundaries (eg. gender, race or ethnicity, nation, class, religion), and to what effect? What are the sources for excavating and interpreting colonial childhoods? What are the gaps and silences? How do we negotiate these? In what ways might a comparative approach (across colonial societies) expand or limit our understanding of colonial childhoods and adolescence? What are the significant challenges and opportunities in this field of academic enquiry? These are some of the questions we wish to explore further over two days of keynote address, paper presentations and round-table discussions.

The keynote speaker will be Canadian historian Professor Kristine Alexander, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Child and Youth Studies at the University of Lethbridge, Alberta. She will be joined in round-table discussions by education historian Professor Helen May (College of Education, University of Otago) and one further person to be confirmed. Up to a further 16 paper presentations are anticipated in plenary session form (half hour sessions per paper).

Paper proposals should be sent by email to Dr Hugh Morrison (hugh.morrison@otago.ac.nz) in the form of a 300 word (maximum) abstract, accompanied by a paragraph giving academic or professional background by Tuesday 31 March, 2015. Accepted papers will be notified by Friday 24 April at the latest. There will be no registration/symposium costs for presenters, but travel and accommodation costs will need to be individually paid for. It is anticipated that symposium papers will be published as an edited book collection or special journal issue.

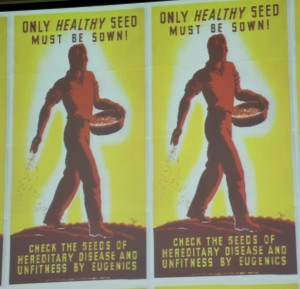

Eugenics in British Colonial Contexts

The Centre’s year has kicked off to a good start with “Eugenics in British Colonial Contexts: Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa” in the comfortable facilities of St Margaret’s College, on 7-8 February. This single-stream conference was organized by Associate Professor John Stenhouse (History, and CROCC) and Professor Hamish Spencer (Genetics, and Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology and Evolution), and Professor Emerita Diane Paul (University of Massachusetts Boston, Research Associate, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, and currently William Evans Fellow at Otago).

The Centre’s year has kicked off to a good start with “Eugenics in British Colonial Contexts: Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa” in the comfortable facilities of St Margaret’s College, on 7-8 February. This single-stream conference was organized by Associate Professor John Stenhouse (History, and CROCC) and Professor Hamish Spencer (Genetics, and Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology and Evolution), and Professor Emerita Diane Paul (University of Massachusetts Boston, Research Associate, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, and currently William Evans Fellow at Otago).

After the event was opened by PVC Humanities, Professor Brian Moloughney, Tony Ballantyne (Otago) spoke first on “Colonisation and the problem of Population”. Tony began with the question, when did the Eugenics begin in New Zealand, as its history has various possible beginning points. It was an issue that had significant discursive importance to the big questions of the day, in particular with regard to population, immigration, and political economy.

John Stenhouse (Otago) spoke on William Pember Reeves, the Liberal politician of the late nineteenth century. Reeves, celebrated for his Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration legislation, is less well known for his efforts to restrict the immigration of undesirables, including those deemed to be physically or mentally defective. Reeves was one step beyond public opinion, and his efforts stalled. A watered-down bill, principally anti-Asian, was more successful.

Sir Robert Stout, eminent New Zealand politician and jurist, was the focus of Emma Gattey’s (Otago) talk. A Freethinker and advocate of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, Stout’s interest in eugenics is less well known. An active member of the Eugenics Society, Stout pushed for the segregation of mental defectives from society. Even his own daughter, an epileptic, was held at Seacliff Lunatic Asylum for a number of years.

Stephen Garton (Sydney) talked on the illiberalism prevalent in early twentieth-century Australia, a time now seen when medicine particularly infected by ideology. Ultimately, however, liberal safeguards survive and all efforts at sterilization of mental defectives fail in Australia, and without a scientific consensus, politicians were reluctant to pass contentious legislation. Jane Carey (Wollongong) took a wide view of the issue of eugenics, arguing that race, class and gender are interlinked into eugenist discourses. Eugenics is often seen in terms of national historiography, but was a transnational discourse. Although for some it was about the “English race”, others took a different view, prepared for example, to “breed out colour” through intermarriage.

Click to enlarge. From left, Caroline Daley, John Stenhouse, Hamish Spencer, Stephen Garton, Angela Wanhalla, Jane Carey, Diane Paul, Barbara Brookes, Erika Dyck, Charlotte Macdonald, Susanne Klausen, Rosi Crane.

Baby contests began first in the US in 1854, but soon spread to other countries, including New Zealand. Caroline Daley (Auckland) discussed how initially these shows attracted considerable opposition, but they also appealed to those with proto-eugenic sentiments as indicators as to the quality of the racial stock. Shows took on a more scientific edge, with doctors weighing and measuring the babies. However, Caroline cautioned at reading too much into the eugenist angle, as consumerism was often a motivation for these events, and they continued to be held after eugenics declined in popularity.

Truby King is famous as a health reformer, both in terms of treatment of the mentally ill, and infants’ and children’s health, and as the founder of the Plunket Society that promoted his theory of mothercraft. Diane Paul (Massachusetts Boston) noted that more recently King (and the Plunket Society) have been labelled as eugenist. While it is possible to find some eugenist ideas in his writing, King was also critical of eugenics at times, believing that environmental factors, rather than hereditary, were more important, and how we classify King’s ideas really depends on how we define eugenics.

Susanne Klausen (Carleton) spoke first on the second day, looking at the impact of eugenist theories in South Africa that emerged in the late nineteenth century. One issue that troubled some in South Africa were the poor white Afrikaners, who migrated into the cities, living in slums together with black South Africans. Deemed as less intelligent than other whites, the Race Welfare Society tried to curb their high fertility rate. However, ultimately the eugenics movement in South Africa was relatively weak. In the face of large non-white populations, a white ethnic nationalism prevailed over biological imperatives, with poor white Afrikaners deemed salvageable in the interests of race unity.

Although eugenic discourses percolated through all of Canada, it was only in Western Canada that two provincial parliaments, in British Columbia and Alberta, passed laws legalizing sterilization of the mentally defective. Erika Dyck (Saskatchewan) discussed the situation in Alberta, where most of the sterilizations took place, between 1928-73. It was agrarian feminists who initially pushed for sterilization, but the legislation was strengthened by the Social Credit government, who removed informed consent. More recently it has been claimed that the government targeted indigenous women, but historical evidence for this is lacking, with indigenous health care, run by federal authorities, in general being provided at the most minimal levels.

Charlotte Macdonald (VUW) looked at the history of eugenic discourse in New Zealand. The high point of New Zealand eugenics was the Mental Defectives Amendment Act in 1928, which established a Eugenics Board. “Experts” could be powerful, for example Dr Theodore Gray, the Head of the Mental Hospitals Department, who recommended the sterilization of the mentally unfit, which became Clause 25 in the 1928 Bill. But this legislation was not palatable to all, and was watered down in its final form. Charlotte also looked at the Healthy Body Movement that appeared in a number of the “white” colonies in the 1930s. Although there is an assumption that this reflected eugenist ideas, this was not actually the case, although the perception may have led to its eventual demise.

Angela Wanhalla (Otago) discussed how marriage was also a concern in the discussion leading up to New Zealand’s 1928 legislation. The initial bill included Clause 21 that would have prohibited the marriage of the mentally or socially defective. While some newspapers were broadly supportive, the Anglican and Roman Catholic Churches opposed any state interference in the institution of marriage, and the Labour Party’s Peter Fraser led the fight against the worst aspects of the legislation in parliament. Eugenic discourse did influence divorce law, with insanity grounds to dissolve a marriage, although few used it due to the length of time required. New Zealand’s response was to segregate the mentally unfit rather than sterilization or marriage prohibition.

The last speaker, Hamish Spencer (Otago) also focused on the Mental Defectives legislation of 1928. The first Act, which distinguished between mental illness and defect, was passed in 1911. In 1924, a Committee of Inquiry convened to look into Mental Defectives and Sexual Offenders. A number of academics urged eugenic controls, such as the registration and sterilization of mentally defectives and immigration control, which the commission broadly agreed to. The 1928 legislation also came out of Dr Gray’s Report on Mental Deficiency, compiled after a world tour looking at how other countries dealt with the issue. As noted above, Peter Fraser was a vehement opponent of sterilization. Although the government had the support in parliament to pass this, it was not confident of wider public support and amended the original bill. But it was a very close thing.

All participants felt that this event was extremely productive. Despite differences in how each country applied eugenist ideas, the discourse was transnational. The organizers are now investigating publication options to get their research to a wider audience.